Calouste Gulbenkian and “Japonisme”

Although the Portuguese established the first contacts with the empire of the rising sun in 1543 and, in the following centuries, Dutch merchants were allowed to maintain some commercial activities, until 1854, the year of the Kanagawa Treaty – signed with the United States – Japan lived centuries of voluntary isolation.

Four years later, a new treaty – the Treaty of Friendship and Commerce – definitively opened the Japanese ports to the exterior, giving origin to a kind of “rediscovery” and enchantment with Japan and its culture.

This interest in Far Eastern art in the West began to develop as early as the 16th century, largely due to the trade in Chinese porcelains, silks and lacquerware that reached European markets, and extended to architecture and gardens in the 18th century.

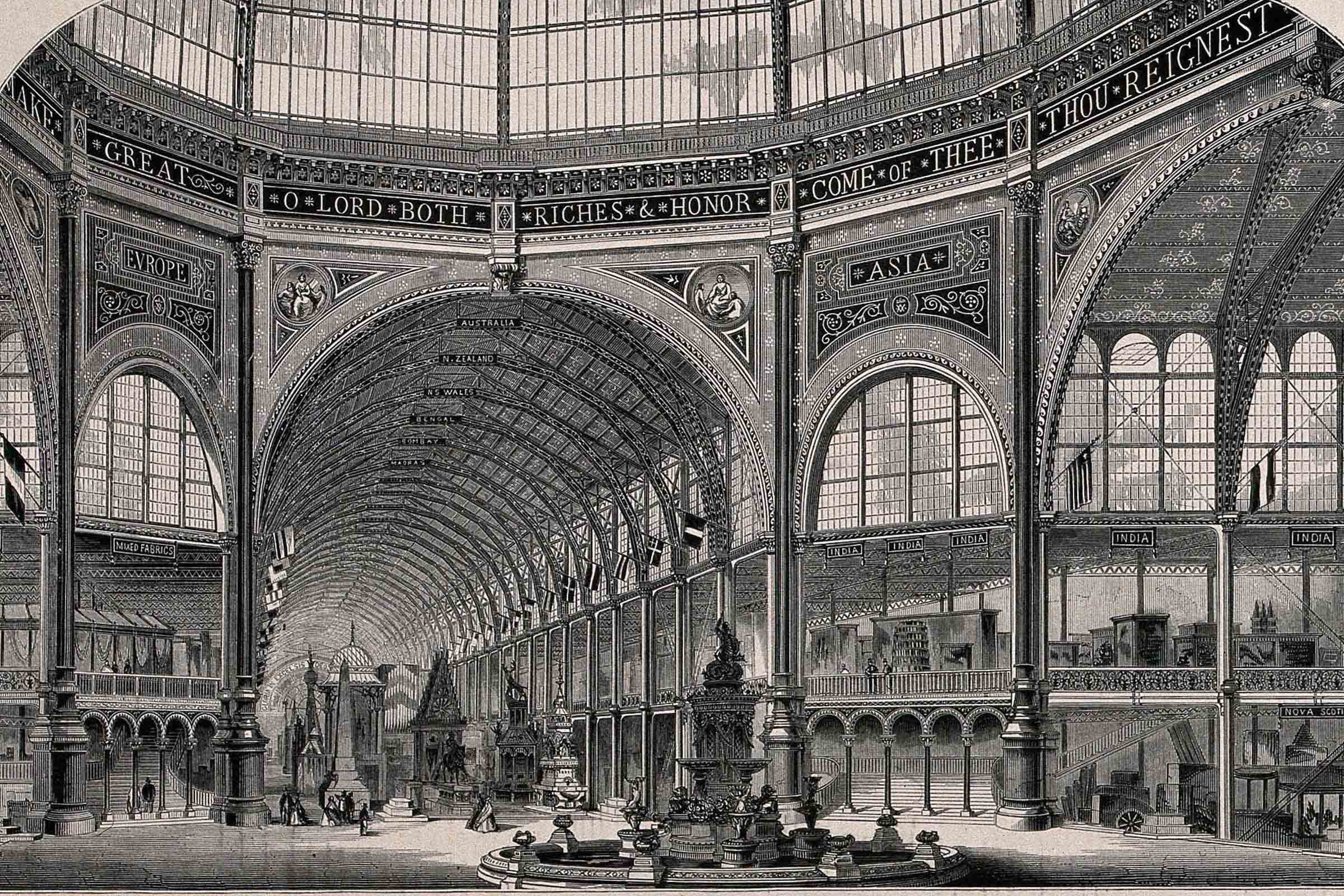

In the following century, the Universal Exhibitions, which inaugurated in 1851 in London’s Crystal Palace, helped to rapidly disseminate this taste for Japanese arts and culture to the Western public and turn it into a fashion.

Japonisme – a term created by the French critic, collector, and printer Philippe Burty (1830-1890) in the early 1870s to designate the influence that Japanese art had on the works of Western artists in the last decades of the 19th century – imposed itself and gained influence at the exhibitions of 1862 (London) and 1867 (Paris).

At the latter, Japan participated for the first time with a pavilion, where visitors could admire various examples of Japanese art. During these years, there were a few shops in the French capital that not only sold various Japanese artistic objects – fans, kimonos, bronzes, lacquers, prints – but also acted as meeting places for artists and collectors of the time.

