(Re)Visionary Navigations of Cultural Memory

Born in Maputo, Mozambique, in 1958, to a family of Portuguese descent, Ângela Ferreira’s formative years were marked by frequent displacements, moving between marginocentric capital cities, between contested colonial margins and centers. Pursuing professional opportunities, Ferreira’s family relocated from Mozambique during the early years of the colonial war and struggle for independence to apartheid South Africa, then to London and, in Ferreira’s case, to Lisbon in the years leading up to the 1974 revolution that overthrew a regressive fascist dictatorship and dissolved the most recalcitrant of European colonial empires.

Ferreira returned from Lisbon to Cape Town, where she completed her MFA at the Michaelis School of Fine Art at the University of Cape Town and began her professional life as an artist and professor of sculpture during years of transition. In 1989/1990, with a first grant from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, she returned to Portugal to pursue sketches and sculpture based on the modernist structures depicted in the mural Emigração by Almada Negreiros.

Working between Maputo, Cape Town, and Lisbon, where she settled in the 1990s, Ferreira’s installations have consistently bridged cultures, disciplines, documentary and imaginary, critical and creative discourses, post-modern/post-colonial ethics and modernist aesthetics through its focus on form and place.

From early installations such as Sites and Services (1992) and House Maputo: An Intimate Portrait (1999), through her representation of Portugal with Maison Tropicale at the 2007 Venice Bienale and For Mozambique at the 2008 São Paulo Biennial, to more recent works such as South Facing (2017), Ferreira’s sketches, sculptures, and installations seek compelling ways of making and engaging art in the wake of utopian constructs and dystopian critique.

She pursues a trajectory in the margins and the mundane of contested cultural imaginaries, recovering recursive histories in prospective traces, recognizing historical ironies as horizon.

Casting off from modernist architectural moorings, transposed and transcultural modernist aesthetics, Ferreira navigates rather treacherous tides of post-modern cultural memory and post-colonial critique with a sleek sense of form and a sensibility attuned to exquisite elements within the (dys)functional.

She relies on a motley set of navigational tools and traditions—sculpture, sketches, documentary photography—building on, drawing on, and bearing witness to collective and individual memory, complex cultural loss and longing. There is no pretense regarding the political undercurrents negotiated through her aesthetic maneuvers.

Her carefully crafted installations—including the minimalist, neo-modernist sculptural works for which she began to be internationally recognized with Sites and Services, discomfiting photographic documentation of cultural pretexts and subtexts (such as the sanitary facilities included in that same installation, a wall of images that Ferreira recalls early critics claiming ‘dirtied’ the clean modernist lines of her sculpture), recuperated and reframed cultural fragments (films, books, other documents instigating and inserted within her sculptural works), and often sketches (not only preliminary, but made throughout the process—confront the viewer with unsettled, unsettling vision, revisionary perspectives on the past, visionary reorientations of the present.

The ballast that steadies Ferreira’s craft in turbulent cultural tides is memory—traces of her own cultural contexts and transcultural crossings, transposed modernist architectural forms, records and reconstructions of everyday life in late colonial and post-colonial contexts, reassembled according to a post-modern architectonics.

Ghost ships of sorts, skeletal abstractions, composites of fraught revolutionary fragments, Ferreira’s historically revisionary, avant-garde works have ably guided us through troubled post-colonial memory for decades now, towards an ethical aesthetic response and responsibility.

Ângela Ferreira’s For Mozambique [Model n.º 3 for propaganda stand, screen and loudspeaker platform celebrating a post-independence Utopia] is a strangely beautiful scaffolding of song, story, and history, celebratory and hopeful. Yet this hope sails toward a horizon of historical irony.

This third and last model, of an initially projected seventeen, looks somewhat like a sleek skeletal ship, a self-contained modernist construct with masthead and crows nest, screens as raised sails, vessel trailing into wake with waves of framed word and image. Built for São Paulo’s 28th Biennial in 2008 and acquired by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in 2009 for its Modern Collection, it is as much ark as barque.

The work is retrospective, recalling euphoric Marxist moments and movements in opposing halves of the twentieth century and opposing hemispheres. Its modernist bones and ideological covenant have been displaced countless times over in shifting historical tides. Yet it takes the prospective from of a propaganda platform, modeled after early Soviet agitprop designs, displaying celebratory documents and documentary films from the first years of Mozambican independence.

