Event Slider

Date

- Fri and Sat,

Location

Main Gallery Calouste Gulbenkian FoundationThis exhibition is dedicated to Georges Remi, the multi-talented artist known as “Hergé”.

Co-produced with the Hergé Museum of Louvain-la-Neuve, the show brings together an important selection of documents, original drawings and various other works by Tintin’s creator, through which visitors can decipher the art behind this creative genius who deployed every means available to his compositions, from illustration to cartoons, advertising, print, fashion design and visual arts.

Inspired by several artistic movements of his time – from pop art to abstract art through to minimalism –, this self-taught artist was also interested in ancient civilisations and the so-called “primitive arts”.

What makes Hergé's art truly unique and distinct from other cartoonists is his extraordinary capacity to represent reality in such a creative but familiar way that readers can easily see themselves in this universe built from scratch. With simple lines made with impressive precision, under the banner of his inimitable "clear line", Hergé created emblematic characters that embody society's great values.

This exhibition is a unique opportunity for visitors to discover some of the treasures from the Hergé Museum: original storyboards, paintings, photographs and archive documents.

It also provides an occasion to reveal a lesser-known artistic facet: his brilliant career as an advertising and graphic designer, showcased by his ingenious posters.

Delve into the many dimensions of this landmark artistic figure of the 20th century!

Topics

Hergé, the art lover

Novelist of the image

Tipping point

A paper family

Coeurs Vaillants Magazine

The art of advertising

Lesson from the East

The birth of a myth

-

Greatness of minor art

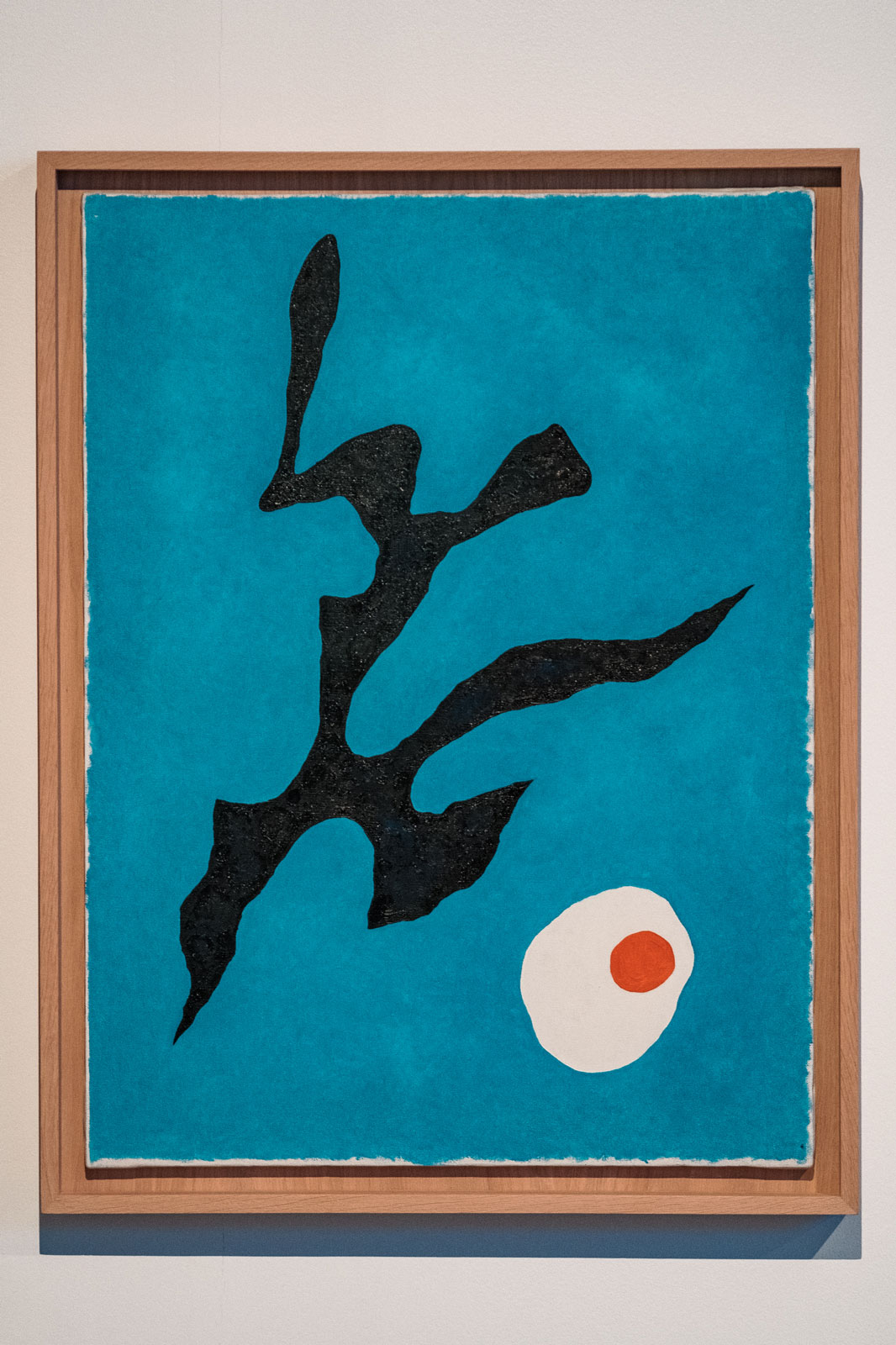

The little regard for comics affected Hergé, whose internationally acclaimed work sparked much interest, but struggled to be recognized as real art. Today, this exhibition celebrates the great artist he was by journeying back to the roots, and offers visitors the opportunity to explore certain obscure aspects of his personality, such as his dabbling in painting in the early 1960s and the fascination he had for the art of his time, the most modern of all.

Hergé, Composition sans titre, c.1960 © Pedro Pina

Hergé, Composition sans titre, c.1960 © Pedro Pina

Hergé, Composition sans titre, c.1960 © Pedro Pina -

-

Hergé, the art lover

Way before his personal encounter with modern art, Hergé had become familiar with artistic movements of all origins and eras. Right from the start of his career at Le Vingtième Siècle newspaper, the young man came into contact with articles on paintings and sculptures by his contemporaries, but also art movements of the recent and distant past.

