“Poetry is in the Street”

Posters by Maria Helena Vieira da Silva

Part of the history of the Carnation Revolution and the tumultuous months that followed in the transition to Democracy has been preserved in posters. In a blaze of colour, political messaging and slogans, posters offered some of the most eye-catching art of this period. They were the work of artists such as Marcelino Vespeira, João Abel Manta, Henrique Ruivo and Artur Rosa, to mention just a few. And Maria Helena Vieira da Silva.

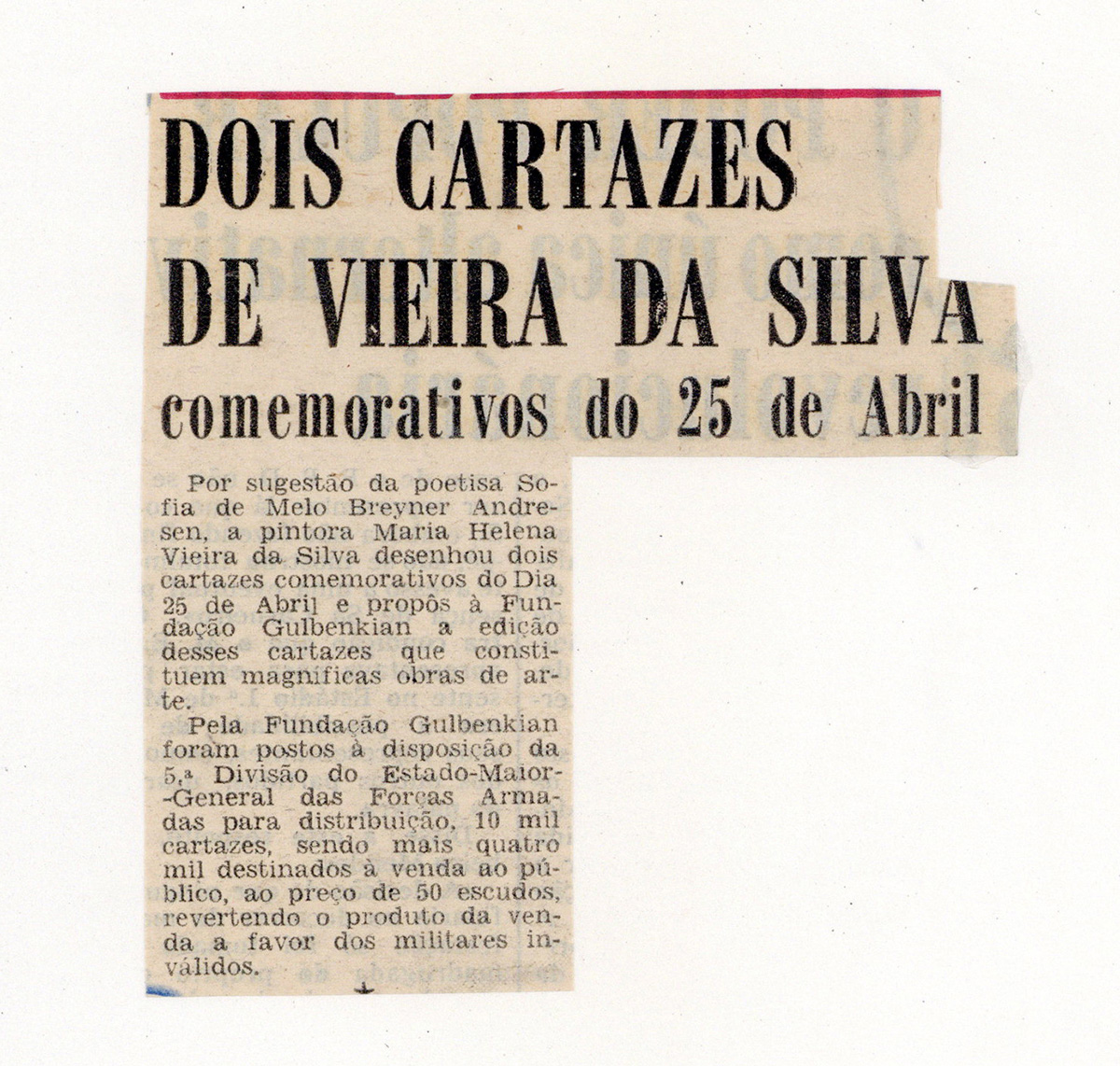

It was the poet Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen, a friend of Vieira da Silva, who, in early 1975, suggested the idea of a poster marking the first anniversary of the Revolution of 25 April 1974. The slogan was taken from a poem she dedicated to the members of the Portuguese Socialist Party (A poesia está na rua, Poetry is in the Street), and was featured in many of the placards carried by marchers in the May Day celebrations that year.

The artist, who was then settled in France, dividing her time between Paris and Yèvre-le-Châtel, avidly followed the newspaper reports of events in Portugal, and designed the two posters, with the speed urged on her by Sophia, at her house and studio on Rue de l’Abbé Carton.

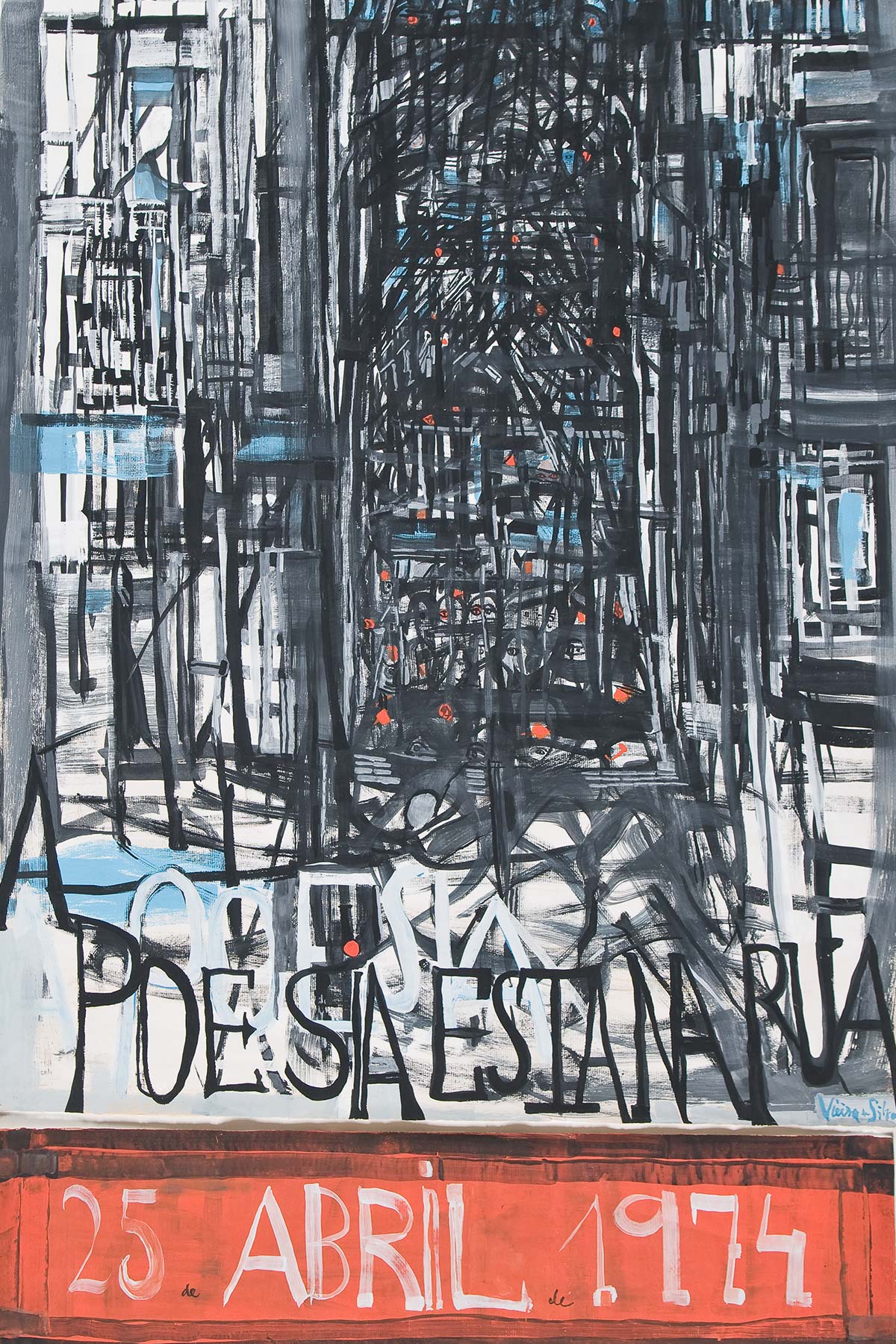

In actual fact, she initially designed a single poster. True to her visual language, which tended towards the abstract, Vieira da Silva used a format of 104.7 cm x 75 cm, in which she depicted the crowds converging on Largo do Carmo, the soldiers, the red carnations, and inscribed the words “A POESIA ESTÁ NA RUA” along the bottom. She then used a second rectangle, 20 cm x 74.2 cm, to form the base of the composition, where she proclaims the central theme of the poster — “25 de ABRIL de 1974”.

