19 Dec / Unravelling the timeline

What is “new” about a series of dances that span the Portuguese 20th century? In what ways do the history of dance and the history of the century intersect?

This session takes as its point of reference the first and last rooms of the exhibition – whose works and organising principles it will examine in more depth – in order to explain the very research that informs the dance not dance programme.

Thus, by discussing works by Vera Mantero, Francisco Camacho, Almada Negreiros, Paula Massano, Dança Grupo, Madalena, Vitorino Fernando Lopes Graça or the Gulbenkian Ballet, present in these two rooms, issues related to dance experimentation, improvisation, composition – and the body – are addressed. It is, after all, the unusual emergence of the body in the works of the young Portuguese New Dance choreographers Francisco Camacho and Vera Mantero that leads Alexandre Melo to wonder whether the Portuguese have a body, given its absence in the prevailing discourses.

20 Dec / Individual and collective freedom of body and mind

The idea of a “free” dance – in other words, dance understood as a way of expressing a freedom of spirit that manifests itself in and through the body – spanned the 20th century. But... what can training in and for freedom be? Individual and collective freedom?

This session, focusing on the second and fourth galleries of the exhibition – whose works will be examined in more depth – brings together figures such as Isadora Duncan, Josephine Baker, Ruth Aswin or Valentim de Barros, and works by Margarida Bettencourt, Joclécio Azevedo, Mónica Lapa, Vera Mantero, Ângela Guerreiro, Ana Borralho and João Galante, Miguel Bonneville or Miguel Pereira. In this way, individual and collective ideas of the body and freedom are problematised, highlighting the ways in which the eventual presentation of the “I” outlines them, but also their potential.