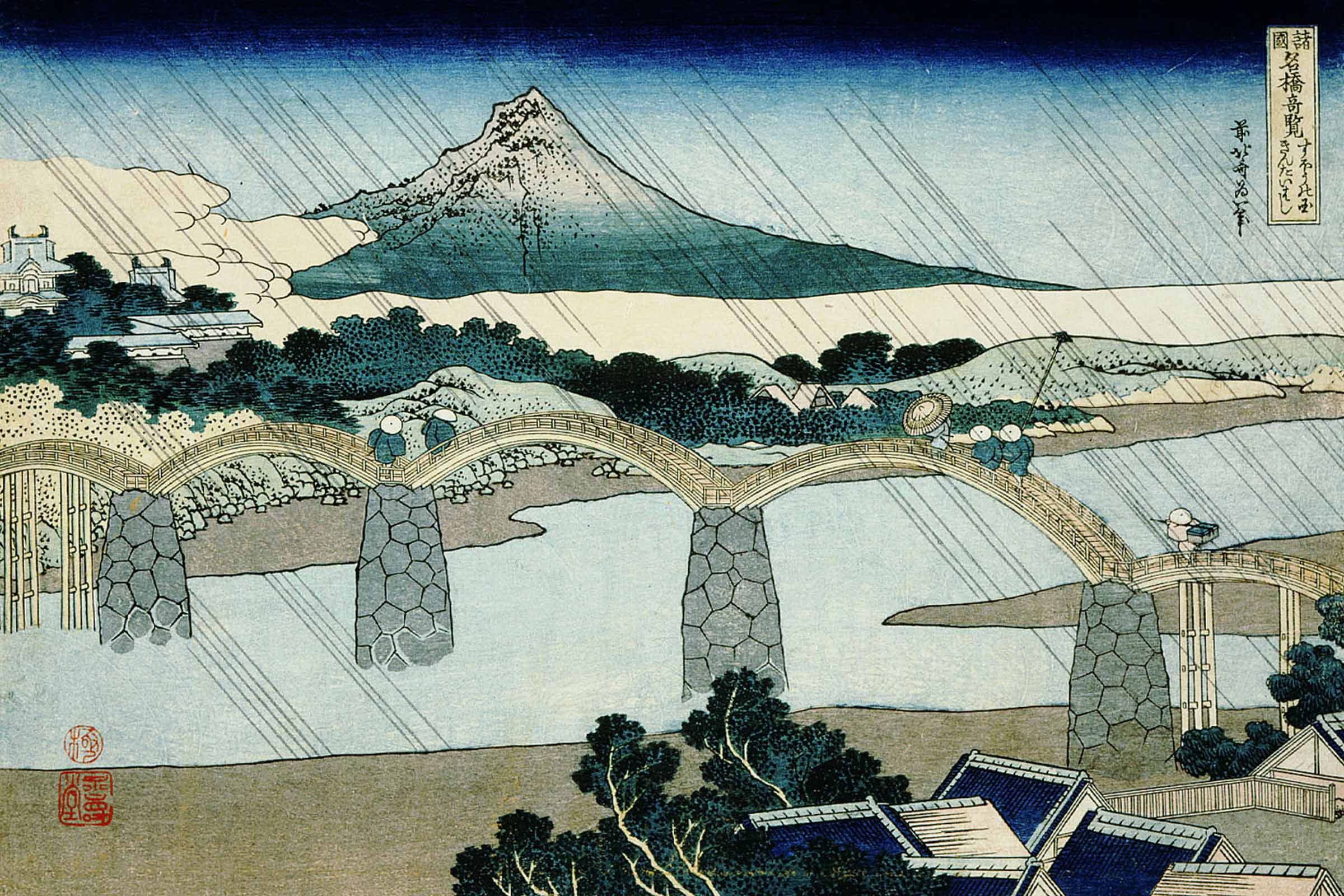

The aesthetic particularities of Japanese art, wonderfully expressed in the prints of great masters like Hokusai (1760-1849) and Utamaro (?-1806), attracted impressionist and post-impressionist painters. Édouard Manet, James McNeill Whistler, Edgar Degasy, and Vincent Van Gogh are among the first collectors of Japanese prints. They were, like Mary Cassatt, Pierre Bonnard, and Toulouse-Lautrec, some of the artists who, influenced by these characteristics, came to incorporate them in different ways into their pictorial production.