Whilst pleased with the result, she was not entirely sure. She was afraid her abstract vision of events might not be understood. So she set about designing a second poster.

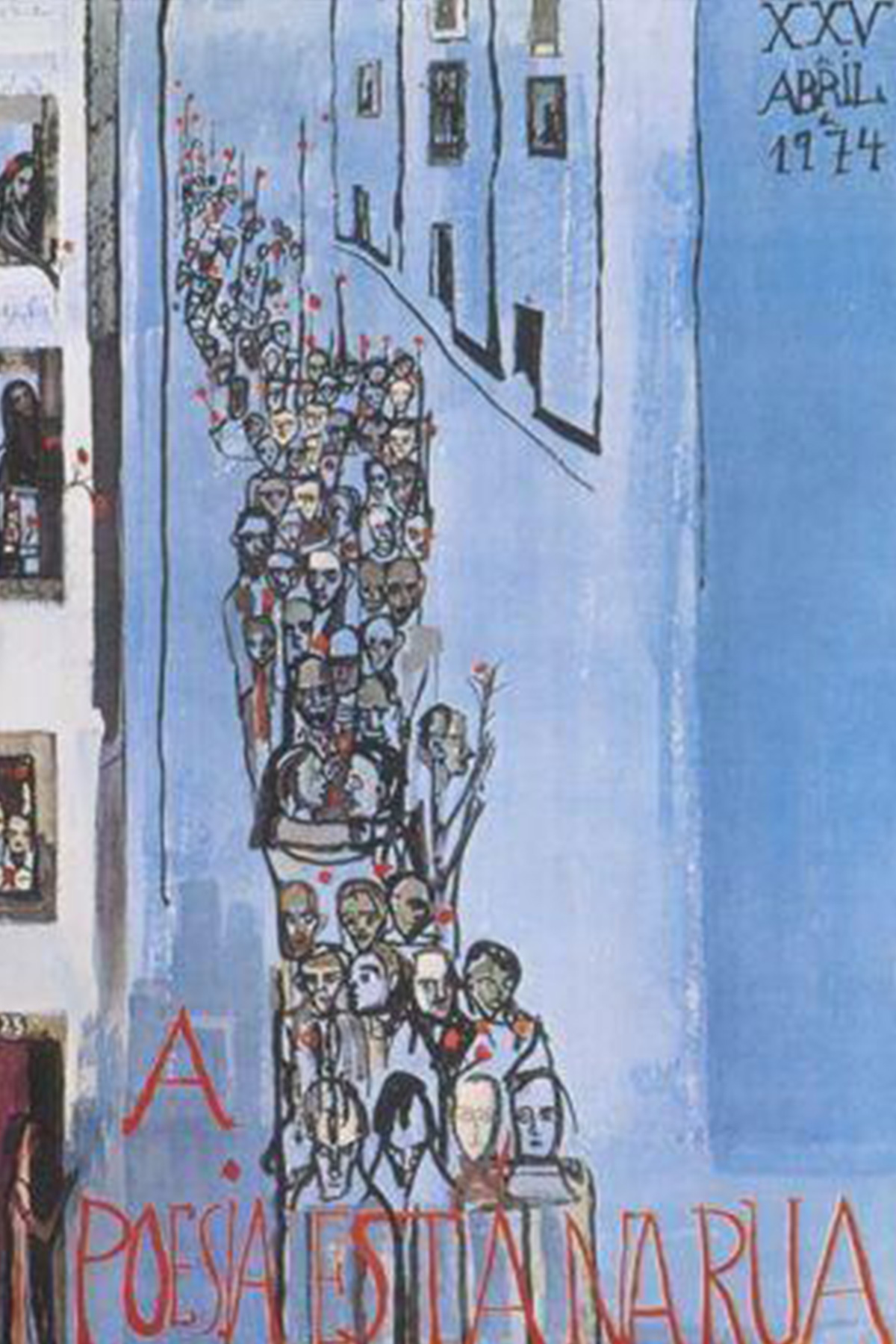

In a more figurative register, she took a format of 104 cm x 79.5 cm and illustrated the crowd marching along a street, soldiers with red carnations in their fists and guns, and people in the windows, also with carnations. In the foreground, the front door of a building bears the number 25, probably referring to the date of the Revolution, 25 April. In the upper right-hand corner, the words “XXV de ABRIL de 1974” indicate the subject, and the words “A POESIA ESTÁ NA RUA” run across the base.

Both posters are signed by the painter.

They are executed on paper. In addition to being light and practical, easy to transport and handle, paper is what Vieira da Silva preferred when working in water-based paints, such as watercolour, gouache, or tempera. For setting down ideas, the obvious choice was gouache because, along with tempera, it offered “the visual language best suited to recording her ideas and feelings with a speed and freedom which are not compatible with painting in oil”, as the art critic and close associate of the painter, Guy Weelen, later wrote, a propos of the exhibition “Vieira da Silva Paintings in Tempera, 1929-1977”, at the Gulbenkian Foundation, which he curated.

Sophia was full of praise for the artistic quality of both posters, despite a clear personal preference for the first. But the painter entrusted them both to her.

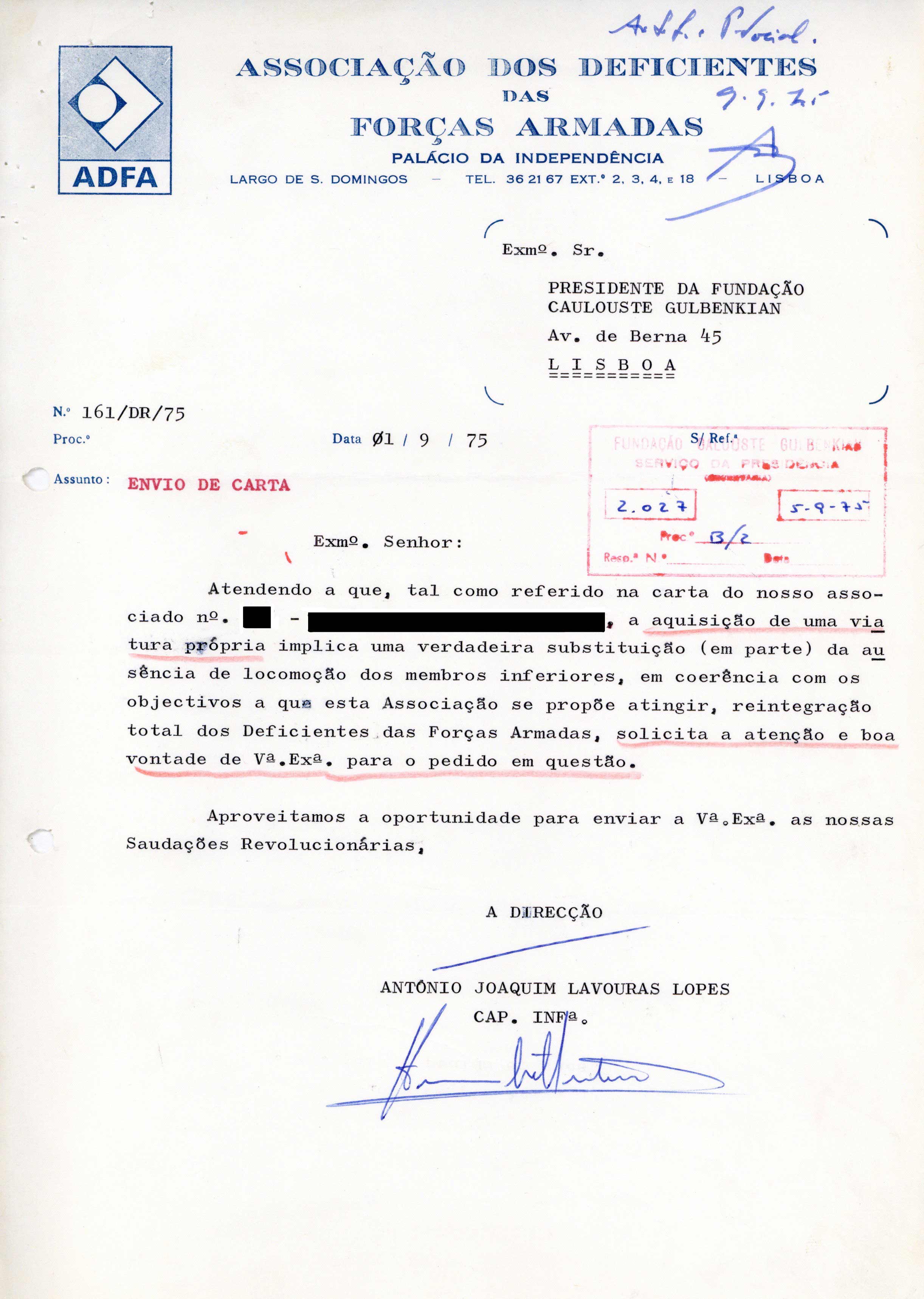

Vieira da Silva and Sophia de Melo Breyner decided that the proceeds of the project should go to charity. The long colonial war (1961-1974) had taken a heavy toll on a whole generation of young Portuguese men. As well as thousands of dead, military service in Africa had left many others wounded and disabled. Portugal now faced the difficult task of rehabilitating them for civilian life.

