Leaving everything behind so as not to lose music

S., J., F., M., S., A., R., S., Z. and S. are all teenage refugees living in Portugal. Asking them how they are is a fruitless exercise, as they always respond that they are “fine”, even when their faces say otherwise, even in those rare moments when they reveal their feelings and their eyes tear up, when they have a ticket in their pocket to leave their new home and school the next day with the intention of going far away and never coming back.

Stoically, they hold the line: they are fine. With the return of the Taliban to power, music has been banned in Afghanistan. One of few mixed schools in the country and the only music school, the ANIM (the Afghan National Institute of Music) has since been occupied and its instruments destroyed. Silence has settled in the centre’s classrooms, corridors, and outdoor space. Silence and fear. Students and teachers lived in fear of retaliation for months. Ahmad Sarmast, the director of ANIM, constantly complained of the panic in which he lived, fearing for the lives of his students on a daily basis.

The process was complex, but students and teachers were eventually rescued with the help of the cellist Yo Yo Ma and the Qatari government. At the end of 2021 they arrived safely in Portugal, with the prospect of seeing their families arrive soon afterwards. The wait in Lisbon was long – too long for teenagers – and their relatives never arrived. Until things started to move. The youngest were received in Braga. Another group was received by the municipality of Guimarães under the Guimarães Acolhe programme. They now live in a new house specially renovated to receive them, a stone’s throw from the Conservatory, where they receive classes with the support of the Gulbenkian Foundation.

