Ancient Egypt in European Illuminated Manuscripts

From Exodus to Flight

As the setting for various Bible stories, Ancient Egypt and some of its characterising features, such as the figure of the Pharaoh, the river Nile or the desert, were often evoked and illustrated in European illuminated manuscripts dedicated to Christian devotion and worship.

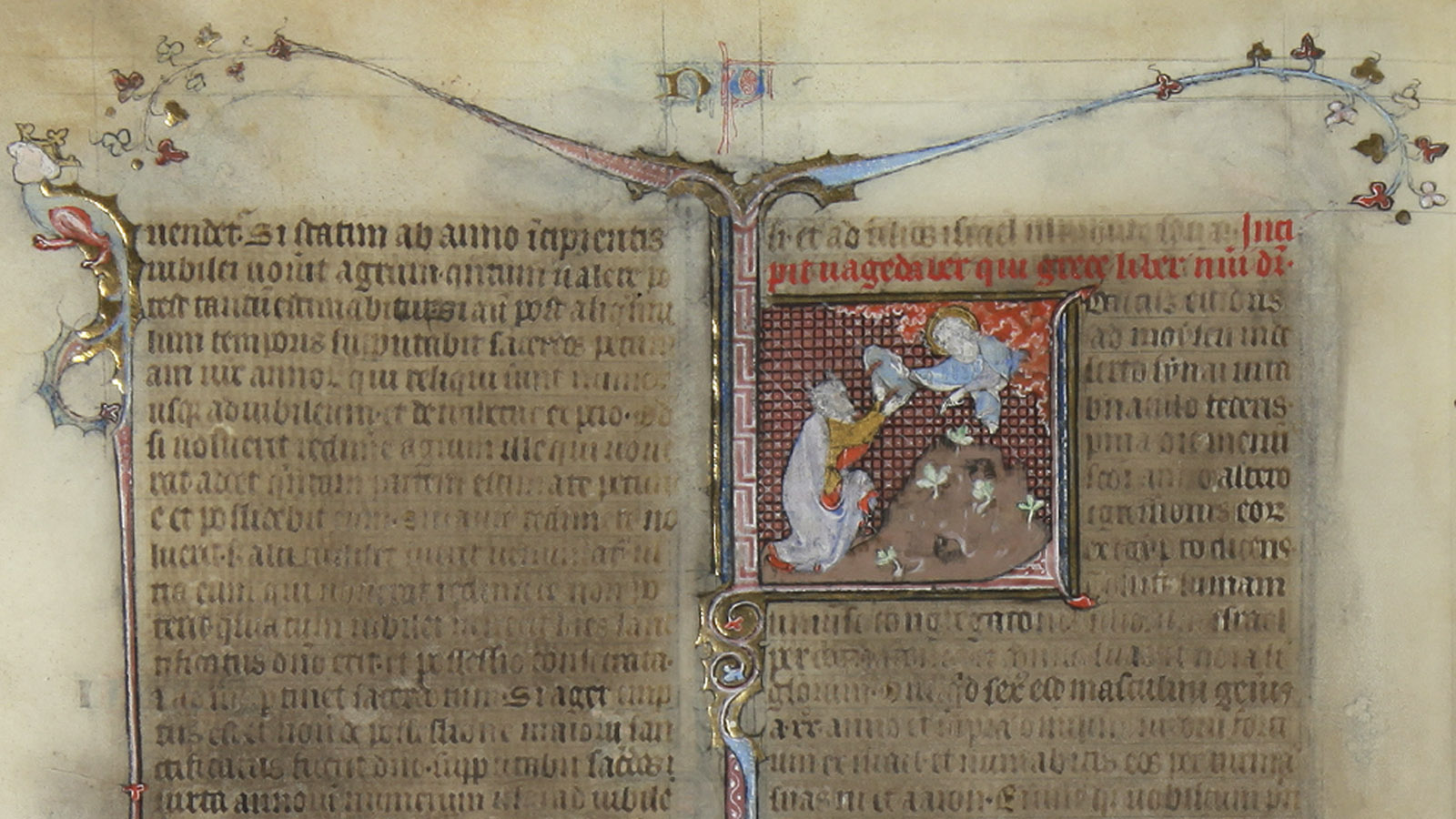

In the case of the Old Testament, in particular the book of Exodus, a frequently-approached episode is the life of Moses, who was chosen by God to free the tribes of Israel, enslaved by the Pharaohs. In fact, according to the biblical narrative, Moses, sentenced to death for having been born a Hebrew, was left as a baby by his mother in an ‘ark of bulrushes […] with asphalt and pitch […] in the reeds by the river’s bank.’ (Ex 2:3), where he was found by the Pharaoh’s daughter, who ended up adopting him and calling him ‘Moses, saying: ‘Because I drew him out of the water.’ (Ex 2:10).

According to the theological treatise Speculum Humanae Salvationis, dating from the early-14th century, and, more specifically, to a midrash or biblical commentary, Moses is believed to have come across the Pharaoh as a child, playing with his crown, throwing it to the floor and standing on it, an incident viewed as a bad omen by the Egyptian authorities. As an adult, Moses met the Pharaoh in the hope of persuading him to free the Hebrews, or else risk Egypt being punished by God with ten plagues, which is indeed what happened according to the Old Testament.

