Construction of the Iraq-Mediterranean oil pipeline

Constructed by the Mediterranean Pipe-Lines Limited, a subsidiary of the Iraq Petroleum Company Limited (IPC), between 1932 and 1934, the Iraq-Mediterranean pipeline was originally envisaged in an Agreement signed on 14 March 1925 between the then Turkish Petroleum Company Limited (TPC), the predecessor of Iraq Petroleum Company Limited, and the Iraqi government, in the context of the exclusive concession granted to the company to explore for, produce and export oil in the country’s territory.

Geologists started to explore and prospect for oil in October that year, in five teams covering the concession territory.

Drilling started in April 1927 and oil was struck in October that year, gushing from a well in Baba Gurgur, in the vicinity of Kirkuk.

The success of this well, and the exceptionally abundant crude resources it yielded, showed up the weaknesses in the system for producing and then transporting the oil. An oil pipeline was urgently needed, and this project was prioritised over extraction efforts.

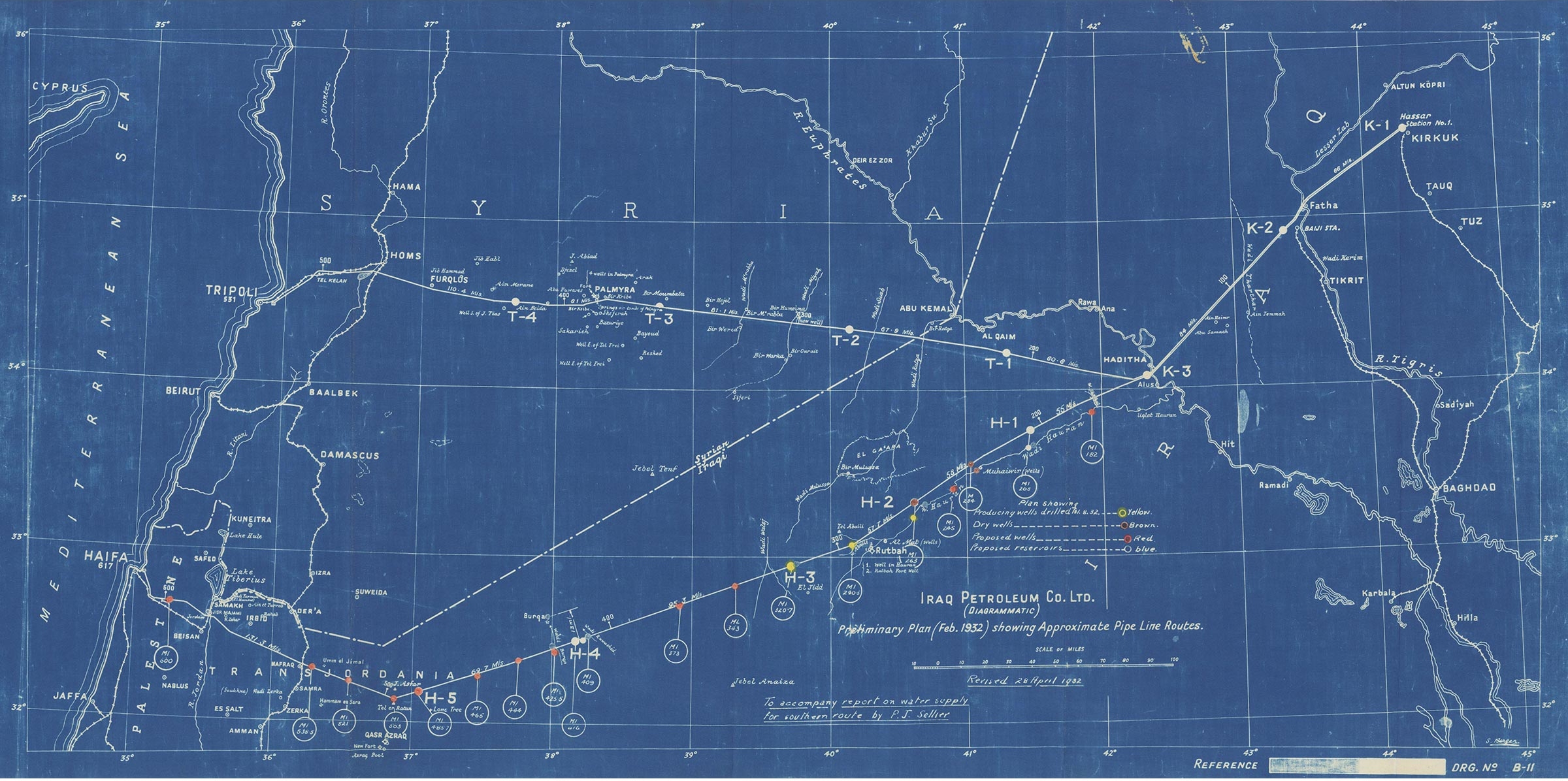

Surveying work started in January 1928. The company opened a small office in Beirut in mid-1929, joining those already functioning in Baghdad and Kirkuk. The new office handled all the operations concerning the future pipeline, and possible routes, to the north and to the south, were being studied by the end of that year.