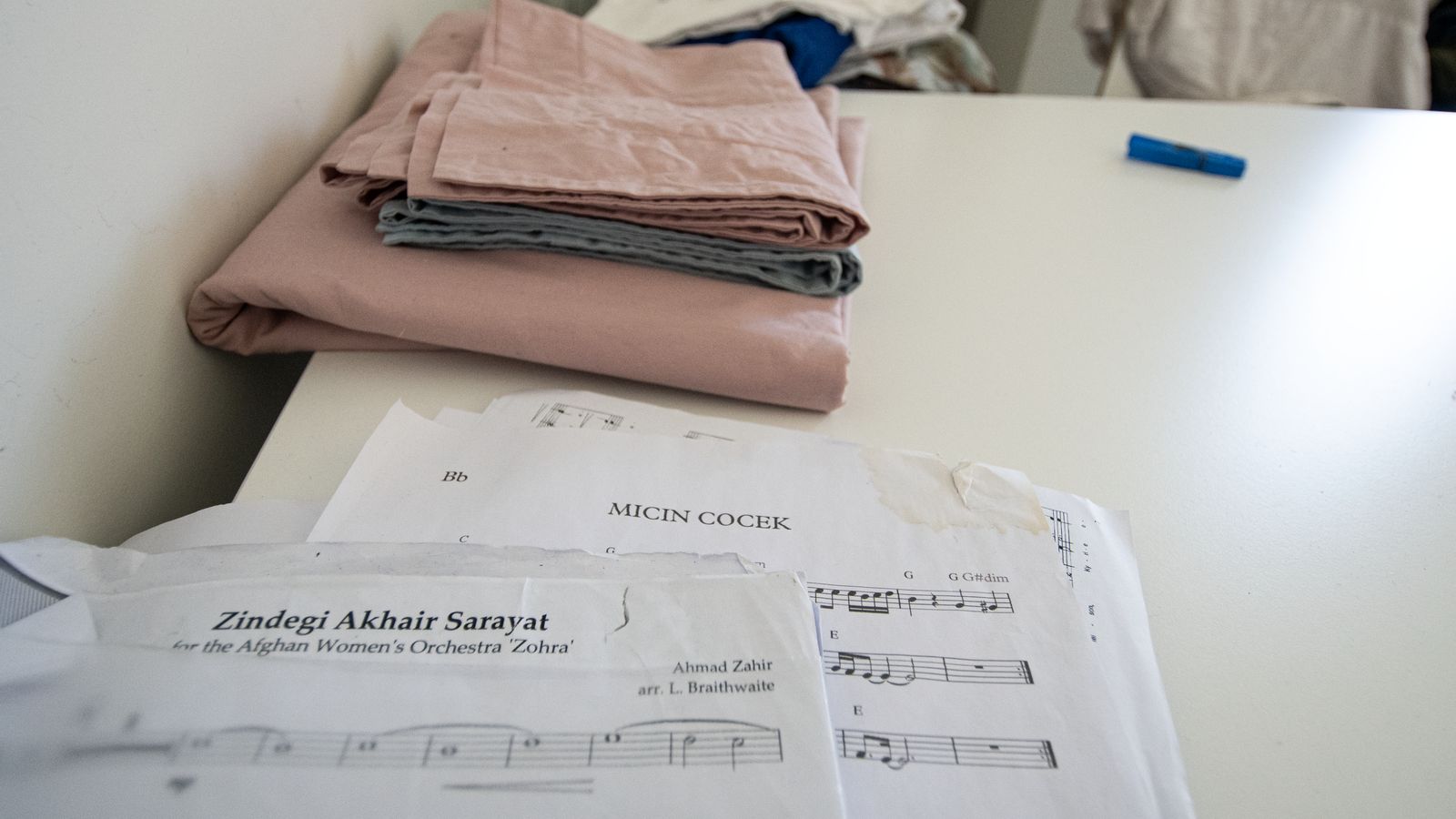

The Foundation’s relationship with ANIM is longstanding, with the Gulbenkian Foundation having supported the Zohra Orchestra, ANIM’s only female ensemble, for several years. A symbol of the emancipation of women in Afghanistan, Zohra has performed at the World Economic Forum in Davos, at the British Museums in London, and, of course, at the Gulbenkian Foundation in September 2018 as part of the Young Musicians Festival. The latter event also included meetings and workshops between members of the Gulbenkian Orchestra and Zohra.

Requested by the High Commissioner for Migration in 2022, the Foundation’s support for Zohra and the ANIM more broadly was welcomed without hesitation. The Foundation supports 10 young people who entered the Guimarães Conservatory of Music to continue their studies.

Aged between 13 and 17, they have a new home and a new school (two, for those attending blended classes). They continue to play in the ANIM orchestras and are accompanied 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, by a dedicated specialist team.

Knowing how to deal with closing doors…

Those who accompany them know that despite their efforts to feel “at home”, it is not easy to live away from one’s family. It’s not easy to communicate in English, let alone Portuguese. It’s not easy to adapt to the routines and habits of Portuguese culture. It’s not easy to keep up with the pace of school, whether at the Francisco de Holanda Secondary School or at the Guimarães Conservatory. It’s not easy to fit in.

One day, 17-year-old A. asked Domingos Castro (the Conservatory’s director) how to make friends. Being paired with members of the Students’ Association could work, thought Domingos Castro, who saw in A. a potential link between two worlds whose boundary was difficult to cross.