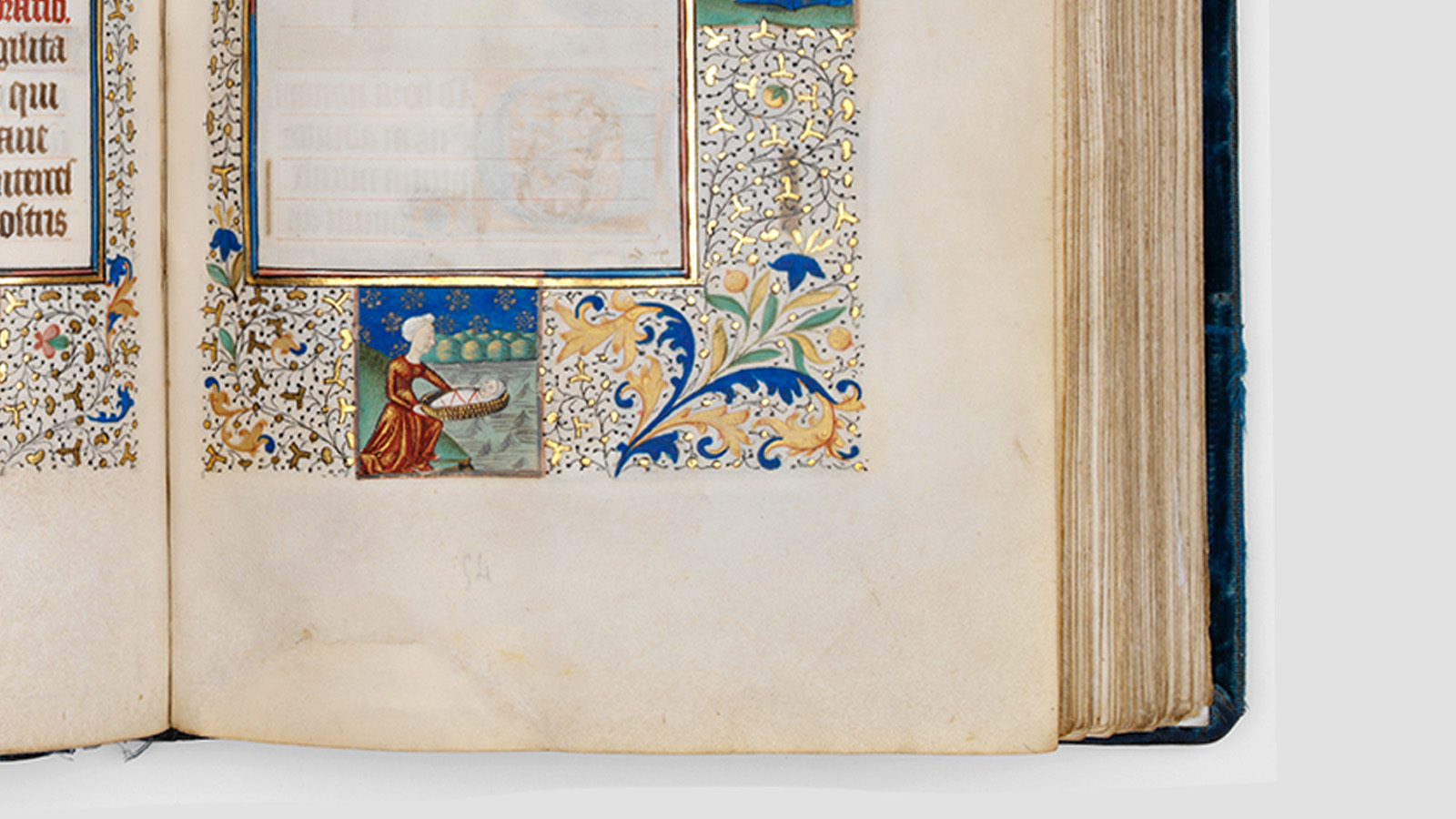

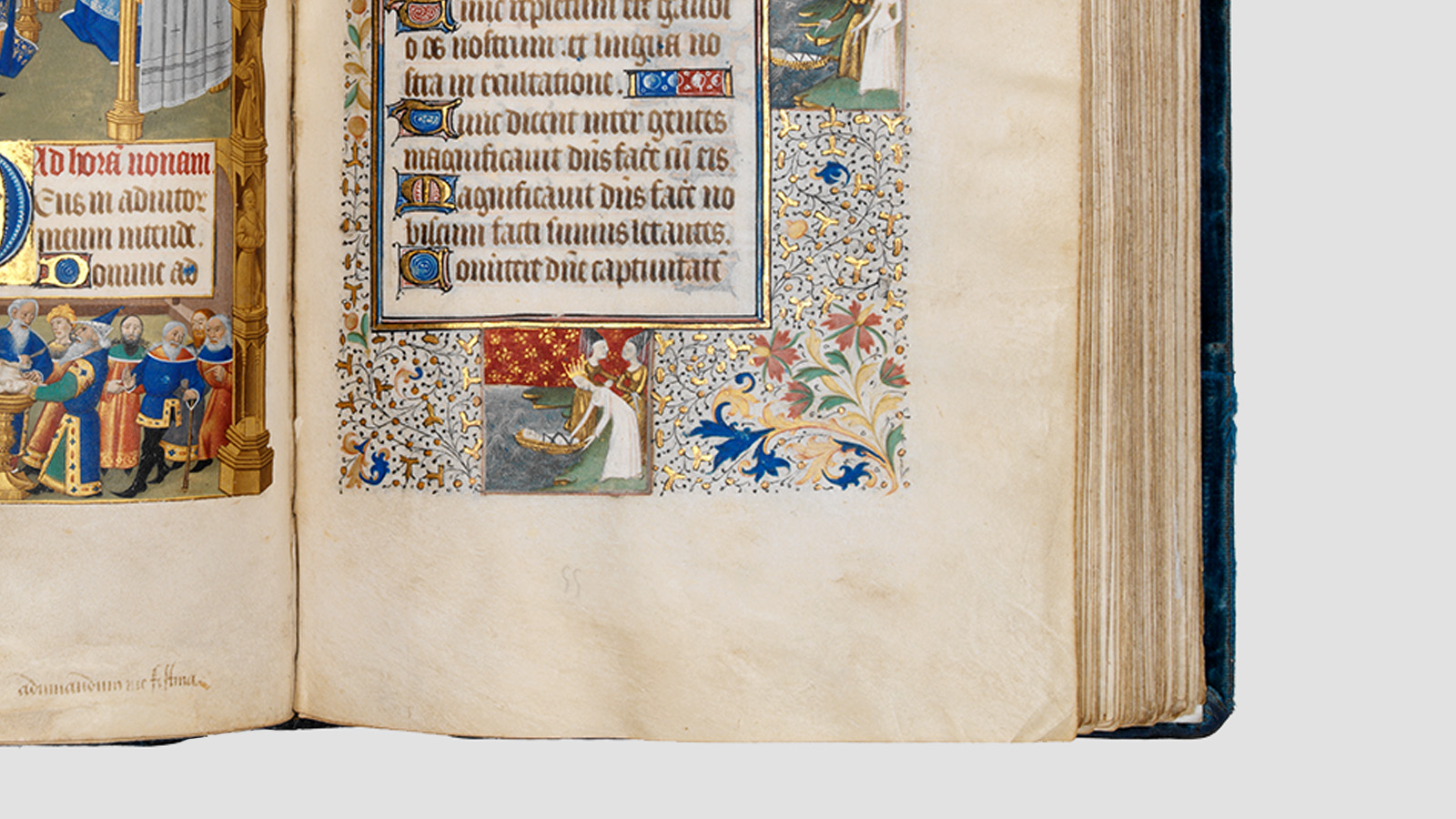

Through their connection to Moses’ life, the River Nile, the Egyptian princess and also the Pharaoh thus function as elements that, through the Bible, its commentaries and interpretations, and illuminated manuscripts, formed the medieval Christian imagery of Ancient Egypt. In the Gulbenkian Collection, a book of hours produced in France between 1460 and 1470 includes various illuminations that illustrate these moments, with the representation of a baby being left and then taken from a river, as well as the Egyptian princess and the Pharaoh, dressed and crowned in the European fashion of the period when the book was created.

The book of Exodus continues after these episodes, highlighting the role of Moses as the leader in freeing the Hebrews from the Pharaohs’ control, a process that involved a long journey through Egyptian territory to the so-called Promised Land, including the famous crossing of the Red Sea and the mountainous desert peninsula of Sinai. It was during this journey that some of the foundational moments of Judaism and Christianity occurred.

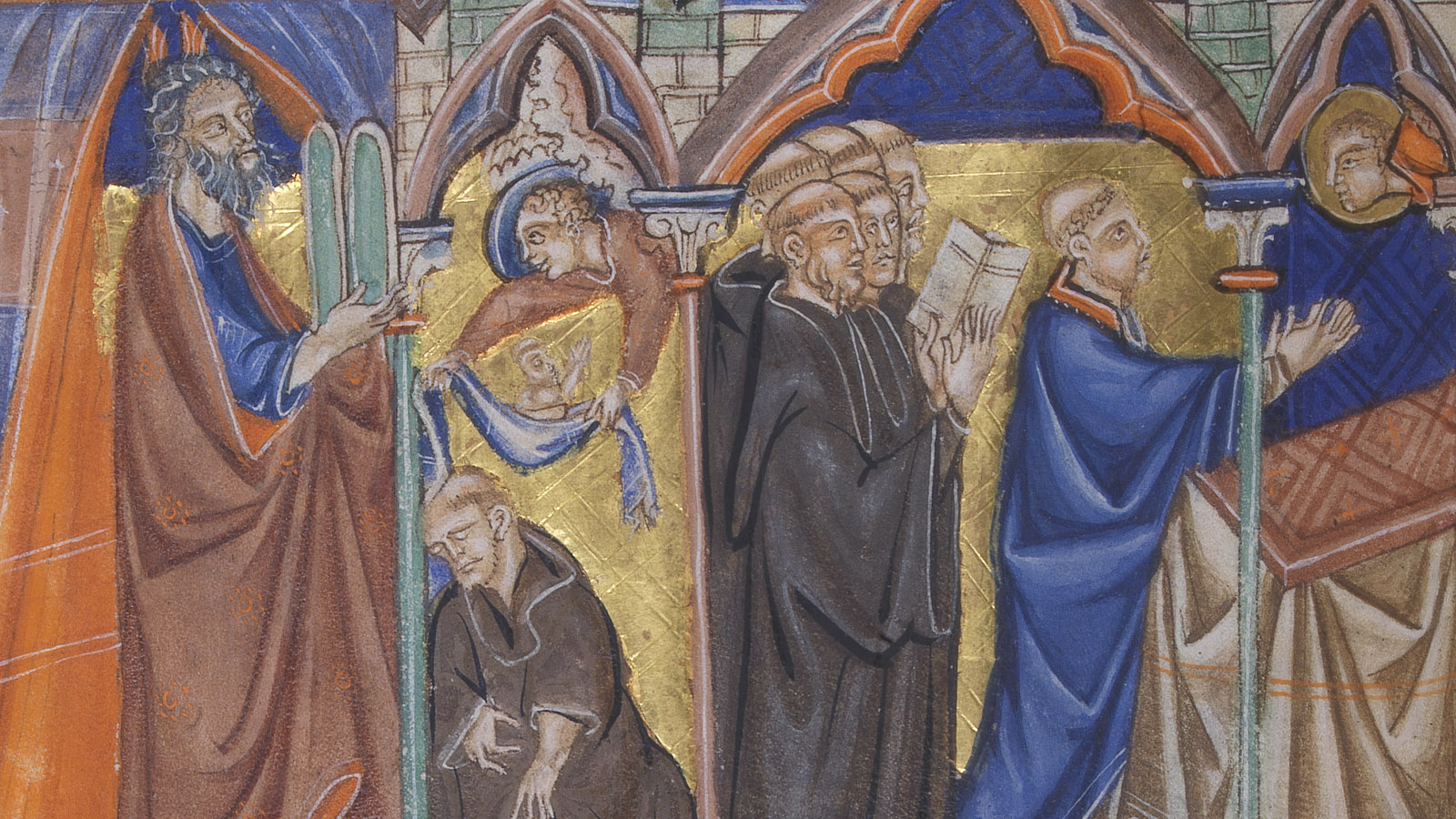

On Mount Sinai, God gave Moses the stone tablets bearing the Ten Commandments, an episode represented in a miniature in a Holy Bible in the Gulbenkian Collection, dating from c. 1310-1320. These tablets are kept in the Ark of the Covenant which, in turn, is protected in the Tabernacle, a sanctuary composed of ‘ten curtains woven of fine linen, and of blue, purple and scarlet thread’ (Ex 36:8), which is illustrated in the Apocalypse belonging to the Gulbenkian Collection.