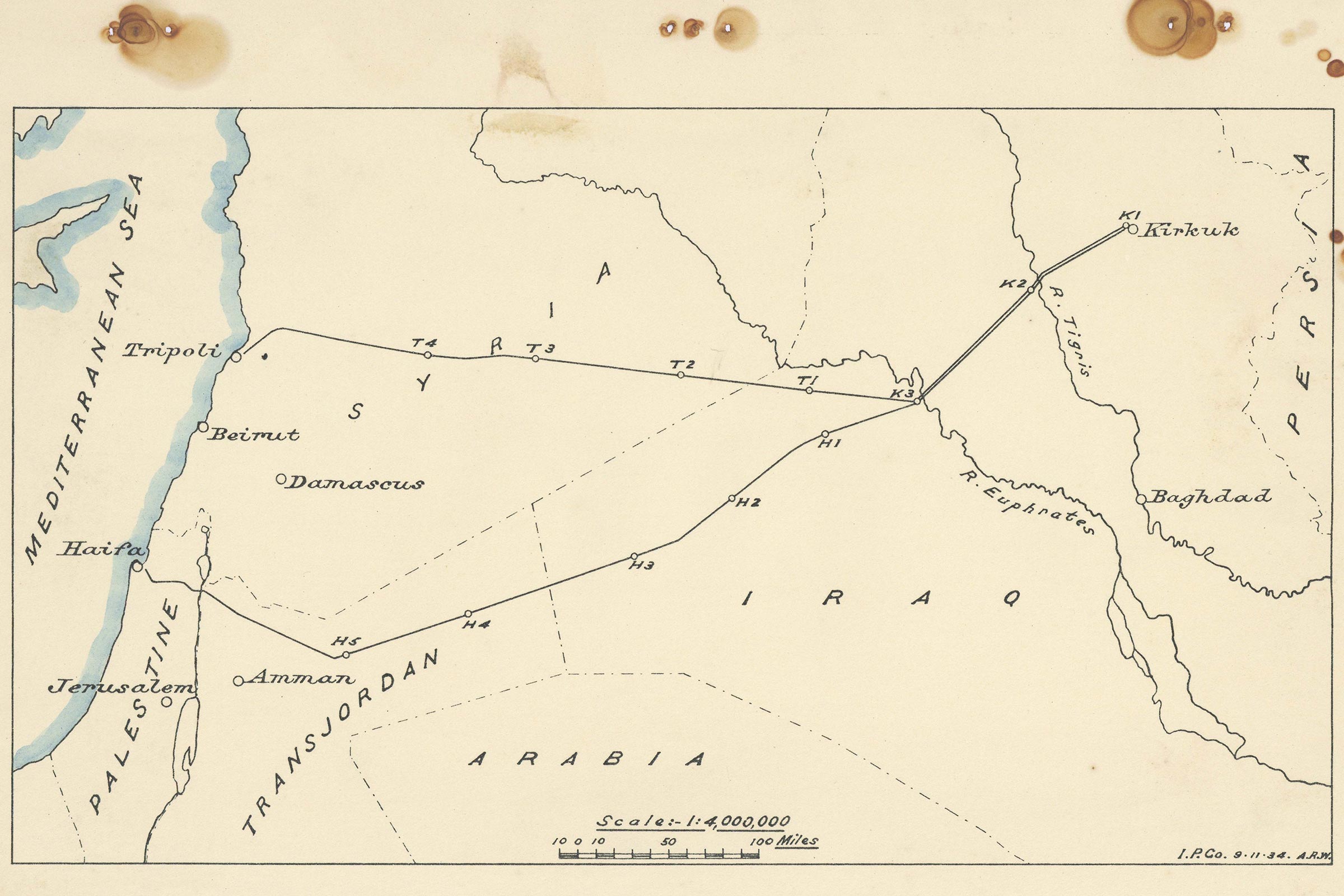

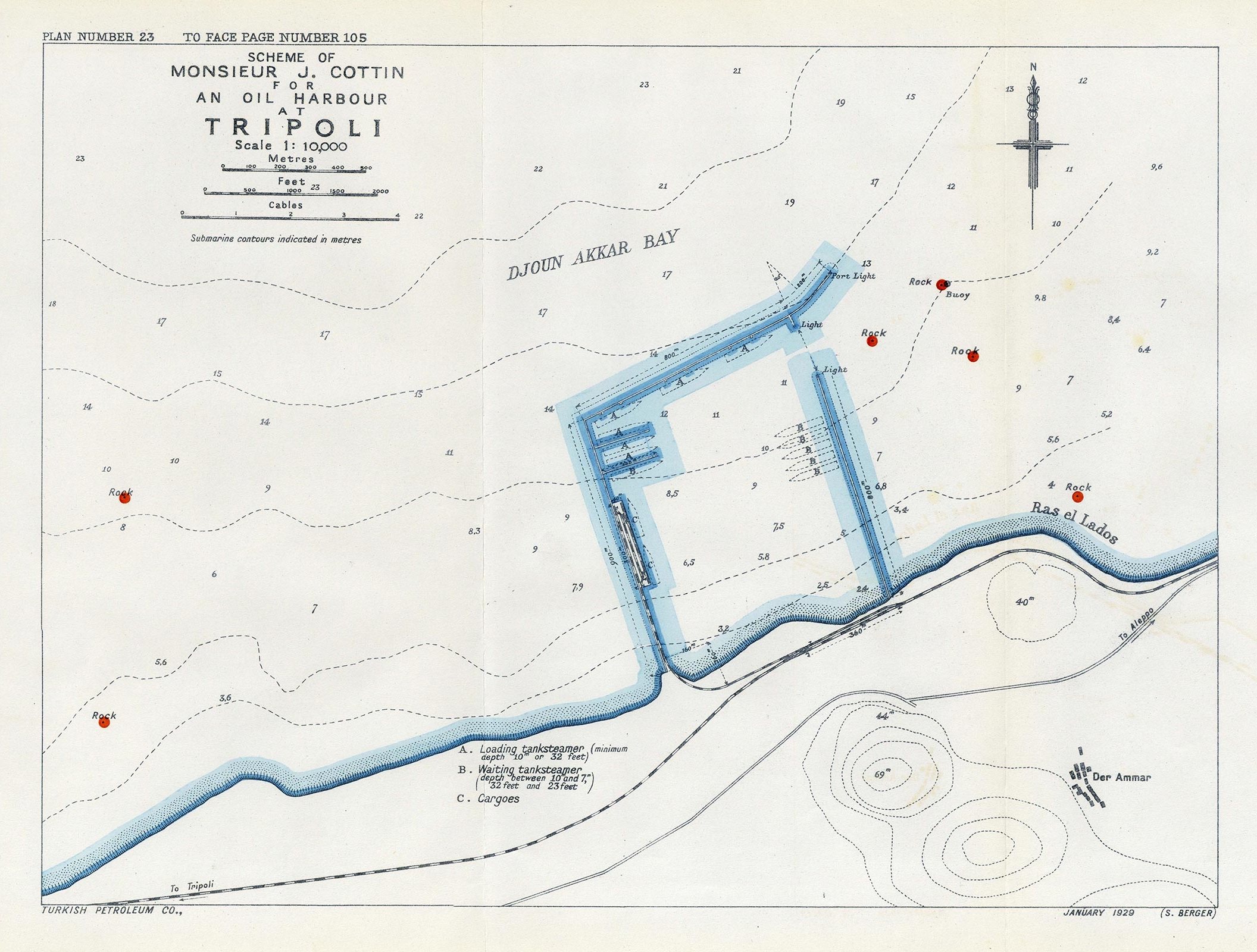

It was definitively decided the following year that the pipeline would divide in two in the vicinity of Haditha, one line taking a more northerly route through Syria and Lebanon and reaching the Mediterranean in Tripoli, and the other continuing southwards, through Trans-Jordan and Palestine, ending in Haifa.

As Nubar Gulbenkian records in his autobiography, this decision was hotly “(…) debated between the various investors in I.P.C. (…) On purely financial grounds, it was obvious that the pipeline should follow the shortest and safest route to the sea, and that meant heading for Tripoli (…).

However, this meant crossing territory under the French mandate, and so being subject to French control, which, for political and commercial reasons, worked for the French and, for purely commercial reasons, worked for us [the Gulbenkian].

