Egypt: the nearly distant land

Sarah Nagaty

50% – under 30 years and over 65

Free admission – Sunday after 14:00 / Students on Fridays and Saturdays after 18:00

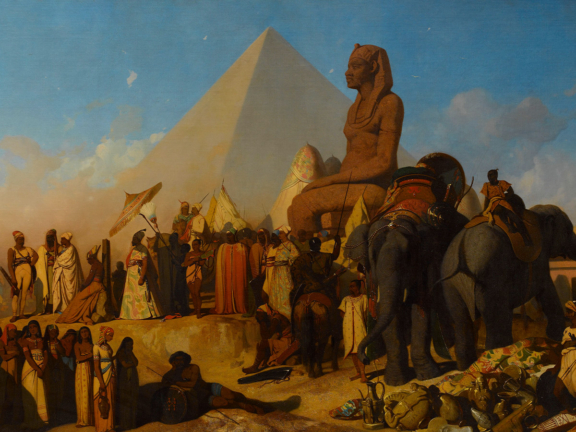

Superstar Pharaohs is conceived around the figure of the Pharaoh and the place occupied in our imagination by Ancient Egypt, through 5,000 years of history, from antiquity to the present day. It aims to reflect on the popularity of the historical and sometimes mythical figures of the Pharaohs.

These also serve as a parable to illustrate the nature and channels of ‘celebrity,’ highlighting its ephemeral, changeable side, not always associated with historical recognition. Khufu, Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ramesses and Cleopatra are still familiar names, thousands of years after the death of these Pharaohs. But, nowadays, who can remember Teti, Senwosret or Nectanebo?

From Egyptian antiquities to pop music, incorporating medieval illuminations and classical painting, this exhibition brings together different kinds of objects, such as archaeological pieces, historical documents and works, and contemporary objects.

On display will be around 250 pieces from important European collections, among them the British Museum, the Musée du Louvre, the Museo Egizio (Turin), the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford), the Musée d’Orsay (Paris), the Mucem – Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée (Marseille), the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal (Lisbon).

The exhibition also provides an opportunity to reflect on the Egyptian art section of the Gulbenkian Museum and on the relationship that collector established with Egyptologist Howard Carter, his advisor in most of his purchase, framed by the commemorations of the centenary of the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb by Howard Carter and the bicentenary of Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion first deciphering hieroglyphs.

Download the Gulbenkian Museum App to access a free audioguide.

Ancient sources provide plenty of evidence of the popularity that some pharaohs enjoyed after their death, often very locally, sometimes over several centuries or even millennia.

The Ancient Egyptians thought that an individual would survive in the afterworld for as long as their name was kept alive in speech or writing and their image was preserved. The king therefore prepared for his own funerary cult by building temples and statues bearing his name, inscribed in a oblong frame known as a cartouche. He also sought blessings from his deified predecessors.

Above all, he had to work visibly on behalf of the community and inspire the love of his subjects, even after his death. However, the pharaohs known today were not always the most deserving in this respect.

The pharaoh’s mission was to preserve the perfect order of the world as it existed at the moment of its creation. This meant he had to battle against the forces of disorder, especially by extending or reinforcing borders to keep away neighbouring populations. By controlling peripheral territories, he also brought riches to Egypt, which allowed him to feed his people and build temples filled with offerings, statues and precious furnishings. The great warriors and builders, such as Senwosret I and Senwosret III, Thutmose III and Ramesses II, were those whose fame has lasted longest.

Royal monuments, temples, pyramids and colossi have had a lasting impact on the very flat landscape of the Nile valley. They have dominated the horizon every day for countless generations, and people have long continued to remember the pharaohs who built them. Unlike the effigies of gods hidden away in the temples, the gigantic statues visible to the faithful were venerated, playing an important role in perpetuating the memory of the kings they depicted. Inspired by his predecessors, Ramesses II was well aware of this when he organized his own deification.

Pharaonic monarchy was expected to be eternal and uninterrupted. The king therefore took care to appear as a worthy successor to his most illustrious predecessors: he dedicated monuments to them and took inspiration from their images and titles. He established memorial cults which employed large numbers of workers, who maintained a privileged link with these royal ancestors, as is sometimes reflected in the names they gave to their children.

King Ahmose, his wife Ahmose-Nefertari and their son and heir Amenhotep I reunified the kingdom after more than a century of division and built or restored many monuments. As a result, they continue to be remembered as the benevolent founders of a prosperous era. In Thebes (Luxor) they became local patron saints, with an influence on daily life and on the afterlife. Their statues were worshipped in votive chapels and consulted by oracles when processions took place.