Despite its relatively simple structure, the work’s spatial, temporal, and semiotic dimensions are complex. Ferreira’s characteristic conjunction of minimalism and multivalence is compelling. Her recuperated, reproduced, (re)projected, and (re)constructed components together comprise a threshold construct, a liminal chronotope (structuring of time and space) that bespeaks Ferreira’s transdisciplinary, transhistorical, and transcultural consciousness and conscience. For Mozambique [Model n.º 3…] draws direct lines between distant places and discrete moments, indicating correlations between post-independence Mozambique and post-revolutionary Soviet Russia.

It draws on diverse aesthetic traditions, interpolating different spatial and temporal architectonics: incorporating video footage of workers singing and dancing in celebration of Mozambican independence within the 1975–7 short documentary film Makwayela directed by Jean Rouch and Jacques d’Arthuis and of Bob Dylan singing of time he would like to spend ‘Among the lovely people living free/Upon the beach of sunny Mozambique’, moving pictures projected on either side of a screen set within a wooden structure built according to the original 1922 designs drawn up by the Latvian-Russian Artist Gustav Klucis for the propaganda division of the Russian Communist Party. A non-narrative sculptural installation, it incorporates storied and historied dimensions.

These include the stories and histories represented by found fragments—not only the films, but also reproductions of stamps issued in 1979 to commemorate the fourth anniversary of Mozambique’s Independence and documents related to commemorative filmmaking and television broadcasts. There is the story and history implicit in the reconstituted architectural forms: the skeletal wooden framework transposed and transformed, like ideology, social architecture, and revolutionary art.

The artistic execution of an equal euphoric idealism also recalls its aftermath, continued inequity, entrenched argument, armed conflict, censorship, and in the case of the constructivist Latvian-Russian artist committed to art in service of Soviet propaganda, eventual incarceration and execution during Stalin’s purges. The architectural form, seemingly benign or even intended as beneficent, is not innocent but implicated in colonial and post-colonial conflict, adrift amidst its devastating consequences, made of the detritus of its creative imaginary.

Ferreira’s For Mozambique models likewise present history adrift. Yet her characteristic modular sculptural abstractions, however deconstructive, are not shipwrecks. They are elegantly disconcerting and discomfiting, but neither elegiac, nor disorienting. However politically pointed and socially incisive, her work is not despondent or derisive. Rather, her work recuperates, reconstructs, relocates, and reframes past cultural discourses, reorienting the present (re)constructively.

Ferreira intentionally works with everyday building materials, often those of her geo-cultural point of reference—the plywood of a construction site on the edges of Cape Town or Maputo or Lisbon.

Her work is marked by that modernist ethics and aesthetics defined by Russian formalists such as Shklovsky and Tynianov in terms of defamiliarization and stylization that makes us see what we can no longer see, feel what we can no longer feel, confront what we have forgotten, enlivening by estranging both life and literature, or art. Rather than making us trip over a stone to make the stone stony again, Ferreira allows us to see formal and material properties of plywood utilized in sleek modular sculptural form, of song and dance projected without sound, moving with the rhythm of the skeletal wooden structure.

Ferreira’s composite work, without definitive pronouncement, entails the critical and creative attentiveness Bakhtin correlates with heteroglossia, polyphony, dialogism, doubled and divided consciousness crossing between spaces defined by discrete socio-ideological and formal, literal and literary speech genres (or kinds of art and architecture). Ferreira’s work not only draws into dialogue speech and song, image and cultural imaginary from disparate cultural contexts. The conjunction of these discrete storied, historied fragments reflects the political pretexts, contexts, and import of each from the critically insightful standpoint that Bakhtin associates with a critic’s concomitant “insideness and outsideness” and with work transposed into ‘Great Time’.[1]

We are drawn into the workers’ dance steps and Dylan’s song, into the epic recounted on repeating stamps, into the waves of framed newsprint, yet we also stand at our historical and aesthetic distance, reflexively aware of the repositioning of this propaganda stand in a gallery, responsible to this political and art history reframed in this context. Extending to visual art Deleuze and Guattari’s claims regarding the political purport of the ‘multiple deterritorializations of language’ inherent in all ‘minor literatures’,[2] we may consider how Ferreira challenges hegemonic historical claims through displacement, digression, the infusion of diverse, marginal discourses. This challenge is not only political, but aesthetic, not only a matter of revisionary history, but also of visionary art.

