“You cannot ignore the past if you want to improve the present”

It’s a December afternoon at the Faculty of Letters of the University of Lisbon (FLUL). In a small room in the Library building, we meet Ioannis Petropoulos, minutes before the start of another class in the seminar he has been teaching this semester, every Monday, entitled ‘Saved by education: St Basil the Great’s “Address to the young on Hellenic education” and Background texts’.

Born in Greece, Ioannis taught ancient Greek literature at Oxford, where he graduated; he has worked at different Greek universities – in particular at the Democritus University of Thrace, where he was a professor for nearly three decades – and is Director Emeritus of the Centre for Hellenic Studies in Greece at Harvard. In his long career, he has also taught at universities in Brazil, China and the United Kingdom.

This year, he came to Lisbon for a season as part of the first edition of the Gulbenkian Visiting Professorships in the Humanities, and we wanted to find out a little about his experience.

Learning to read critically

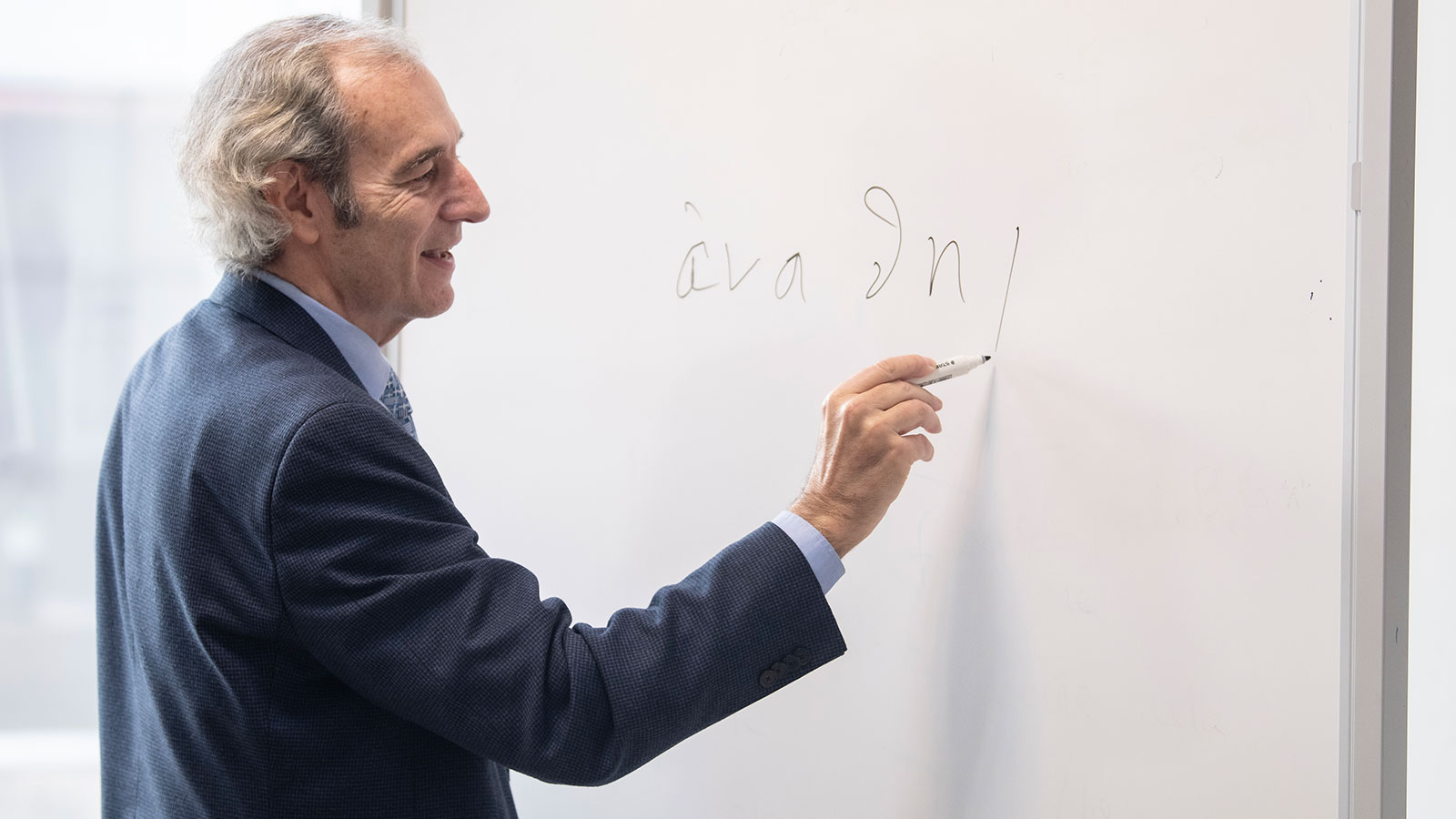

The seminar has 12 students enrolled, but this afternoon there are seven taking part in the class. The room is small and the atmosphere is intimate: the students, of different nationalities, sit around a table and everyone is friendly and complicit. The teacher speaks in English, but alternates with sentences in Portuguese (with a Brazilian accent) in moments of lightness and humour. For those watching, it feels like a conversation rather than a lecture.

The theme of the seminar, explains the professor, revolves around “a central text, which is almost a magna carta of humanistic studies”. It’s an address by St Basil of Caesarea, a Church father from the mid to late fourth century, who invites young people to read pagan authors with an open mind, on their own, and not let the Church or the State decide what they should read.