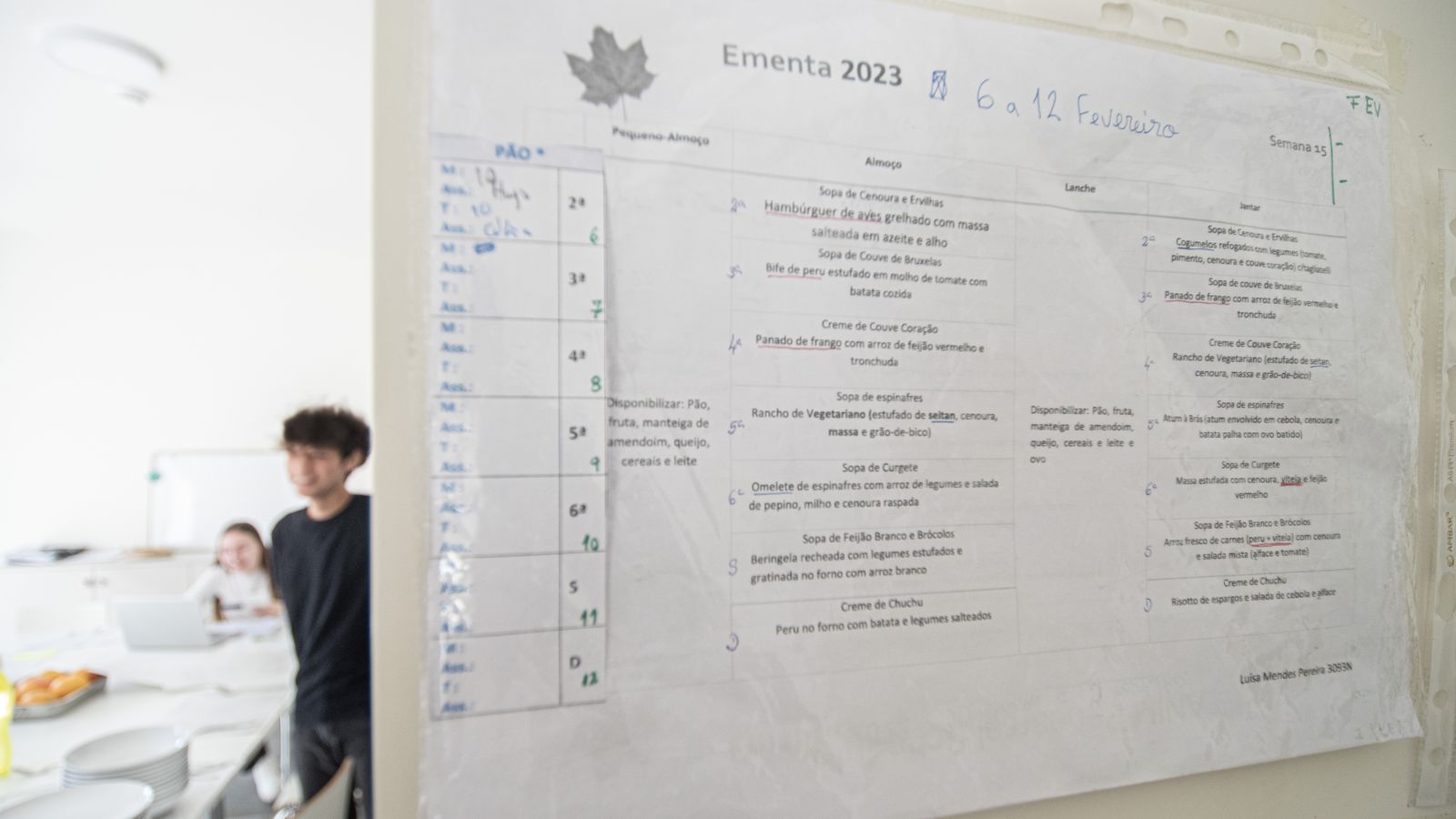

The Students’ Association welcomed the idea, but had problems with the language barrier, the different routines, the absences for everything and anything, the strained relationship between (Portuguese) boys and (Afghan) girls. Being unaccustomed to Portuguese food was a further complication, because they began to have all their meals (by nature a time for socialisation) at home, explains a member of the Students’ Association. It was “very difficult to establish contact, to gain their confidence”, he says. “It was culture shock”, he explains. “It can’t be easy.”

Indeed, before the end of the first semester, many wanted to give up on music – the very thing that had brought them to Portugal from the terror they faced in Afghanistan. Domingos Castro called them one by one. F. confessed that she was motivated by something else – her desire to become a doctor. Measuring his words, Domingos Castro told her that it would be difficult to fulfil that ambition in Portugal. Getting into medicine is difficult enough for Portuguese students, let alone a foreign student who barely speaks English and has difficulty keeping up with all her classes. Faced with the closing door, the director of the Conservatory opened a window: why not music therapy? This would be a good compromise between music and medicine. F. gained new motivation and even volunteered in a Cercigui show. In the same vein, R. wanted to study law, but accepted a suggestion to follow production, an area where she could use the law in her work. Two others dreamed of pursuing computer science and settled for computing and the prospect of making music for computer games.