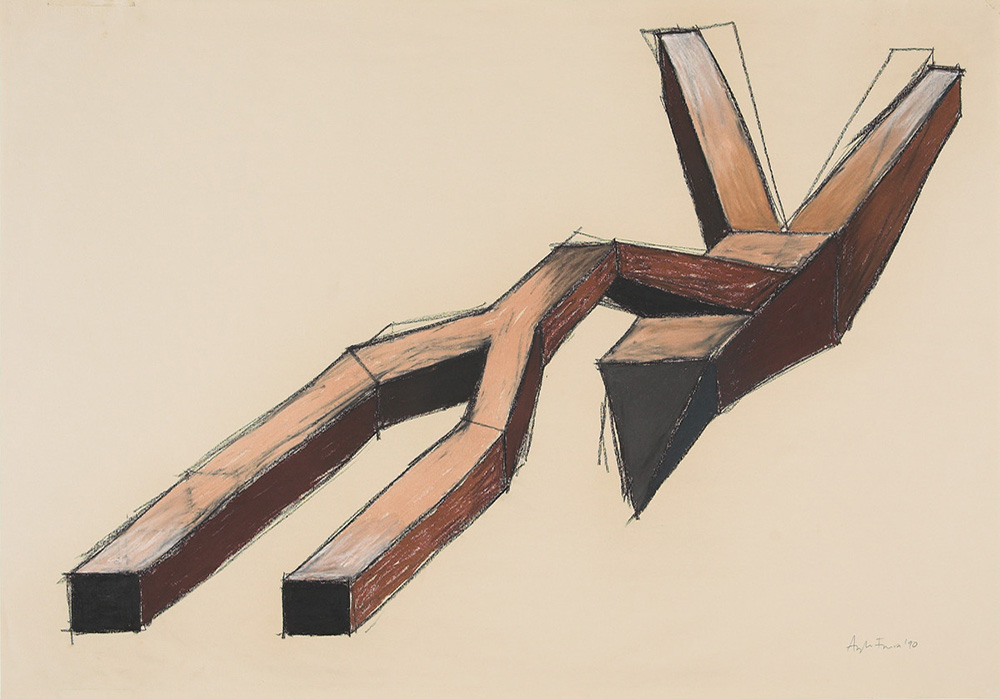

Despite a clarity and certainty suggested by the striking structural simplicity, Ferreira’s work is full of traces of the artists’ hand at work. It rewards close looking with new understanding of materials and methods. The documents included in the various For Mozambique models foreground the process of making films, include printed text and hand written annotations. There is no erasure in either early or recent sketches by Ferreira in the Calouste Gulbenkian Modern Collection, where pencil grid and searching line, drawn and redrawn, remains visible beneath pastel chalk. In the untitled drawings made during her first stretch as an artist in Lisbon in 1989, affiliated with Ar.Co. and supported by a grant from the Gulbenkian, black lines underlie and outline white, grey, blue, ochre, umber chalk surfaces.

Formal dimensions of the objects are defined by beautiful planes of color made with chalk lines that alternately reveal and obscure the artist’s hand. Dense black, dark blue grey, and burnt umber fill the plane, while lighter ochre, umber, grey, and white are scratched onto more open surfaces, on which one can trace gestures, glimpse Fabriano paper ground through the gaps. Neither dense plane, nor open scrawl obscure the searching black lines, which can be seen through, but also extend beyond and encompass colored planes. The functional dynamics of Ferreira’s drawings lie in the lines that seek shape and scratch surface, in confronting viewers with a process recovered rather than covered up. The early sculptures in the Modern Collection work in the same way. Consider Escultura III from a distance and it seems sleek finished form. Approach the surface and there are pencil guidelines drawn on the wooden structure, visible on the upper as well as underside of the piece.

The countersink holes rip into the plywood; the screws are oxidized. Time is implicit in the work’s modernist references and inscribed on the work through traces of its making and its being seen. Ferreira’s instructions are that the books included in her Double Sided installations are to be handled, so that they have, in fact, disintegrated.

In a recent conversation, in which she insisted that the point of her installations was interactive understanding of time and place and process, Ferreira seemed bemused by curatorial dismay and uncertainty regarding whether to replace the books, leave them in place but not allow them to be handled, or let them simply fall apart through further art to be touched.

Ferreira notes the indivisible elements of For Mozambique [Model n.o 3…]. Ferreira’s installations, interactive or not, invite unconventional engagement. Ferreira’s sketches and documentary photographs are not merely studies for finished sculptural works. Conjointly they comprise an intentionally unfinished finished work, an unfinalized dialogue. Ferreira invites us on board, to salvage and seek alongside.

[1] Mikhail Bakhtin, Speech Genres and Other Late Essays [Эстетика словесного творчества (Estetika slovesnogo tvorchestva)]. Ed. C. Emerson & M. Holquist. Trans. V. W. McGee. Austin: Univ. of Texas Press, 1978. Cf. The Dialogic Imagination, 1981.

[2] Deleuze, Gilles & Félix Guattari. Pour une littérature mineure. Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1975. [Kafka: Towards a Minor Literature. Trans. Dana Polan. Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 1986.]