It was agreed that the proceeds from selling the posters (originals and reproductions) would go to helping these men, and in this mission the painter asked for help from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, which is of course, among other things, a charitable institution.

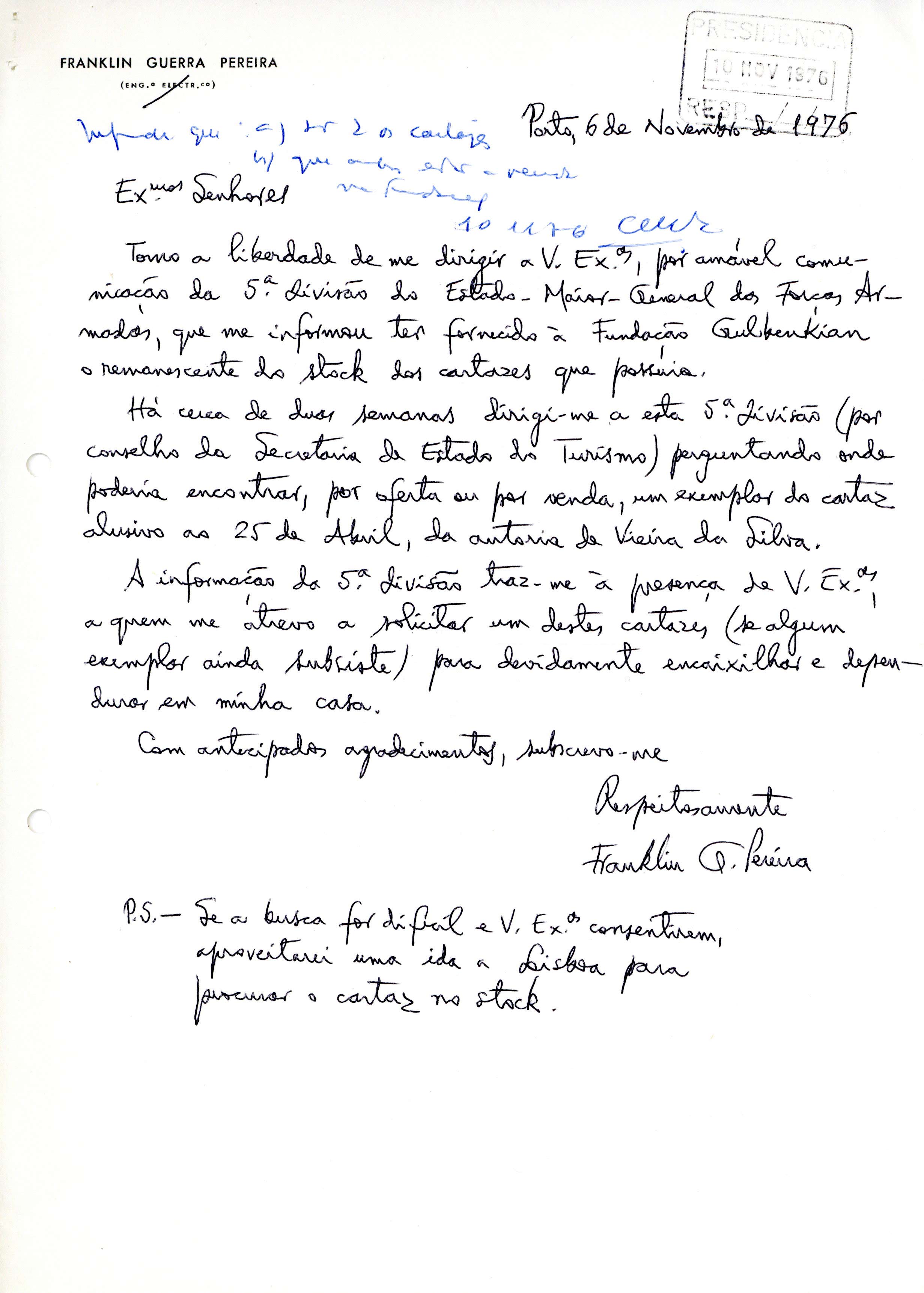

The posters appear to have been brought to Lisbon by Sophia, who handed them over to the Foundation.

In later March 1975, José de Azeredo Perdigão informed the board of trustees that “the painter Maria Helena Vieira da Silva has sent to the Foundation the originals of two posters she has designed with a caption from the poet Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen, alluding to the 25 of April, asking that the reproductions, to be executed by the Foundation, should be disseminated throughout Portugal, and the originals, or their value, donated to institutions serving the disabled war veterans”.

The trustees, “admiring their excellent artistic quality”, authorised publication of the posters. However, it stipulated that, before doing so, the Foundation should consult the 5th Division of the Armed Forces Chiefs of Staff, which was in charge of CODICE (Comissão Dinamizadora Central), the organisation responsible for producing printed material in support of the Armed Forces Movement (Movimento das Forças Armadas, or MFA), used in “cultural and civic mobilisation campaigns” aimed at the public, especially those less literate, in order to consolidate the “alliance between the People and the MFA” (famous examples of these are the posters designed by the artists Marcelino Vespeira and João Abel Manta).

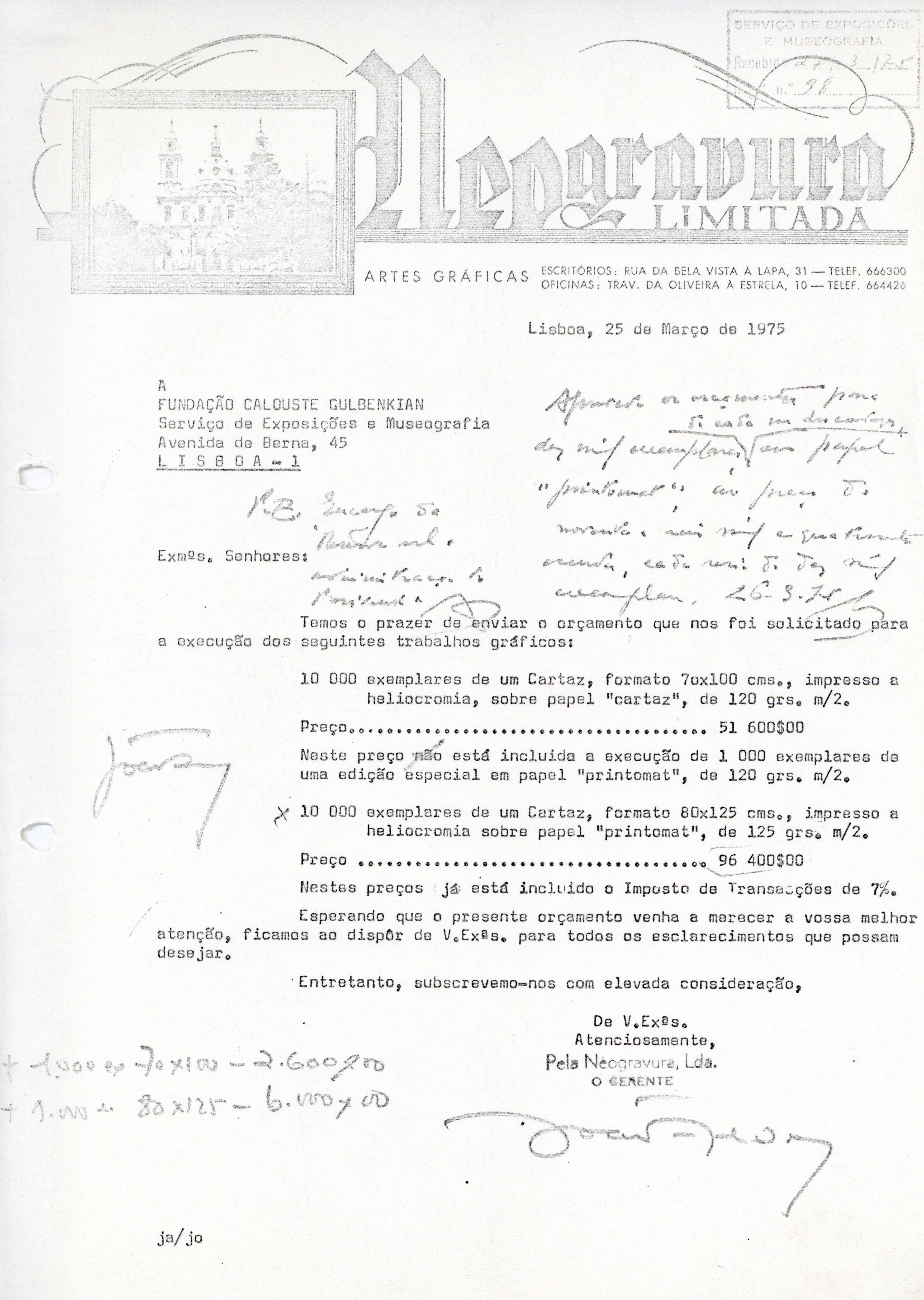

Having obtained the agreement of the 5th Division, the Foundation contracted Neogravura to produce ten thousand copies of each of the posters, printed “using colour photography on printomat 125 g. m/2 paper”.

