Duplicata

This proposal for an imaginary exhibition brings together works from the collection that can be read as having a dual structure, a sharing, a division, replication or form of symmetry.

As a backdrop, I refer to Plotinus’ theory, according to which conscience is an unfolding, reflection, or flexion of the self, a fold, a projection of the number two, of the distance the division creates between subject and object when the One expresses and manifests itself. I find works that allow me to expand on and observe the concept in diverse ways:

the striking scenographic nature of works by Noé Sendas and Noronha da Costa, in the lighting they demand, in their direct reference to theatrical characters, to shadows, masks and doubles.

Bruno Pacheco, Daniel Blaufuks, Isabel Simões, Armando Ferraz, Ana Jotta, Alexandre Estrela, Lourdes Castro, Waltércio Caldas, Fernando Lemos and Jorge Molder also expressing different forms of duality: verbal, reproductive, spatial, relational, graphic, photographic and structural.

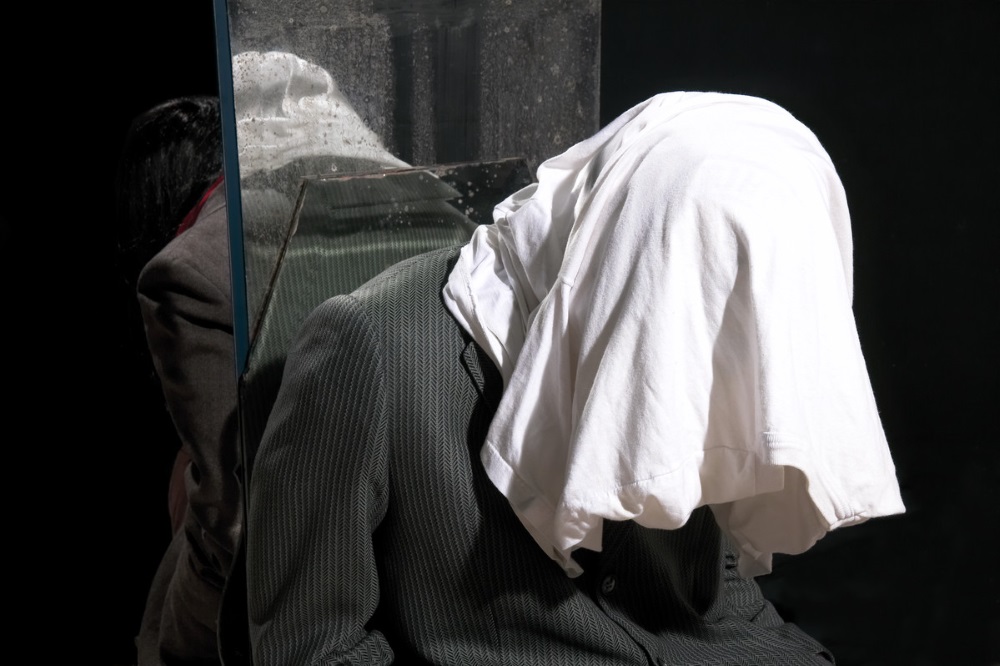

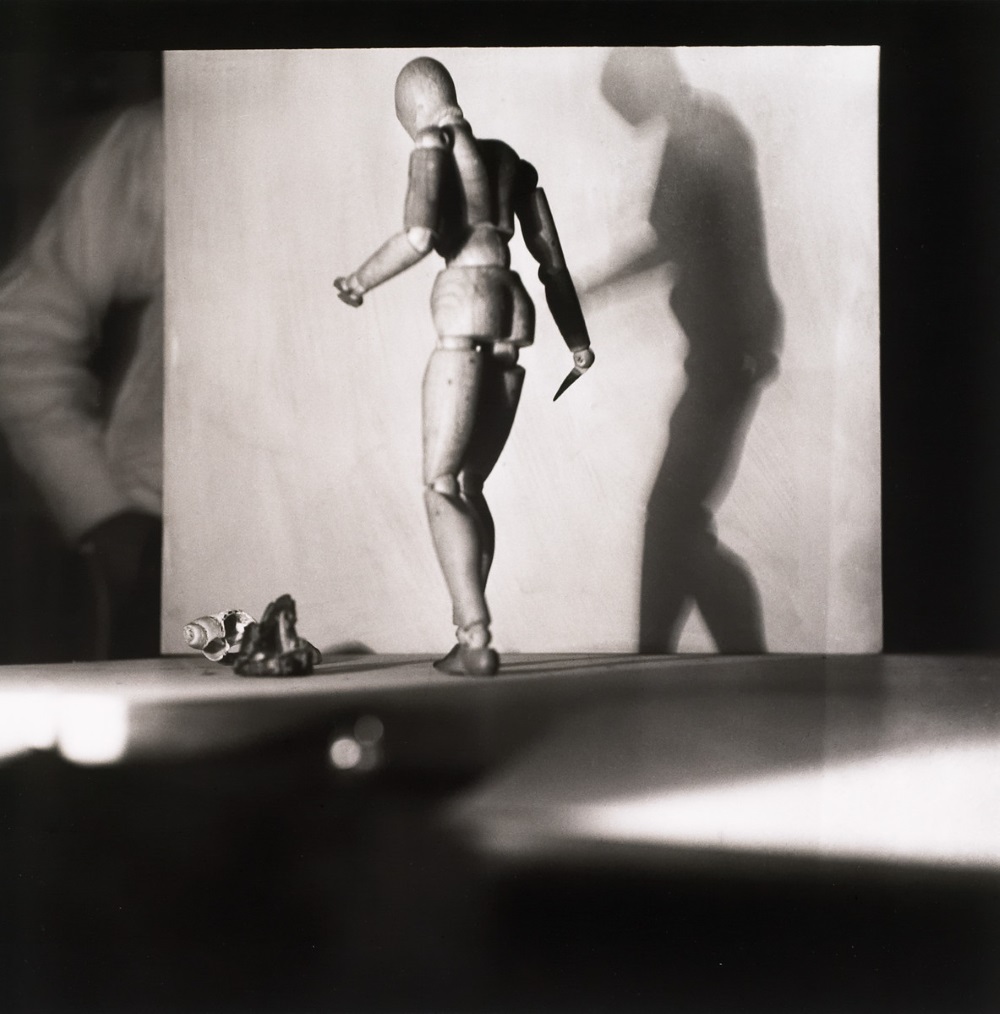

With Noé Sendas, we are confronted with the twin condition of mannequins, backs turned to each other, the incommunicability, silence and solitude of two beings very close to one another. The dropped head introduces an essential dissonance: it choreographs sleep, death or submission. Separating them, a double-faced mirror sends each figure to its respective place, making communication even more remote as a possibility. Mirrors, spaces and characters insist on the redundancy of this separation. Symmetry and visual duplicity can metaphorically allude to a single, split individual, dramatically cleaved within themselves.