The Egyptians also erased the memory of some pharaohs, omitting them from royal lists, cancelling out their names and destroying their images. Troublesome kings thus saw their reign or even their very existence wiped out. This fate befell the female pharaoh Hatshepsut, who created a risky precedent for the transmission of power, as well as Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti, who attempted a radical reform of religion and power, and their immediate successors such as Tutankhamun.

The Christianization of Egypt at the beginning of the present era signalled the end of Pharaonic civilization, whose earliest history was gradually forgotten. For more than a thousand years, from the Middle Ages to the nineteenth century, Europe and the Arab world only remembered the pharaohs mentioned by Greek or Latin historians such as Herodotus, Diodorus of Sicily and Aelian. Authors such as these gleaned distorted memories of ancient kings from Egypt and from the literature of the Mediterranean, as did the Biblical and Islamic traditions. These figures inspired artists and scholars on both sides of the Mediterranean. They were used as political or moral models – or examples not to follow.

Because they enjoyed sustained relations with the Greeks, the pharaohs of the seventh and sixth centuries BCE are often mentioned in classical literature. Psamtik I used Greek mercenaries while Amasis granted significant concessions to Aegean Sea merchants. From the Renaissance onwards, artists were inspired by Hellenic texts describing these reigns, especially accounts of Amasis taking the throne and legendary stories of Psamtik.

The Alexander Romance, a fictional account produced by Alexander the Great’s successors in Egypt, claims that Alexander was not the son of the Macedonian king but of Nectanebo, the last pharaoh born on Egyptian territory. According to the tale, this king with magic powers fled his kingdom when it was invaded by the Persians, seduced the queen of Macedonia and conceived with her the hero who in turn conquered Egypt and reclaimed his heritage. Alexander was a popular figure in the Roman, Byzantine and Islamic worlds: in his slipstream, the distorted memory of the last king of Egypt before Hellenic influence, survived into the Middle Ages.

The image of Cleopatra transmitted by Roman historians was of a promiscuous and ambitious seductress, embodying the dangerous charms of the Orient. Her legendary suicide by snakebite was a favourite subject for Christian artists, who saw it not only as a heroic act but also as an opportunity to paint naked flesh, which was censured. Conversely, in the classical Arab world, Cleopatra was regarded as a wise queen, a great builder and a fine administrator dedicated to the defence of her kingdom.

Originating from late Egyptian narratives reinterpreted by the Greeks, this mythical figure, more or less inspired by various sovereigns in Egyptian history, combined attributes of the pharaohs Senwosret I, Senwosret III and Ramesses II. He is given the image of a fearsome conqueror, forerunner of Alexander and Napoleon, and of a great legislator and builder: numerous colossi have been attributed to him thanks to the writings of Greek and Roman historians. In scholarly tradition of the modern era, Sesostris was the model pharaoh, and his name immediately evoked the power, antiquity and exoticism of Ancient Egypt.

The kings of Egypt most often mentioned in Europe and in the Islamic world, from the Middle Ages to the present day, are undoubtedly the sovereigns whose name simply appears as Pharaoh in the Bible and Firaun in the Qur’an. One of these kings listens to Joseph/Yusuf and raises him to the rank of minister. He comes across as a hospitable and benevolent foreigner, especially for the Jews of the diaspora. Another opposes God and his envoy Moses. He embodies arbitrary oppression and impious tyranny for all cultures that relate to the Exodus.

Egyptologists began to understand how to read hieroglyphics in 1822. Since then, the pharaohs have gradually emerged from obscurity. The media and museums, flourishing in the twentieth century, turned them into international stars and the old literary figures were discarded. Ramesses, Akhenaten, Nefertiti and Tutankhamun joined Khufu and Cleopatra as the heroes of new popular accounts inspired by our fascination with Egypt. With the industrialisation of consumer products and advertising, they also became selling points that stirred the imagination of buyers. In parallel, their images and names had a role in defining identity, especially for Egyptians. The image of the pharaohs was then disseminated across an infinite variety of media: news, films and photos, advertising products and manufactured goods, popular imagery and works of art

In the light of texts which could now be understood, Ramesses II, whose achievements had long been attributed to the legendary Sesostris, became once more the model pharaoh. His name became familiar with the Egyptomania and Orientalism of the late nineteenth century and the idea began to spread that he was the Pharaoh of Exodus, a powerful opponent of Moses and God. In the 1960s, the spectacular rescue of his temples at Abu Simbel meant that his monumental image featured regularly in the press and on television.