José de Azeredo Perdigão immediately entrusted José Sommer Ribeiro, director of the Exhibitions and Museums Service, with the task of delivering a number of copies to Vieira da Silva, in Paris, conveying his admiration for the posters.

On his return to Lisbon Sommer Ribeiro reported to the chairman: “As agreed, I delivered to the painter Vieira da Silva 10 copies of each of the posters on the theme A poesia está na rua. Both the artists, and her husband [Arpad Szenes] and Guy Weelen, expressed their pleasure at the quality of the reproductions. As for what to do with the originals, the artist would like them to be sold and the proceeds given to the Associação dos Deficientes das Forças Armadas (Association of Disabled Veterans). Those posters not distributed free of charge, I think it would be a good idea for them to be sold by the Foundation or the 5th Division of the Armed Forces General Staff, the proceeds also going to the same Association”.

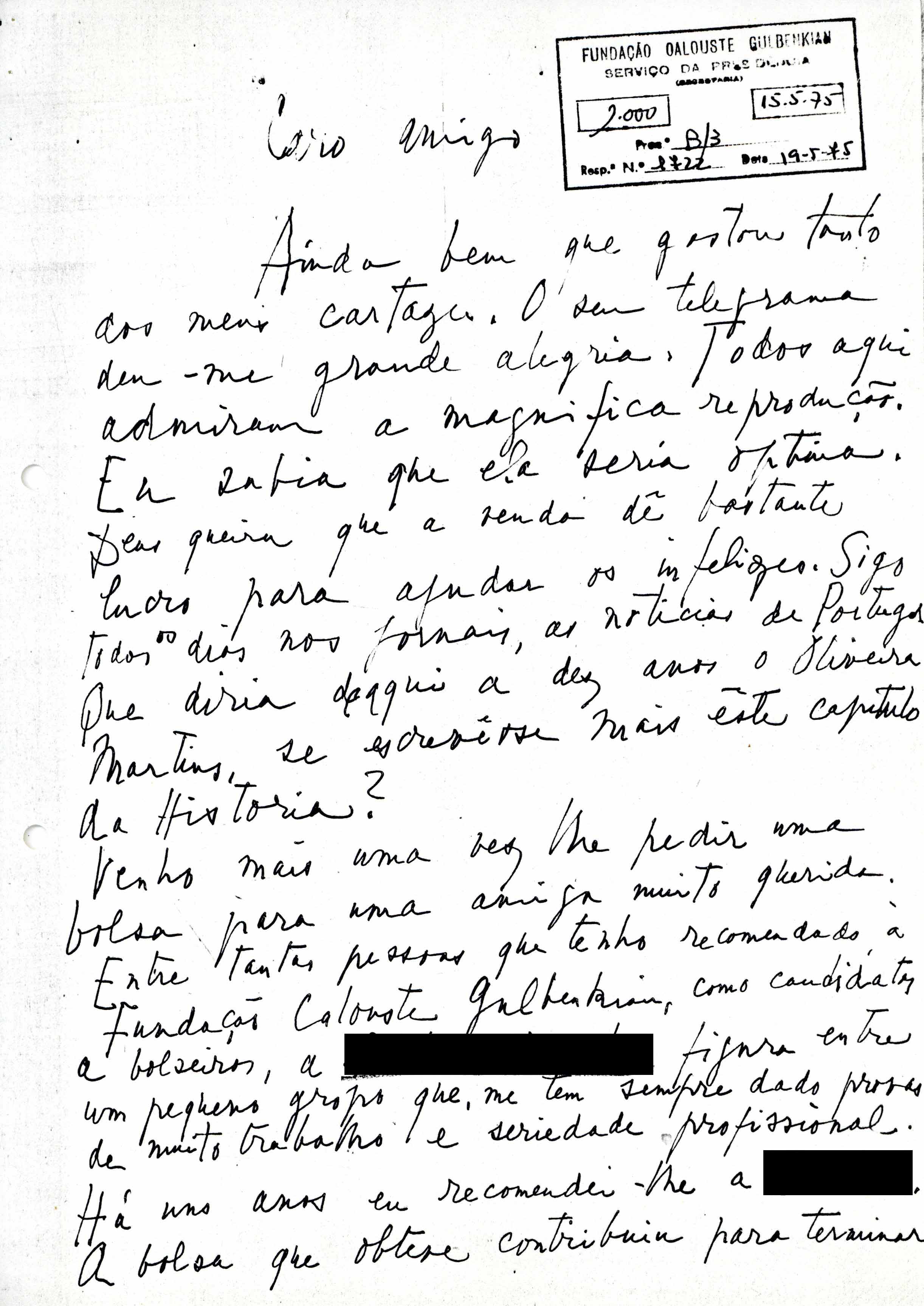

Confirming Sommer Ribeiro’s report, the artist also wrote to Azeredo Perdigão: “I’m pleased that you so liked my posters. Delighted to receive your telegram. Everyone here has admired the magnificent reproductions. I knew they would be excellent. Please God the sale will raise a good amount to help the poor men. I follow the news from Portugal every day in the newspapers”.

The posters were distributed by CODICE. However, they were not used in the same way as many others produced for this organisation, because, “in view of their quality, they could hardly be put up in the streets, where their life would necessarily be short”. Instead, they were distributed “to polling stations for the 25 April elections [to the 1975 Constituent Assembly], to military establishments, schools, etc., and presented to our main civil and military authorities, who showed great appreciation”, explained José de Azeredo Perdigão.

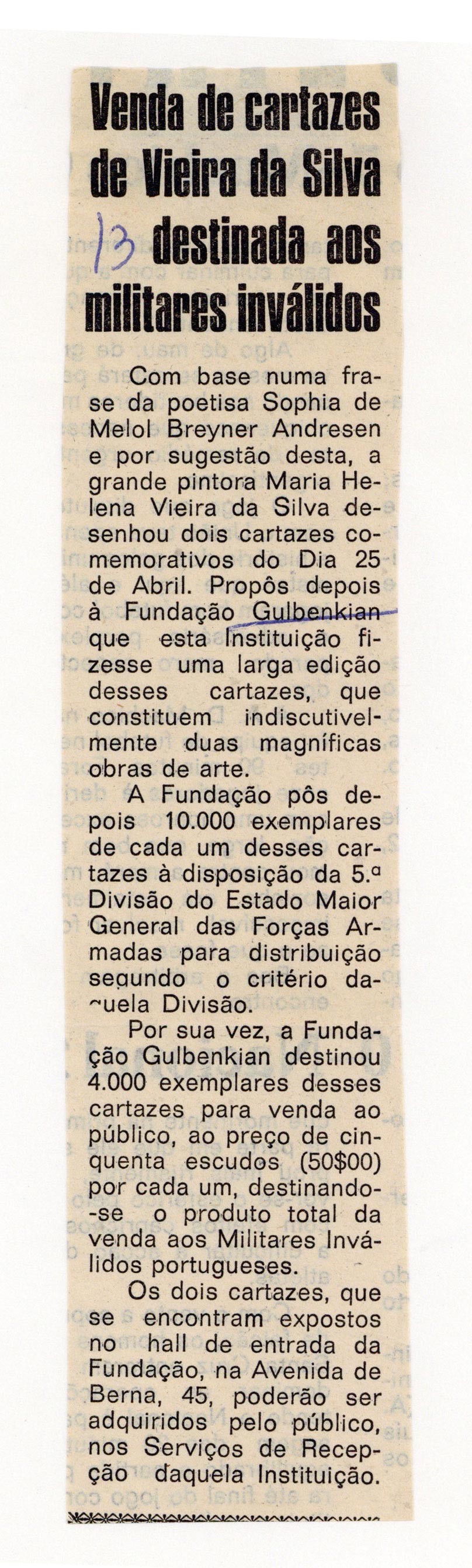

The Board of Trustees decided to place 4,000 copies of the posters on sale “at the reception desk in the Foundation’s main building and in the atrium to the Museum, for a price of 50$00 (fifty escudos) each”.