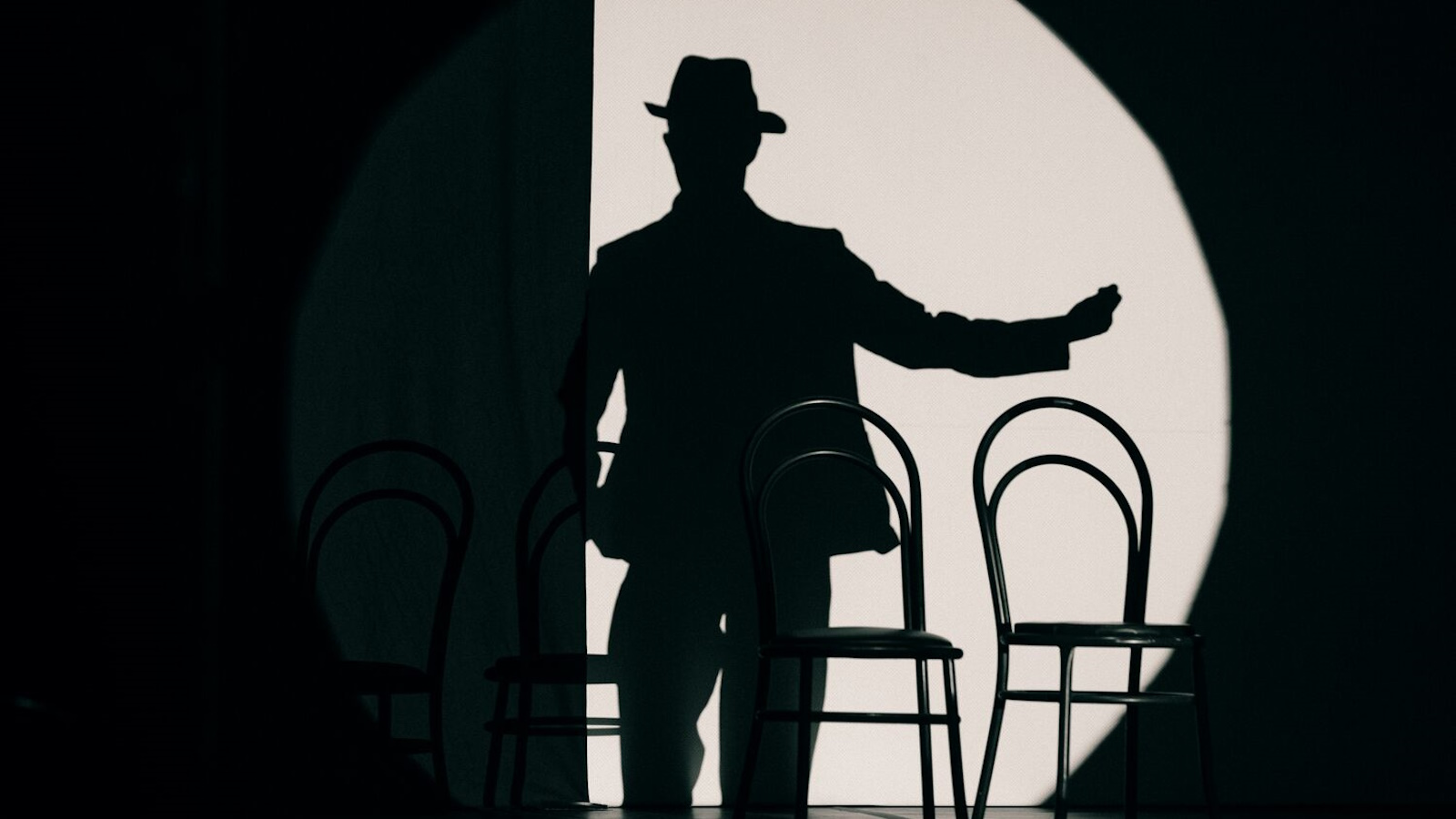

02 Jan / Il faut danser Portugal

This session questions the terms “portugality” and “dance” as dreamt up by power and sketched out by artists. Looking at the pieces in the exhibition gallery with the same motto, we analyse works by António Olaio, Sílvia Real, Vânia Gala, Francisco Camacho, António Tavares, Paulo Ribeiro or Rui Nunes, placing them in dialogue with choreographies by Bailados Portugueses Verde Gaio and Círculo de Iniciação Coreográfica and with texts by Tomás Ribas, António Ferro, José Sasportes, José Blanc de Portugal or Margarida de Abreu. Can the contrast between these works offer a glimpse of the many other dances that, calling themselves or being called “Portuguese” by others, embody a culture that is as iconoclastic as it is situated and limited?

In 1984, António Olaio presented Il faut danser Portugal as part of the Portuguese Performance Festival organized by Egídio Álvaro at the Centre Pompidou on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the Portuguese Revolution. In 1948, Francis choreographed Nazaré, one of the most emblematic works of the Bailados Portugueses Verde Gaio, from which he would leave for good shortly afterwards, and one of the few to have an almost complete record, adapted for the camera. How does the portugality parodied by Olaio in 1984 correspond to that stylized by Francis in 1948? How do they both contribute to a study of the relationship between choreographic production in Portugal in the 20th century and ideas of national identity or its critique?

03 Jan / The Gulbenkian Effect

In this session, visiting both the history of the Gulbenkian Ballet and ACARTE and the career of its guardian, Madalena de Azeredo Perdigão, discussing key moments and pieces, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation's role in the national dance scene is discussed. Between the creation of the Grupo Gulbenkian de Bailado in 1965 – later Ballet Gulbenkian – and its demise in 2005, Portugal produced an incomparably greater number of pieces than in any previous period, and the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation's Service for Animation, Artistic Creation and Education through Art (ACARTE) has been active for a long time, with a frenetic updating of the repertoire, finally bringing the country's choreographic production into line with trends in the field. Whether it was through the Gulbenkian Ballet, which included protagonists from the New Portuguese Dance, or ACARTE, which fostered the break they had made, the dance scene changed radically in the country.

09 Jan / These bodies that occupy us

This session questions the very different ways in which a group of works in the exhibition's sixth gallery – by, among others, João Fiadeiro, Mário Calixto, Mikaella Dantas, Diana Niepce, Rita Marçalo, Luís Guerra, Tânia Carvalho, Clara Andermatt, Sofia Dias and Vitor Roriz – have been proposing other understandings of the body and, with it, of the body-world relationship. Capable of becoming another body, far from canonical ideas of dance and its prescriptive character, as well as techniques for “normative” and virtuous bodies, the body without organs of New Portuguese Dance is made of powers. It is a body in becoming, searching for itself in its openness to difference, with uncertain contours and in reciprocal affectation with what it encounters each time. It can become a thing – diluting subject and object in other relationships – or desire – an abstract engine from which worlds emerge. It is a generative body of images, problems and concepts, but also of other ways of inhabiting the world and, with this, the theater where dance and the public meet.

10 Jan / Those who don't dance don't know what's going on

Reviewing the previous sessions, and focusing in particular on chronology, this session questions the present through various readings of the century. In what ways do themes and problems that we encountered in the 1910s and 1920s, or even the 1950s, resurface today? What is the relationship between the April Revolution of 1974 – which celebrated its 50th anniversary – and the New Portuguese Dance? How do anachronisms and tensions crystallised by 48 long years of dictatorship and repression persist today? And what movements, gestures and sounds of freedom can be glimpsed in these dances? How can we apprehend through the dances on display the time that is theirs and the many disputed times that are to be found in them?