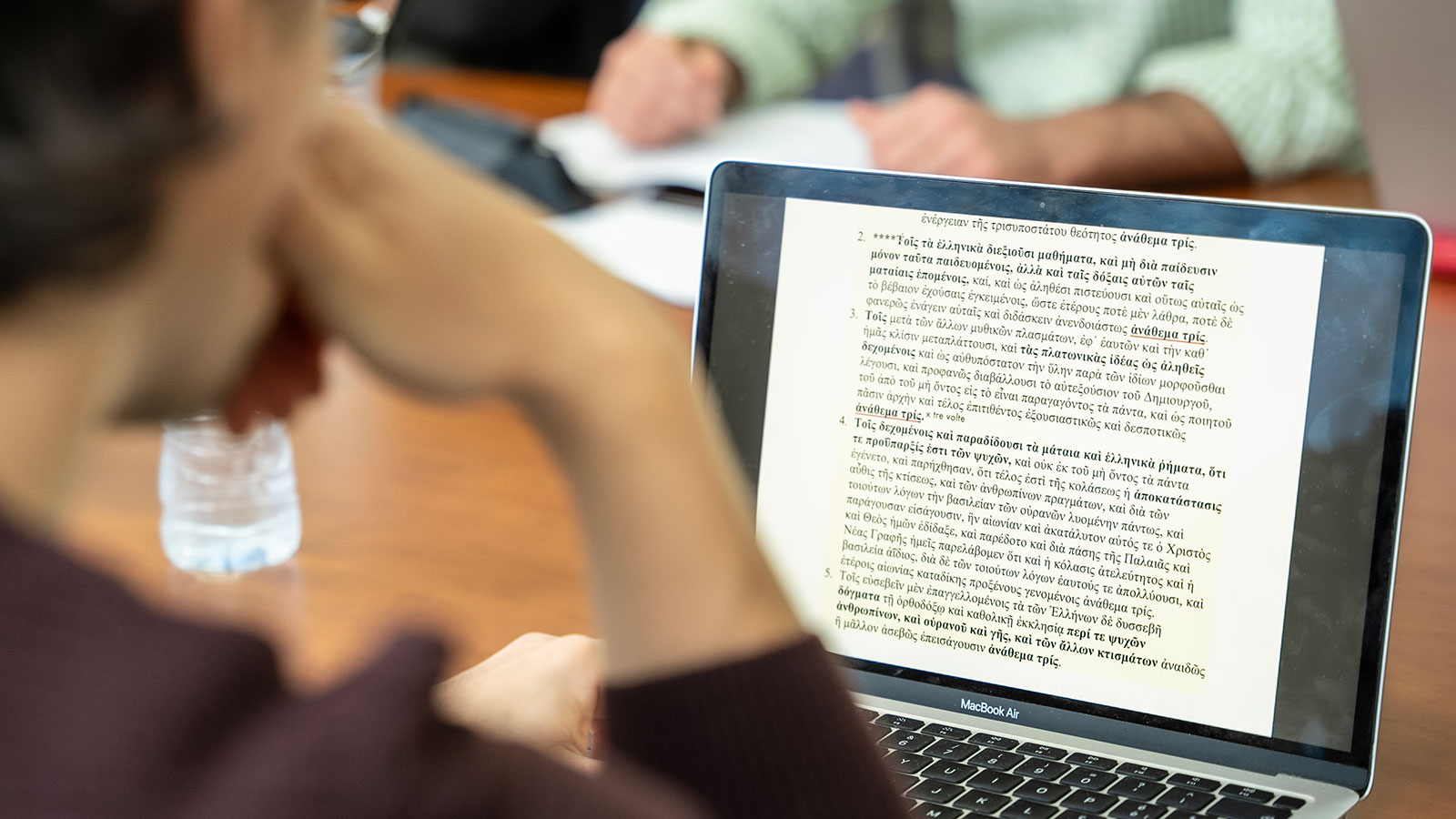

For the professor, close reading is the best teaching method. “You have to read carefully, read critically, read with suspicion. Nowadays we don’t do that, we zap across the internet and on the television and so forth.” And that is precisely what he brings to his classes at FLUL: teacher and students read the text literally, word for word, comparing the original Greek with the English translation, exploring all the references to other authors – Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch – “peeling back” the text in all its interpretations and ideas.

“You cannot ignore the past, if you want improve the present”, says the Greek professor with conviction. “We have to go back to ancient texts, texts before our time. You have to know grammar and syntax. And you always come away with a feeling of humility, you do.”

The importance of including ‘a bit of everything’

More than two hours of close reading of a text from the fourth century could sound tiring, but that’s not the opinion of Martim Cunha Rego, one of the students taking the course as part of the first year of his PhD in Classical Studies and the Study of Ancient Philosophy. “I’d even like to record the lessons, because he reads so well”, he explains.

Martim joined the seminar at the suggestion of another professor, as it is in line with his research topic: the history of ideas in antiquity. “It’s a very special subject, because we’re talking about a Christian author from the 4th century defending the study of non-Christian literature. And it’s largely because of this text that all the work of late antiquity has survived; because if there hadn’t been people like St Basil talking about the importance of preserving these ancient texts, they probably wouldn’t have been copied.”

On the other hand, he says, the professor is “an absolute gentleman “. “He knows so so so so much, and he’s an extremely intelligent and delicate person.” In his classes, they end up having “a little bit of everything”: “We have a lot of literature, a lot of syntax, rhetorical techniques, things like that… But then we also have a lot of philosophy and the history of ideas”. Not to mention Greek, which they had to learn to keep up with their studies. “That’s also another rewarding thing about this course: those who don’t know Greek are very welcome, but those who do can also benefit a lot from the work they’ve had to learn.”

