Post-Pop. Beyond the commonplace

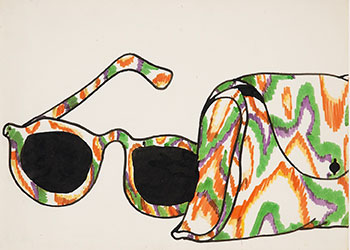

Curated by Ana Vasconcelos and Patrícia Rosas, this exhibition conveys the ways in which diverse Portuguese and British artists received, and in some form transcended, the lessons of Pop in moving on from the commonplace proposed by its language.

Fundamental names from the British artistic and cultural scene, such as Allen Jones, Patrick Caulfield, Jeremy Moon, Tom Phillips and Bernard Cohen feature in this exhibition where they are joined by works from their peers Teresa Magalhães, Ruy Leitão, Fátima Vaz, João Cutileiro, José de Guimarães, Eduardo Batarda, Menez, Nikias Skapinakis, Clara Menéres, among many others. There is a particular emphasis on the works from this period carried out by Teresa Magalhães that have hitherto remained practically unseen, as well as the equally unknown works by Ruy Leitão, who studied in London under Patrick Caulfield, who considered him one of this most brilliant students.

Also going on display are a considerable number of works from the Modern Collection of the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, some of which belong to the British art collection acquired in London between 1959 and 1965. The exhibition also draws upon works sourced from the Arts Council and British Council collections in London and among others deriving from institutional collections and those of private Portuguese collectors.

In interview, the two curators, Ana Vasconcelos (A.V.) and Patrícia Rosas (P.R.), set out various clues for interpreting this exhibition.

What are the main guidelines underlying this exhibition?

A.V. – We may talk about an innovative perspective on the collection connoted with Pop Art in the Modern Collection of the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, especially the important works of British art from the 1960s, calling into question their eminently pop affiliation. The same occurs as regards a significant set of works by Portuguese artists in this period. Bernard Cohen, one of the most important figures to the design of this exhibition, who is now today a highly valued artist – with twelve works on display in the permanent collection of the Tate –, defends that, at the time of the appearance of the pop language in London, in the mid-1950s, there were very interesting artistic works in production but with different aesthetic values.

There was an emphasis on creativity and all of this got suspended with the arrival of Pop Art. Cohen considered that Pop only appealed for a limited number of figurative themes and that it amounted to the first forced artistic movement at the international level and entirely controlled by the media. A rather radical position, perhaps, but that ensures we more clearly understand that not everything that did not fall within the Pop categories was lyrical abstraction or abstract expressionism, there were other equally interesting trends and announcing possible futures for artistic creativity.

Many of the artists connoted with Pop refused that affiliation, creating works conjugating abstraction and figuration, works with humour and a sense of the absurd, of nonsense, with great powers of communication. In sum, this exhibition questions the hegemony of Pop and its consequences for British art, extending this questioning very deeply into the Portuguese world.

How did Portuguese artists experience these twists and turns?

P.R. – There are two artists who take leading roles: Teresa Magalhães and Ruy Leitão who, along with Bernard Cohen, established the matrix for designing this exhibition. Both follow a pop prism as regards design and the aesthetic questions of the movement before then reaching beyond them in the ways that they show their objects or deploy other techniques, deviating them from their pop focus. Hence, alongside many other Portuguese artists, Teresa Magalhães adopts an attitude that contests the teaching of the Fine Arts in Portugal, which she accused of defending traditional values conditioning the creative freedoms of students. A large proportion of the works of the artist in the exhibition were produced in her atelier on the fringes of the School. As regards Ruy Leitão, son of the painter Menez, he lived in London from 1966 to 1970 and thereby experienced another social and artistic context.

A.V. – It is important to highlight that Ruy Leitão lived in London, was an international artist and never suffered from Portuguese isolationism. In turn, Teresa Magalhães did live in Portugal and produced some extraordinary works with a very strong sense of the epoch, adopting a pop vocabulary but with abstract and minimalist incursions that combined with cinema, music, fashion and photography. In 1973, the artist turned decisively towards the abstract expressionism of the post-war period that Cohen said, and in his own words, enabled a far greater level of creative freedom.