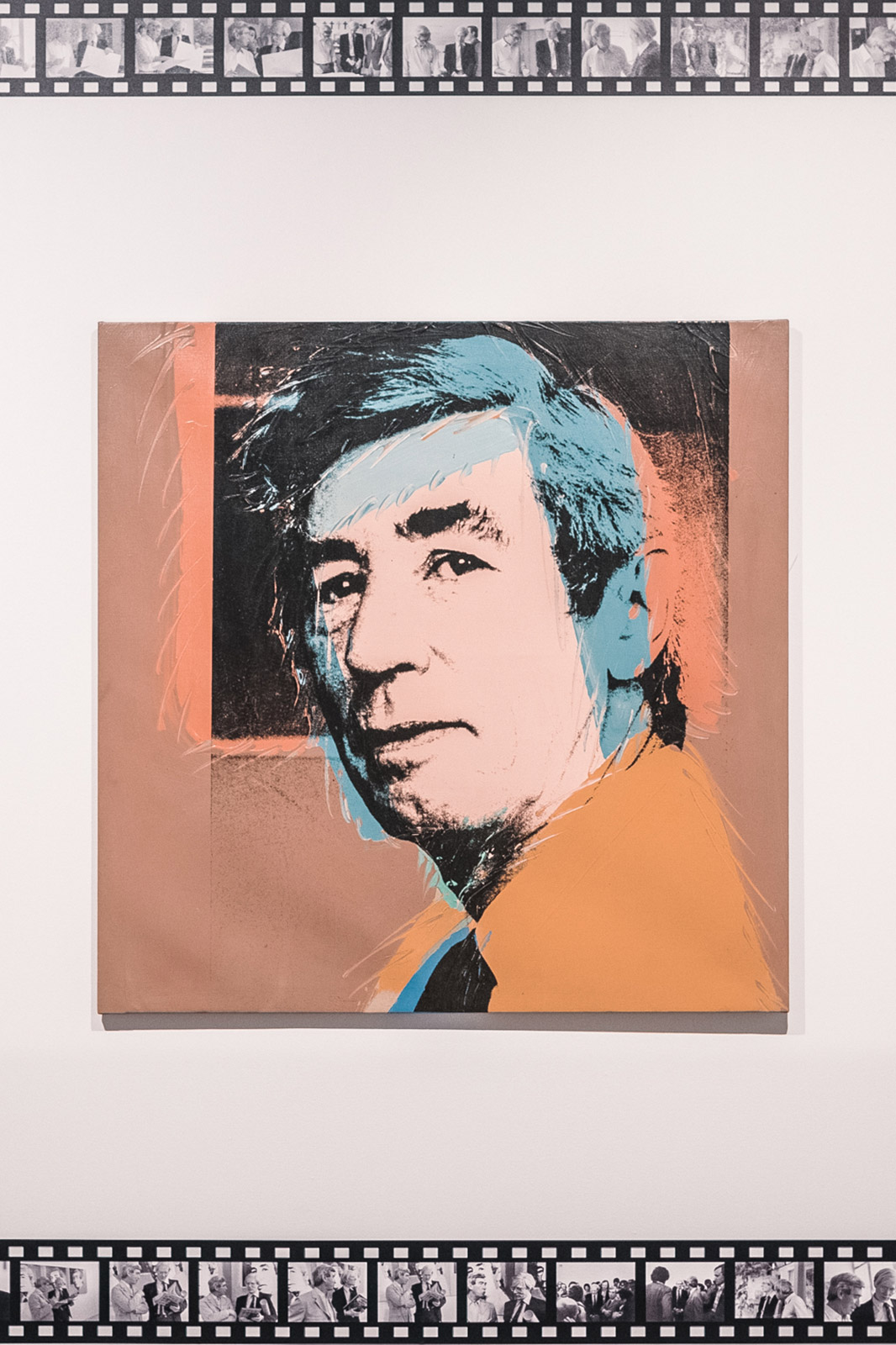

Portrait of Hergé, painted by Andy Warhol in 1977 © Pedro Pina

“H”, Plexiglass, from the Archibald Haddock Collection. Haddock brings a sculpted capital “H” to Marlinspike and says it’s a work of art © Pedro Pina

Assiduous in some contemporary art galleries in Brussels, Hergé created his own art collection © Pedro Pina The stories covered subjects as varied as pre-Columbian art, Van Gogh, Tutankhamun, Brueghel, Utrillo, Dürer, Goya, and Monet. Others introduced readers to museums such as the Cinquantenaire, the Musée des Beaux-Arts of Tournai, as well as exhibitions in Belgian galleries.

With the appearance of The Adventures of Tintin and through his network of friends and acquaintances, Hergé will gradually build an image catalogue, which he could use to incorporate references to art movements in his work. Following his initiation to modern art in the 1960s, Hergé discovered the joy of private collecting and surrounded himself with art— works that he fell in love with and hung on the walls of his home and at Studios Hergé.

-

-

Novelist of the image

In several interviews, Hergé explained that he had always loved telling stories, and that he came to enjoy illustrating them, too.

Having been weened on silent films, black and white films, and German Expressionism, and influenced by his readings as a child and teenager, Hergé quickly developed considerable skill in the art of découpage, from staging to presentation. Throughout his career as an author-cartoonist, Hergé continuously honed his skills, creating atmospheres, staging sets and environments, building narratives, beginning his stories, creating his gallery of characters, and more.

The back wall of this room is covered with dozens of albums of “The Adventures of Tintin”, published in almost 100 languages. © Pedro Pina

Hergé is a cinema admirer. King Kong, for example, may have inspired the gorilla figure of “The Black Island” © Pedro Pina He adopted and transfigured a series of procedures borrowed from novelists, as well as a few tricks specific to cinematographic language, to create his original oeuvre, a harmonious blend of words and images.

The ellipsis, the running gag, the MacGuffin, word play, shifts between tragic and comical situations, humor, and the psychology of his characters are just some of the things that put Hergé in a league of his own.

-

-

Tipping point

1940. German troops occupied Belgium. With newspapers Le Vingtième Siècle and Le Petit Vingtième shuttered, Hergé no longer had a newspaper where he could publish his drawings. Then Brussels’s daily Le Soir offered him a job to create a weekly supplement for kids. The Adventures of Tintin first began reappearing in the supplement Le Soir Jeunesse until July 1941, and later appeared as a daily comic directly in Le Soir.

Model of the “Astronomic Observatory” made by Alan Leonis for “The Shooting Star”, an album published in 1942 © Pedro Pina