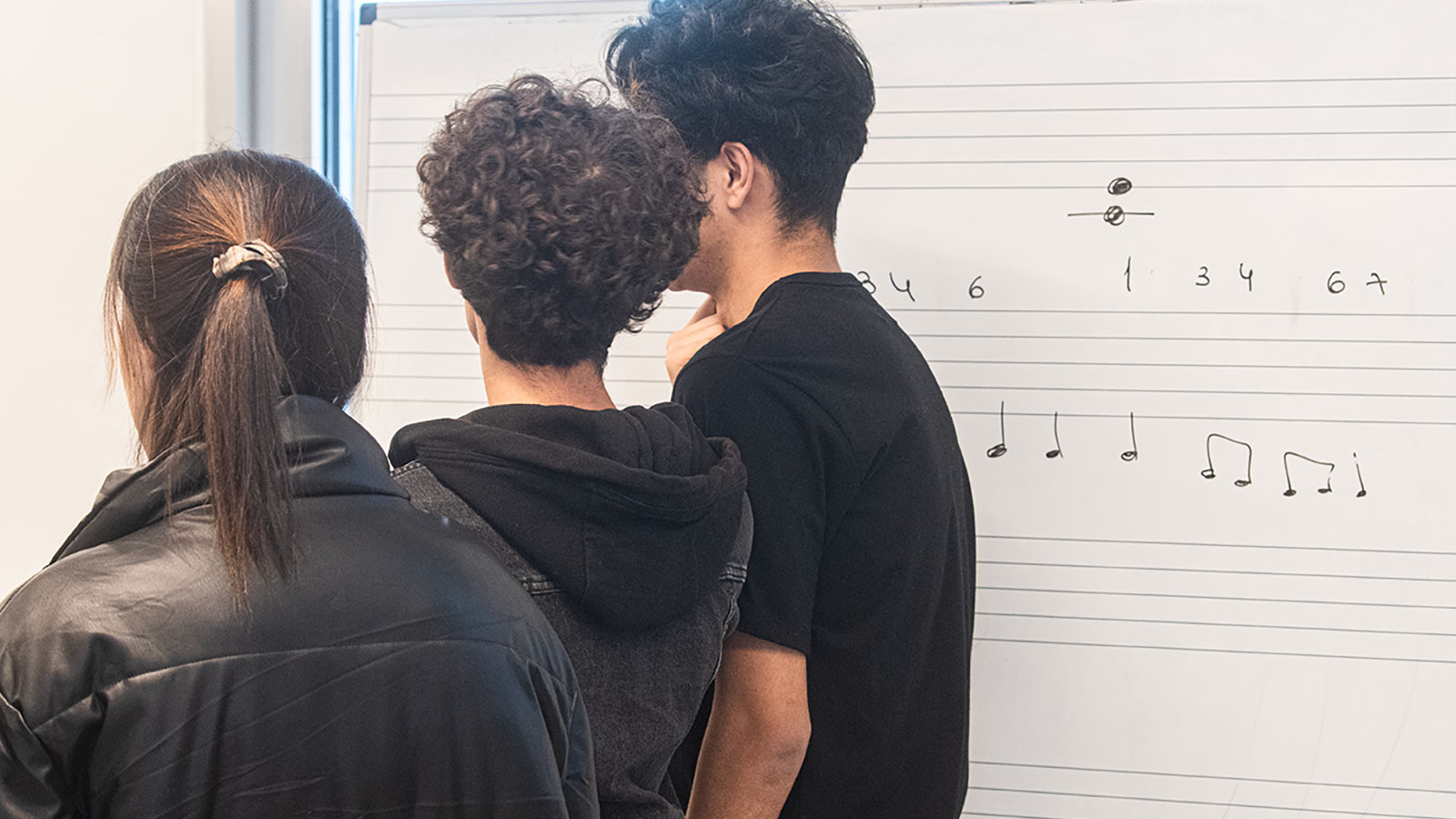

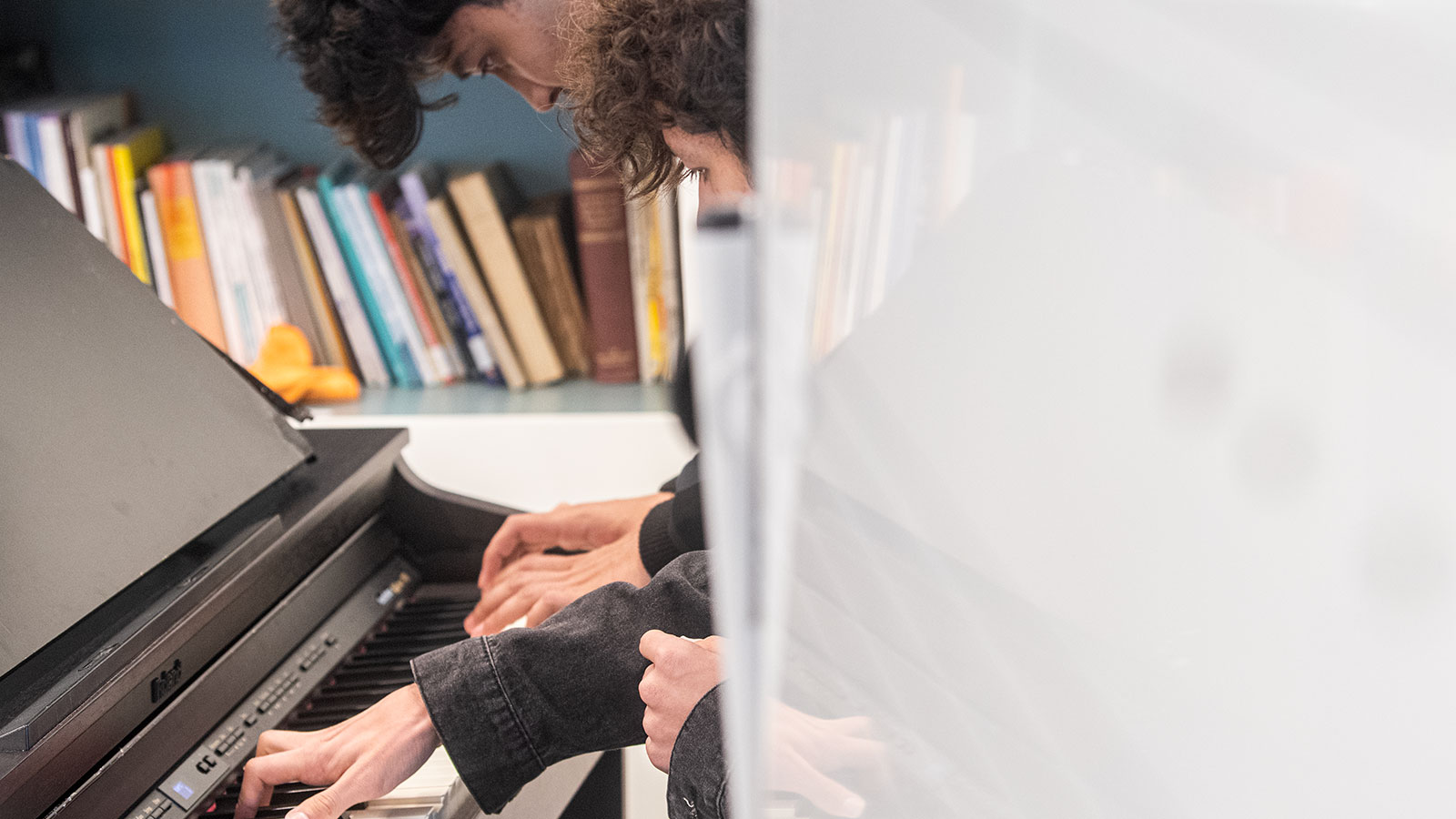

Domingos Castro reviewed everything. Individual instrument lessons were running smoothly and the rest was adapted with changes to curriculum and contents. Now, after some time together in the choir and experimental ensemble classes, everything is flowing better. The barriers are starting to break down.

Shockwaves

Yet the friction is not limited to the outside world. Harmony within the group is not easy either, especially as this group did not know each other in Afghanistan. Despite the closeness of their ages, they are not all friends – they are colleagues. And not everyone thinks or views their new life in the same way.

A. thinks that many of his colleagues do not take their new life seriously enough. What pains him the most is that his sister, S., is wasting the opportunity that was given to her. His other three sisters in Afghanistan can’t even go to school.

The house includes one student who maintains the veil during Ramadan and another who wants to be an influencer. There are those who play traditional instruments and those who dream of becoming a pop star. In the kitchen and at the table everything goes well, but the group classes were very complicated at first. The boys would go, but the girls’ attendance was somewhat patchy. Physical education classes or going to the swimming pool was a nightmare. Boys and girls had to be separated, because no matter how westernised their minds may be becoming, they don’t accept showing their bodies to each other and don’t accept doing so in front of their compatriots. Their connection to their roots is strong.

Concern for those left behind is also strongly felt. They try by all means to send money back home, where there is no work. One of the younger students tried to send home €500 for his family (the money he received from the State to create a nest egg in order to become independent later on). The older ones, now around 18, only ask for help to find part-time work.

At the conservatory as at home, everything is done to help make them feel good. They are colleagues not family, says M. through Laleh Esteki, the Iranian who works with the High Commission for Migration and visits them at least once a week, but “the support workers are like family.” While they wait for the arrival of their families to Portugal, as promised, all they have is each other.

She has a sister working as a teacher in the United States and her boyfriend, also from ANIM, is now in Canada. It’s a whole world that could open up for her. And go back to Afghanistan? M. doesn’t hesitate: “Yes, but only without the Taliban! Who wouldn’t want to go back?”

For more on the ANIM students’ departure from Afghanistan in August 2021, see the report Symphony of Courage by Voice of America.