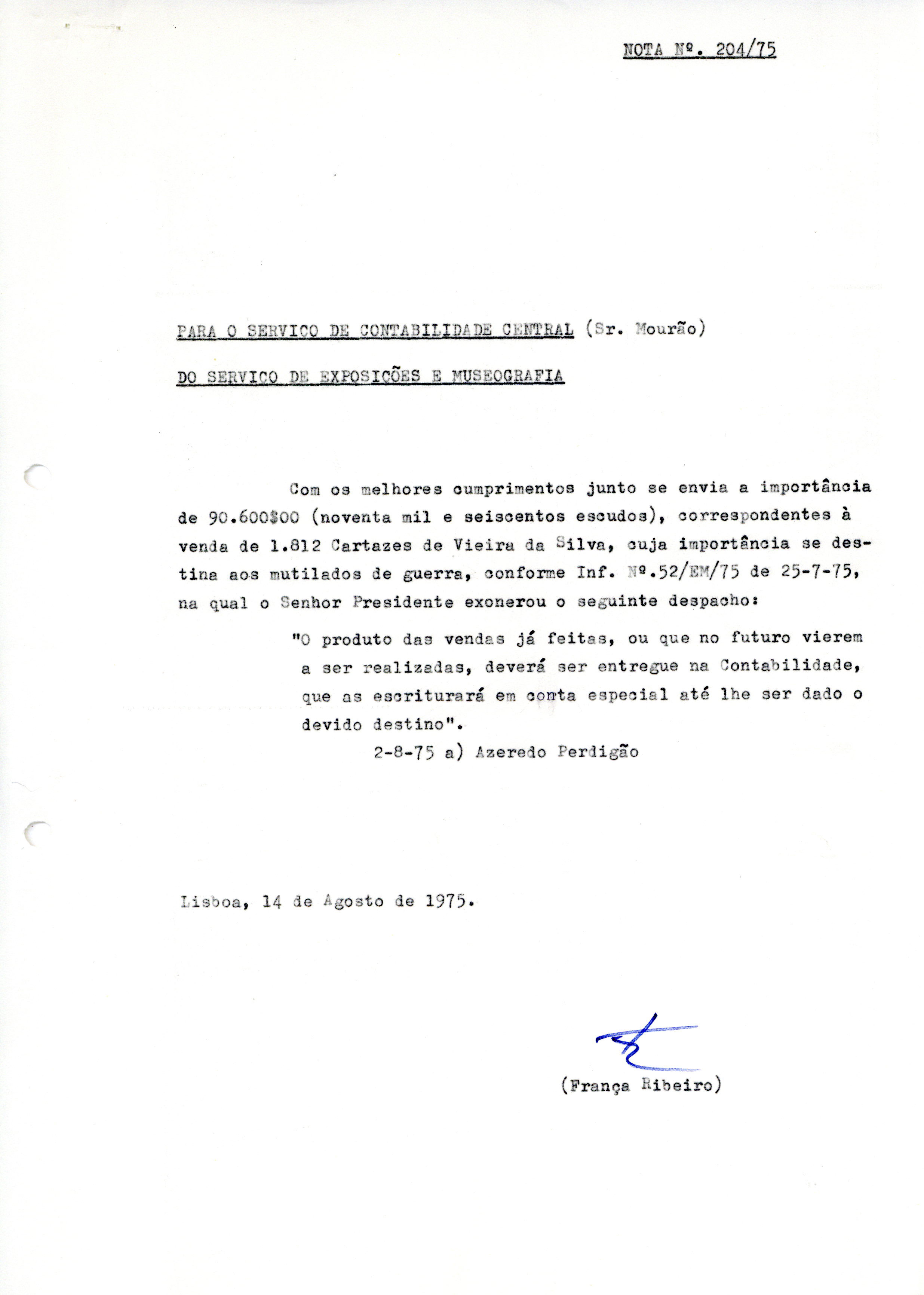

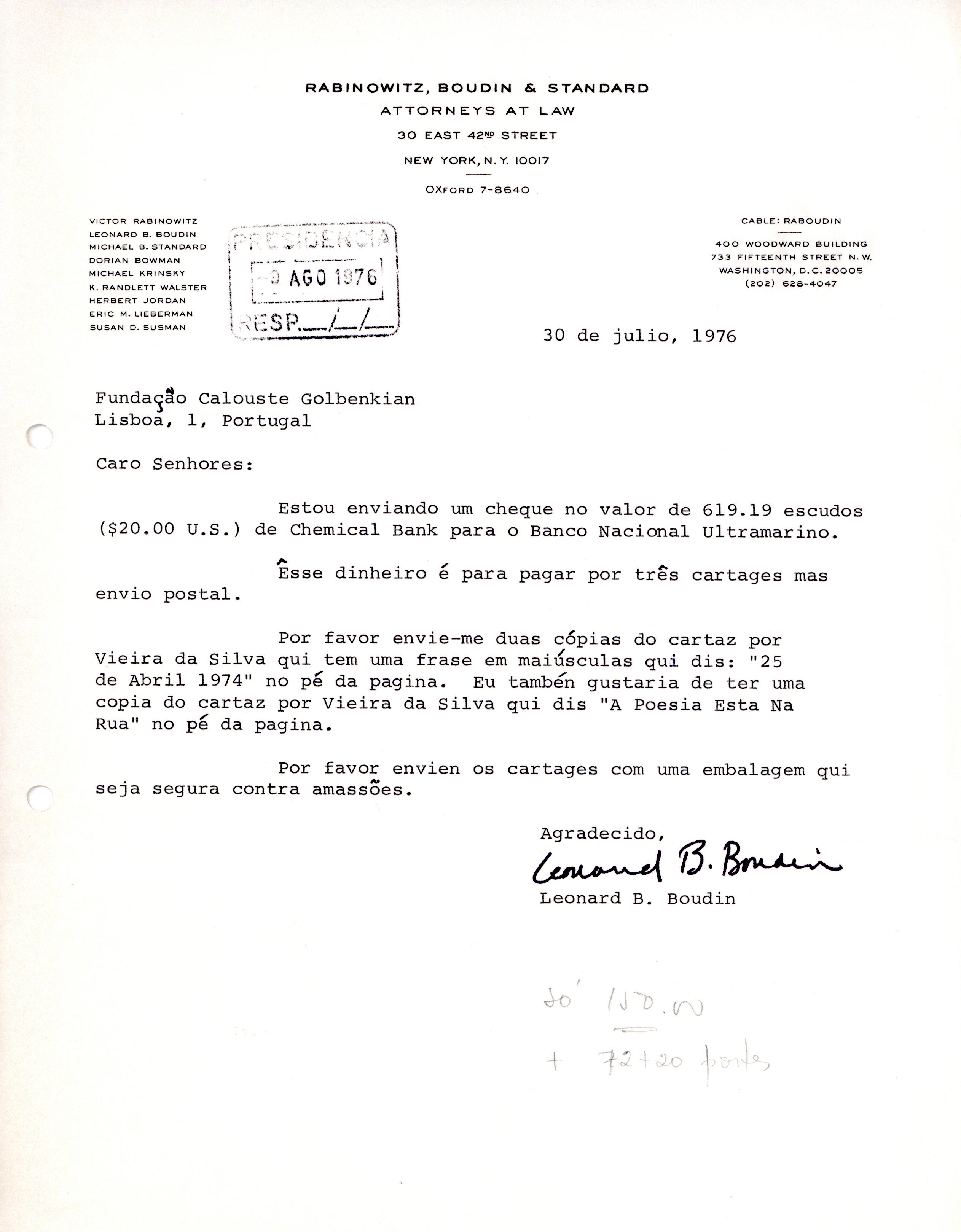

That same year and in subsequent years, sales of the posters were a success, not just in Portugal, but also abroad.

When the process of publishing, distributing, and selling the posters was completed, it had to be decided what to do with the originals. As early as 1975, José de Azeredo Perdigão had proposed to Vieira da Silva “that the originals should be kept by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation”. He sought the painter’s agreement for this course of action, asking her to indicate “the commercial value she would assign to these originals”.