Noronha da Costa’s installation keeps us in the imaginary place of threshold and shadows, a limbo in which life and death switch places. The screen and the idea of a search for nature, or for the essence of the image, which underlies it (and underlies all his work), is the central element. In this work and in others from the same period (1967–69), the screen has the unique particularity of being viewable from its two sides.

The head we see, a mask that can be associated with the Greek proscenium, is no more than a mark without identity, a deposit, a mortal remain, a vague vanitas, a spectre fluctuating in the haze of the screen, which is also a kind of translucency of the grave. The candles make the image emerge; almost religiously they light the ‘stage’ of this scene, the narrative of this altar. In 1978, the artist wrote that the blue in the piece isn’t colour: it is distance. The blue of many of his works, and which is mentioned in this title, does not live here; only in the eternal memory of the Mediterranean as a classical, dramatic and dramaturgical cultural reminiscence.

Bruno Pacheco’s device is simple but surprising: from inside a 45º angle, two words move alternately towards the edge of two screens – ‘Hello’ and ‘Goodbye’. It makes us think of Autocue on television, but from the point of view of professionals and not from the perspective of the viewer, which is our usual position. The almost imperceptible labial – or perhaps just mental – connection between the two words places us in an empty world, with only beginning and end, arrival and departure, with no other narrative. This word that is barely there, the most summary greeting of those who meet or take their leave, is also a metonym for the encounter between the viewer and a work, when no more than a glimpse is provided. There is something diabolical in this ‘robot’ elevated to the status of man, in its silence, in the mechanisation of its minimal vocabulary, as though language, in its grandeur, had been switched off on some deep level.