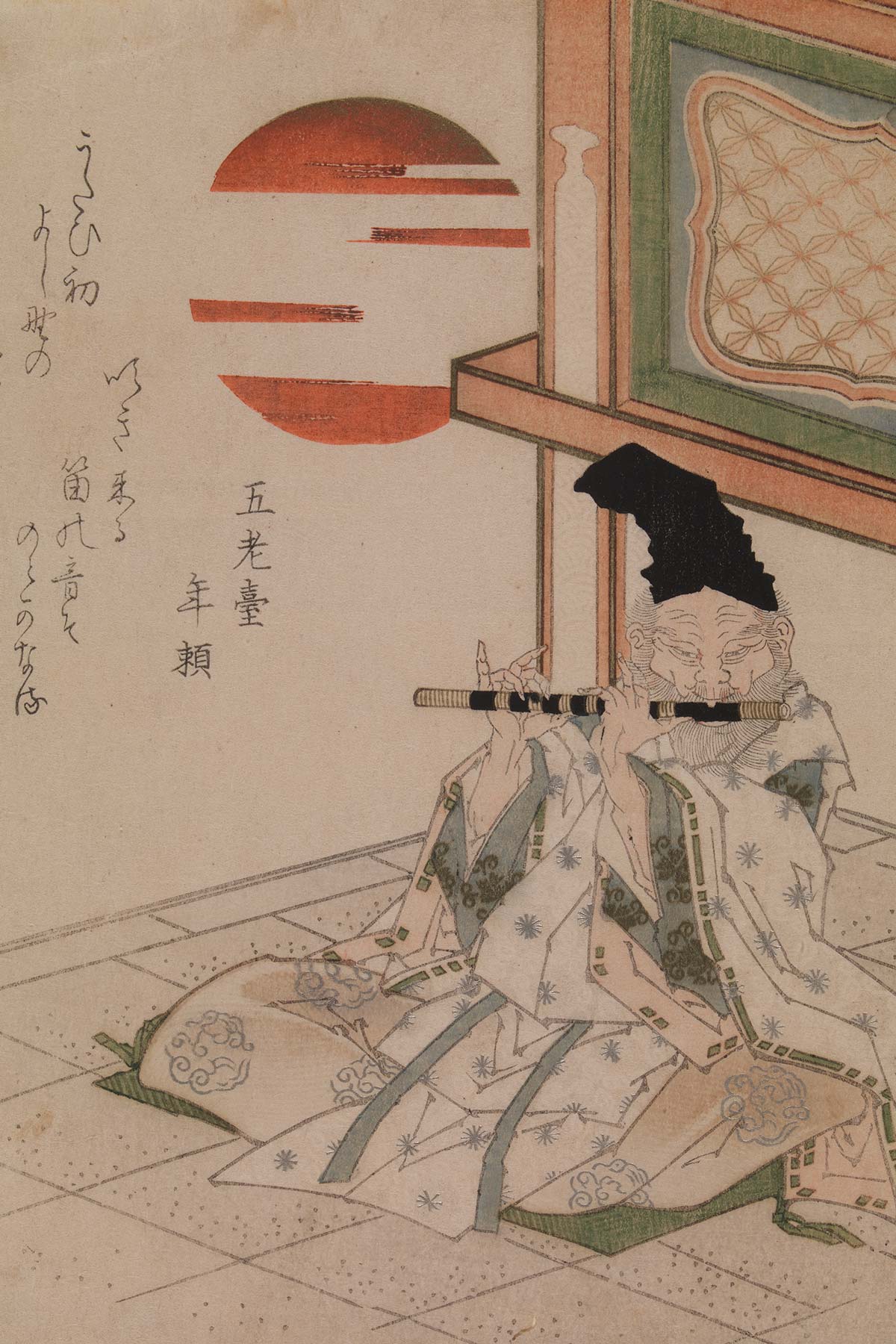

A man of his time, Calouste Gulbenkian was not immune to the fashion for Japonisme and his interest in the art of the Far East is reflected in his art collection, in various Japanese art objects and prints, such as the surimono, exclusive and limited editions of woodcuts, intended for a select public of Japanese society of the time – of which he acquired a representative set, mainly by Totoya Hokkei (1780-1850) – and the ukiyo-e (images of the floating world).

Calouste Gulbenkian’s personal library also reflects his attention and taste for the art and culture of Japan, bringing together various books in French and English. There are a total of 25 titles, published between 1880 and the 1950s, which include some of the reference works of the time on the history of fans, the art of flower arrangements – ikebana -, gardens and prints.