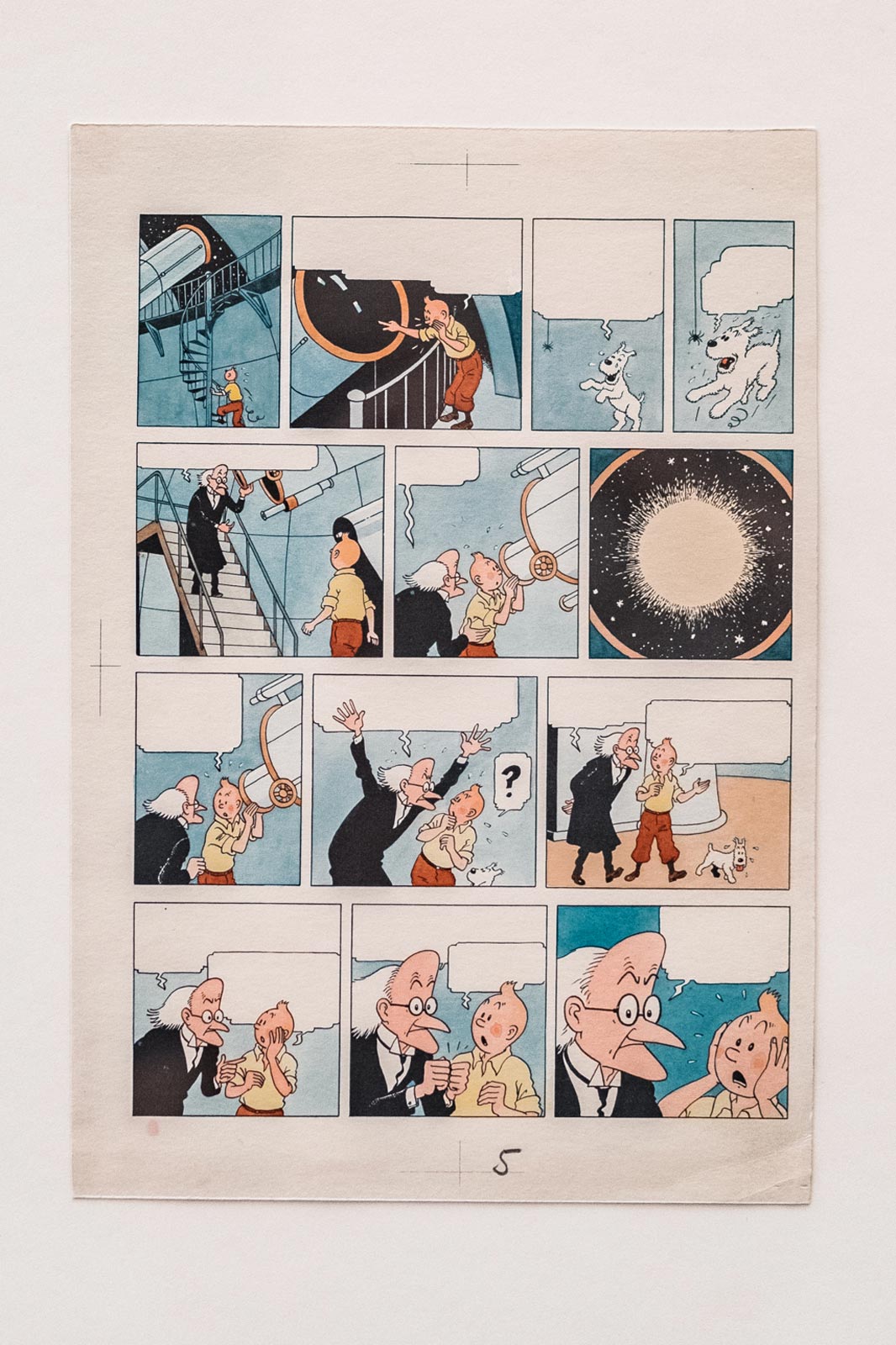

“The Shooting Star” is the first album published entirely in quadricoma © Pedro Pina

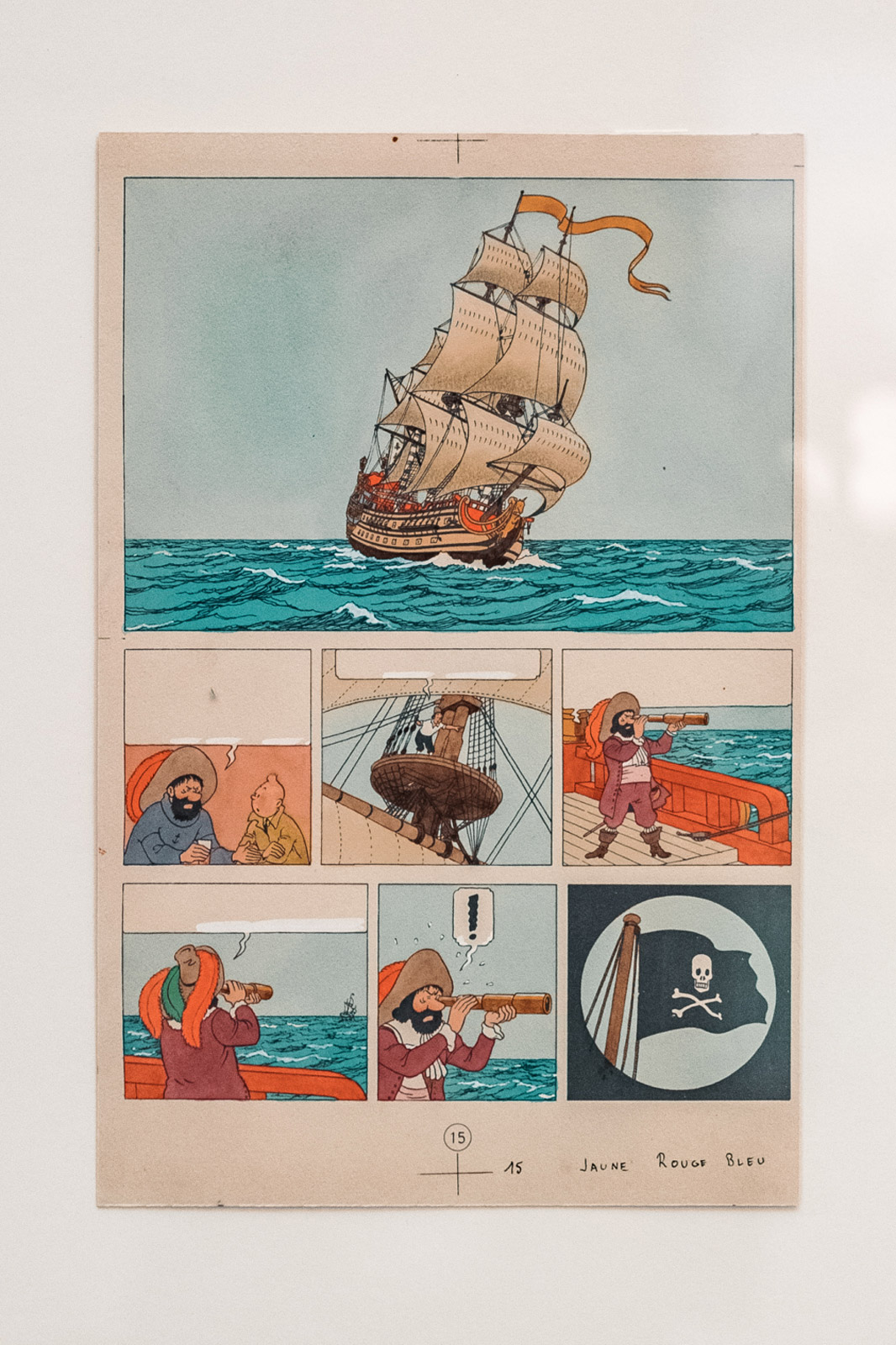

The story of “The Secret of the Unicorn”, adapted to the cinema in 2011 by Steven Spielberg, is continued in “Red Rackham’s Treasure” © Pedro Pina Hergé’s collaboration with Le Soir and certain Flemish papers—all mouthpieces of the occupying forces—was a real cause for concern after liberation. He was arrested and brought in for questioning several times in September 1944, and was not officially cleared until May 1946 when he received his certificate of good citizenship.

The Second World War marked a period of success for the cartoonist, and Casterman printed his albums in record numbers! But more importantly, this was when he reached maturity as a graphic artist. Spurred on by his publisher, but still guided by his principles of simplicity and readability, Hergé finally embraced color in The Shooting Star. He opted for delicate, flat tones without shadows or gradations. Faced with the daunting task of adding color to his older black and white albums, he knew he would need help. And that’s when he met Edgar P. Jacobs.

This period also marked the emergence of a new character, Captain Haddock, who made his début in The Crab with the Golden Claws. This great sentimental character, with his gruff demeanor, generous heart, quick temper, and panache for hurling insults, never ceased to amaze with his unfailing sense of friendship.

-

-

A paper family

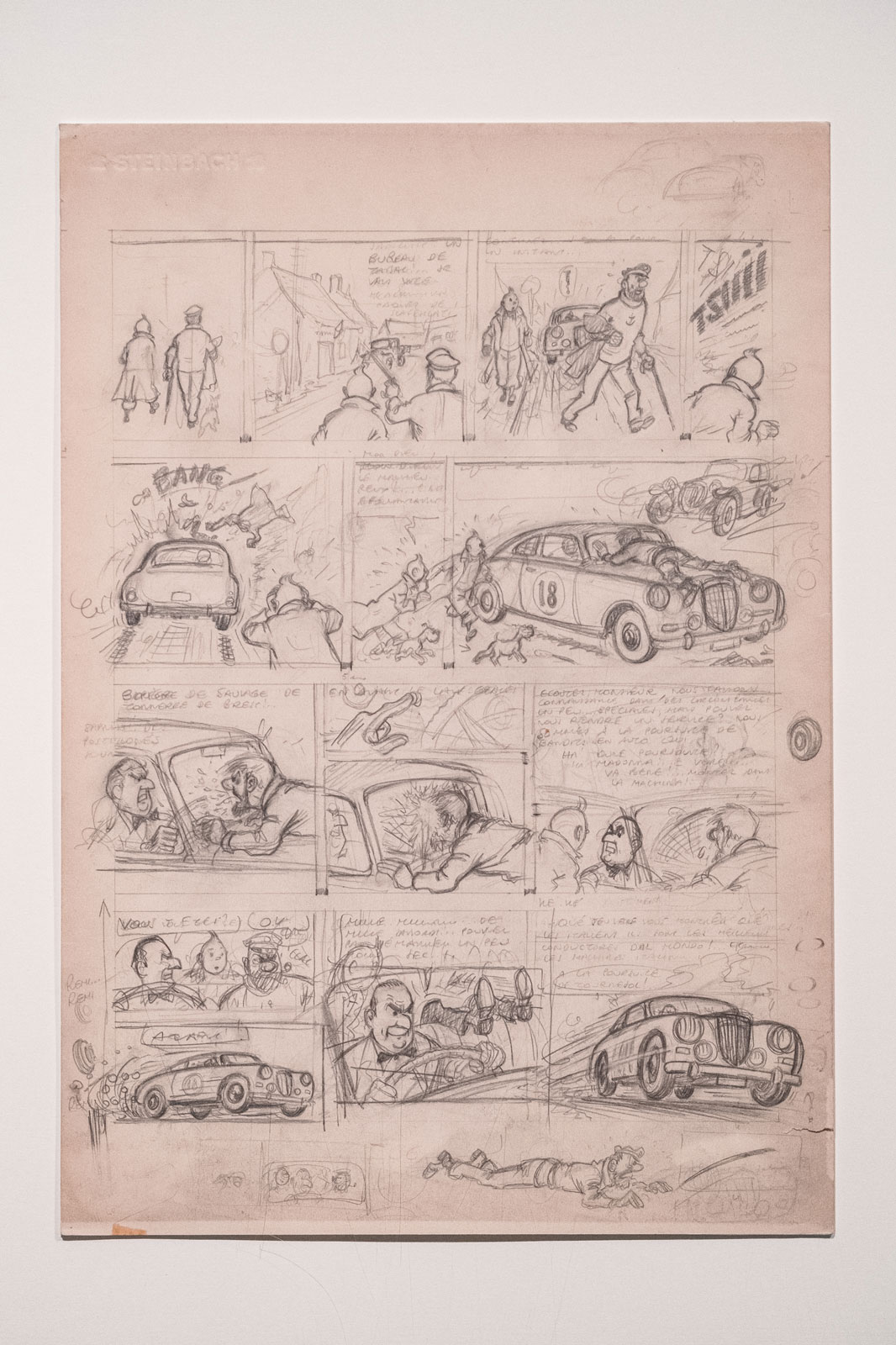

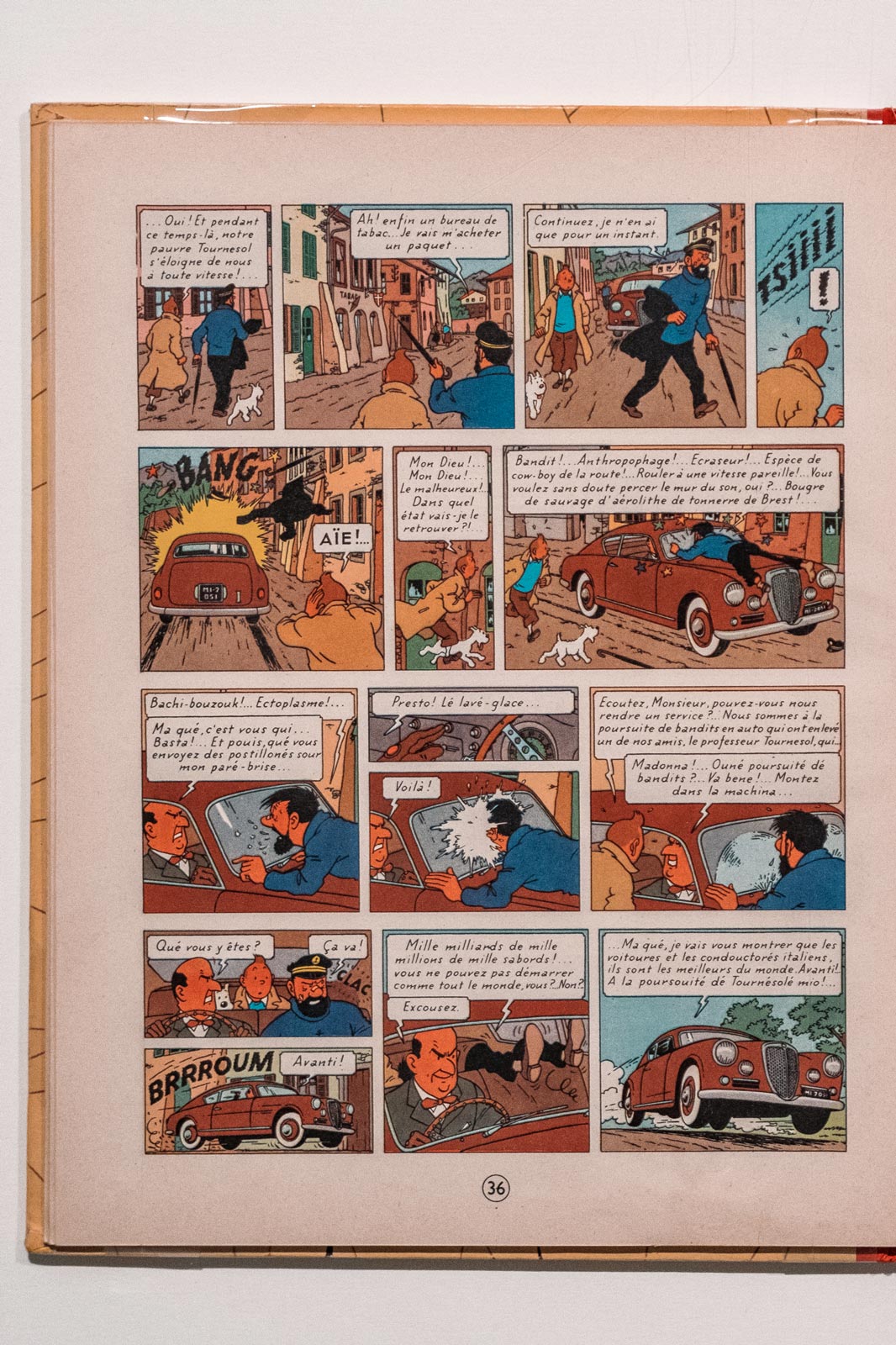

The pencil-drawn boards presented in this room attest to Hergé’s great mastery of portrait art.