But it did not work for the British investors, who wanted to route the pipeline through Palestinian territory under the British mandate, ending in Haifa. (…) Neither side appeared willing to back down, until another way out of the impasse was found (…). On the suggestion of one of the Americans, it was agreed there would be two pipelines”.

More detailed plans for the two lines were drawn up at the end of that year. The oil pipeline project gained further momentum with the new agreement between what was now Iraq Petroleum Company Limited and the Iraqi government on 24 March 1931.

Agreements were reached in the meantime with the governments of Palestine (January 5, 1931), Trans-Jordan (January 11, 1931), Lebanon (March 25, 1931) and Syria (March 25, 1931), allowing for the pipeline to traverse these territories.

The world’s first transnational oil pipeline was on its way to becoming a reality.

Work started on staking out the route in the middle of that year. The Iraq Petroleum Company Limited opened new offices in Haifa, Amman, and Tripoli.

In order to handle matters relating to the pipeline, the Iraq Petroleum Company Limited set up an advisory body, the Pipe-Line Committee, as well as a subsidiary company, the Mediterranean Pipe-Lines Limited. Nubar played an active role in both, representing his father.

Gulbenkian had already delegated matters relating to his holding in Iraq Petroleum Company Limited to his son, and to Kevork Essayan, his son-in-law.

Mediterranean Pipe-Lines Limited took charge of building the oil pipeline. As early as 1932, contracts were signed between Iraq Petroleum Company Limited and its subsidiary, transferring the right to build, own and use the oil pipeline (February 19, 1932), as well as for the actual construction work (March 11, 1932).

The completion date for the work was set at 31 December 1935.

The construction work proceeded from 1932 to 1934. Starting from Kirkuk, the route was staked out through the Al-Fatha Gorge as far as Haditha, close to the banks of the Euphrates, where it forked into two lines. From this point, the northern line was routed through Al-Qaim and then Palmyra and Homs, and finally on to the terminal in Tripoli. The southern line proceeded to Muhaiwir, and from there via Rutbah, Um-el-Jemal and Jisr al Majami to the terminal in Haifa.

It was regarded as the most ambitious engineering project of its time, and also the most costly – “The most expensive chicken in history”, as Nubar dubbed it – in the midst of a global economic depression. The Iraq-Mediterranean oil pipeline was able to transport four million tons of petroleum a year, through steel piping with a diameter of 12 inches (reduced to 10 and 8 inches at certain points along the route).

Twelve pumping stations kept the oil moving along the pipeline. In addition to this primary function, the pumping stations also served to monitor the quantity and quality of the liquid flow, as well as providing a base for repair and maintenance work on the pipeline.

From Kirkuk to where it forked at Haditha, the pipeline had three pumping stations – K1 to K3. After dividing at Haditha, the northern line, to Tripoli, had four stations (T1 to T4), whilst the line running south to Haifa had five (H1 to H5).