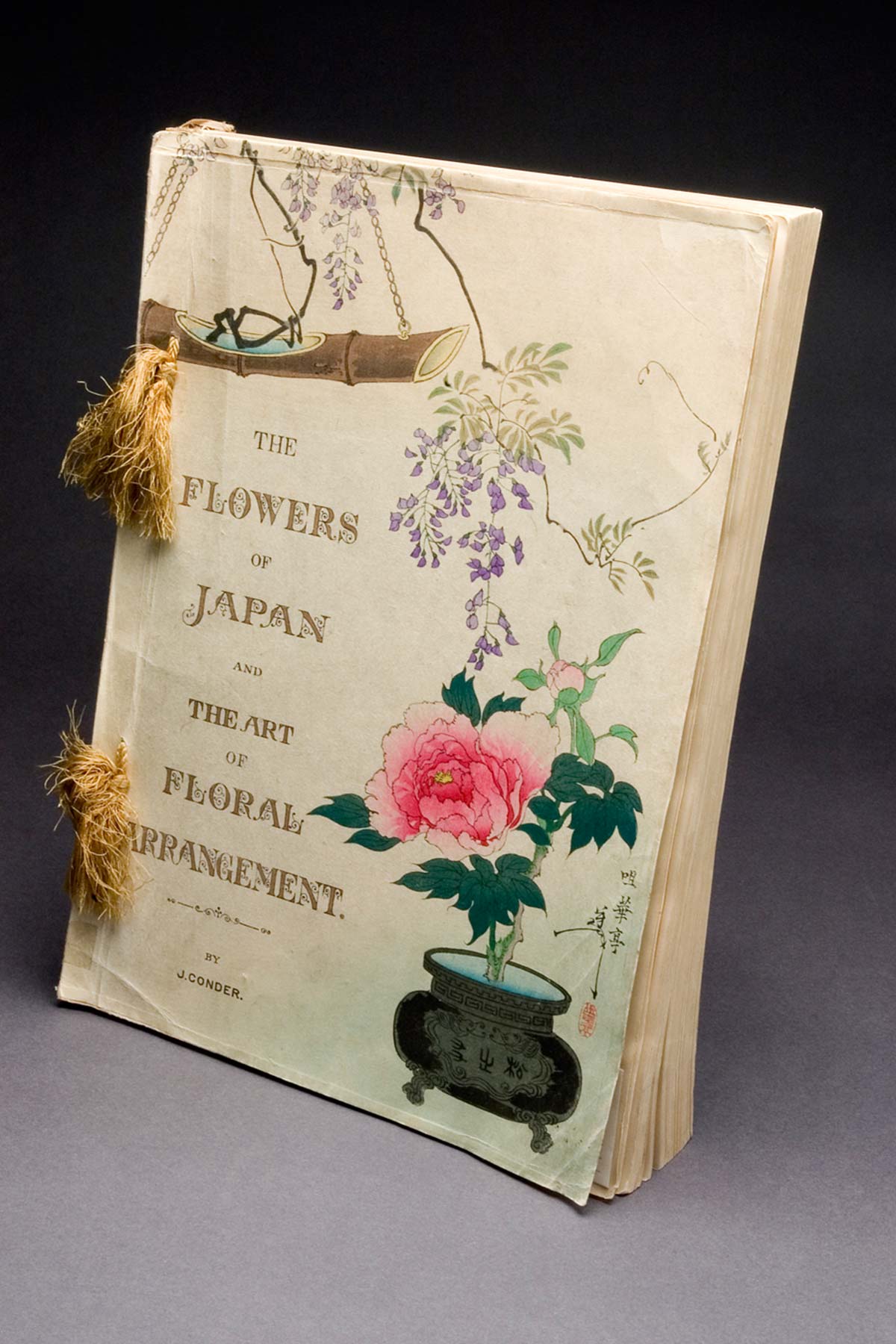

This is the case, for example, of the book The flowers of Japan and the art of floral arrangement, published in Tokyo in 1891. Written by the English architect Josiah Conder (1852-1920) – hired by the Japanese Meiji government as a professor of architecture at the Imperial College of Engineering, he became the architect of the Public Works of Japan – this was the first book to disseminate, in the English language, the Japanese art of floral arrangement, Ikebana. The cover and back cover of this 1st edition were designed by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892) – master of the ukiyo-e painting and woodcut genre -, as well as all the coloured engravings; the illustrations of the interiors were done by the painter Kawanabe Kiosui (1868-1935).

The interest generated by this subject was such that this book had a second, revised edition, with the title The floral art of Japan, published with western style binding and illustrated by Ogata Gekko (1859-1920), Yoshitoshi’s contemporary artist.

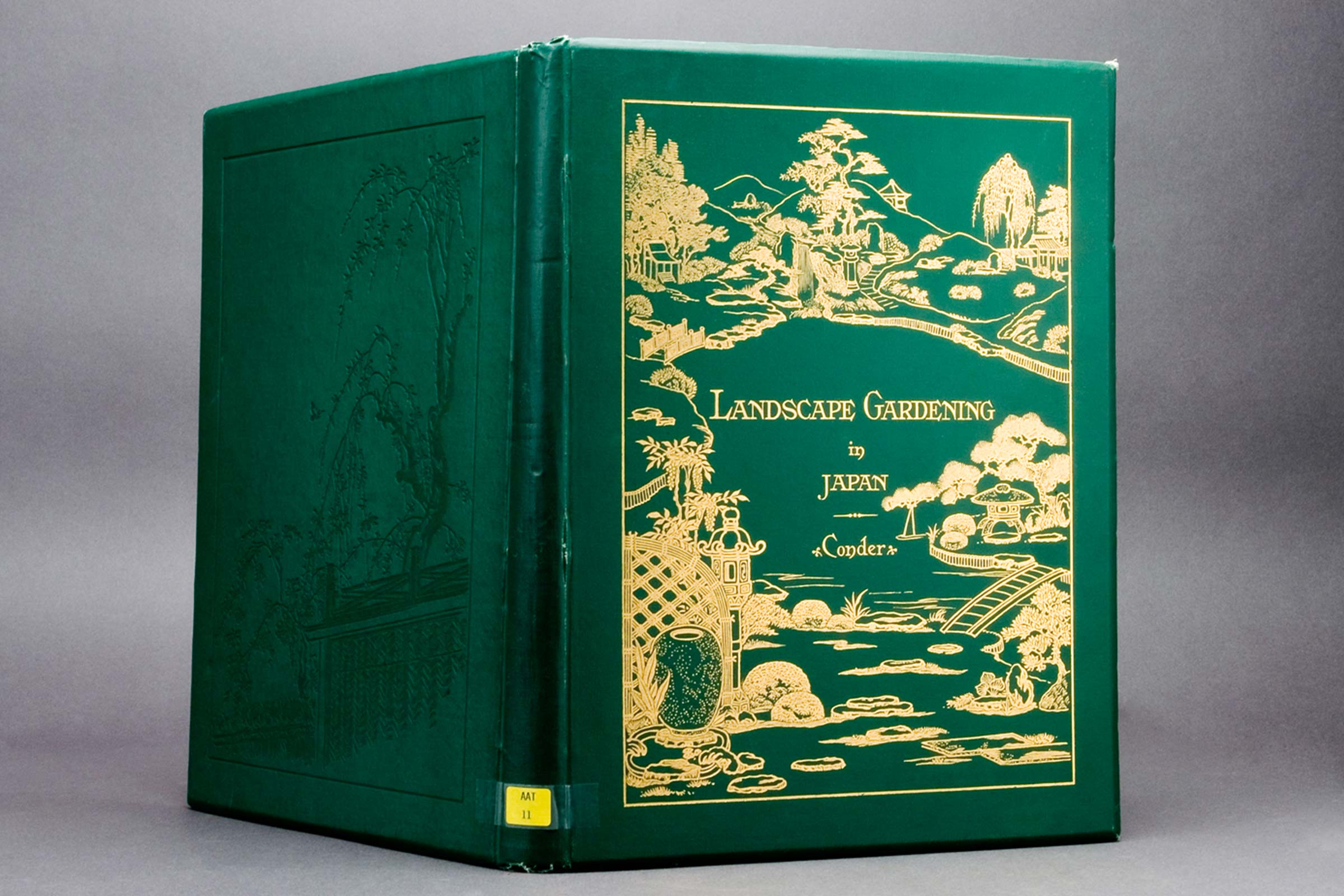

By the same author, Josiah Conder, is the two-volume Landscape gardening in Japan, published in Tokyo in 1893, illustrated with collotypes made by Ogawa Kasumasa (1860-1920), one of the pioneers of photography and photographic printing methods in Japan.