The boundary between Pop and post-Pop was not always easy to establish…

A.V. – This border is fairly tenuous. This exhibition seeks to show some of the derivations made by the many artists who, despite their connotation with Pop, moved away from its classical line and these deviations are both multiple and highly diversified. However, there is also much overlapping. If we flick through a classical Pop Art catalogue and view the works on exhibition, we understand the difference even while such is not always easy to explain. And this is a detail that pleases me; that our gaze knows more than that which we are easily able to define with clarity.

P.R. – This exhibition does in fact present a plurality of lines, embracing minimalist trends, for example, outside of the Pop universe. In this universewe can already distinguish a British Pop, more nostalgic, born of a European material and popular culture, in which collages and postcards stand out, from an American Pop, far colder, harsher, more communicative, more immediate. In the Portuguese case, the diversions from Pop emerge in works that contain a heavy political weighting or around themes such as the body or the eroticised body.

Is there thus uniqueness in the Portuguese case…

A.V. – This is a very interesting question to which Penelope Curtis (Gulbenkian Museum director) draws attention in the catalogue introduction, when affirming that there is an “Iberian Pop” which is undergoing recognition by the current history of art, just as there is a Pop particular to Eastern European countries that, just like the Portuguese case, was a means used against the regimes then in effect. The question is always the same: whenever having to get past the tight scrutiny of censorship, then there is always the need to say things in a different manner. There were many such caustic and critical works. In Portugal, with the April 1974 Revolution, there also came the chance to hear voices proclaiming social and political utopias.

P.R. – Many works on display reflect this experience; the most realist is the depiction made by Clara Menéres of a dead soldier, killed in the colonial war. Some artists spent time in Angola, such as José de Guimarães and António Palolo. Guimarães even held an exhibition in the Museum of Luanda, in 1968, with some of those works going on display here. Palolo received significant support in Angola from Guimarães and in his works the images with connotations of the ongoing war appear in a humoristic form, very colourful, as if a small puppet theatre. Eduardo Batarda did military service but did not end up serving in Africa; around this time, he went to the Royal College in London where he produced the sharpest and most compelling artistic criticism of the then prevailing Portuguese colonial situation.

Are there many otherwise unseen works included?

A.V. – Yes, beginning with Teresa Magalhães, by whom only two works from this period have previously gone on display. By Ruy Leitão, there is one painting that had never been seen before as it had remained in London ever since the years when he lived there. We also have hitherto unseen sculptures by João Cutileiro and works completed in Angola by José de Guimarães, which have never been exhibited before. There is also the display of four embroidered works by Clara Menéres, which, since they were first made and exhibited, have never since been seen. There is the return of works made in London by Ana Hatherly and by Sena da Silva, as well as rarely displayed paintings by Maria José Aguiar and Fátima Vaz. These are two artists with very interesting catalogues that fell into obscurity. The public also gets the opportunity to admire the works that featured the very first Paula Rego exhibition staged in Lisbon, at the National Society of Fine Arts in 1965. At this time, the artist had only sold two works, one of them – Manifesto (For a Lost Cause) – acquired by the Gulbenkian Foundation.

Beyond the works, is there any production detail you wish to highlight?

P.R. – I would like to draw attention to a particular curiosity in putting this exhibition together; actually, three curiosities. Along the extent of the visitor route, there are three large black boxes, a type of “thematic office”, which contain their own original graphic works and are three underground moments to this exhibition. These spaces, open to visit, are covered in works, posters, documents, music, archive images, etcetera. The first box is dedicated to fashion and music; the second to the eroticised body and new cinema; and the last approaches questions around national politics.

What do you hope the public takes away from this exhibition?

A.V. – We hope people enjoy what they are seeing. This is a colourful, visually very strong exhibition, with a great deal of diversity, that values the Portuguese art of this period. The exhibition presents things in a different fashion, practically proposing a type of flashback over these years (a revisiting to those who lived them), or another narrative for younger audiences. This relates to our recent past and the greater our knowledge about it, the greater the awareness we gain about the future.

See more about the event