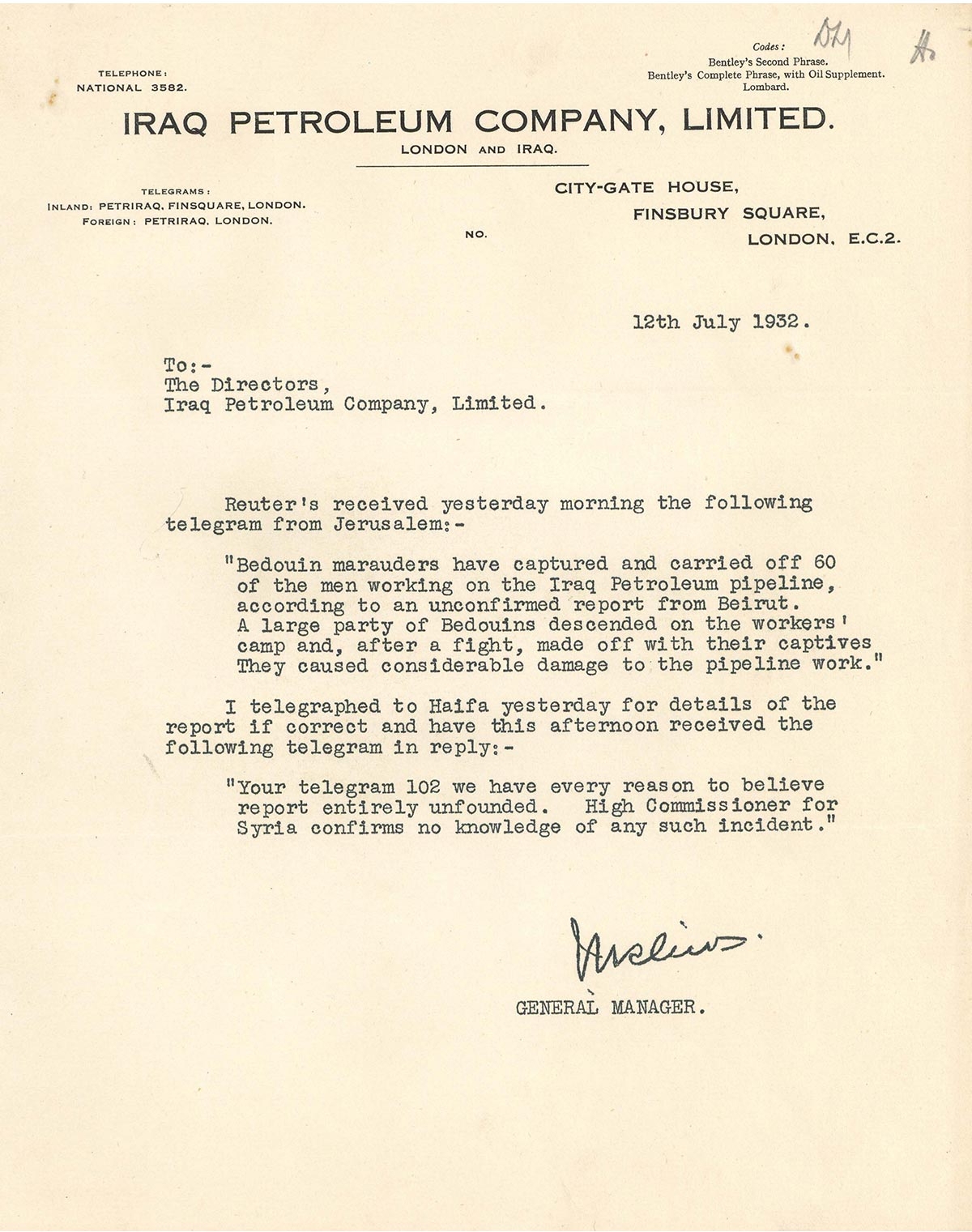

All of them with fortress-like defences. On this point, Nubar recorded: “I spent the night at one of the pumping stations which, surrounded by high walls, looked for all the world like a fort (…), indeed, all of the pumping stations were built in the same way, to withstand possible Bedouin attacks.”

Nubar also records some of his impressions of the construction work on the pipeline, when the project was in full swing: “In the spring of 1933 I travelled to the Middle East to keep an eye on Iraq Petroleum Company and its operations. (…) The main work under way was the construction of parallel pipelines to transport petroleum (…). One of the most notable aspects of the work on the pipeline was the energy and enthusiasm that everyone put into the task. (…) As we drove past, I could see how the oil pipeline was being built. First, there were groups welding lengths of piping to each other (…). Then we saw the diggers, carving a continuous trench into the desert, leaving mounds of earth alongside it. After this, there was a machine that wrapped the pipeline in what looked like giant rolls of toilet paper; these rolls were made from tar paper and their purpose was to stop the pipes from rusting. Then another machine hoisted the pipeline into the trench, where it was then buried under the mounds of earth which were returned to the trench.”

On his journey to Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, in 1934, Calouste Gulbenkian stopped off briefly in Haifa after leaving Beirut, recording in his diary entry for 13 February: “(…) I arrived at the I.P.C. offices in Haifa. Before entering the city, I caught sight of the I.P.C. pipeline, but saw little of it; it was all buried underground. I climbed (…) Mount Carmel to get a general view of the port and the Company’s various facilities: I saw very little: a port like any other, plots of land, some buildings.”

Completed more than a year ahead of schedule, the oil pipeline, comprising the piping itself, the pumping stations, maritime terminals and all the supporting infrastructures needed for it to function, represented a total cost, at the time, close to the planned investment of one million pounds sterling, funded by Iraq Petroleum Company Limited through its shareholders.

The first oil reached Haifa on 16 October 1934.