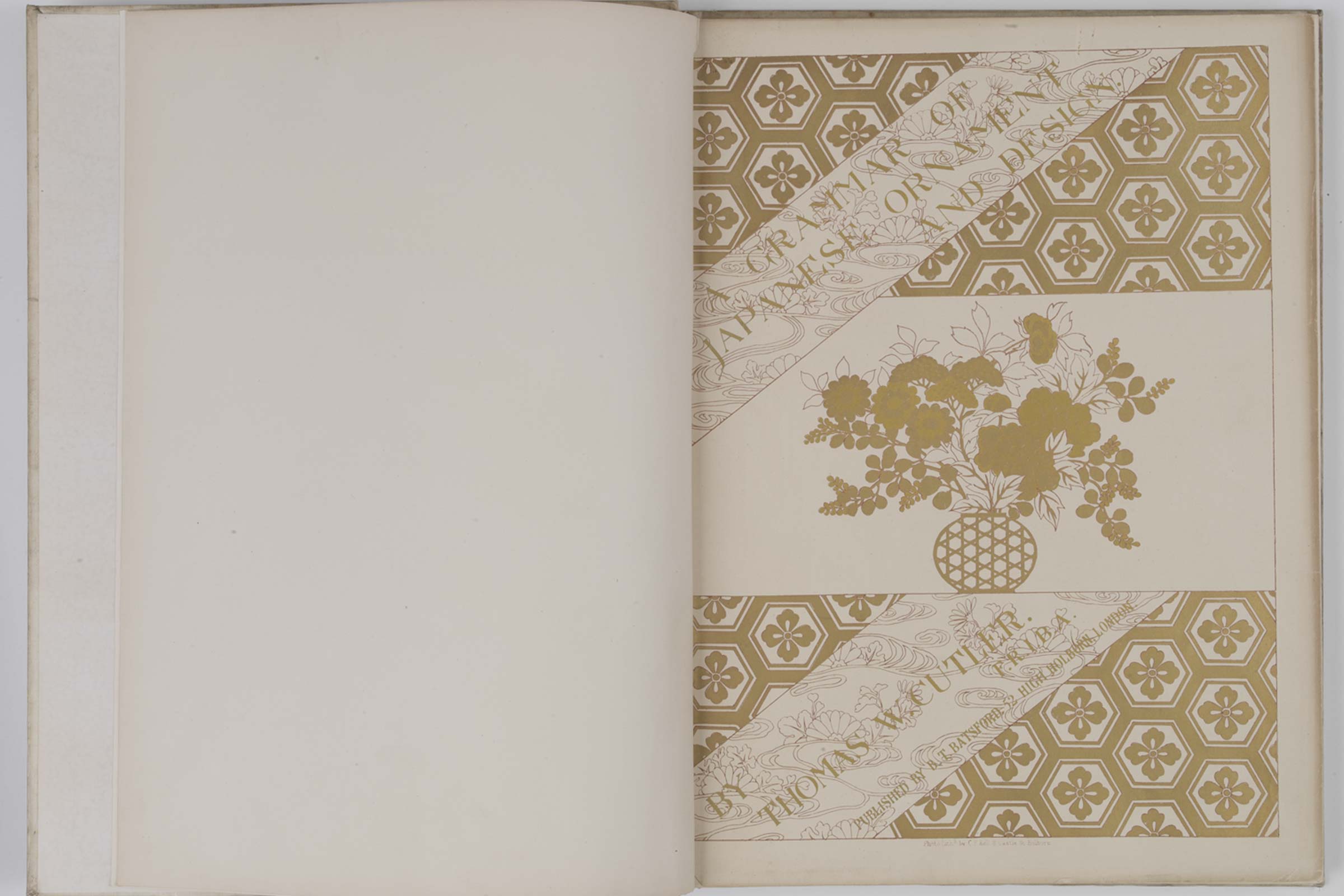

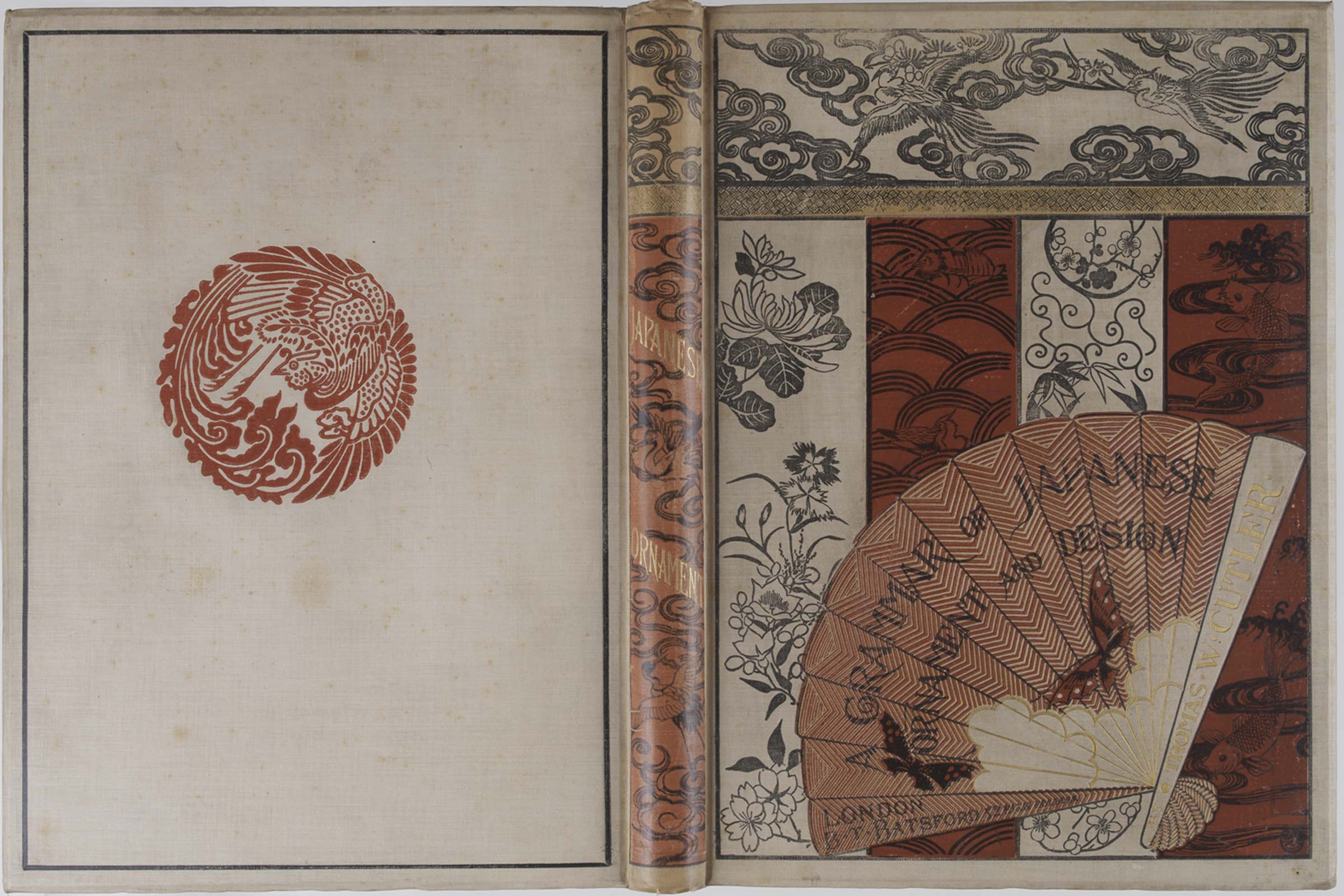

Another of the beautiful books purchased by Calouste Gulbenkian is A grammar of Japanese Ornament and Design, by the English architect Thomas William Cutler (1842-1909), which was, at the time, a kind of manual and guide to the inspiration of Japonisme. Published in London in 1880, this book has a preface illustrated with a black and white woodcut, contains a list and description of the plates followed by pages of text illustrated with seven black and white woodcuts, and 58 full-page lithographic plates, some in colour, some in gold and silver and others in black and white. The cover is original, with drawings of birds, flowers, and fans in gold, red and black.