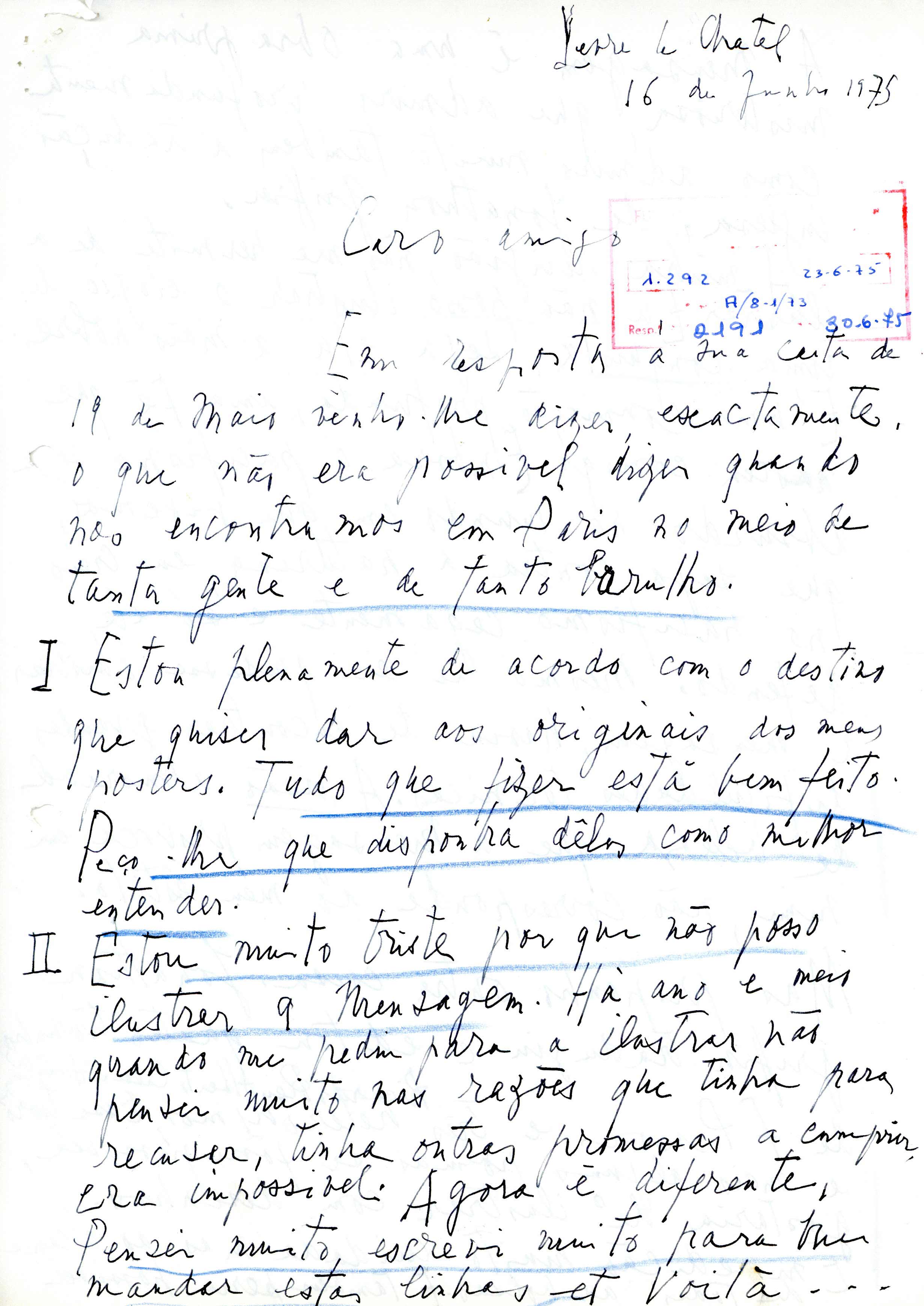

Shortly afterwards, Vieira da Silva wrote to Perdigão from La Maréchalerie, her property in Yèvre-le-Châtel, agreeing to the chairman’s request: “I fully agree with what you propose to do with my posters. I’m sure you will do the right thing. Please make use of them as you see fit”.

The chairman thanked the painter for her decision “on what to do with your posters”, and added that the Foundation would take, “in this regard, the best course possible”.

Perdigão informed the Board of Trustees of his discussions with Vieira da Silva. However, “because it is difficult, at the present time, to determine the value of each poster”, he proposed “that a specialist agency be entrusted with auctioning the posters, enabling the Foundation to buy them or not, depending on the prices reached in the bidding”. The proposal was accepted by the Board.

The Foundation purchased for itself one of the originals — A poesia está na rua I —, which was later included in the collection of the Centro de Arte Moderna. Research in the Gulbenkian Archives and external enquiries have so far failed to locate the poster A poesia está na rua II or to provide any information on its subsequent history.

However, we do know that, in November 1975, a significant sum was paid to the Associação dos Deficientes das Forças Armadas, possibly reflecting Vieira da Silva’s initial wishes. On the basis of a proposal from Augusto Reimão Pinto, head of the Social and Welfare Service, a donation of 300,000 escudos was made to the Association, “for the purchase of wheelchairs and motorised chairs for its members and to contribute to the purchase of vehicles”. This donation was to make a significant contribution to the rehabilitation and integration of many disabled veterans “who had suffered exclusion from society and employment”.

We know of later references by Maria Helena Vieira da Silva to the production of these posters.

In 1976, during the filming of the documentary on the painters, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, and her husband Arpad Szenes, entitled Ma femme chamada bicho, by José Álvaro Morais, a production of the Centro Português de Cinema with funding from the Gulbenkian Foundation, Vieira da Silva recalls the story of the posters:

“Sophia came to see me and asked me to do a drawing to celebrate the 25 April, a poster. And she spoke about the street, she wanted me to make a poster with people in the street, and then she went away and I started to work on a poster. And when I did it, I was pleased, but at the same time I said, “but this is very abstract, no one will understand what I’ve done, I’ll do another”. And so I did another with a street and people marching, in the street, and the soldiers and the red carnations. And then Sophia came back and saw the poster and said, “but your poster is very good, the first is very good, it was in the Largo do Carmo that things happened”, and then I said, “that’s true”, because when I read the newspapers, all I could see was Largo do Carmo, but I had forgotten and at the same time I know the Carmo very well, it’s one of the places in Lisbon I know best. But it’s curious, I didn’t see it, and in actual fact it’s the idea I had in my head, from what I’d read in the newspapers. So then she took the two posters and the Gulbenkian published them both.”

Later, in 1978, in a series of candid conversations between the writer Anne Philipe and the two painters, compiled and published in Paris that year by Éditions Gallimard, under the title L’éclat de la lumière (O fulgor da luz), Vieira da Silva was to return to the subject of the posters:

“One of my friends, Sophia Andresen, is a socialist member of parliament in Portugal and a writer, too. She asked me to make a poster to celebrate the 25 April. “Do what you like – she told me – the crowd, the street, whatever, but I need it quickly.” I thought about it and then got down to work, letting myself be guided by what came to me naturally. When I’d finished, I looked at what I’d done and was very worried: it looks like a stained glass window, you could see a church and some ruins. “At that time in Portugal – I thought – politics are the main priority, they’ll say I’ve done a religious painting. It won’t do, I’ll have to design something else” and I started to draw an old Lisbon street with a crowd and red carnations. When my friend came back, she chose the first design (she ended up taking both). I asked her “Won’t they say it’s religious nonsense? – No – she said – that’s where it all happened.” Then I remembered that when I read the news from Portugal I always imagined the demonstrations they described, in front of a church that I was very familiar with and that I loved, but I’d completely forgotten about that while I was working. But actually I have a good memory. The second poster is in a street very close to this church, although the church was not the centre of everything that happened, but rather the Gothic ruins of the Convento do Carmo.”