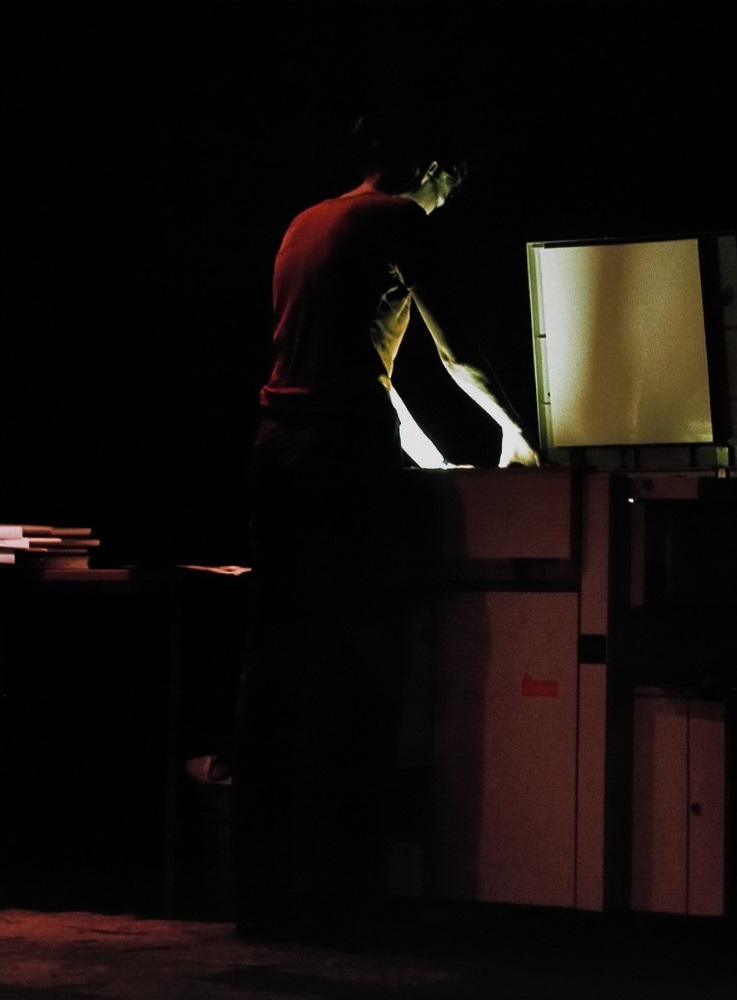

The intimacy and expectation created between a person and a machine are central to this diptych by Daniel Blaufuks. We think about the labour of creating images: those arms appear outstretched as though plunging into a photographic developing tray. The low-angle perspective exaggerates the heroine of this act without importance. In the archive room, the central figures are light, alignment, the series, the underlying reproductive principle, the stifling silence, the serious feel of the place. We can imagine the silent and intransmissible enjoyment of the books and documents. The diptych emphasises this encounter, formed of intermittent absence and presence.

The painting by Isabel Simões is, perhaps, the only work in this group that doesn’t show duality or duplication in an obvious way. Isabel Simões paints an architectural detail: a vent at the top of a wall that makes us think of the reality of a closed precinct with restricted circulation of air. This side, and the other that we can’t see, the exterior that makes breathing possible inside, and the filter, which also makes life audible outside, form the essential, somewhat anguished, mode of the duality projected here. The title, Quero ouvir-te respirar [I want to hear you breathe], introduces this bridge between subject and object, which defines our condition in the world.