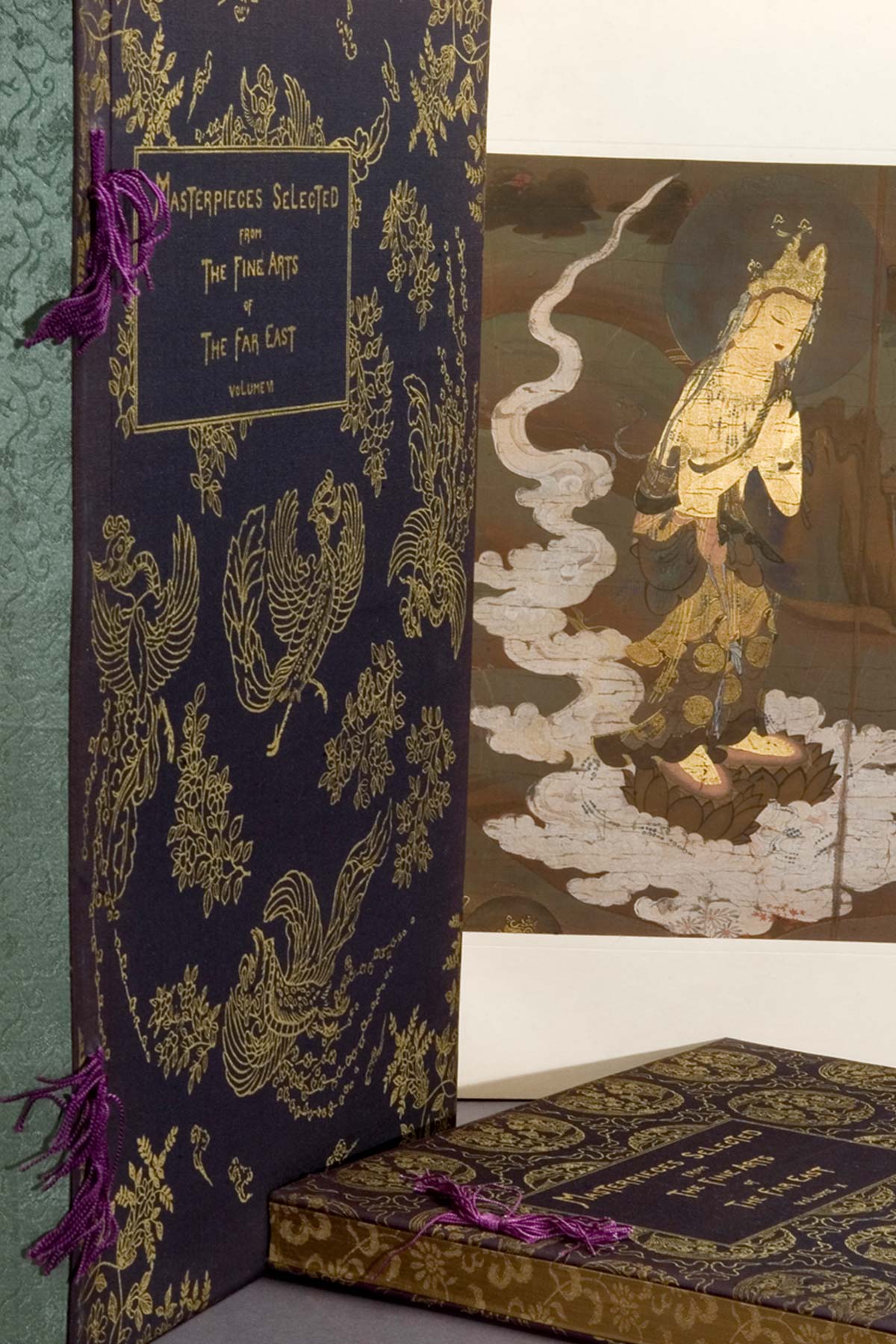

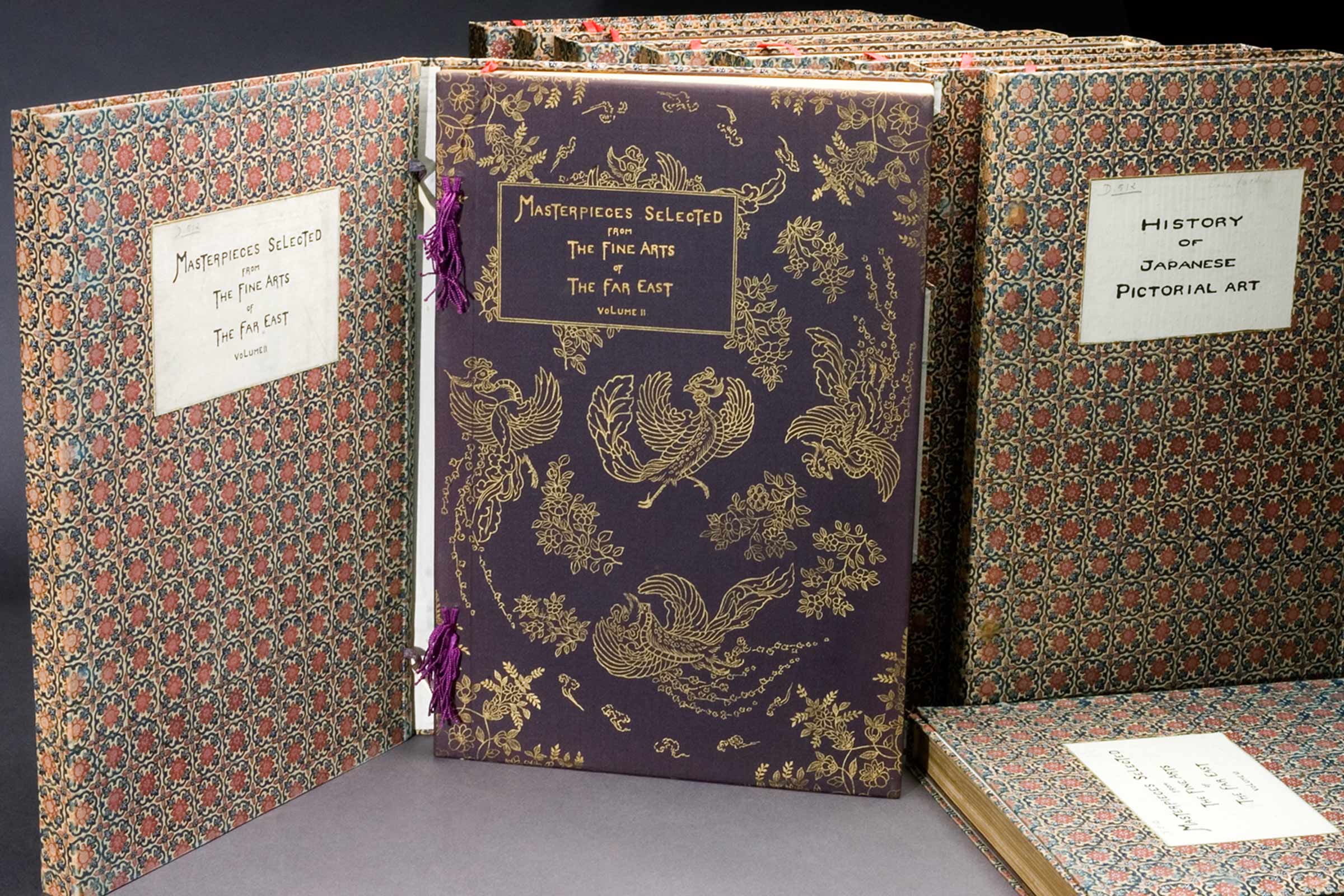

The work Masterpieces selected from the fine arts of the Far East merits a mention here, although the “masterpieces” presented are from both Japanese and Chinese art. Identified in pencil with the reference “D.512” (D for “Documentation”, one of the classifications that Calouste Gulbenkian used to give to the books that he bought and that were part of his private library) and with the information “sans facture” (without invoice), this collection consists of 13 volumes and was published in Tokyo between 1909 and 1910 by the publishing house Shimbi Shoin, whose editions were characterized by the high technical quality of their binding and reproductions.

Each volume is inside a box lined with printed silk, with bone or ivory clasps, the binding is also in printed silk, with purple silk thread. Inside, the texts on each work reproduced are in English – in some volumes also in Japanese – and the numerous reproductions that each volume presents are in black and white – engravings and photogravures on paper – and in colour, being, in the latter case, engraved on silk and coloured by hand. The art of Japan has 8 volumes devoted to it, while Chinese art only occupies 5.