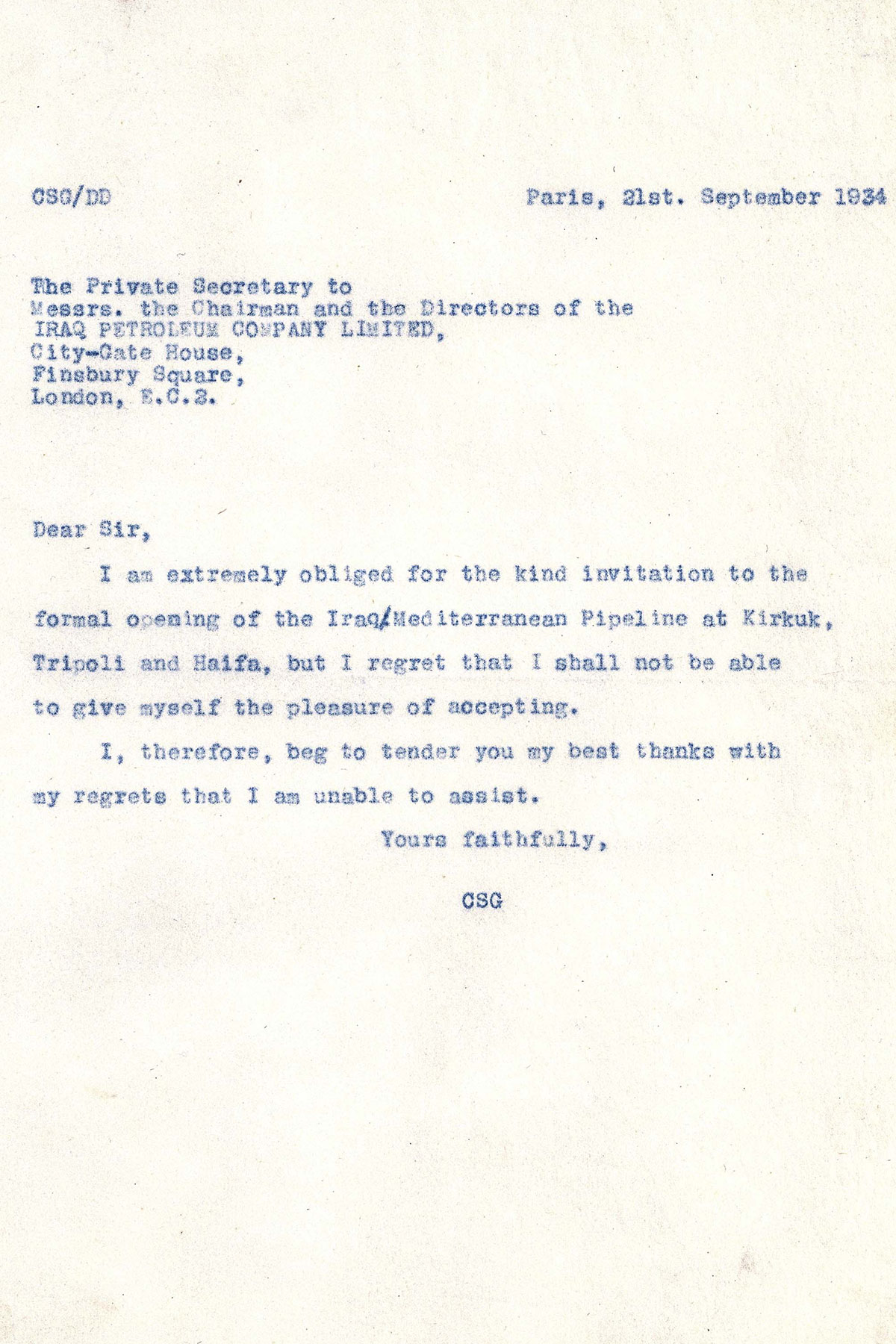

The ceremonies for the official opening started to be planned the following month. Invitations were sent out to leading figures; travel arrangements were made and accommodation secured for guests.