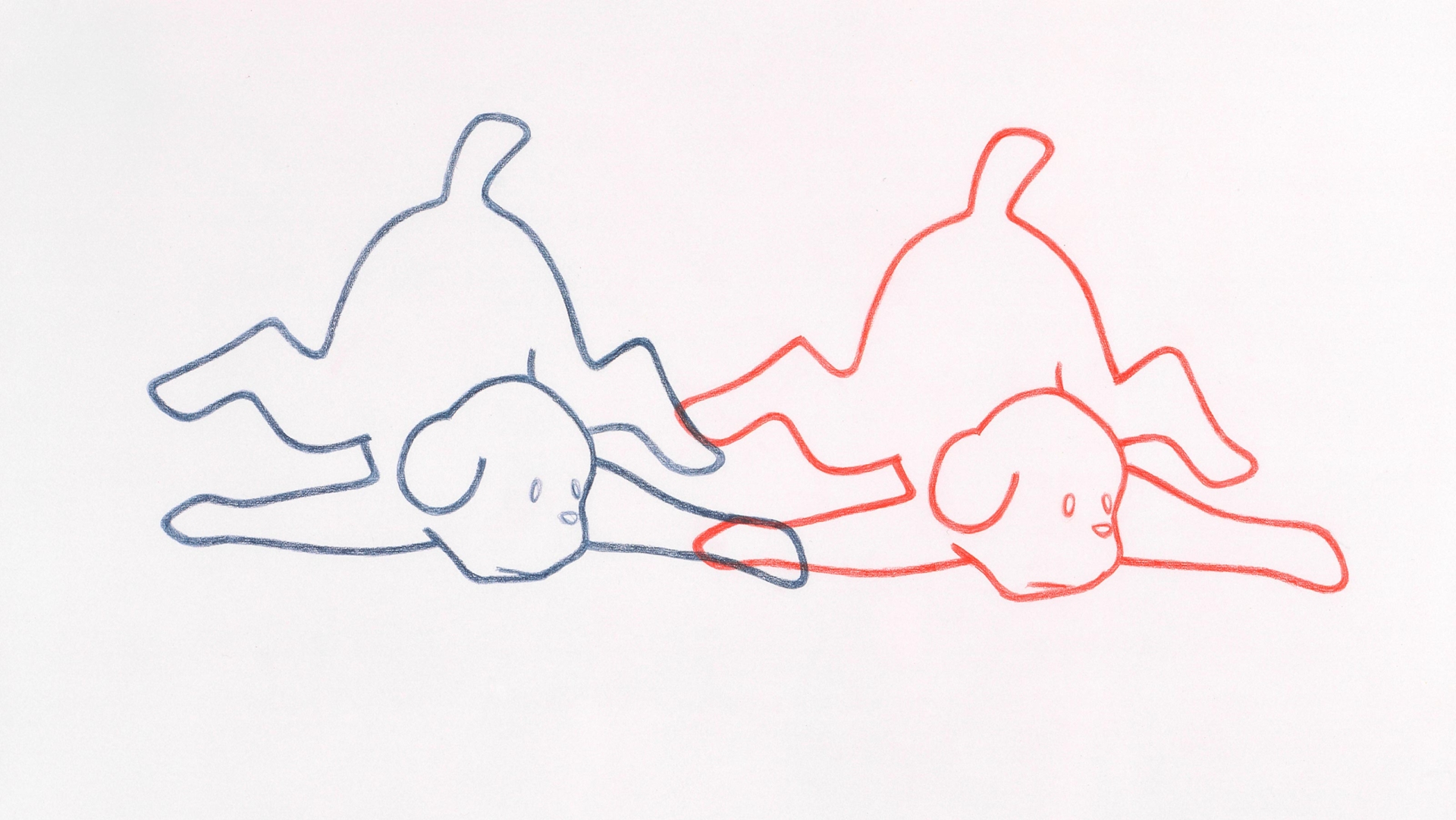

Mockery and playful challenge, always appreciable in Ana Jotta’s work, are expressed in a drawing that shows the simple graphic duplication, in another colour, of the minimalist outline of a dog, flattened and with legs splayed – a possible cartoon – and in the drawing embroidered on the cloth of the roller towel system entitled ‘Roger’: two young children, a boy and a girl, innocently investigating their respective anatomical differences.