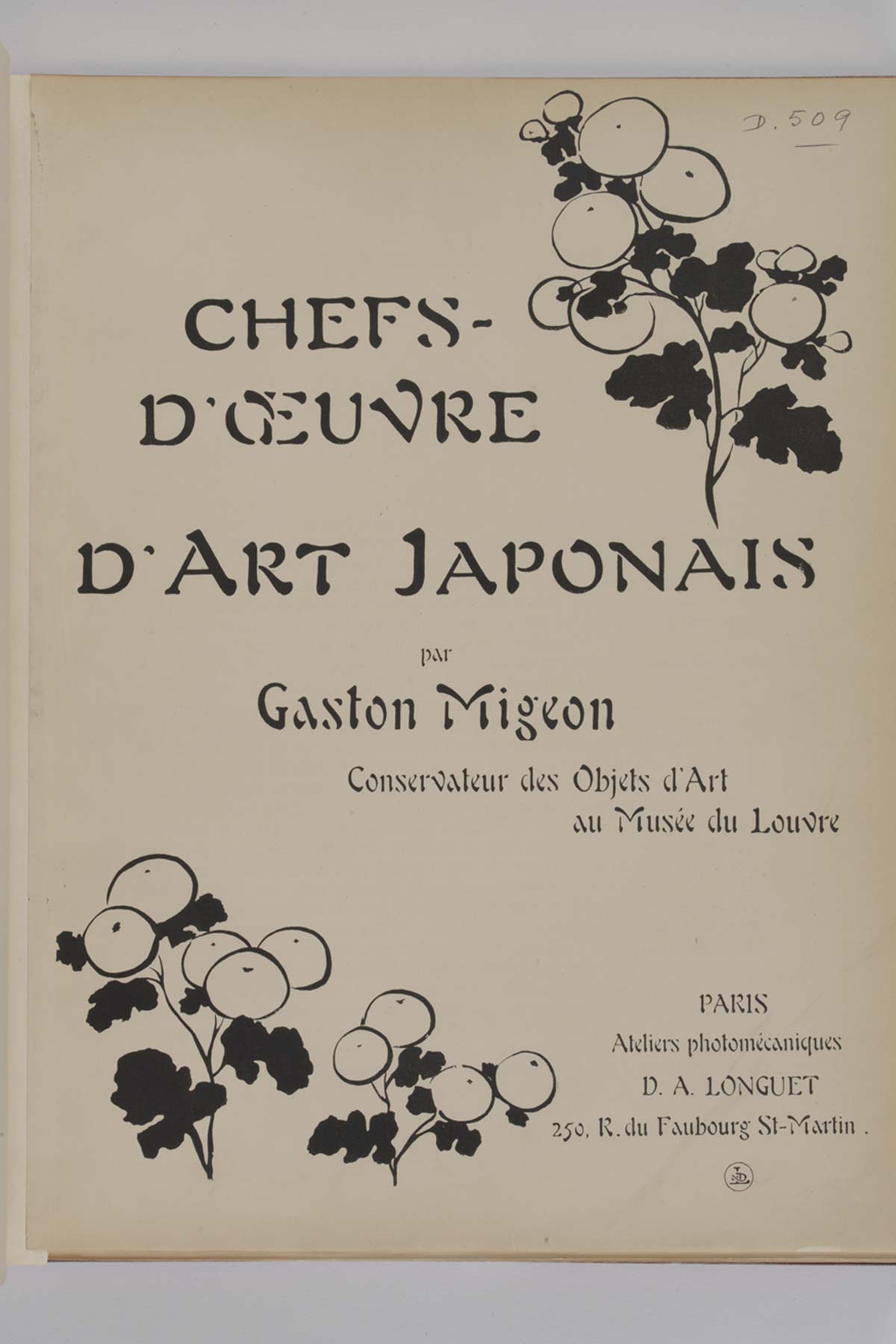

Other books in this set include Au Japon: promenades aux sanctuaires de l’art (1908) and Chefs d’oeuvre d’art japonais (1905), by Gaston Migeon (1861-1930) – who was curator at the Louvre Museum and studied, among other subjects, the history of Japanese and Chinese art -, and auction catalogues from 1911 and 1916, respectively, where Japanese prints were sold.

Works in Calouste Gulbenkian’s personal library

A grammar of Japanese ornament and design […] / Thomas W. Cutler, 1880

Artistic Japan / compiled by S. Bing, 1888

The kokka / The Kokka Publishing Company, [1889]

The flowers of Japan and the art of floral arrangement / Josiah Conder, 1891

The flowers of Japan and the art of floral arrangement / Josiah Conder, 1892

Landscape gardening in Japan / Josiah Conder, 1893

Fans of Japan / Charlotte M. Salwey, 1894

The floral art of Japan / Josiah Conder, 1899

Chefs d’oeuvre d’art japonais / Gaston Migeon, [1905]

Choice of Korin and Kenzan, [1906]

Masterpieces of thirty great painters of Japan, [1906]

Au Japon / Gaston Migeon, 1908

Chats on oriental art / J. F. Blacker, 1908

Painting in the far east / Laurence Binyon, 1908

Masterpieces selected from the fine arts of the Far East, 1909

Étoffes japonaises / M. P.-Verneuil, [1910]

Catalogue of a collection of Japanese colour prints…, 1911

Les estampes japonaises / W. de Seidlitz, 1911

Japanese colour prints / Edward F. Strange, 1913

Japanese temples and their treasures, 1915

Catalogue of an interesting & varied collection of Japonese colour prints […], 1916

Faïences, manuscrits et miniatures, robes de la Perse, livres japonais […], 1930

Portraits d’acteurs japonais du XVII au XIX siècle / Galerie Huguette Berès, [195-]

Works from the Library

A selection of books and magazines, photographs, exhibition catalogues and other documents whose themes relate to the history of art, modern and contemporary visual arts, Portuguese architecture, photography and design.