His pencil strokes were like magic when he focused on his characters. Up close or at a distance, every drawing is proof of just how good Hergé was at his craft. His sensitivity, feeling, and expertise were remarkable. He observed his subjects and often had people pose for him, capturing them in drawings to masterful effect.

Marlinspike is a copy of the Chateau de Cheverny, in the Loire Valley, from which the side wings have been removed © Pedro Pina

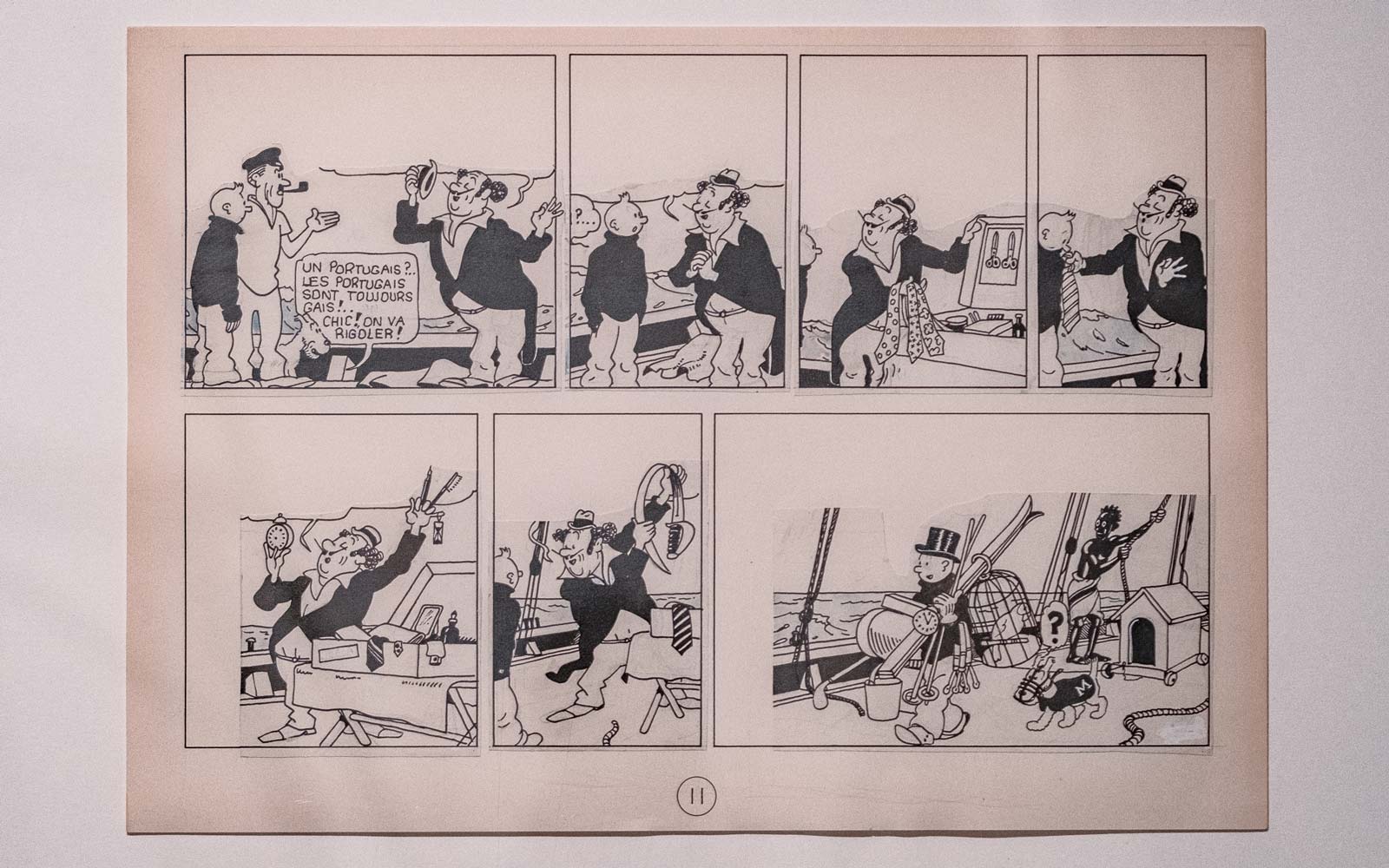

The Portuguese character Oliveira da Figueira appears in the 4th álbum, “Cigars of the Pharaon” © Pedro Pina

In the model of Marlinspike you can find some of the main characters of “The Adventures of Tintin” © Pedro Pina

Pencil sketch of board 36 of “The Calculus Affair”, 1955 © Pedro Pina

Page 36 of the 1st edition of “The Calculus Affair”, 1956 © Pedro Pina Although comics have long been regarded as a minor art, figures like Hergé have propelled them to unrivalled artistic heights. Certain lead pencil sketches of Captain Haddock, Tintin, or Professor Calculus, for instance, are exercises in style with enough complexity, astute turbulence, and accuracy of tone to rival works by such masters as Dürer, Holbein, Da Vinci, Ingres, and others.

-

-

Coeurs Vaillants Magazine

Hergé had an intimate relationship with the characters he created… or at least with some of them. This was certainly the case with The Adventures of Tintin, although he was less close to his characters Quick and Flupke despite the fact that the two Brussels street urchins spend their whole time playing pranks and games based on the author’s own childhood experiences. On the other hand, Hergé was not at all attached to the characters from Jo, Zette and Jocko.

Jo and Zette (here without Jocko), characters created by Hergé for the French magazine “Coeurs Vaillants”, run from Karamako’s eruption © Pedro Pina

Nestor, from “The Tintin Adventures”, will also be drawn unbalanced on skates, as this character of “Adventures of Jo, Zette and Jocko – Mr Pump’s Legacy” © Pedro Pina This series was commissioned from Hergé and was not something he created through his own inspiration. He worked on the series without enthusiasm; the number of stories can be counted on one hand.

The author was excited to see his work being published in France, Switzerland and Portugal but was less pleased with the slapdash way in which pages of Tintin, as well as Jo, Zette and Jocko, were printed in Coeurs Vaillants without much respect for the original colour schemes and nowhere near the quality of the books produced by Casterman.