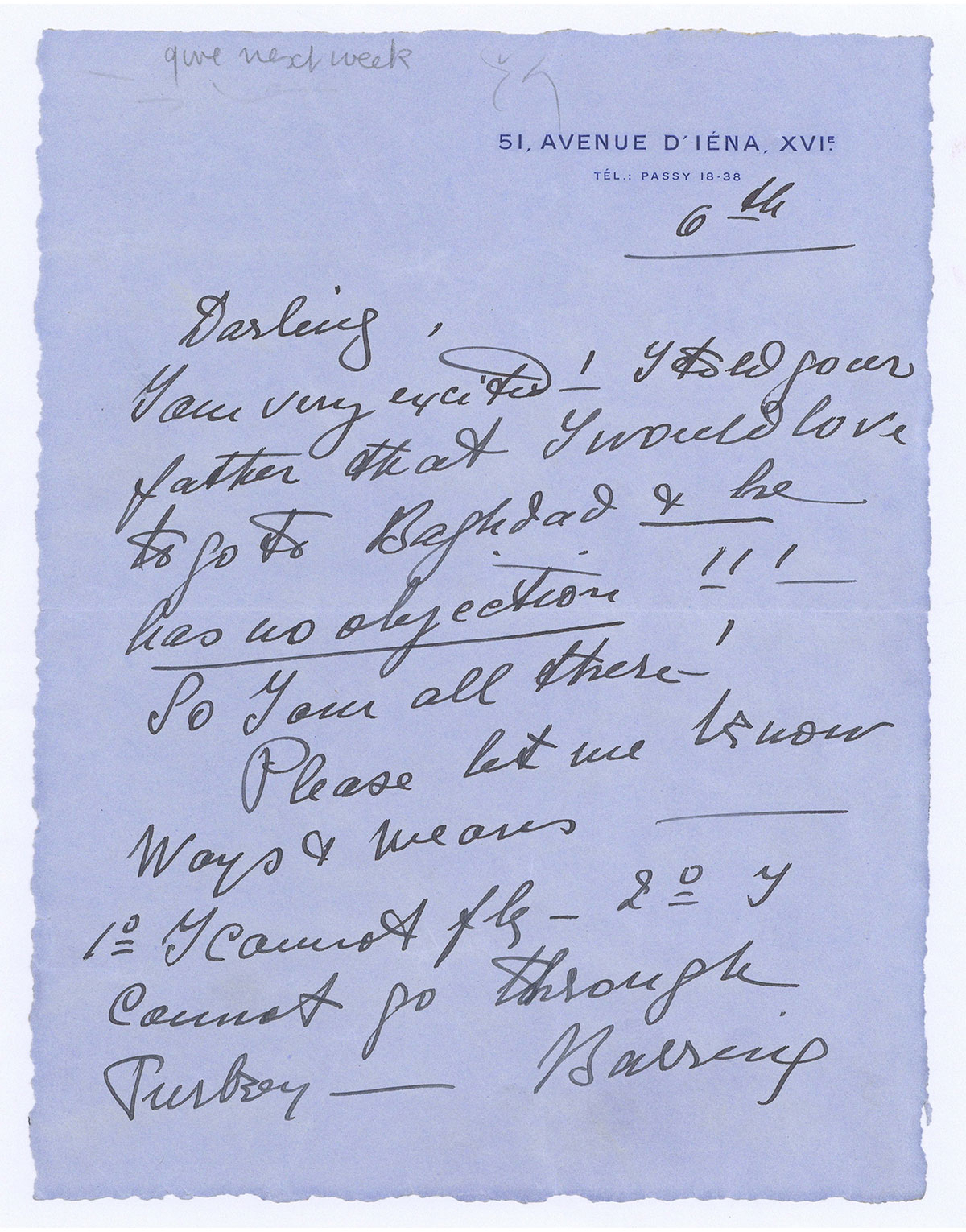

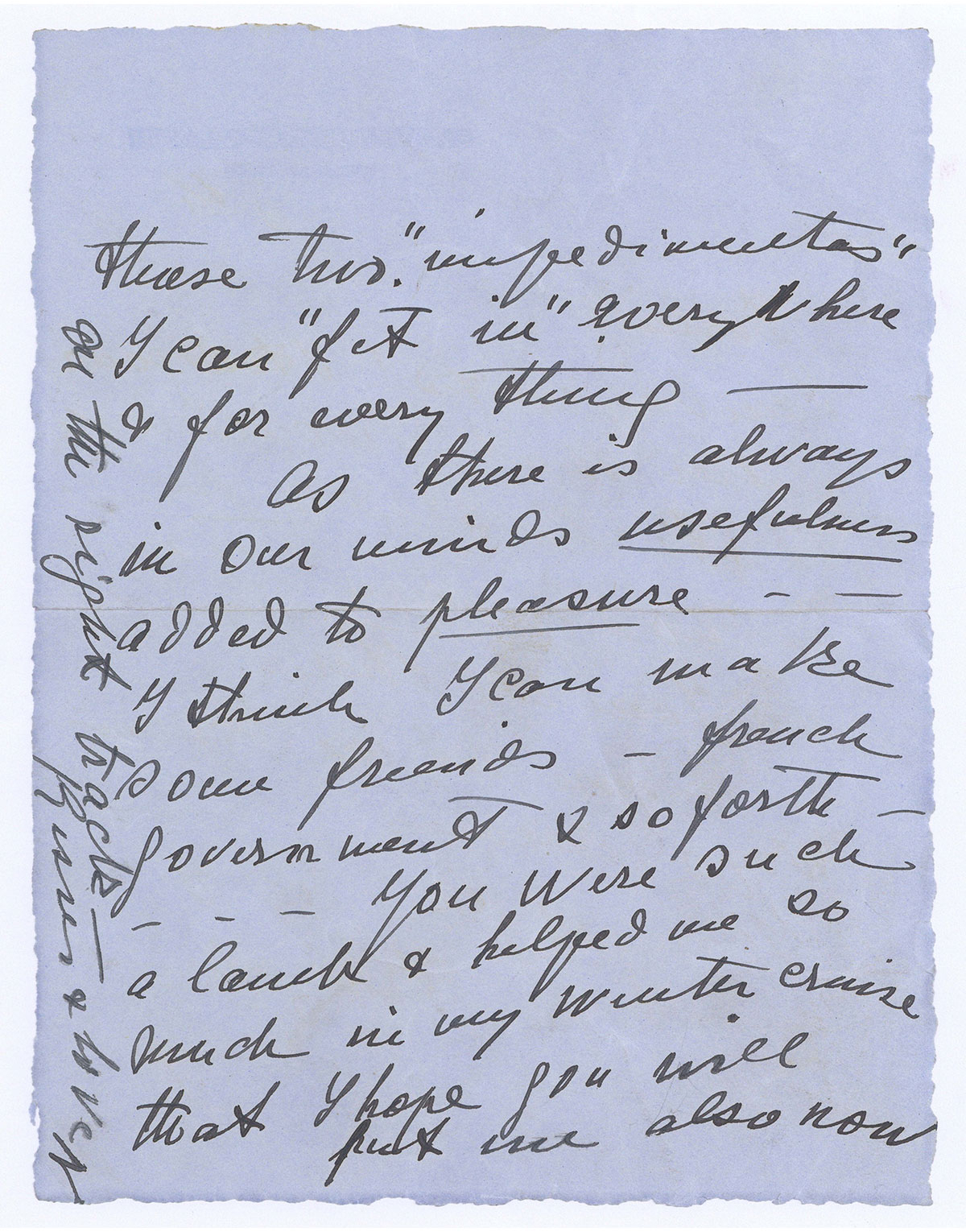

Calouste Gulbenkian declined the invitation to attend the ceremonies. Representing the family’s interests, Nevarte, Calouste’s wife, travelled to the Middle East, accompanied by her brother, Yervant Essayan: “Darling, I’m full of excitement! I told your father I would love to go to Baghdad. He makes no objection!” she writes, enthusiastically to her son, Nubar, on 6 November.

Nubar had decided not to accompany his mother on this long journey, but still helped her to plan it.

The Iraq Petroleum Company Limited had informed Nubar of concerns relating to ladies planning to travel to Baghdad, due to the vagaries of the climate and the poor accommodation at the hotel.

Days before setting out, Nevarte was advised by the company that ladies were not authorised to travel from Baghdad to Kirkuk to attend the opening ceremonies and would have to stay in Baghdad.

The Iraq Petroleum Company Limited cited no special reasons for this restriction other than the lack of accommodation on the aircraft to transport them.

Even so, Nevarte and Yervant set out from Marseille on 4 January on board the steamer Sibajak, reaching Port Said, in Egypt, on the seventh. The next day, they embarked on the train to Jerusalem, where they arrived on the eleventh.

Guests had been gathering in Jerusalem, from 9 to 11 January, from where they departed for Baghdad. Nevarte ended up staying in Jerusalem in the company of the Waley Cohen family and her brother Yervant, without travelling further.

The opening ceremonies took place from 14 to 24 January in Kirkuk, Damascus, Homs, Trípoli and Amman, attended by senior officials of the IPC and leading political and diplomatic figures in the Middle East.

The oil pipeline operated from 1935 to 1948, despite occasional attacks by Bedouin groups.

Its strategic importance in the Second World War is undeniable, especially for supplying Allied forces operating in the Mediterranean. Thereafter, the pipeline’s importance gradually faded, due to political instability in the region.

In 1948, the Iraqi government stopped sending petroleum to Haifa. Over subsequent decades, conflicts built up between the government and the Iraq Petroleum Company Limited, leading, in 1972, to nationalisation of the Iraqi oil industry.

From the Archives

Significant moments in the history of Calouste Gulbenkian and the Gulbenkian Foundation in Portugal and around the world.