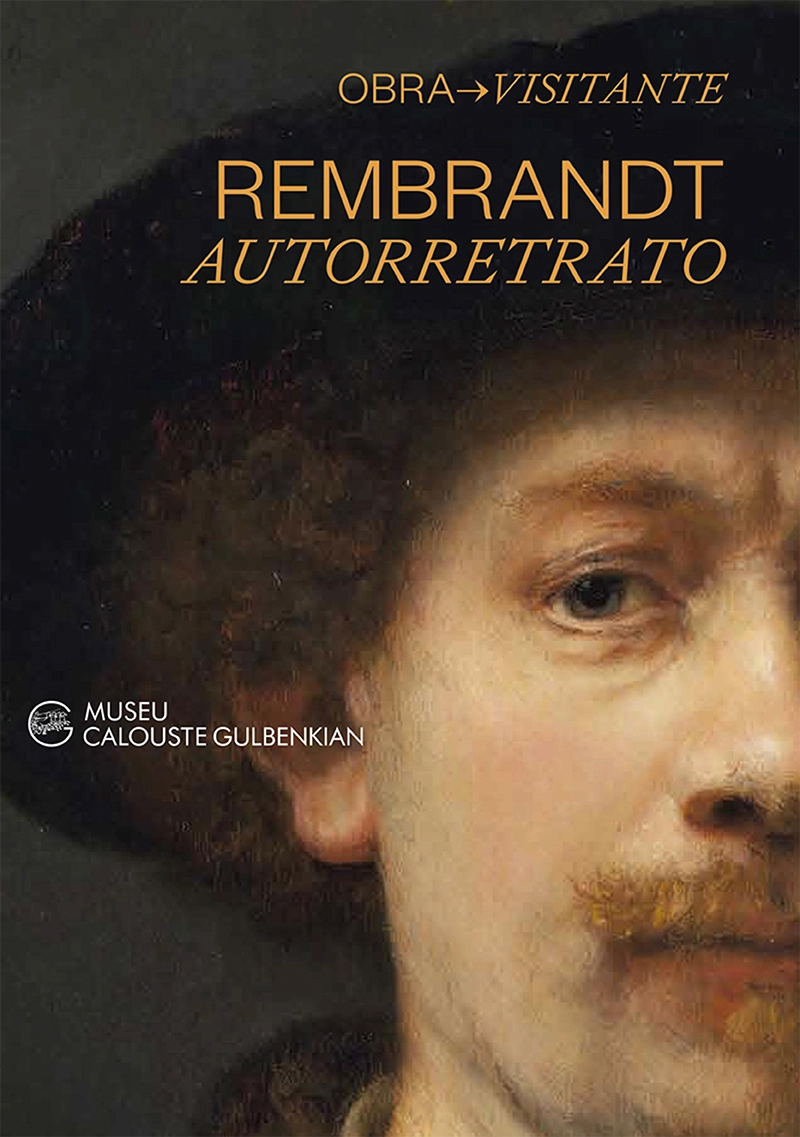

Visiting Artwork: Rembrandt, 'Self-portrait wearing a beret and two chains'

Event Slider

Date

- Closed on Tuesday

Location

Calouste Gulbenkian MuseumIn the Visiting Artwork initiative, the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum welcomes works of art from museums around the world, creating unprecedented and sometimes unexpected dialogues with works from the permanent exhibition. The first Visiting Artwork comes from the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid and was made by Rembrandt van Rijn ca. 1640.

Self-portrait Wearing a Beret and Two Chains is an example of one of the Dutch painter’s favourite themes – self-representation under different roles.

This work will be displayed in the room dedicated to Dutch painting, side by side with the two paintings by Rembrandt bought by Calouste Gulbenkian, Portrait of an Old Man and Pallas Athena.

REMBRANDT BY REMBRANDT

The oeuvre of Rembrandt (1606-1669), which consists of over three hundred paintings and whose artistic legacy remains one of the most powerful in Western art, includes some forty self-portraits. In this category it is possible to identify, from the end of the 1620s until the year of his death, in an often intriguing output, several subcategories or groups of compositions in which the artist deliberately takes on different roles.

Rembrandt initially depicted himself in a manner quite faithful ‘to his image’, in a deliberately conventional way. What is significant in understanding the self-portraits is the fact that, from 1629 onwards, the painter purposely manipulated his image in a considerable number of self-portraits.

The use of exotic props also gave rise to a category of figuration that oscillated between the portrait à l’antique and the portrait ‘in oriental attire’, the two not always easy to differentiate. However, Rembrandt rarely depicted himself in a formal manner, in the fashion of the time, with the exception of Self-portrait of the Artist as a Burger (1632, The Burrell Collection, Glasgow).

Particularly revealing in terms of understanding the self-portraits is the depiction of Rembrandt in the distinctive clothing of his profession, a type of composition that points towards the depiction of the painter as a painting theme in itself. The Painter in His Studio (c. 1628, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), probably a fairly faithful recreation of Rembrandt’s studio, transports the creator into the (mental) creative space.

Towards the end of his life, around 1665-1669, the painter would reprise the theme in Self-Portrait with Two Circles, Kenwood House, The Iveagh Bequest, London), depicting himself surrounded by the accoutrements of his profession. In the composition in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, which can be dated to around 1640, the artist is depicted wearing dark clothes, with a fur-trimmed smock and two gold chains, on a neutral background.

The costume is identical to that worn by Dirk Bouts (1410/1420-1475) and Rogier van der Weyden (c. 1399-1464) in two prints by Hieronymus Cock (c. 1510-1570) that were published in 1572 and which inspired him, suggesting a tribute to the Flemish artists of the 15th century.

The constant introduction of variations in clothing, which transports the artist in time or brings him back to his own time, or both simultaneously, also served the painter as a means of establishing his place within a long artistic tradition, in which he equalled or even rivalled the great masters, as seems to be the case with Self-Portrait (1640, The National Gallery, London), in trompe l’oeil, where he takes up Albrecht Dürer’s famous pose in Self-Portrait (1498, Prado Museum, Madrid).

Specialists in Rembrandt’s work have identified in this type of portrayal, in which several levels of information contribute to the final result of the composition, a combination of two determining factors: on the one hand as a portrait of a uomo famoso, on the other hand as an autograph specimen of the reason of the fame – an exceptional painting technique.

This impressive corpus of compositions, supported by a convincing illusion of reality, which brings us face to face with a particularly compelling characteristic of the artist’s genius – Rembrandt fecit Rembrandt. There is a resulting conviction that the function (or functions) of the self-portrait in the painter’s work, at times suggesting a possible interpretation and at others conveying a tangible reality, ultimately converges towards an iconography that is without parallel in Western painting and which never lets up. Perhaps this is the supreme challenge of art, to question and surprise us.

Luísa Sampaio

Paintings curator, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum.