Acquisitions from the Hermitage by Calouste Gulbenkian

The Hermitage Museum was founded in 1764 under the Empress Catherine II, known as Catherine the Great (1729-1796). When it first opened its doors to the public in 1852, the Museum housed a collection of some three million pieces, including the largest collection of painting in the world.

On 7 November 1917 (25 October, by the Julian calendar adopted by the Russian Orthodox Church), events took place in Saint Petersburg which led to the founding of the Soviet Union and the communist system.

As a consequence of this new reality, the Hermitage Museum, along with the other buildings in the Hermitage complex, which includes the Winter Palace, were declared by the Soviet authorities to be “State Museums”.

The prestige and size of the Museum’s collections grew when then Soviet State, in the first flush of revolutionary fervour, nationalised a significant number of private art collections previously housed in the countless palaces owned by the imperial family and Russia’s élite.

The Kremlin asked the People’s Commissariat of Foreign Trade for a series of measures to bring in several million roubles/gold for the state coffers, in order to “revitalise and implement socialist industrialisation”.

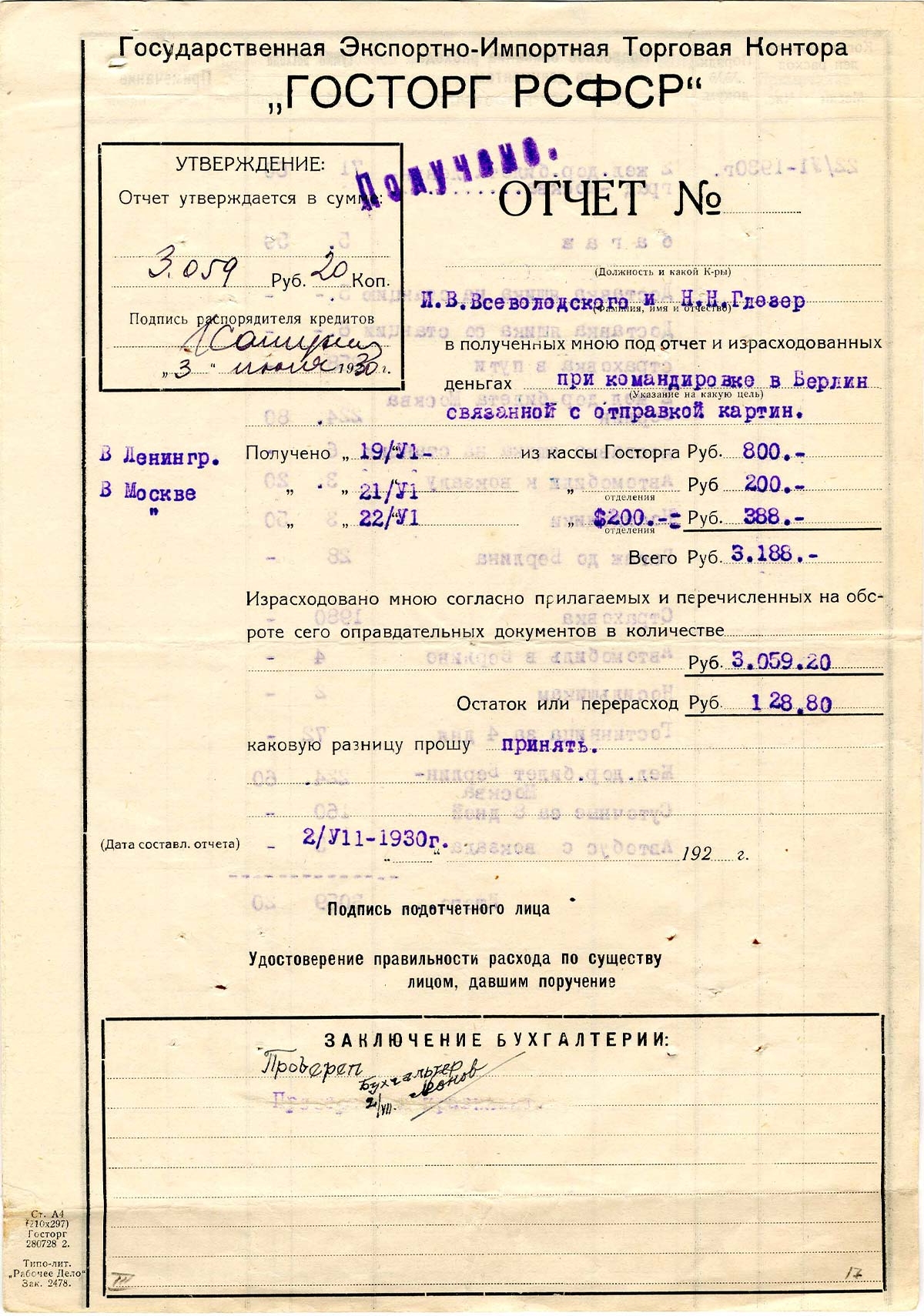

This led to the creation of the ANTIKVARIAT, attached to the RSFSR Gostorg (State Import and Export Agency, founded in 1922), which took direct charge of more than 2,700 paintings (and other artworks) with one purpose in view: sale.

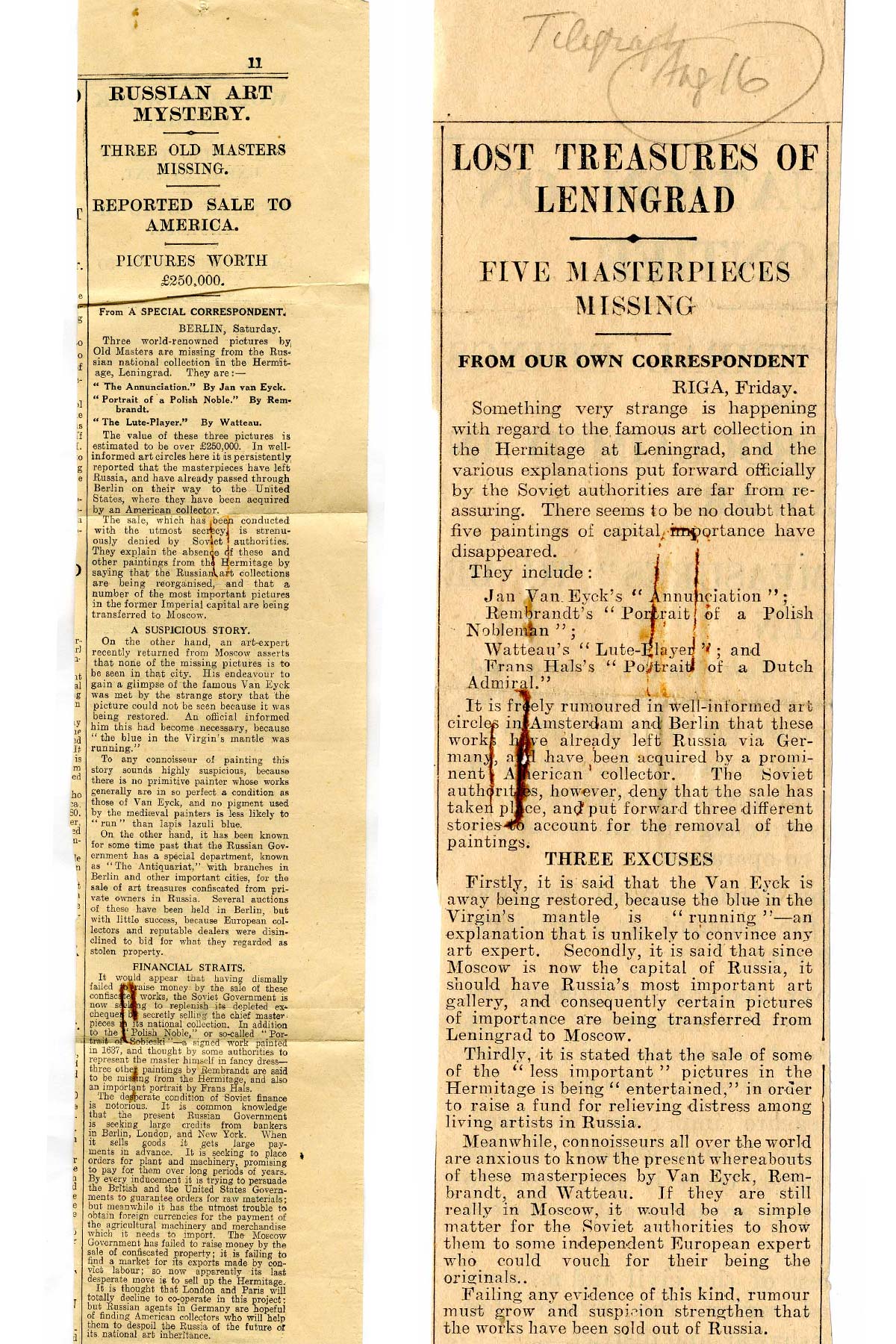

This sell-off of artworks and antiquities belonging to museum collections in the keeping of the State became known to Russian historians as “Operation Hermitage”.

In 1929 alone, some 1,052 objects were sold for a sum of 2,2 million roubles (approximately 1,1 million dollars at that time). Sales appear to have peaked in 1931 (9,5 million roubles), after the economic crisis of 1929, which caused the international art market to crash, contributing to a reduction in both the number and the value of transactions. The year 1934 marked the end of these sales and the “Operation Hermitage”, with the acquisition, by the British Museum, of the Codex Sinaiticus.

The ANTIKVARIAT was wound up in 1937.

It is estimated that the Soviet State succeeded in disposing of around half the works in its keeping to foreign buyers. This amounted to more than 1,400 paintings by artists such as Van Dyck, Rembrandt, Velázquez, Botticelli and Tiepolo from private collections and State museums. Most of these works were sold for prices that would correspond to half, or even a quarter, of their market value.

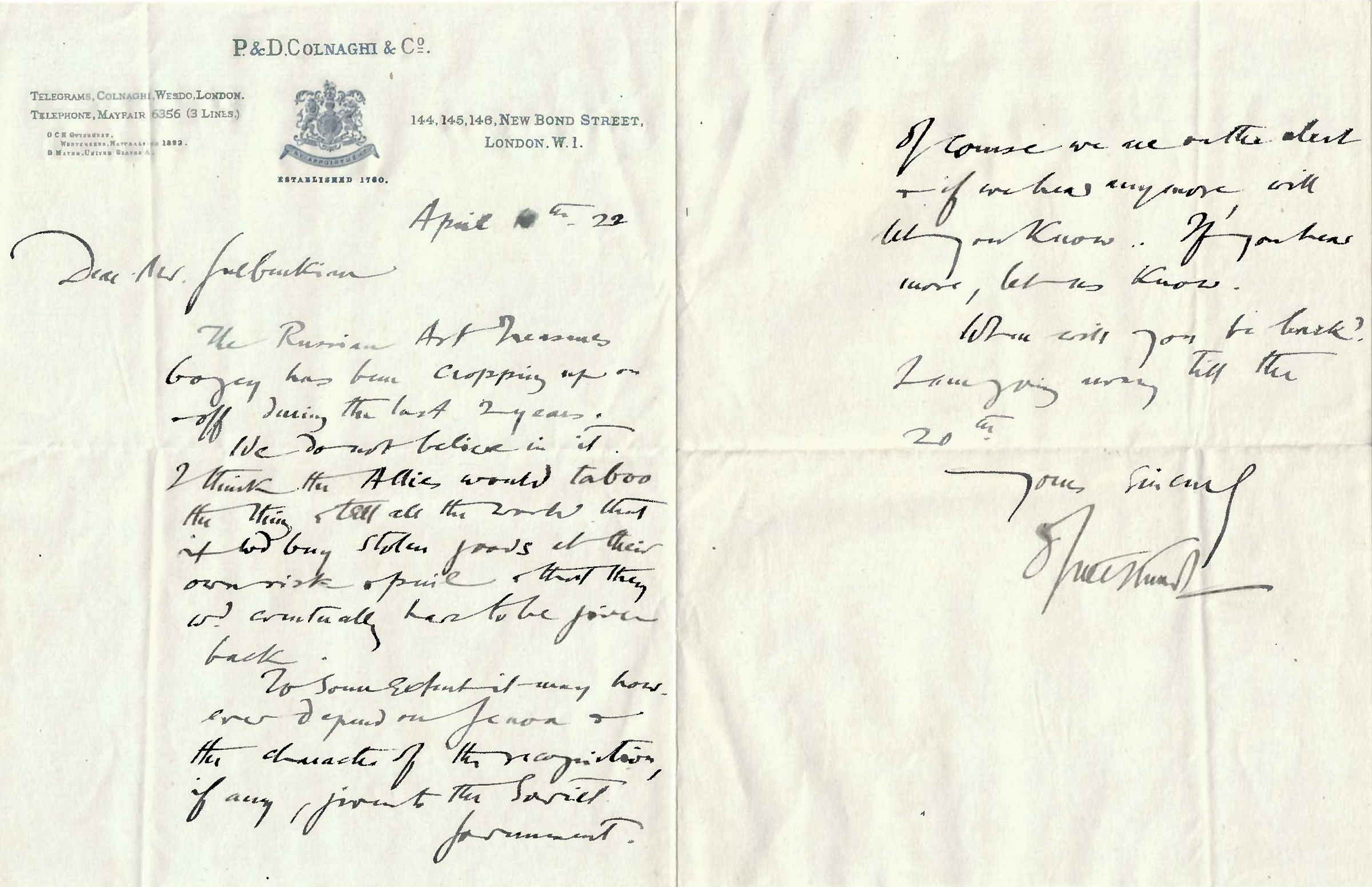

Calouste Gulbenkian’s interest in acquiring artworks belonging to the Hermitage collection dated back to 1922. From then until 1929, when he concluded the first of four purchases, Gulbenkian made a number of approaches to the Russian authorities, in order to discover, assess, select and eventually purchase the works that interested him the most.

His involvement in the Hermitage Operation was not unrelated to the friendship he cultivated with the magnate and philanthropist A. Chester Beatty (1875-1968), with whom he worked, from 1920 onwards, to secure control over mining concessions in Russian territory.

Through his business dealings, Gulbenkian also developed an intricate network of contacts, both personal and professional, with the Soviet authorities, facilitated by his technical expertise in the fields of petroleum, mining and banking. In the eyes of the Kremlin and several key figures in the Soviet nomenklatura, he enjoyed recognised standing and authority. Georges Piatakoff (chairman of the Russian state bank) and other government officials and representatives were fundamental to Gulbenkian’s assiduous lobbying of Moscow.

In July 1930, in a lengthy memorandum sent to Piatakoff, Gulbenkian set out his views on the Hermitage Operation, taking a stand against an endeavour he regarded as harmful to the interests of future generations in Russia: ”(…) vous savez que j’ai toujours maintenu la thèse que les objets qui sont dans vos musées depuis de longues années ne doivent pas être vendus car, non seulement ils représentent un patrimoine national, mais ils constituent encore un grand fond d’éducation en même temps qu’une grande fierté pour la Nation, (…)”

He also drew attention to what he called “(…) la psychologie et la mentalité des dirigeants de crédits à l’étranger (…)”, more interested in personal profit than necessarily in the interests of the Soviet government.

He ends by showing himself to be a shrewd negotiator, declaring: “(…) je continue à le conseiller à vos représentants, de ne pas vendre les objets de vos musées, mais, si vous alliez vendre, de me donner la préférence, à prix égaux, et je leur avais demandé de me tenir au courant des objets que vous désireriez vendre”.

Gulbenkian involved himself directly in the work of consulting and studying the Hermitage catalogues, analysing the proposed lots, assessing and then selecting pieces, while also relying on the expertise and advice of a number of specialists.

The art historian, Schmidt-Degener (1881-1941), and the Parisian jewellers, Marcel and André Aucoc, were involved in the enterprise from the outset. These specialists were entrusted with assessing the pieces in situ (in Leningrad or Moscow) and drawing up detailed reports on the value of the objects and their state of conservation, crucial to a final decision on acquisitions. Gulbenkian was particularly careful concerning issues of authorship and the authenticity of pieces, requiring a meticulously detailed analysis: “Les quatre premiers tableaux doivent être les originaux – ceux que vous avez vu à l’Ermitage – et doivent se trouver en excelente état.”

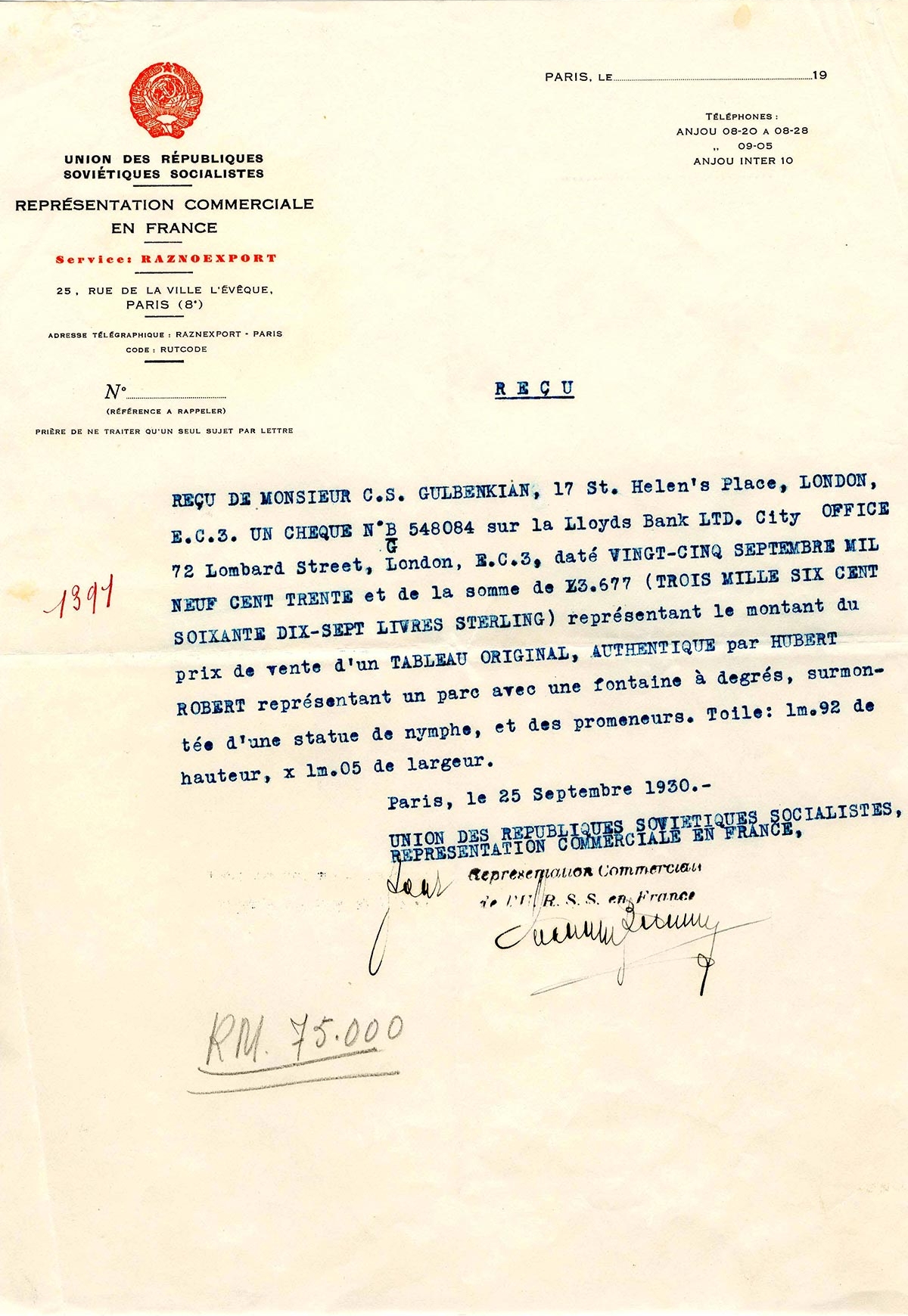

On the basis of the information amassed, Gulbenkian negotiated directly, in Paris, with the leading ANTIKVARIAT officials (with offices attached to the Russian Trade Representation in France), most notably Grigor Samuell, M. Birencweig and N.Toumanoff. The negotiating process almost always entailed last minute changes to the lists of selected works, in addition to bargaining over the prices and terms of sale. The value of the transaction was established between the parties and conditional on the pieces being delivered in a perfect state of conservation.

The pieces acquired by Calouste Gulbenkian fell, essentially, into four categories: jewellery, furniture, painting and sculpture.

In April 1929, Gulbenkian closed the 1ère achat (first purchase), with a price tag of £54,000 sterling, comprising: 24 pieces by the 18th century silversmith, François-Thomas Germain; a Louis XVI table; two paintings by Hubert Robert, Le Bosquet des Bains d’Apollon and Le tapis vert, a painting by Dierick Bouts, Annunciation.

The 2ème achat was concluded in February-March 1930, adding new works worth £155,000 to Gulbenkian’s collection: 15 pieces of silverware and a painting by Peter Paul Rubens, Portrait of Helena Fourment.

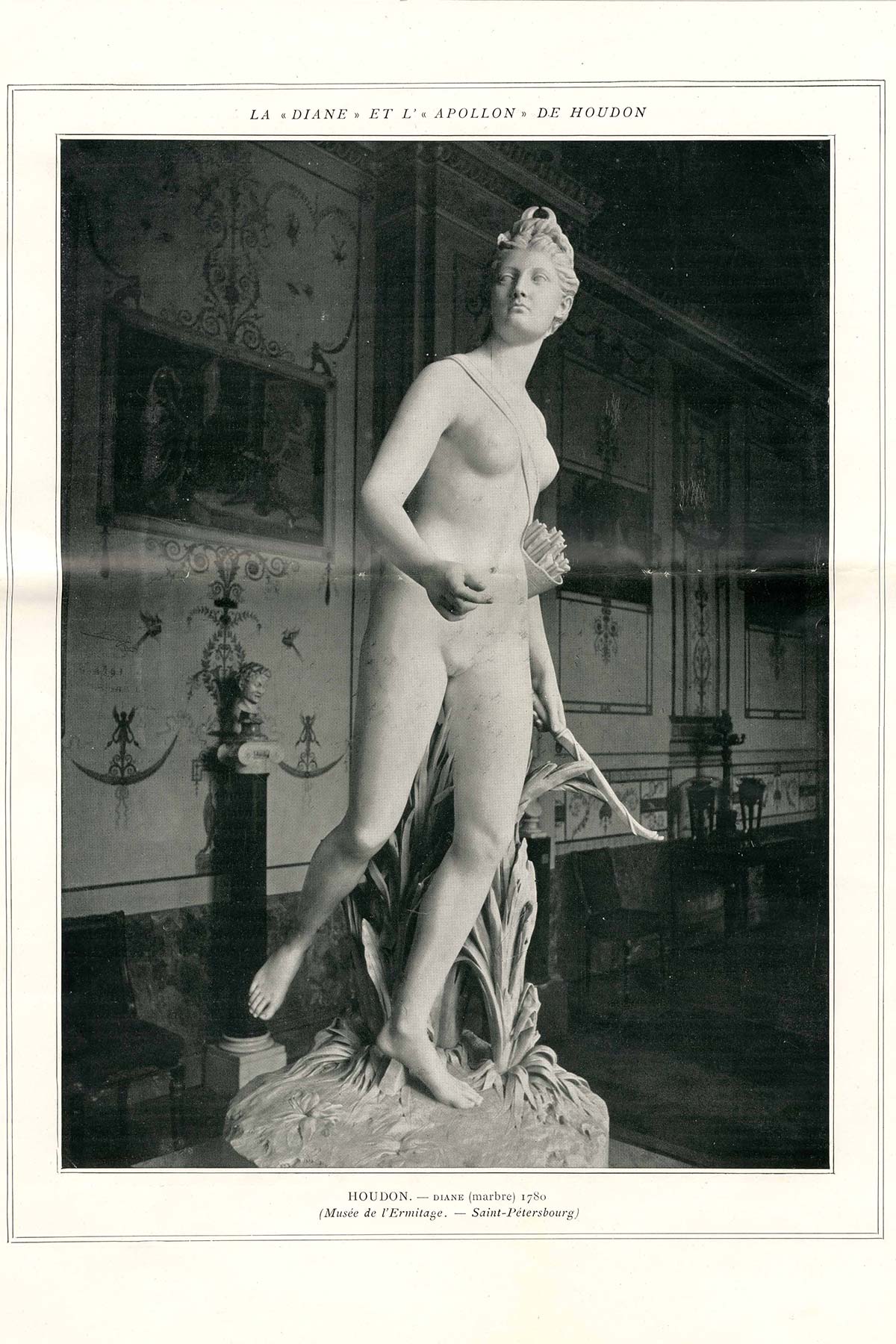

The 3ème achat was also closed in 1930, in June, with a value of £140,000. This included: 5 paintings by Rembrandt Titus and Pallas Athena, and by Lancret, Watteau and Ter Borch, and the sculpture Diana, by Houdon.

The final purchase, or 4ème achat, dated from October 1930 and consisted of Portrait of an Old Man, by Rembrandt, bought for £30,000.

Gulbenkian demanded the highest standards in packaging, stowing and transporting the pieces, once again demonstrating a full understanding of the technical issues involved.

Mindful of the vast distance that the objects would have to travel and the vicissitudes to which they would consequently be subject on their journey, he sought to ensure that the essential steps were taken to reduce the risks involved in transport: “Il est bien entendu que vous prenez bonne note de mes recommendations d’employer un nombre suffisant des caisses, afin de chacune ne contienne q’un nombre restreint de pièces ceci dans le but d’amoindrir les risques de transport.”

Although the Soviet authorities were responsible for packaging and transporting the pieces, Gulbenkian sent trusted art handlers (such as the French specialist, Edouard Leblond) to Leningrad to oversee the packaging process.

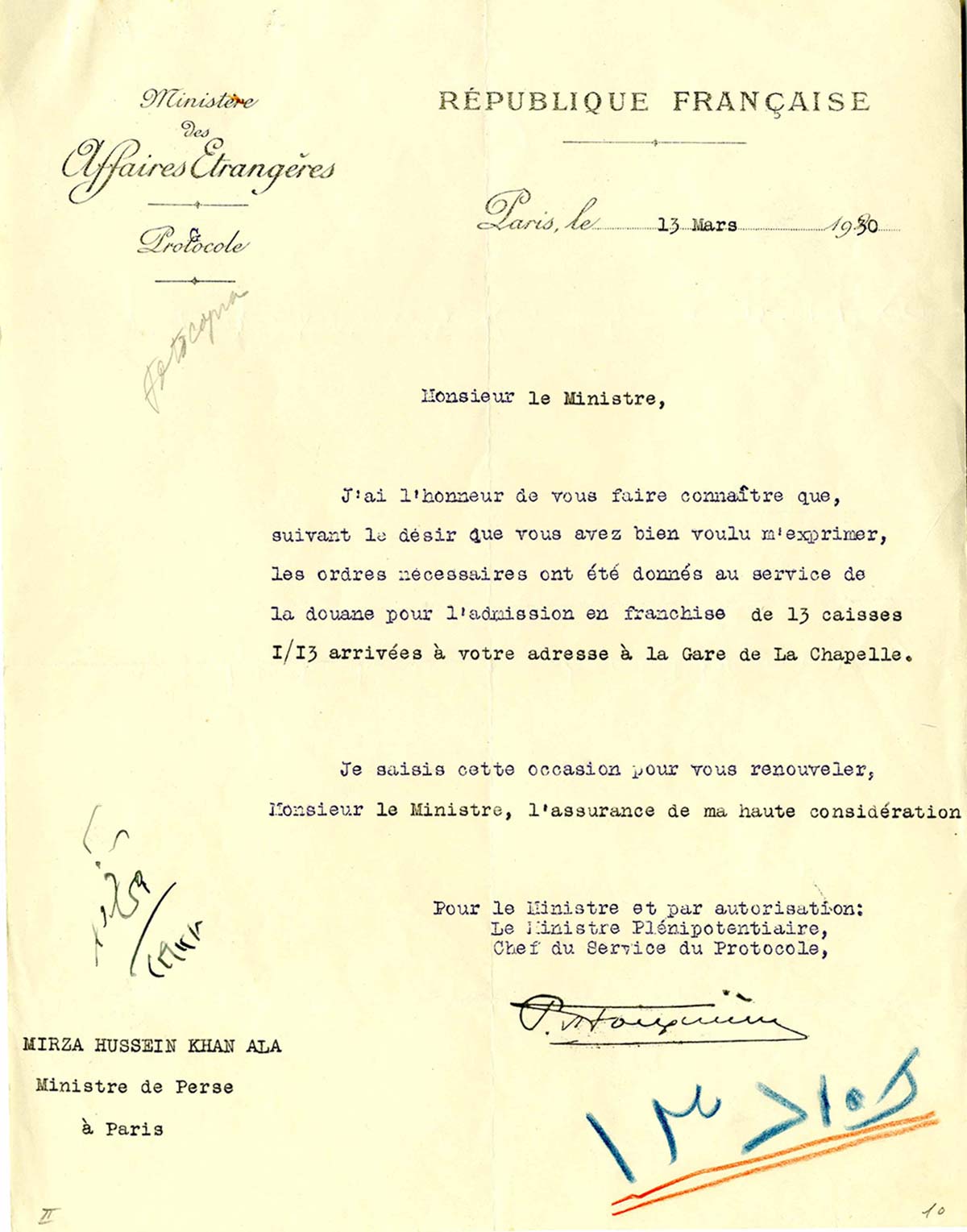

The acquisitions travelled from Leningrad via Germany or London, by rail or sea. In order to avoid difficulties at customs, the containers were addressed to the Persian Legation in Paris, represented by Calouste himself (at that date, Financial Advisor to the Legation), an arrangement that was cleared by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Persian Minister Plenipotentiary in Paris.

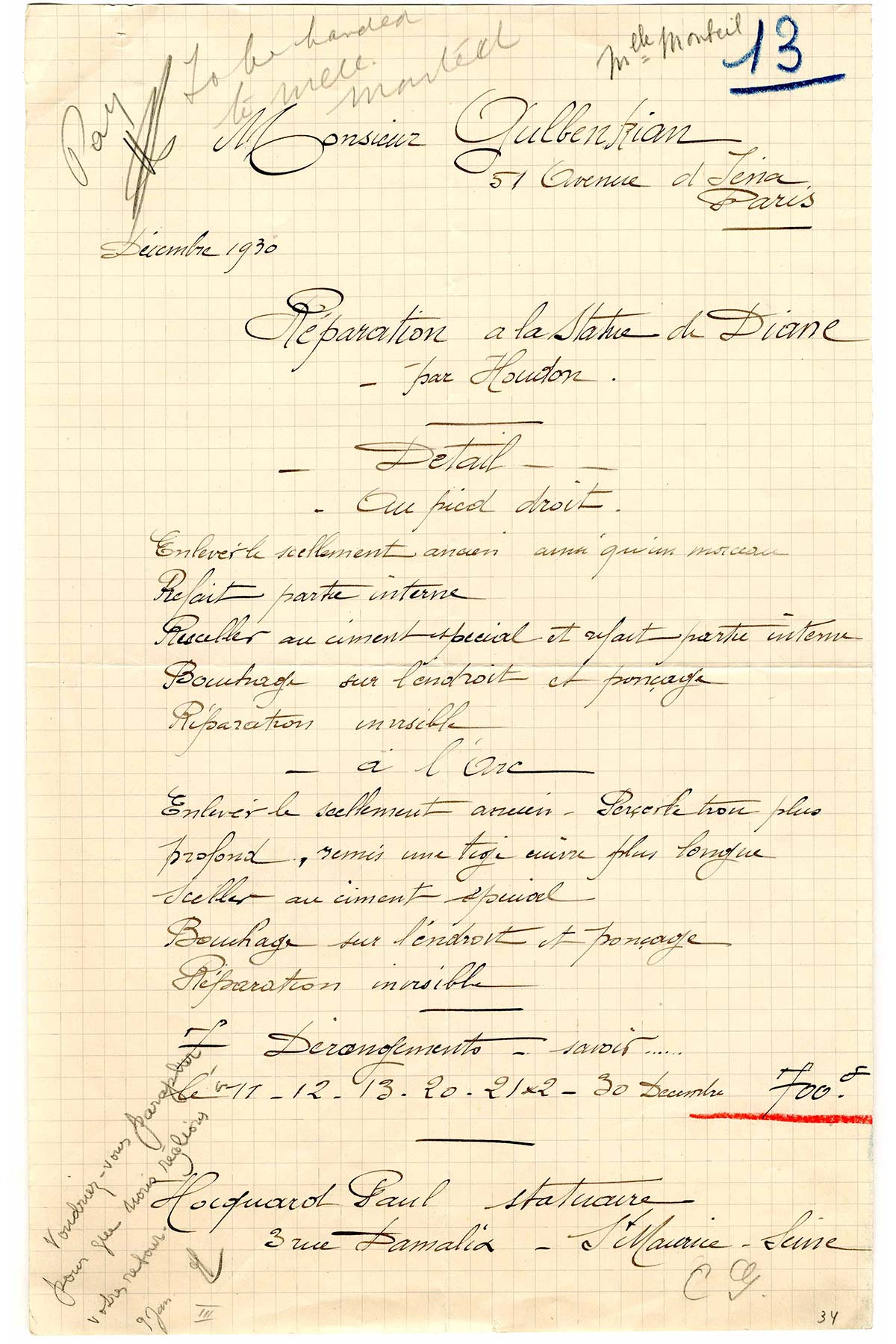

The containers were meticulously checked in the presence of the customs authorities, by Gulbenkian himself or representatives he appointed for this purpose, such as the German art dealer, Francis Zatzenstein (1897-1963). The purpose of this inspection was to ensure, prior to payment, that the works remained in an excellent state of conservation and, more importantly, that they corresponded to the pieces that left the Hermitage a few days earlier.

The additional costs involved were divided on a simple basis: freight, charges and customs duties relating to the territory of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics were borne by the Soviet government, and all costs incurred outside Russian territory were shouldered by Gulbenkian.

Payment was made by cheque, on delivery of the piece, in other words, in person: “Inutile de vous [Aucoc] recomender de prendre toutes les précautions possibles pour la protection du chèque ci-inclus que vous emporterez avec vous afin qu’il n’arrive aucun accident. J’ai préféré vous donner ce chèque au lieu de le faire passer par une Banque afin de hâter l’opération.”

The Gulbenkian Archives in the Foundation’s keeping, and in particular the documents from London and Paris, exhaustively record the entire operation of acquiring artworks from the Hermitage. A reading and analysis of the documents collected in the “Dossier Russie” enables us to map out the whole bureaucratic, financial and logistical process, bringing us closer to the collector himself and his modus operandi in the world of business and art, confirming one of his best known maxims: “Only the best is good enough for me…”

From the Archives

Significant moments in the history of Calouste Gulbenkian and the Gulbenkian Foundation in Portugal and around the world.