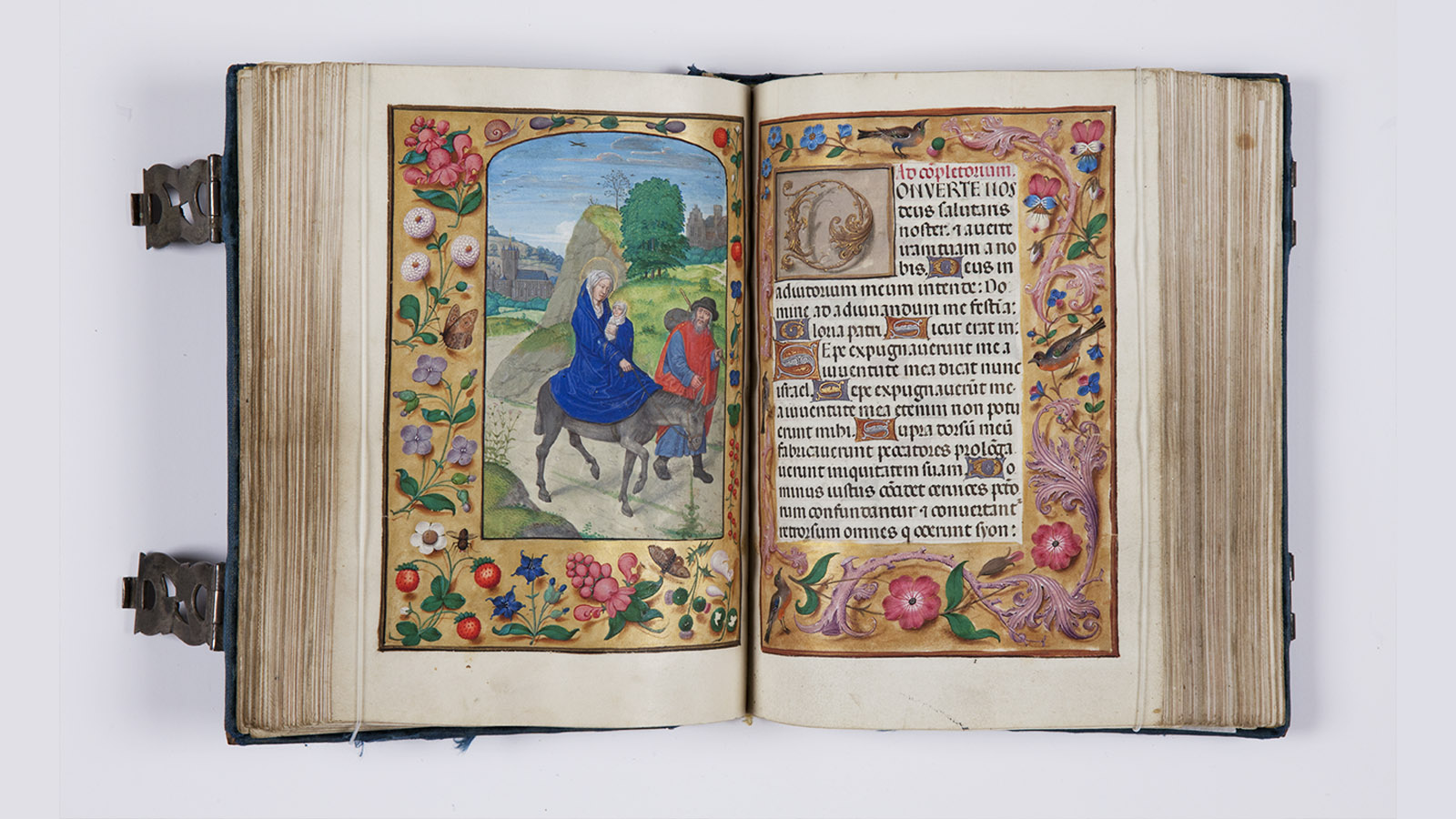

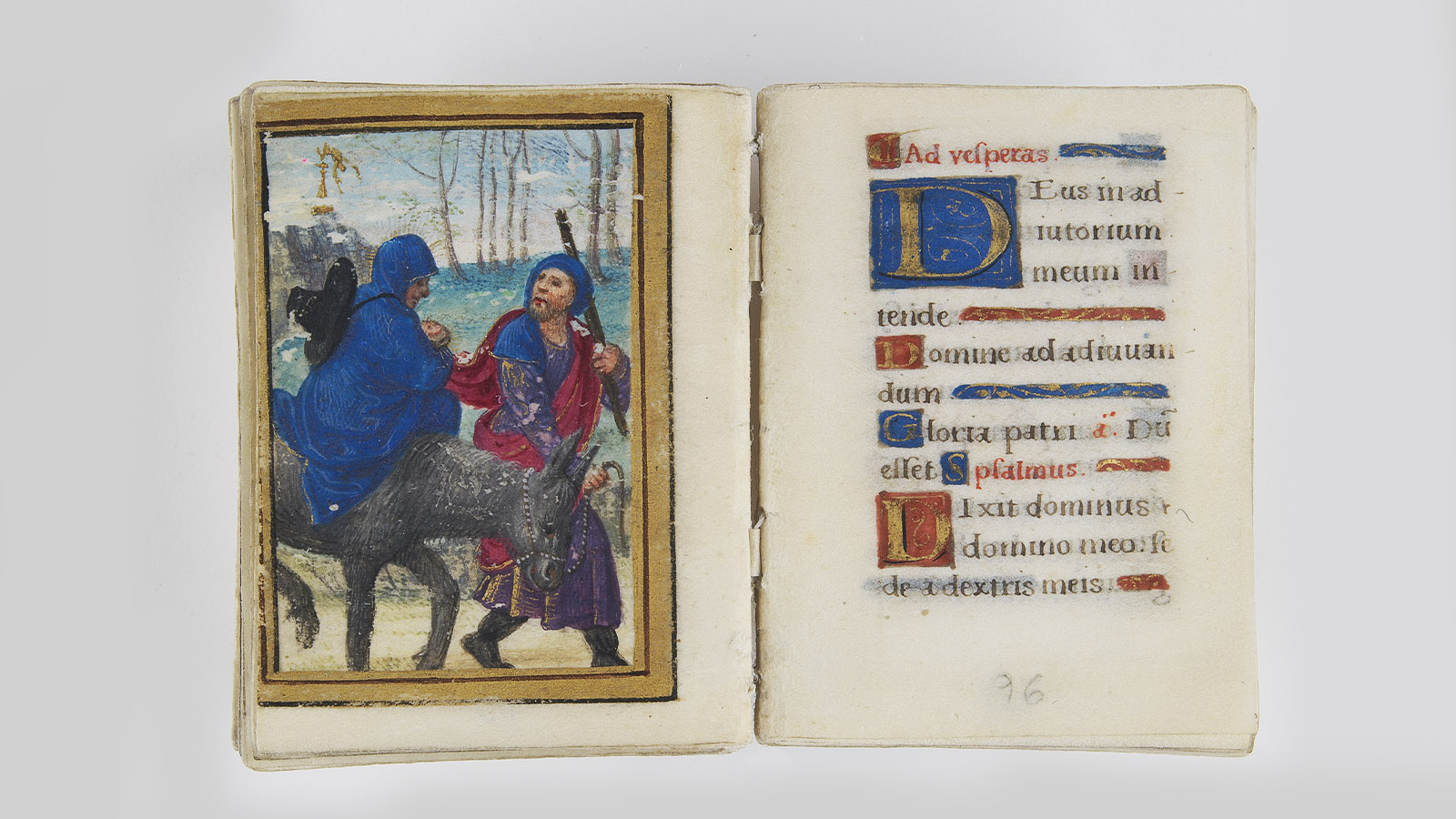

Another journey in the same territory, but in the opposite direction, is mentioned in the New Testament. According to the Gospel of Saint Matthew (Mt 2:13-15), Joseph fled Bethlehem by night to take the Virgin and Child to Egypt, on the advice of an angel who appeared to him in a dream and revealed Herod’s plans to kill Jesus. But, given that it is mentioned so briefly in the Bible, how do representations of this episode situate the action in Ancient Egypt? The illuminated manuscripts in the Gulbenkian Collection offer us some examples.