-

-

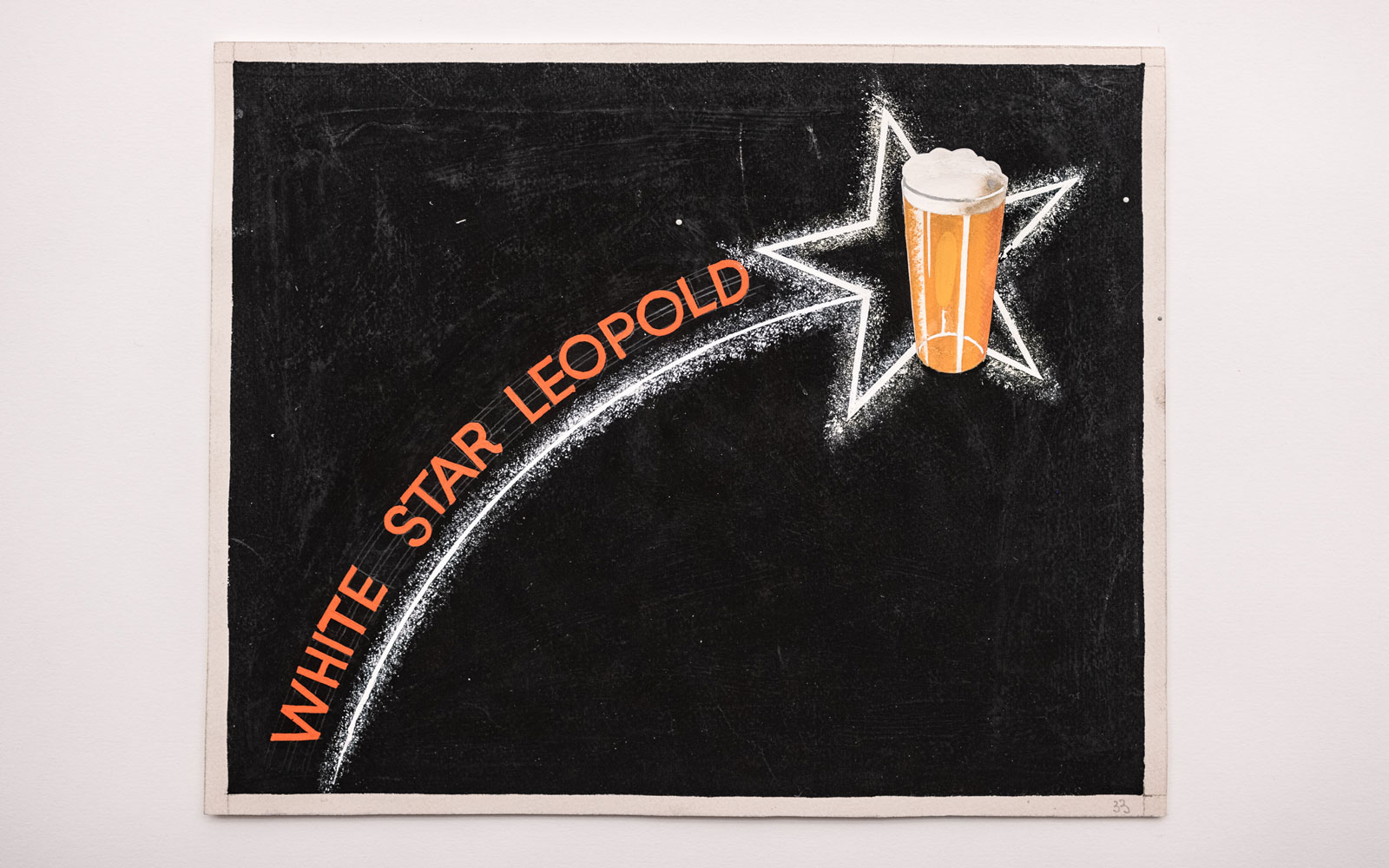

The art of advertising

The thirties marked the launch of Atelier Hergé-Publicité. This room sheds light on a lesser-known aspect of the cartoonist’s talents: big, beautiful posters designed by Hergé and his then partner, José De Launoit. They show the true advertising and promotional talents of the father of Tintin.

The documents on display offer a lesson in graphic design, from simplicity of message to lettering, distribution, spacing, and color—characteristics and choices that make up the fundamental principles of the clear line drawing style.

In the 1930s, Hergé discovers the art of advertisement, creating images and posters for big Belgian companies © Pedro Pina

Advertising project for the Belgian beer White Star Leopold, in the beginning of 1930s © Pedro Pina The same principles apply to illustrations in cover art, advertising brochures, and other ad-related documents.

This lesser-known phase in the artist’s career also includes an equally unknown promotional cartoon serial, Tim l’écureuil, which was influenced by the vision of Disney Studios at the time.

-

-

Lesson from the East

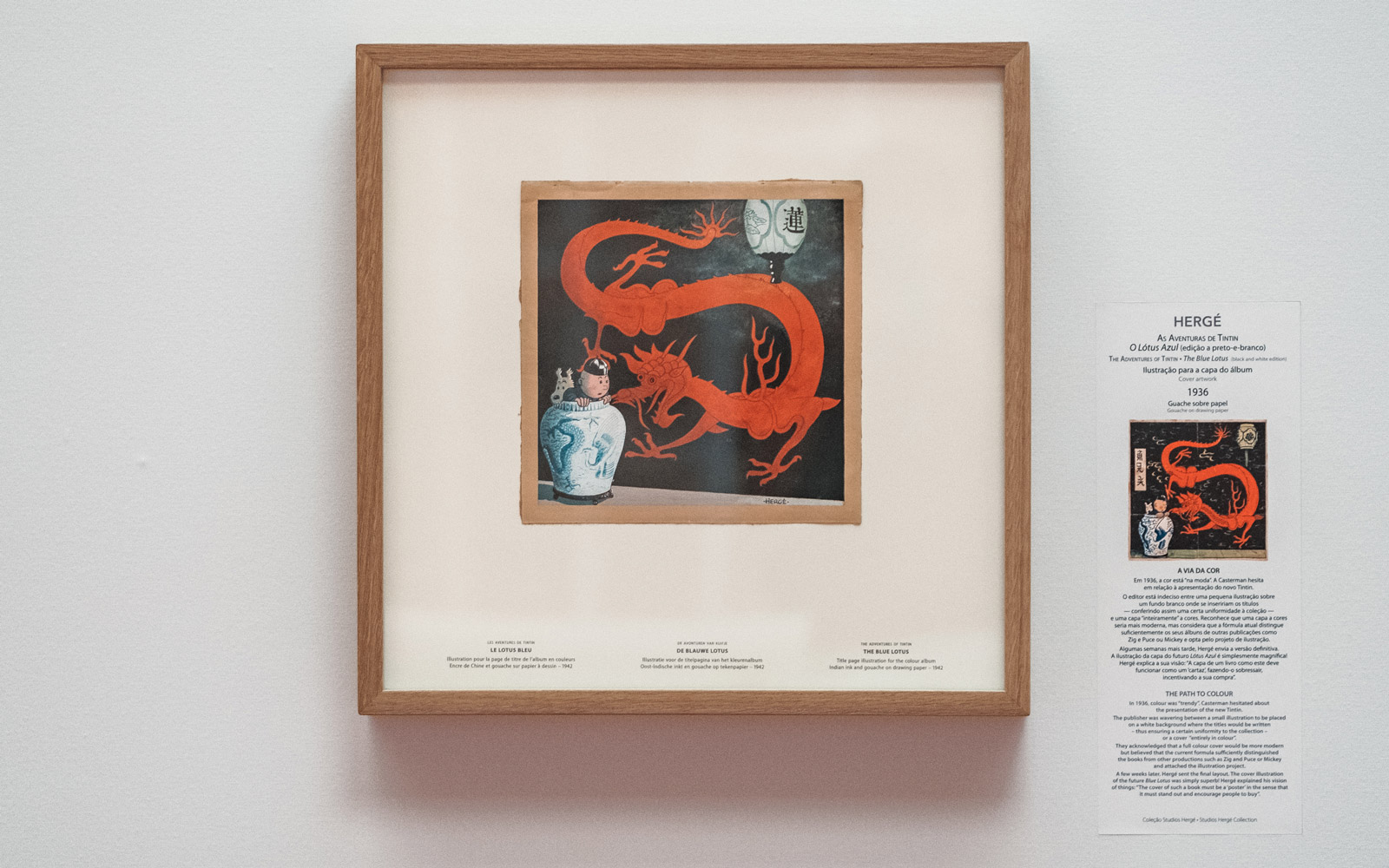

Undeniably, the highlight of the thirties for Hergé was his meeting with Chang Chong-chen and the release of The Blue Lotus.