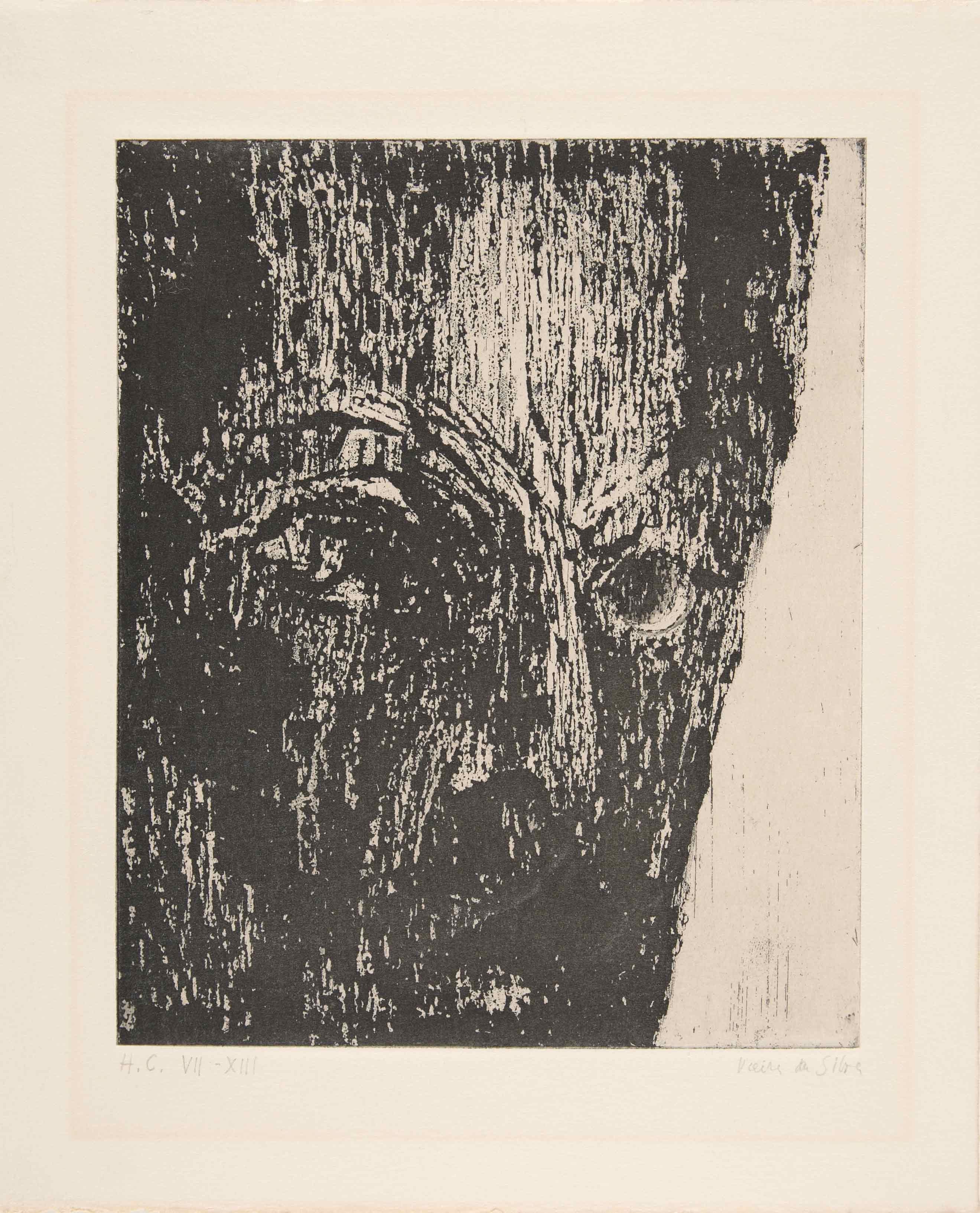

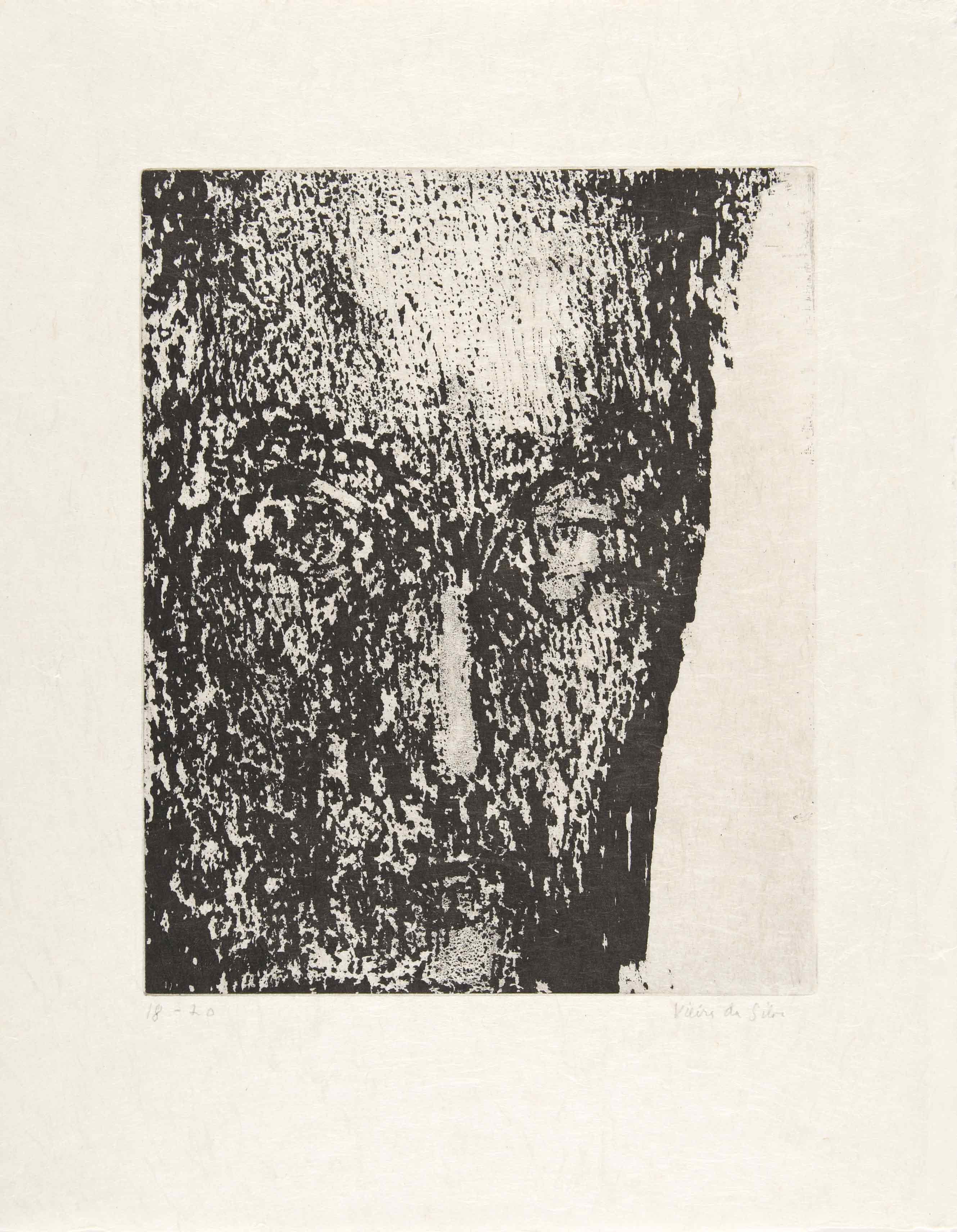

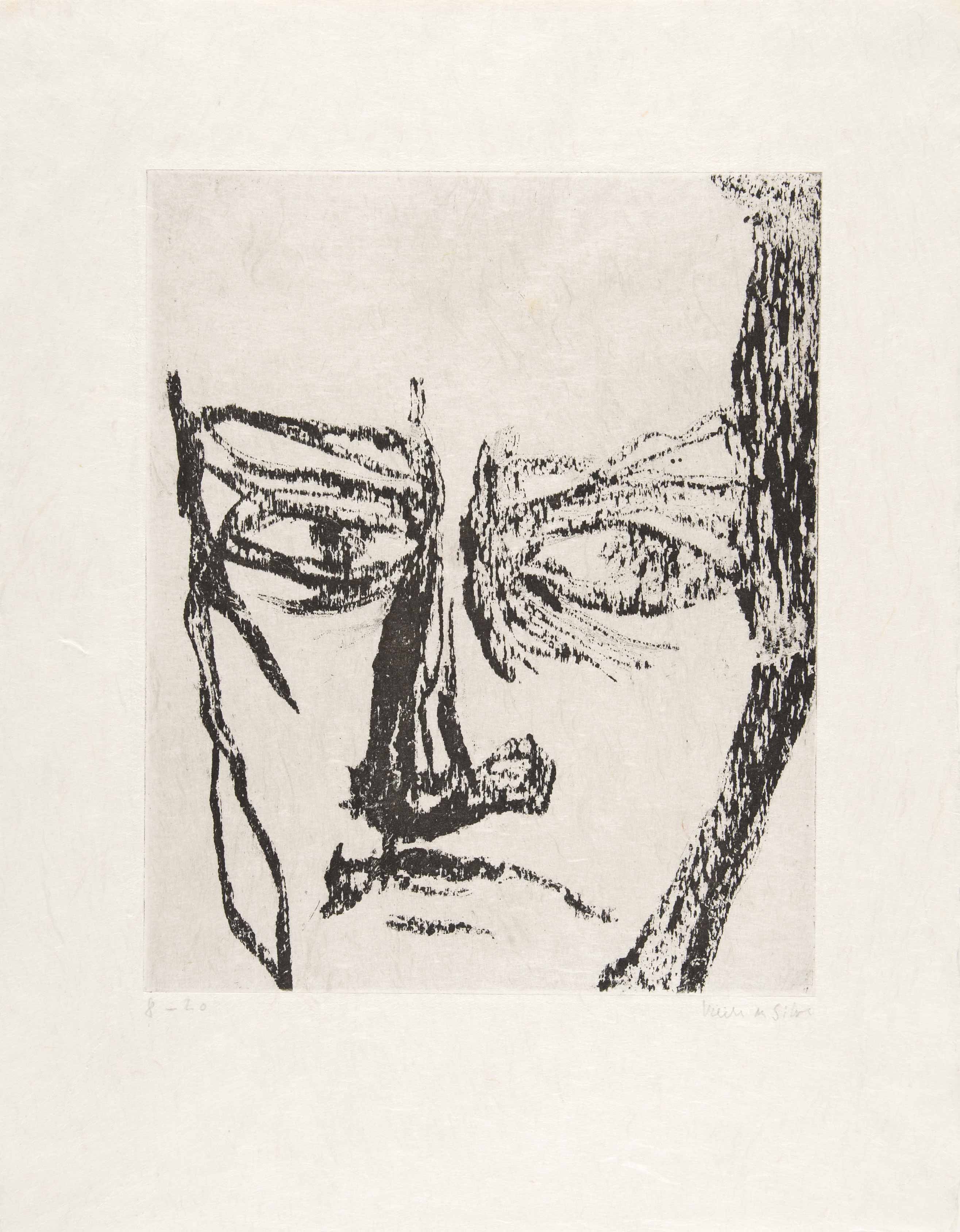

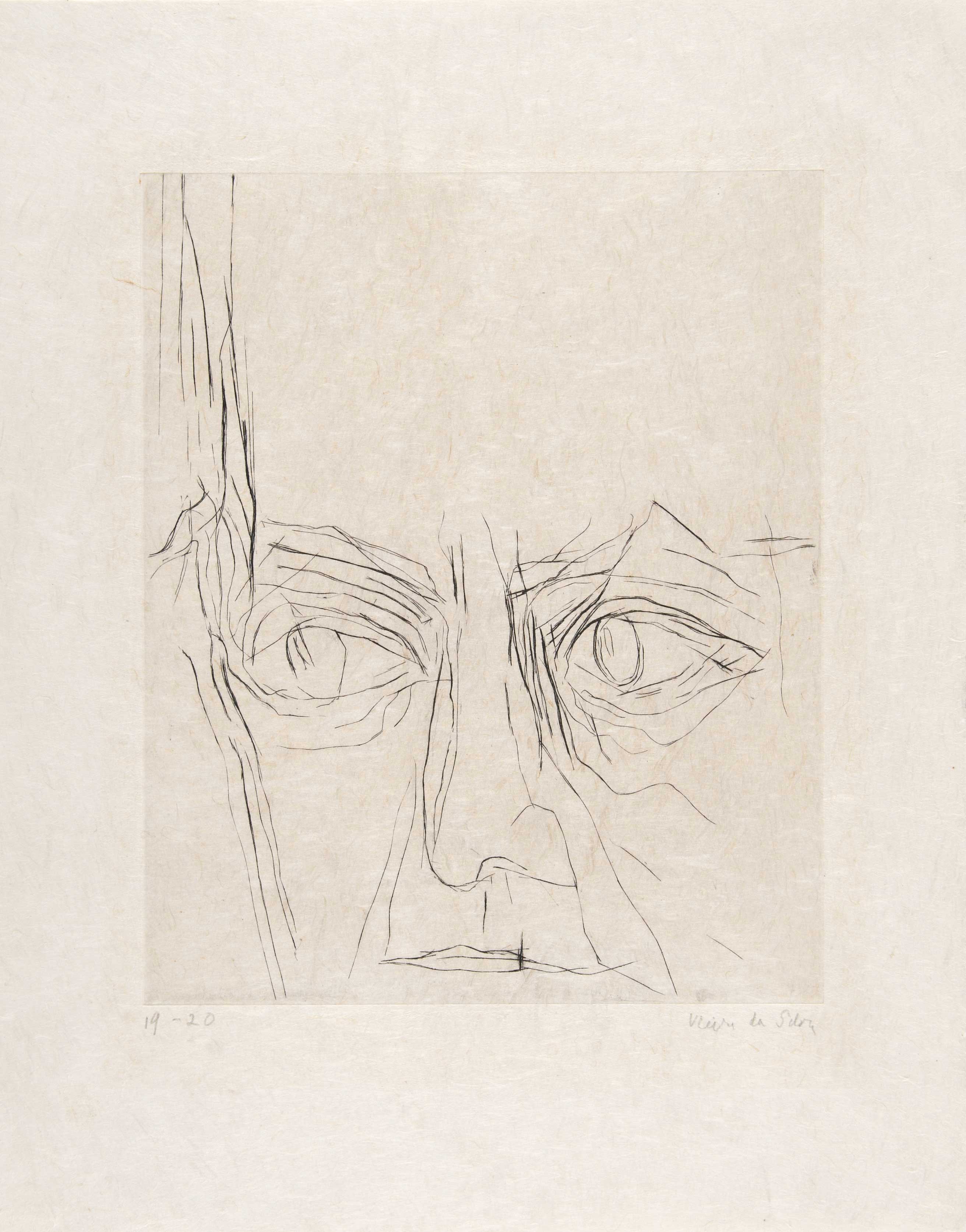

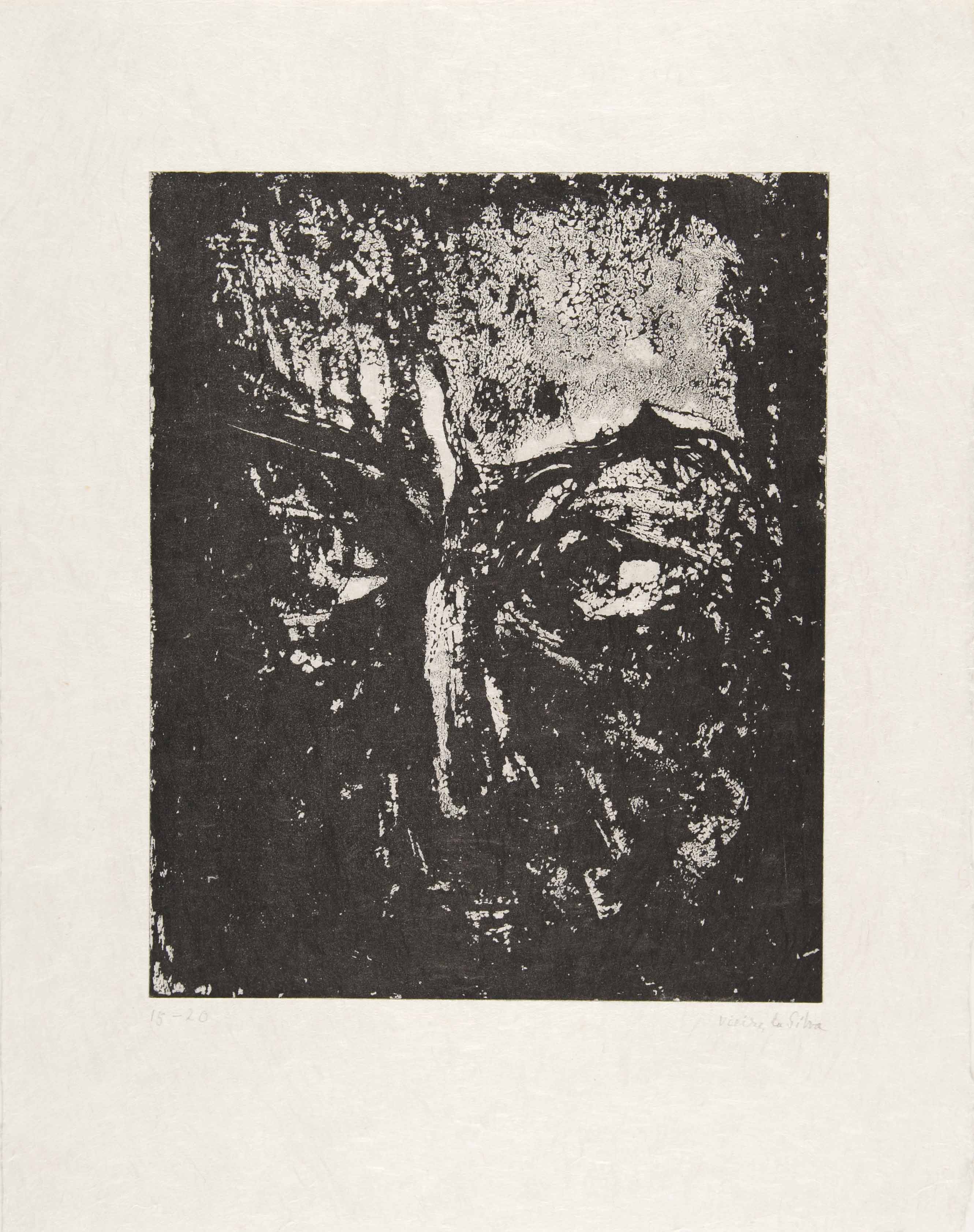

It is also curious to note the analogy that the art critic Rui Mário Gonçalves drew, in the early 1980s, between the artist’s engravings in which she depicts André Malraux and the posters:

“In these works — A poesia está na rua — it is impossible not to recognise faces similar to that of Malraux. For her, and for the intellectuals of her generation, Malraux embodied the international struggle against Iberian fascism. A happy coincidence.”

Indeed, when the revolution happened, Vieira da Silva was in the process of completing a series of engravings in which she portrayed the French writer and critic, André Malraux, and she went straight from this to the posters suggested by Sophia. Coincidentally, the Foundation acquired the five portraits of André Malraux in 1976, which later became part of the Centro de Arte Moderna collection.

The posters proclaiming A poesia está na rua became icons of a historical moment in Portugal, the triumph and celebration of democracy. Vieira da Silva herself wrote: “If I made two posters to celebrate the 25 of April it was because the 25 of April was a historical moment. The end of a war that had lasted 13 years, longer than the Trojan War. And the end of a dictatorship.”

From the Archives

Significant moments in the history of Calouste Gulbenkian and the Gulbenkian Foundation in Portugal and around the world.