A two-way process

Ioannis Petropoulos had already visited FLUL’s Centre for Classical Studies about ten years ago, on his own. “It was my first trip to Portugal, and I was impressed even then.” The Gulbenkian scholarship gave him the opportunity to do what he loves best: teach. “I wanted to put my personal project at the disposal of colleagues and students alike, and also take part in this sort of very enterprising atmosphere, open to intellectual history and new trends, while also being very seriously and traditionally interested in texts. It’s a perfect combination. I couldn’t refuse”.

In Lisbon, he found a group of interested and motivated students with an “admirable” command of Greek. “Many of the students are not even Hellenists, they’re Latinists; some are literature experts, others deal with philosophy. It’s an interdisciplinary group, so I’m quite favourably impressed.”

Despite finishing his semester of teaching in January, until the end of the academic year the professor will give four seminars open to the university, followed by a public conference, where he will summarise what he has been writing and studying in Lisbon: a commentary on this oratio by Saint Basil.

As for stopping teaching and retiring, that doesn’t seem to be in the emeritus professor’s plans. “As long as I’m operative and taking my vitamins, as my doctor told me, I’m going to be teaching.” He adds: “It’s not simply habit. Teaching feeds your research and your thinking, and vice versa, you see. Your research can be applied in teaching and make a difference to students. So it’s a two-way process, and I’m very happy and grateful to have this opportunity to do it at Lisbon University”.

The Gulbenkian Visiting Professorships in the Humanities are aimed at Portuguese Higher Education Institutions that wish to receive visiting professors from foreign universities with a scientific curriculum of high merit and with notable recognition in the area of the Humanities, with the aim of promoting new skills, fostering international cooperation of excellence and developing the national talent of researchers, teaching staff and students in this area.