A young Western artist “encountered” a young artist from the Far East. They shared common interests: art (painting, sculpture, drawing, comics), religion (Chang was Catholic), language (Chang spoke French). The result: two worlds came together!

Hergé started his career in January of 1929, in the “Petit Vingtième”, a the supplement of the Belgian newspaper “Vingtième Siècle” © Pedro Pina

With “The Blue Lotus”, Hergé discovers a totally new civilization and becomes aware of his responsibility as an illustrator © Pedro Pina

Tchang Tchong-Jen helps Hergé to become more openminded and rigorous about other cultures © Pedro Pina

Chinese brush set offered to Hergé by Tchang Tchong-Jen © Pedro Pina The meeting sparked a new Tintin adventure that took a new narrative approach that was markedly different from previous albums.

This room celebrates this event through a number of pieces: boards with India ink, Le Petit Vingtième cover illustrations in connection with The Blue Lotus, leaflets, some of Chang’s personal objects, and more.

The wall of Le Petit Vingtième leaflets illustrates how busy Hergé was as a cartoonist and illustrator in the thirties. Creating The Blue Lotus obviously wasn’t the only thing that kept him busy. You’ll notice the nod to Quick and Flupke and other Hergé productions from this prolific period of work.

-

-

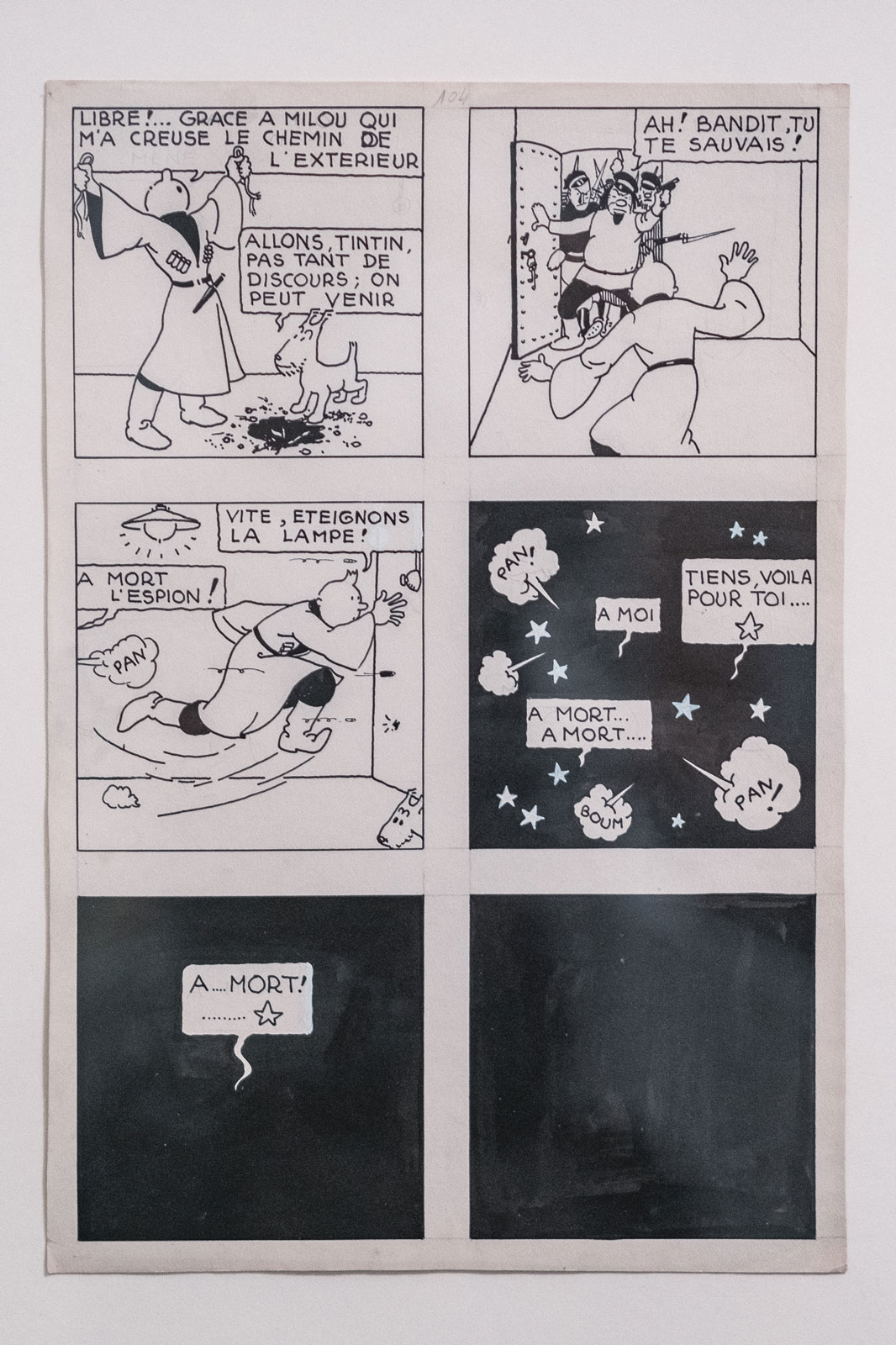

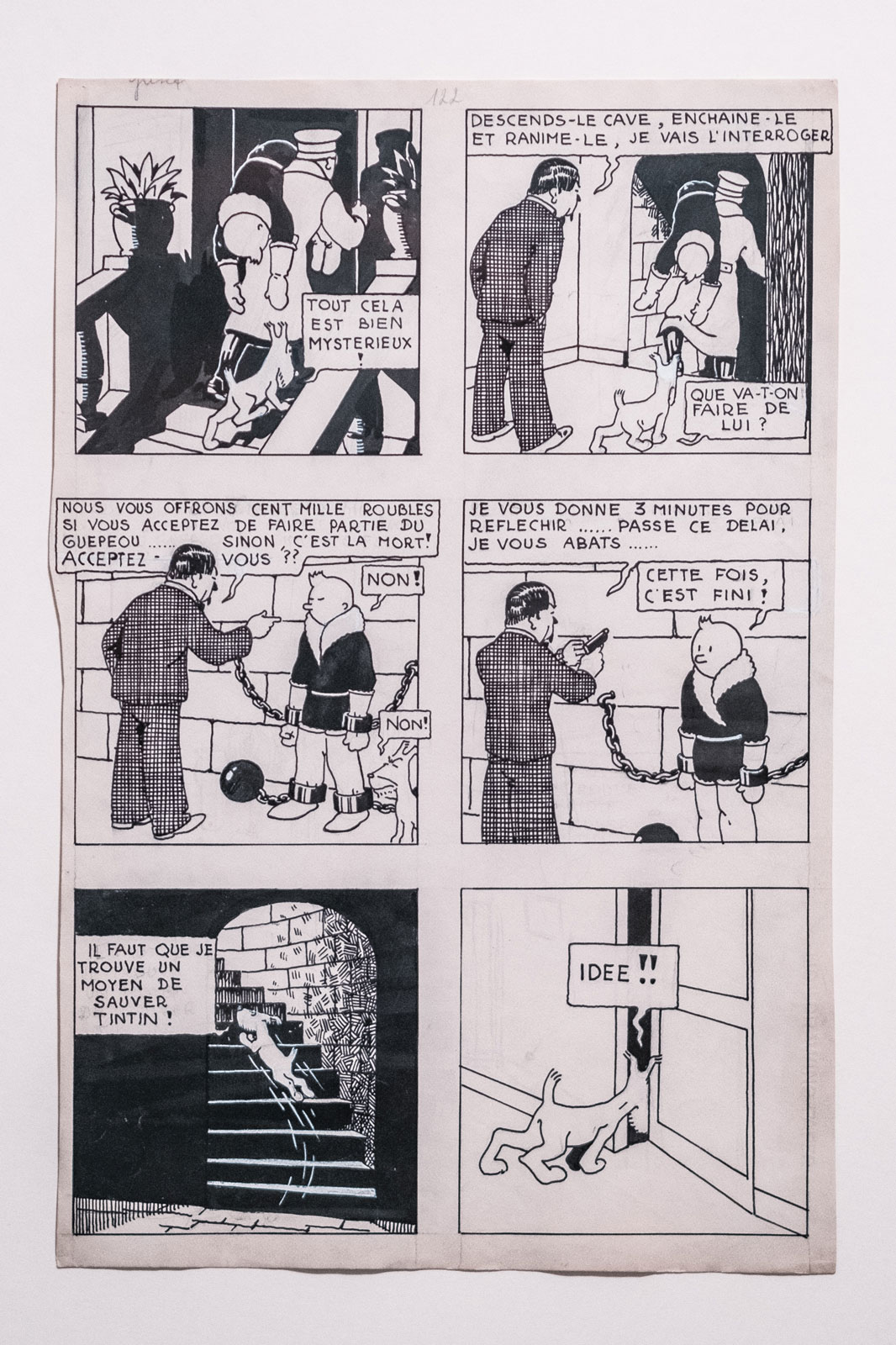

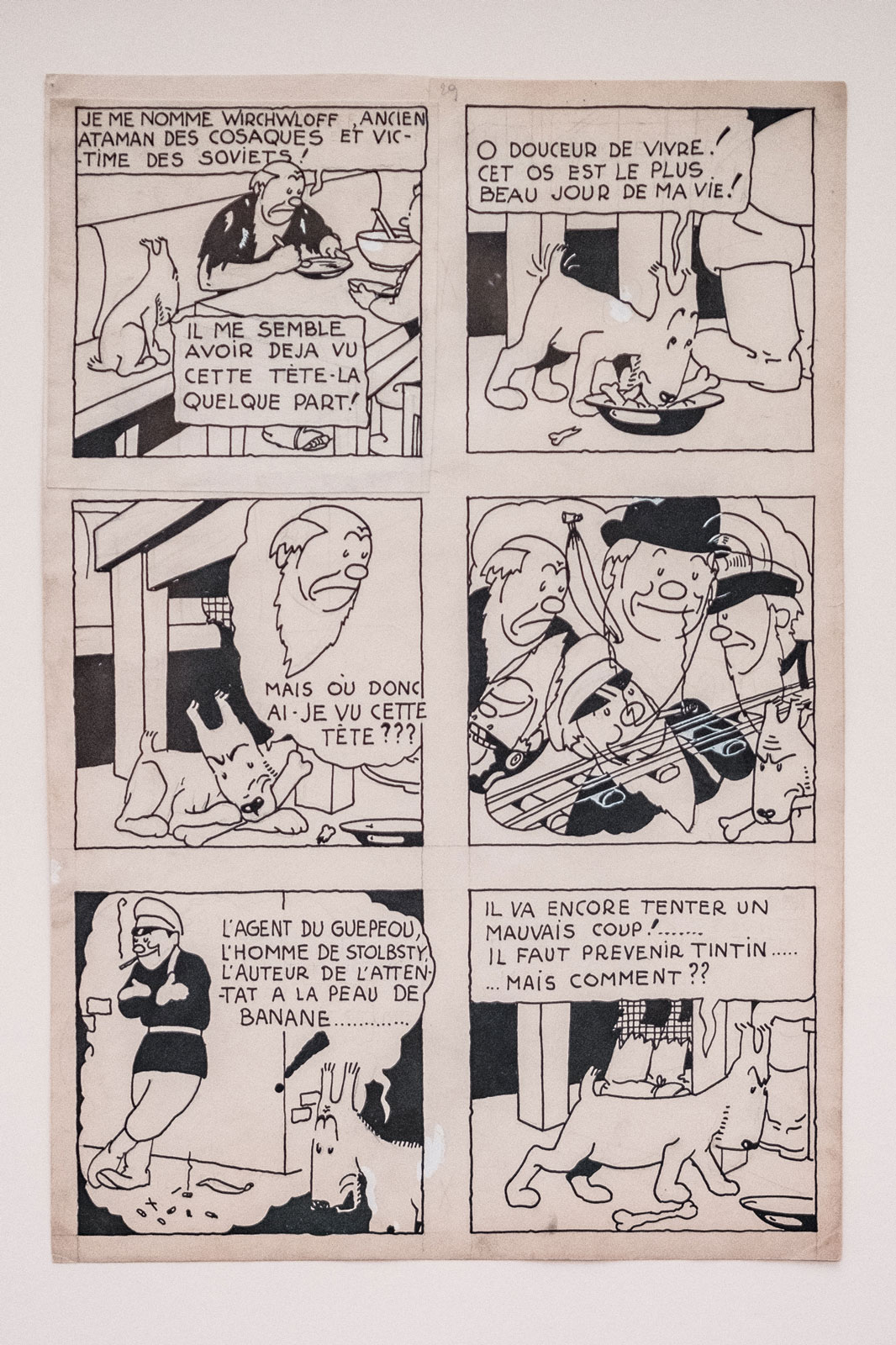

The birth of a myth

Hergé’s destiny forever changed on January 10, 1929. Tintin was in motion! Hergé had always loved telling stories. With his spongelike mind and boundless curiosity, the self-taught artist quickly learned the art of narrative, découpage, and other tools of the trade.

Tintin seems to die “In the Land of the Soviets” – on the contrary, it was the beginning of a great career © Pedro Pina

At first, stories were built as they were published, week after week © Pedro Pina

Snowy, Tintin’s white fox terrier, is a faithful companion since January 1929 © Pedro Pina Join us as we discover the creative transformation that led young Georges Remi to become Hergé, father of European comics—from his self-proclaimed early influences (Rabier, Saint-Ogan, MacManus) to his first significant drawings, from childhood doodles to refined boards, from approximate reproduction techniques to beautiful prints on superior quality paper, and from prepublication in Le Boy-Scout to his Casterman albums.

We will also take a closer look at some remarkable strips from Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, which are a beautiful reflection on “the silent beauty of black and white” and serve as a primer on the clear line style.

-

Co-production

Sponsor

Sponsor Hotel

Media

The Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation reserves the right to collect and keep records of images, sounds and voice for the diffusion and preservation of the memory of its cultural and artistic activity. For further information, please contact us through the Information Request form.