Archaeology between the 1880s and 1910s revealed the figures of Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti, considered the inventors of the single god. The apparently modern quality of their portraits enchanted the West. In 1922, the British archaeologist Howard Carter discovered the tomb of their successor, Tutankhamun, and his fabulous treasure. With the expansion of the press and advances in photography and film, the event was announced all over the world. The new fame of these forgotten kings was given added weight by popular exhibitions.

After the nationalist movement resulted in Egypt emerging from British rule in the 1920s, the country promoted the pharaohs as patriotic emblems. Even though Islam remained the main model, these ancient figures represented an opportunity to look beyond individual and local identities. They became sources of inspiration for the arts, references for political comparison and even brands, commercial products aimed at both tourists and Egyptian citizens.

Technical advances have meant that information and, in some cases, stereotyped images of the great pharaohs can be propagated around the whole world. They have become icons accessible to everyone, symbolizing everything that is fascinating about Ancient Egypt: longevity, personal power, the quest for immortality, precious materials, biblical references, mystery and the sultry climate. Their supposed virtues and vices have inspired authors, while their fame appeals to the public and increases consumer confidence.

Since the twentieth century, scholars seeking to reappraise the history of African peoples, which was tarnished by the slave trade and colonialism, have claimed that the pharaohs were Black. In Africa and African diasporas, creative artists, well-known hip-hop, rap and rhythm & blues musicians, as well as ordinary citizens, have seized upon the pharaonic icons, making them guiding lights for their Black identity and emblems of Black Pride.

While, prior to the cathedrals of the Middle Ages, Khufu’s 147-metre-high pyramid was the tallest monument on Earth, there are no surviving images of this pharaoh – apart from one modest 7 cm ivory statuette, kept in Cairo.

At the head of a prosperous empire, Ramesses II made himself represented as a god, treated on an equal footing with the other deities. On some monuments, he is seen making offerings to his own image and statues of himself.

After a period during which the kingdom was divided, Ahmosis reunited Egypt in the 16th century BCE by expelling the rival Hyksos dynasty from the north of the country. This feat was glorified in the 20th century in an Egypt that was colonized and subjected to imperialisms, notably by the novelist Naguib Mahfouz.

The immediate successors of the young pharaoh destroyed, and usurped, his monuments by replacing his names in inscriptions with their own. They wanted to erase all traces of his reign because he was the son of Akhenaten, the iconoclastic pharaoh.

A legend forged in Alexandria told that the great Greek conqueror was not the true son of the king of Macedonia, but the son of his wife and the pharaoh Nectanebo, who pretended to be a god to seduce her. This legend is recounted in many medieval manuscripts that trace the life of Alexander.

… at least not in the sense that we understand it today: it is an official and idealised image, a geometrically perfect and symmetrical face, built according to the system of measurements of the ancient Egyptians. We know of other representations of the queen where she has exactly the same features as her husband, Pharaoh Akhenaten. Her true appearance is actually unknown to us.

When, in 1779, the Dutch entomologist Pieter Cramer classified exotic butterflies, he called a large black and green species Parides sesostris. He borrowed this name from the legendary Egyptian king Sesostris, whose name was synonymous with grandeur and majesty in the 18th century.

On several occasions, the Bible and the Qur’an use the ancient royal title ‘Pharaoh’ as the name for several unidentified rulers of Egypt, including Moses’s foe. This pharaoh symbolizes the tyranny and ungodliness that God punishes.

The regime of President Gamal Abdel Nasser launched production of many Egyptian-made products that were given the names of famous pharaohs and queens. In doing so, he sought to promote Egyptians identity and national pride.

Khufu reigned from around 2635-2605 BCE, and Cleopatra from 51 to 30 BCE, about 2,600 years later. In 2022, it has only been 2,052 years since Cleopatra died. These few figures give an idea of the longevity of the civilization of the pharaohs, during which the memory of great kings like Khufu has endured.

Guided tour and conversation: Egypt – the nearly distant land

With Sarah Nagaty, in English

Fri, 24 Feb; 03 Mar / 19:00

More info

Guided tour: Superstar Pharaohs

With Carlos Carrilho, Filipa Santos e Raquel Feliciano, in Portuguese, English and French

More info

Self-guided tour: Superstar Pharaohs

More info

Tutankhamun and Carter: Assessing the Impact of a Major Archaeological Find

Thu, 16 Feb and Fri, 17 Feb

More info

In the Lands of the Pharaohs. Representations of Ancient Egypt in the cinema

06 Jan – 19 Jan 2023

Cinemateca Portuguesa

More info

Calouste Gulbenkian and Egypt

Art Library Hall

16 Nov 22 – 06 Mar 23

More info

Frédéric Mougenot – Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille

João Carvalho Dias – Calouste Gulbenkian Museum