Around the House(s)

At a time when lockdown has once again become reality, with communal places now restricted and people confined to a new ‘normal’ mobility, everyday life is lived in a predominantly virtual world. Quickfire images and troubling information seem to leave no room for contemplation, reflection or just being. But houses still stand out as places of intimacy, shelter and safety, spaces where memories are made, where now, more than ever, we share our personal life and professional reality, in an ambivalent register, burgeoning with ideas, a stage for re-reorganisations.

Artworks are filled with an avatar spirit, in which the encounter with home interiors might or might not be profitable. Human absence can make itself felt, or presence can be absence, as reflected in Filipa César’s diptych, Product Displacement (2002).

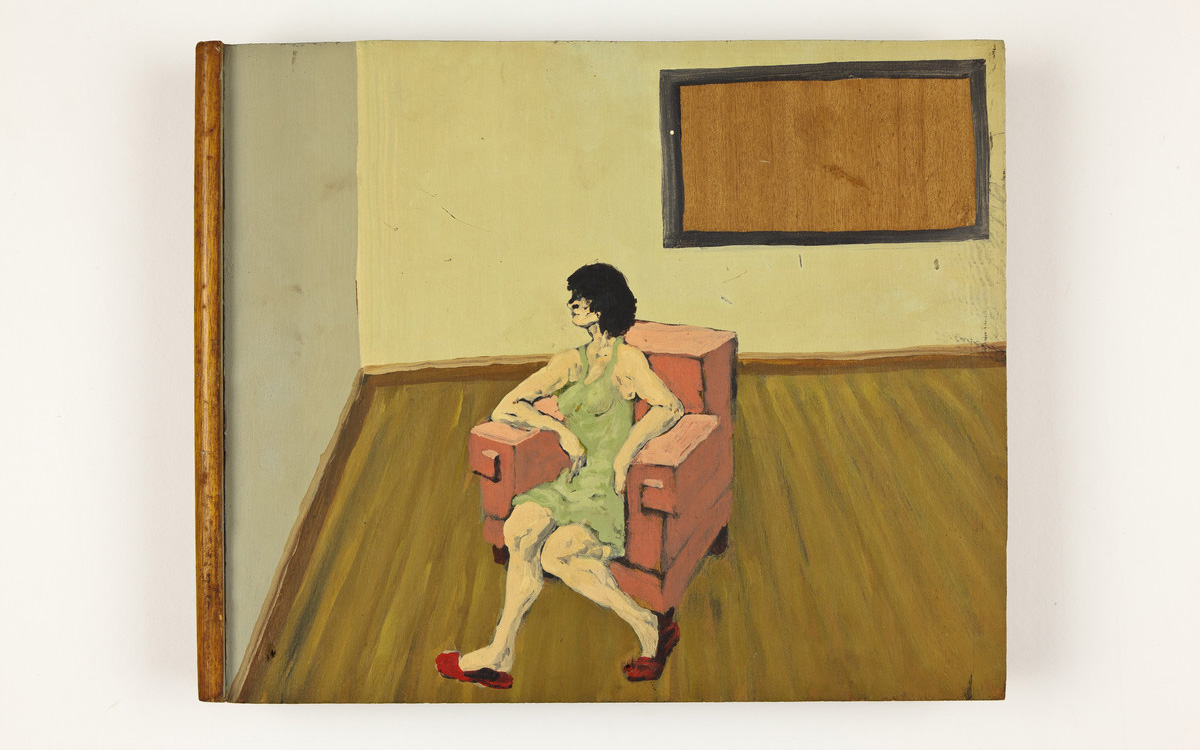

In this video, people move through the house but they don’t communicate with each other, as if they merely fulfil the function of the objects around them. This human absence-presence is equally visible in Jorge Varanda’s isolated spaces, where the characters identify themselves in the raw, empty environment, in the very architectural matter of the pictorial space.

The idea of apparent human absence can also be seen in the series of photographs Vita Brevis, by Maria Beatriz. Although the pumpkin and dishcloth sitting on the table allow us to guess at the movement of someone occupying that place, the photograph leaves an empty space, cleansed of poetry and curiosity.

Emmerico Nunes’ intimacy is reflected in an amusing night-time scene whose characters fail to connect: the woman lying in the bed and the man sleeping on the floor, leaning against the bed, nonetheless convey some serenity.

As for Pierre Nora’s ‘places of memory’,1 sites of remembrance, where collective and individual memory crystallises, there is a general and personal identification. For Pierre Nora, memory and history reveal a confrontation between the two. Memory, with its origin in spaces, gestures, images and objects, is absolute; instead, history is the relationship between things in a temporal continuity, involving relativity. The idea of memory can become bound precisely because it is a space of identity, of places that are obligatory and necessary.

In the same vein as these places of memory, we find Penélope, a work made in 2000 by Ana Vidigal, formed of a mattress covered with letters, correspondence between the artist’s parents during the war. They are memories of life perpetuated in a personal space, a place of love and intimacy.

In Tiempo Sosegado [Peaceful Time], from 1985, the Spanish artist Esperanza Huertas shows a large number of domestic objects scattered around the room, including antiques, flowers, books, games, a playful presence in disquieting colours, a necessary place.

Functioning as a scenographic installation, Untitled (2007/8) by Heimo Zobernig is a large installation with long RGB curtains (red, green and blue – used as backgrounds for filming), which cut the space and create new spatial framing, where the curtains become the walls of the house on which paintings can be hung or against which shelves empty of books can be leant. Heimo Zobernig proposes the construction of a house, challenging but at the same time protective, with a specific functional identity.

- Pierre Nora, «Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire», in Representations, No. 26, Special Issue: Memory and Counter-Memory, Spring 1989, pp. 7-24.