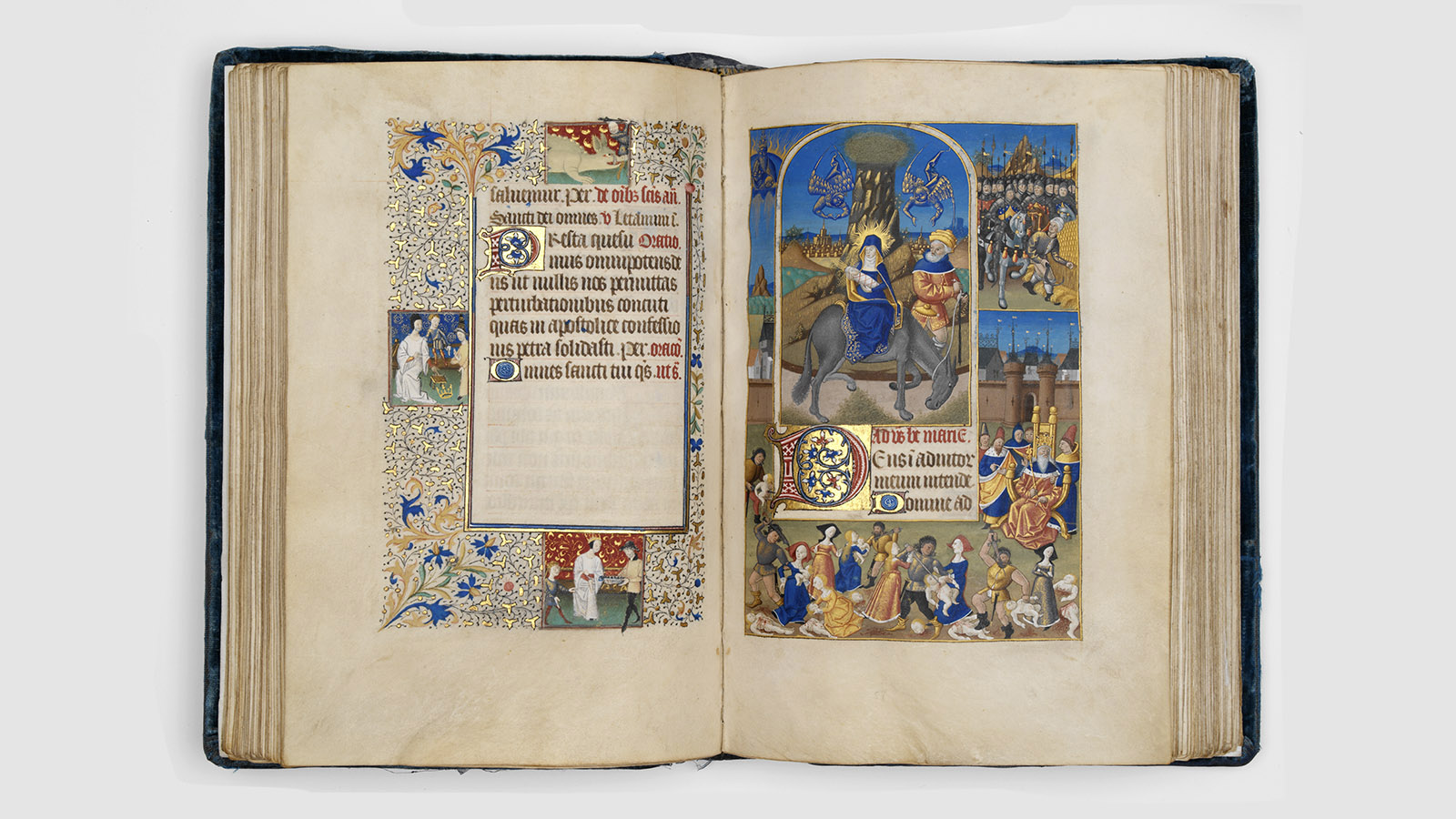

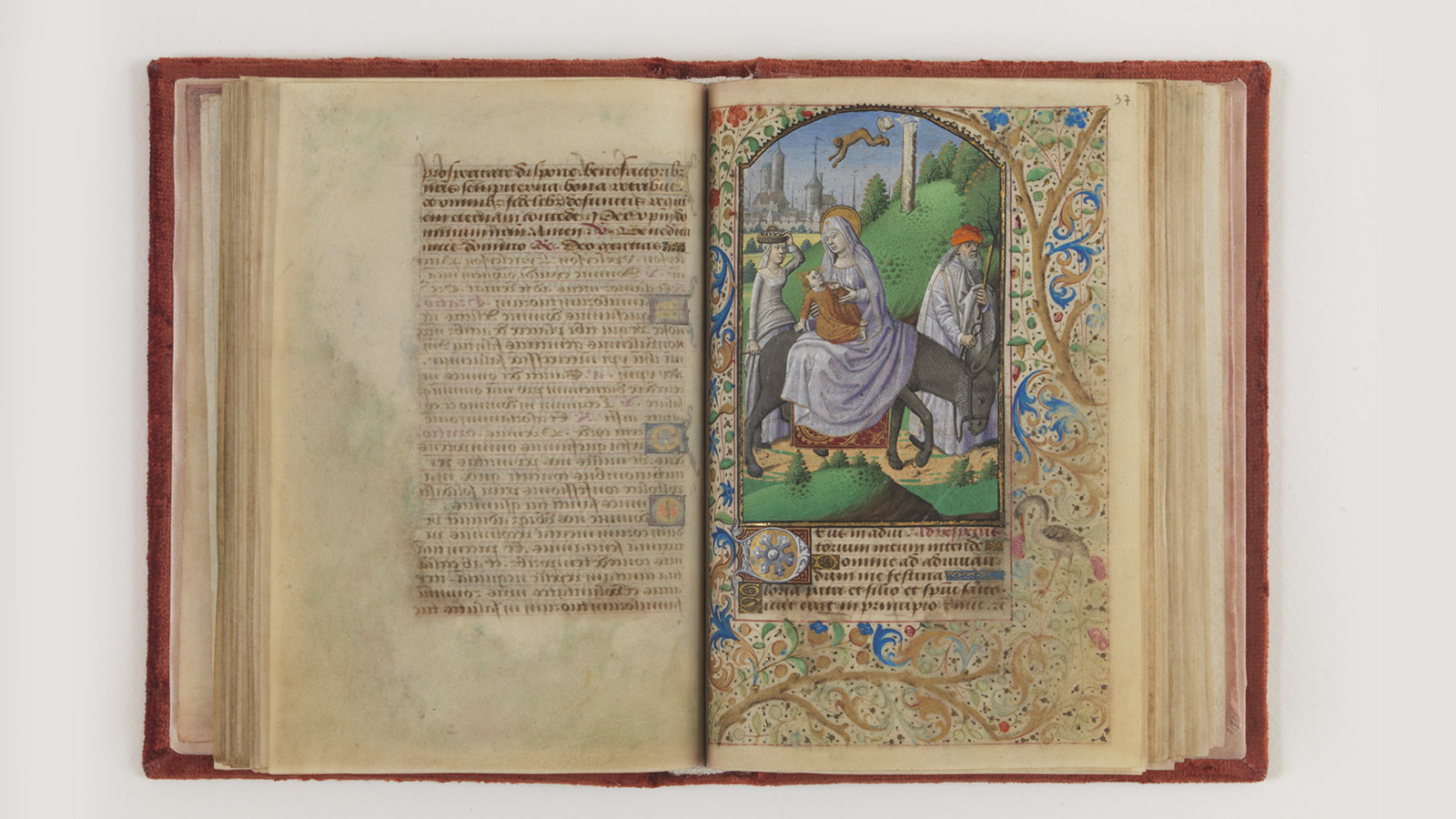

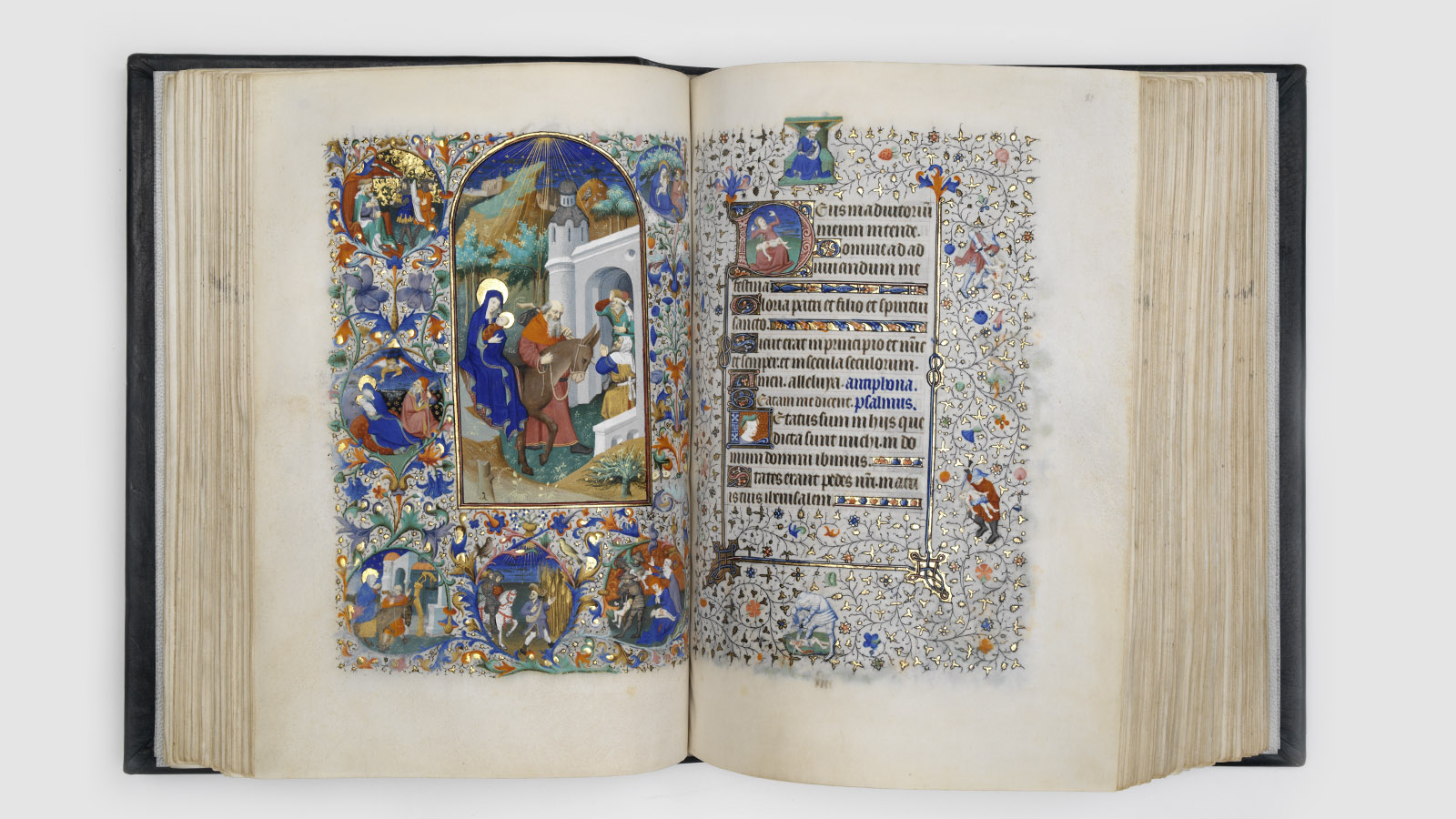

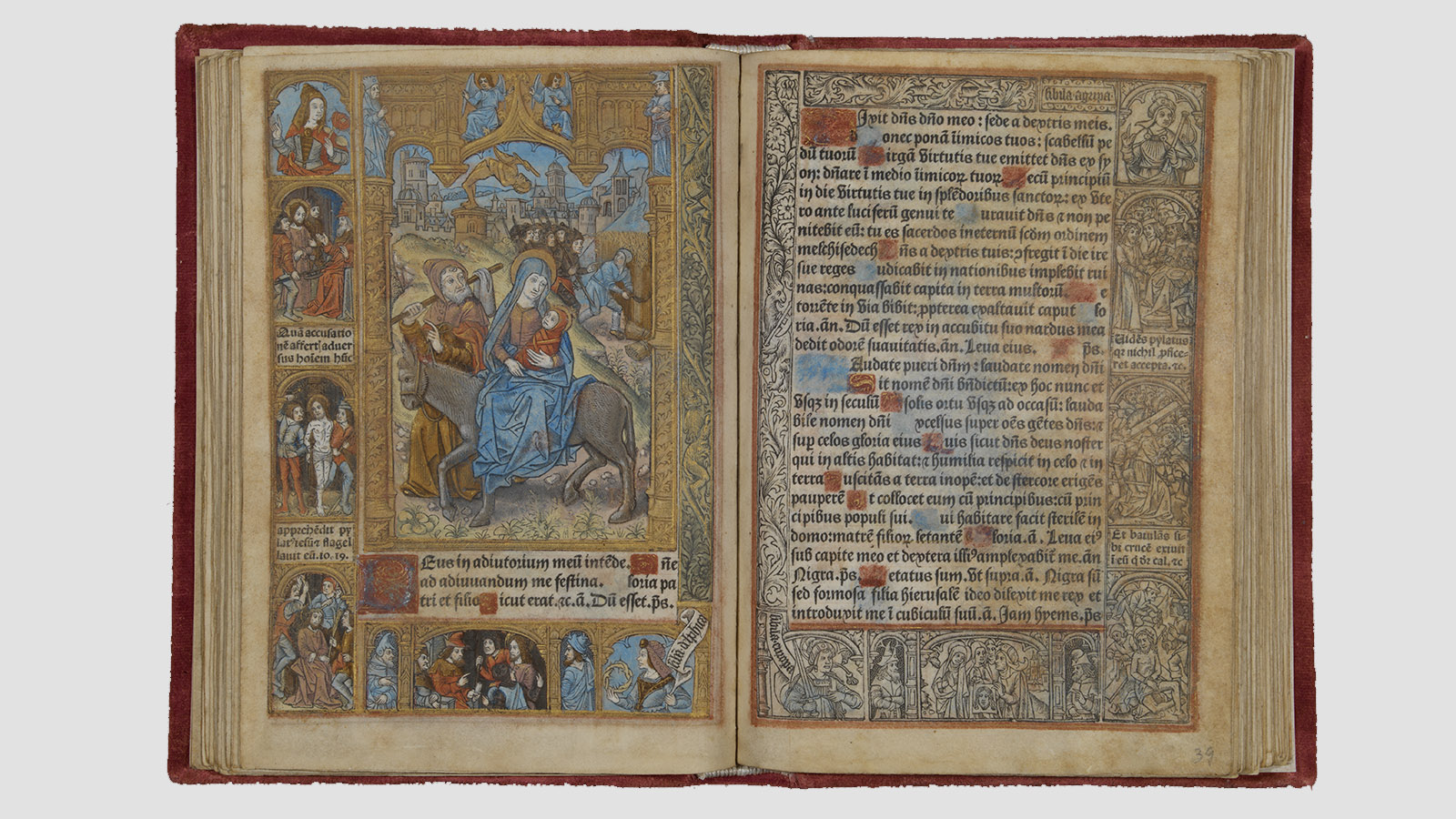

In the Franciscan Breviary, Joseph’s journey, leading the Virgin on a donkey with the Infant Jesus in her arms—the predominant iconographic scheme of this theme from the Middle Ages to the 15th century—is framed by a palm tree, which suggests they are travelling through the desert. Similarly, in the Apocalypse belonging to the Gulbenkian Collection, a tree resembling a palm separates two different episodes, reinforcing their temporal simultaneity in different spaces: the scene of the massacre of the innocents, inflicted on all male children under the age of two in Bethlehem and its environs at the order of King Herod (when he realises that Jesus has fled); and the moment of that flight through the desert.

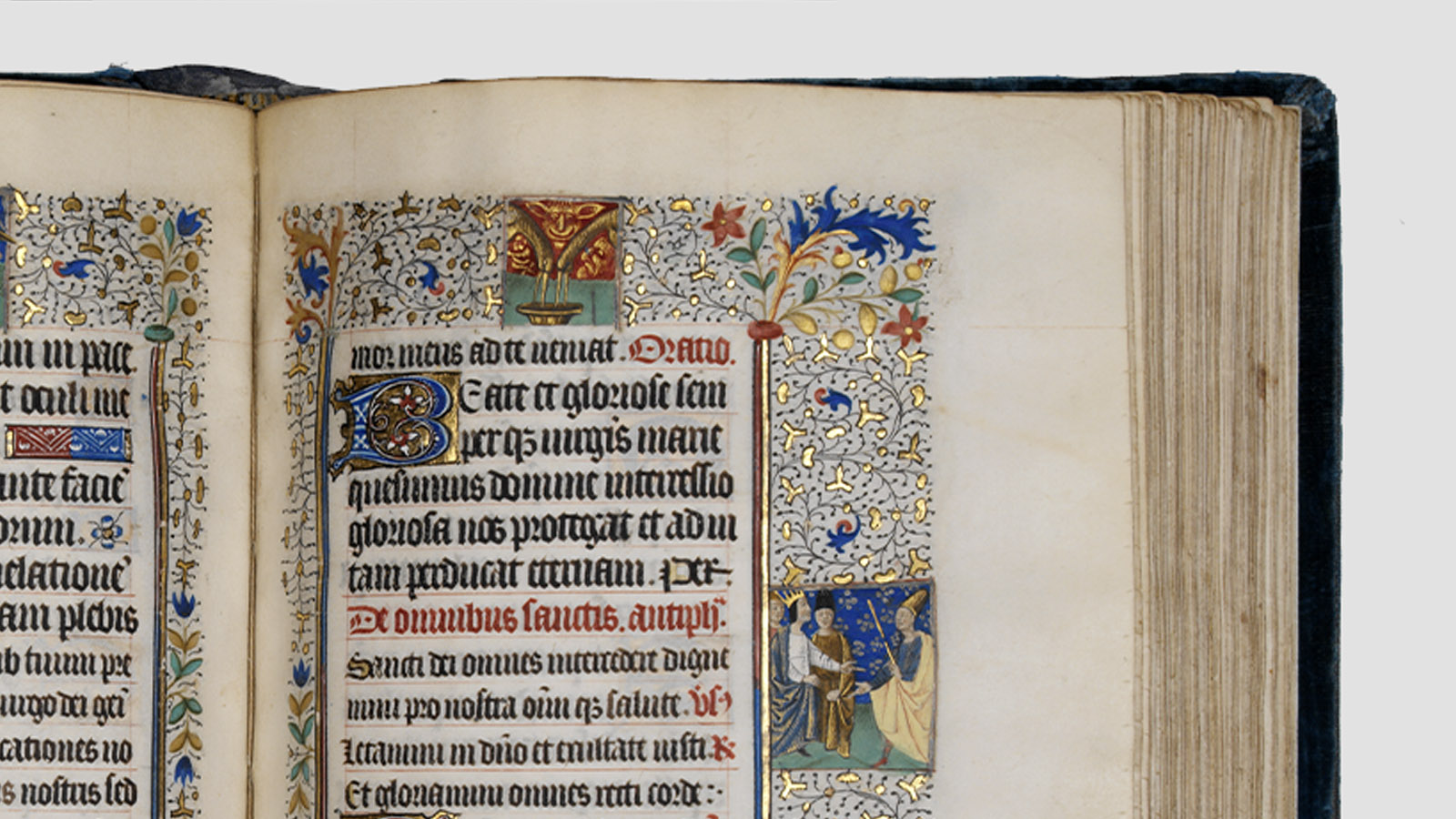

Other works in the collection, books of hours intended for private devotion, mostly for members of the nobility rather than clerics, feature elements that, although not based on an archaeological knowledge of Egypt, enhance this geographic evocation even if they stem from popular sources, not regarded as official by the medieval Christian church, but tolerated by it. In some miniatures we see in the background an urban landscape that, despite the walled configuration or architecture typical of medieval Europe, could represent Sotinen, mentioned in the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew as the Egyptian city that welcomed the Holy Family, in the region of Hermopolis.

Some illuminations also depict columns with statues, with a classical or demoniacal appearance, in a state of collapse or dereliction, representing the miracle of the shattered idols before the Holy Family passed by. Included in the same apocryphal gospel, this miracle reinforces the medieval Christian image of Ancient Egypt as a pagan place where several gods were worshipped. Employing this episode in a book of this type also allows for the justification of the prophecies of the Old Testament (Is. 19:1 – ‘the Lord rides on a swift cloud, and will come into Egypt; The idols of Egypt will totter at His presence’ and Jer. 43:13 – ‘He shall also break the sacred pillars of Beth Shemesh that are in the land of Egypt; and the houses of the gods of the Egyptians he shall burn with fire’), a very common situation in a period when the image served to stimulate theological commentary among the faithful, who were concerned with typologically associating the Old Testament with the New.

Boccaccio’s Isis

While the image of Ancient Egypt in medieval Europe was spread through illuminated manuscripts linked to religion, profane literature also contributed to conveying an idea of Egypt, particularly during the transition to the Renaissance, when the revived interest in the authors of Antiquity promoted by Humanism led to the revaluing of its mythological and historical figures.

The book De claris mulieribus (1374) is paradigmatic. In it, the Florentine author Giovanni Boccaccio publishes for the first time in the history of European literature a work devoted entirely to biographies of famous women, including the life stories of figures from Ancient Egypt, such as the goddess Isis, thus making him one of the first European scholars of the period to move away from the Christian theological readings to which these characters were subjected during the Middle Ages.

Indeed, inspired by Latin authors, Boccaccio identifies the Egyptian goddess with the Greek goddess Io, combining their mythological narratives, helping legitimise the former through association with the Greek pantheon. In addition to this, Boccaccio describes Isis as ‘goddess and queen of Egypt,’ going beyond the mythological character to give her a real and historical dimension, inscribed in a human genealogy.

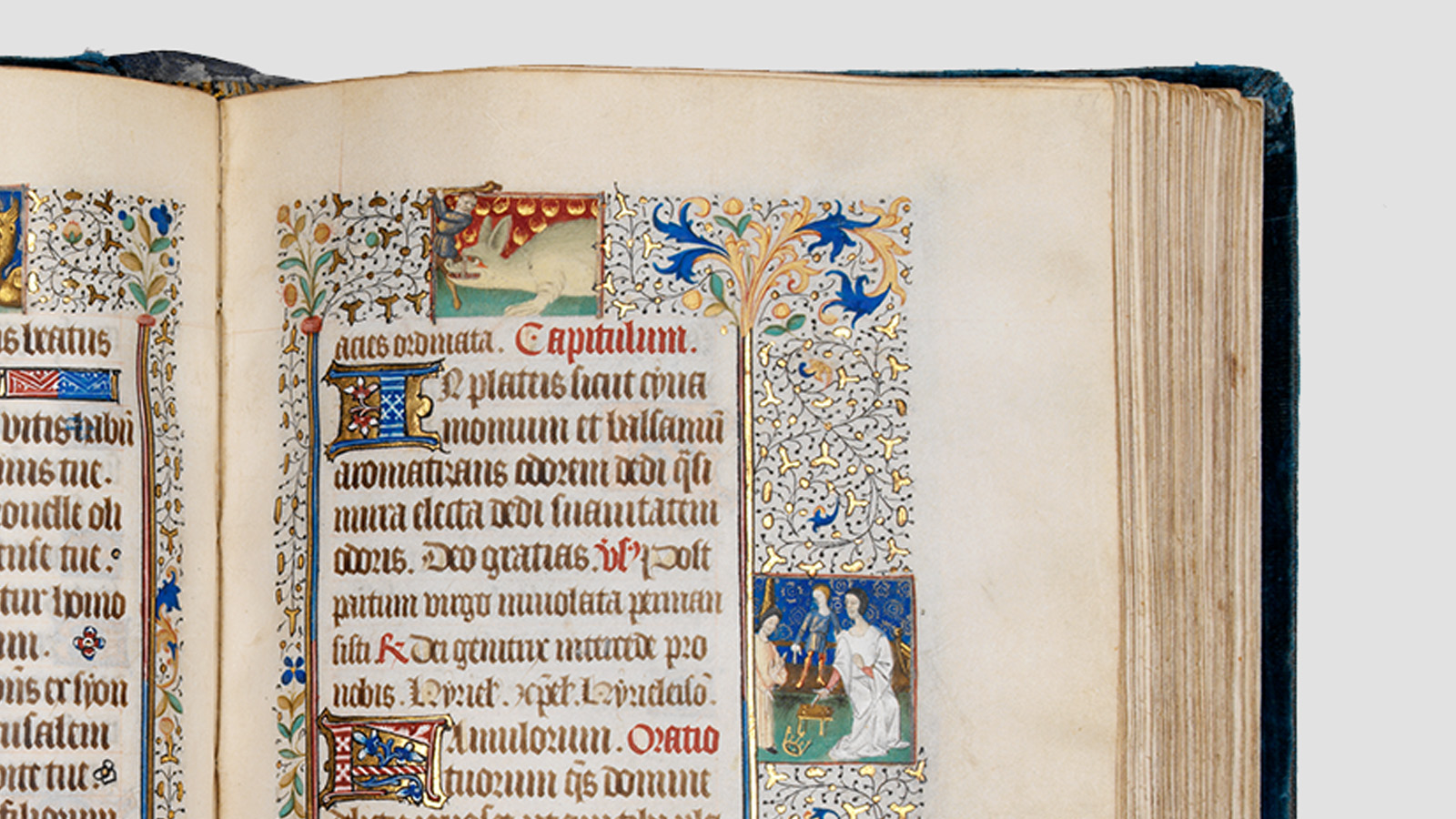

The miniature accompanying Isis’ biography in the manuscript Des clères et nobles femmes belonging to the Gulbenkian Collection (a French translation of Boccaccio’s work) clearly exemplifies the syncretism of these narratives. To the right, the representation of Io on a boat seems to refer to a version of the story of the Greek goddess who, turned into a heifer by her lover Zeus/Jupiter and after enduring countless trials, sails across several seas until she lands in Egypt and recovers her human form, fleeing from the anger of Hera/Juno, Zeus’ wife, who is depicted on the left of the miniature. Next to her, we also see a now-human Isis, goddess and queen of Ancient Egypt, whom the illuminator, unfamiliar with any specific archaeological points of reference, reproduces with clothing that could have belonged to any late-medieval European aristocrat – although the crown on the female figure in the centre has a different configuration to the usual European royal crowns.