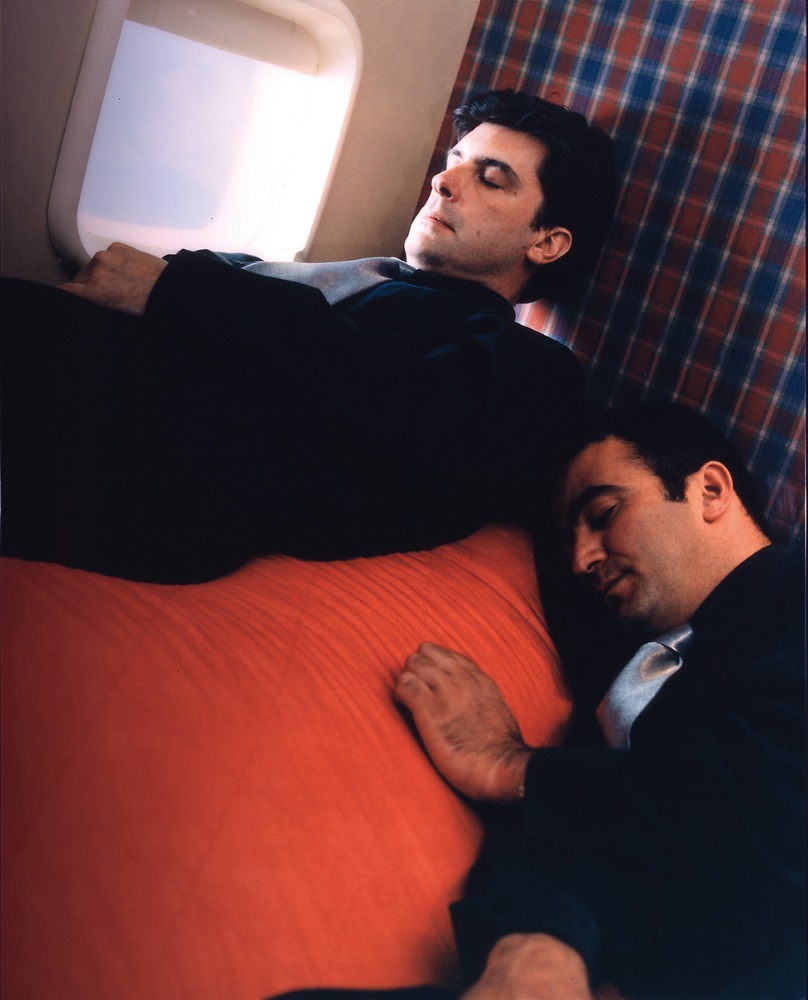

In Armando Ferraz’s photograph, the bright colours of the décor and the black of the two figures provide an effective contrast. The sleep they share in a tiny space is one disturbed by that of the other. Adding to this difficulty is the diagonal orientation of their position, which renders even more fragile the territorial demarcation of the sleep of each of the figures.

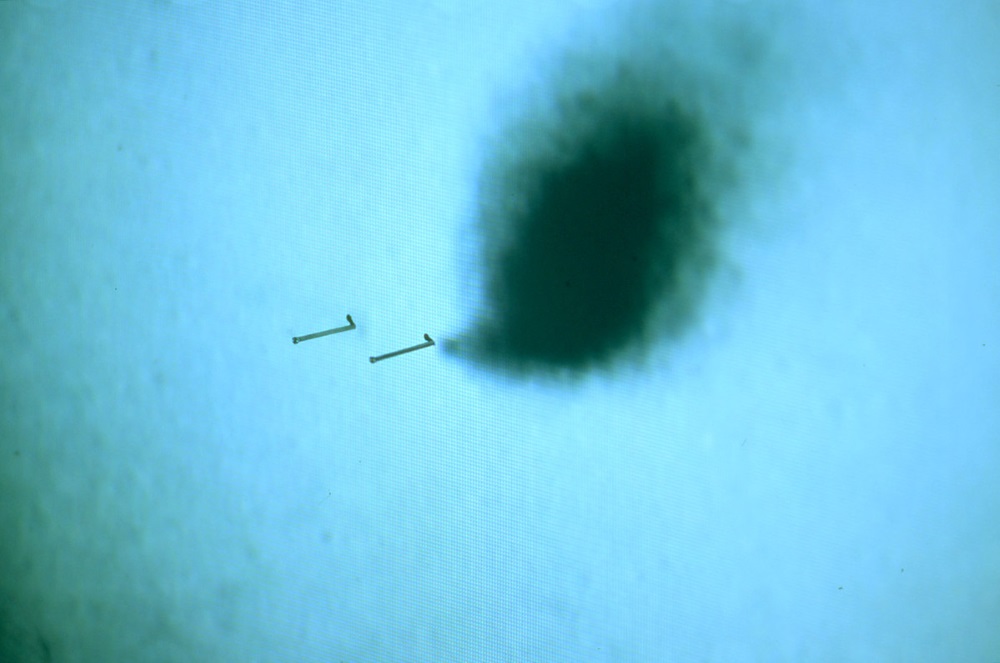

In Alexandre Estrela’s installation, we are presented with an unexpected double. At the point where two nails meet the wall, clouds of smoke steadily billow out, launched into the imaginary atmosphere provided by the vast space of a white wall. The knowledge that it is the repeated feedback of the image of the nail itself that causes the effect (passage from a solid to gaseous state, in a continuum that starts with a metal nail that appears to be dissolving into smoke or issuing it) reinforces a notion of consubstantiality: everything emerges from the same source material.

During the 1960s, Lourdes Castro created micro-scenes on plexiglass, like this In the café, in which the gestures of two figures are suspended in the succinctly evoked space of a table in a café. Instead of their ‘shadows,’ or silhouettes, Lourdes Castro defined white, luminous surfaces, thus bringing to life the empathy of the encounter.

Waltercio Caldas carved into painted metal the exclamation of all scientists – ‘EUREKA!’ – and placed the word in reverse in front of a mirror, in which we can also see our own face, equating language with being or putting it in the place of being: the metaphor of a psychic inclination, in which the observer plunges into the visual and mental effect of what they find written on its surface. The structure of mirrors in Caldas’ work is the mark of an almost immaterial physicality, in which the space for thought and lines of force of the objects dissolve into one another to suggest movement and opening to the expanded experience of reproduction, duality and duplication.

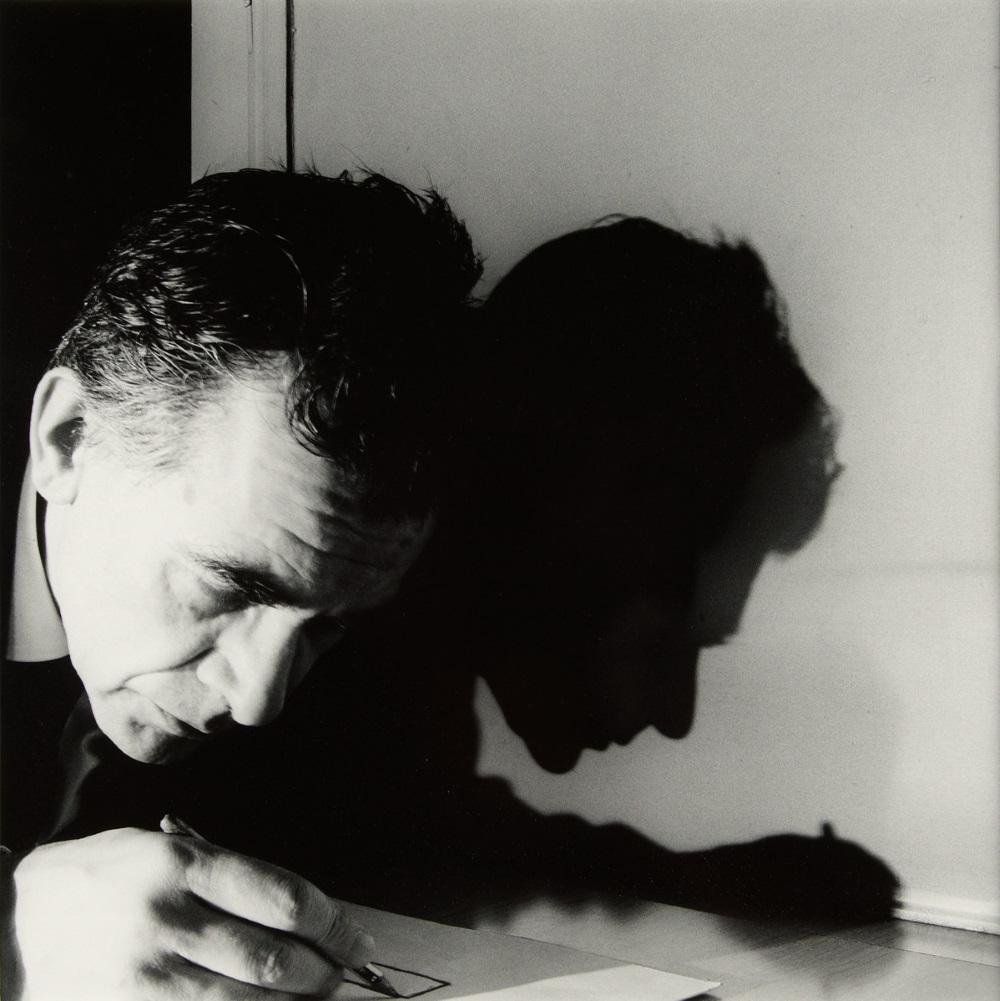

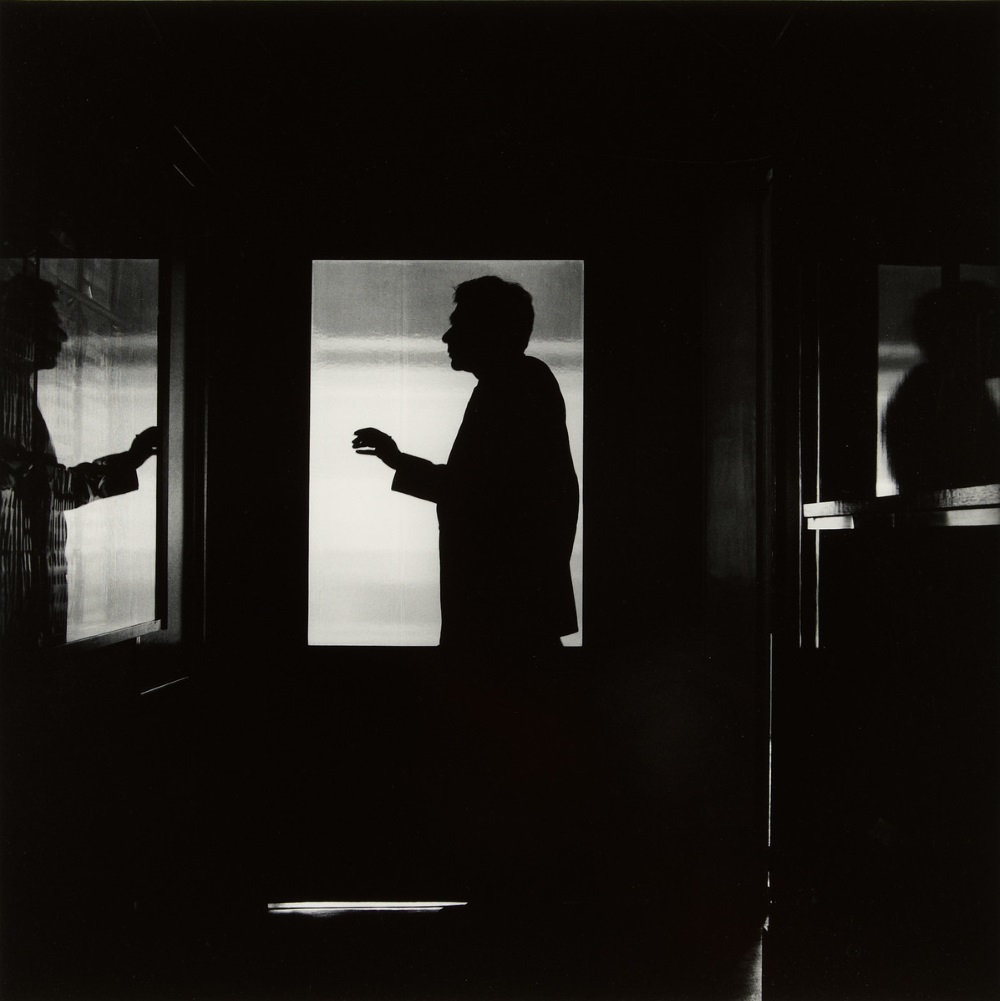

In one of the photographs by Jorge Molder, the concepts of mirror, glass, door, screen, window and place of image coincide in the circumscription of the place of the figure, who is facing himself. The walls are kept in the half-light so that the appearance of the figure always cleaves a place in the light, the profile and hands frequently betraying restlessness and surprise. Focusing on a precise gesture of writing or drawing, another of the images shows the face coming very close to the paper, the torso curving over it as if poring over a precious map. A shadow theatre duplicates the figure on the adjacent wall, giving it the dramatic depth of a moment of supreme creativity and secrecy. In the photograph from ‘Não tem que me contar seja o que for’ [You don’t have to tell me whatever it is], a series of 31 different films giving rise to 32 images, the classic image of a happy couple is based on Louis Malle’s Ascenseur pour l’échafaud [Elevator to the Gallows], 1958. ‘These photographs are cinema,’ wrote Bénard da Costa.

Fernando Lemos joins a long tradition of great dreamers, in the multiple meanings the word takes on in designating respect for and fascination with the night and the unconscious, as well as daytime exaltation, utopia, creation, art, freedom of spirit and the fullness of humanity. In the two photographs from the series that made him famous in Portugal (taken between 1949 and 1952), and which I have selected here, Lemos creates the effect of a double by repeating the shot over negatives. In another image, he uses a simple device of projecting shadow.

Double and shadow are inscribed in a long and dense literary and legendary tradition that could continue propelling us, over time, towards a conclusion and an openness about the meaning of this Duplicate (imaginary exhibition).