Donation of works by Espiga Pinto

«Feet on the ground, head in the cosmos» – this is how José Manuel Espiga Pinto (1940-2014) defined his work. CAM recently received a donation of drawings, study notebooks, sculptures, engravings, and a catalogue book by him, produced between the 1960s and the 1980s.[1]

Born in Vila Viçosa, Espiga Pinto attended the Lisbon School of Fine Arts between 1957 and 1960 and held his first solo exhibition in 1958 at the Galeria Pórtico. In 1960 he returned to the Alentejo to teach at the Industrial and Commercial School of Estremoz, where he remained until 1966. Between 1979 and 1989 he also taught at IADE in Lisbon.

The fact that he was born in the Alentejo was decisive in this early phase of his production, characterised by David Santos as a «late neo-realism.»[2] In the artist’s own words, he decided to «Sing the Alentejo», revisiting «the fields, the work, the peasants and horses, in a symbiosis between the harshness of working from sun up to sun down and the experience of the traditional clothing, fairs, olive oil presses, popular festivals, religious-pagan festivals, and festivals at the end of the olive harvest…»[3]

It was only later that this field of references intersected with a tendency towards abstraction, at which point we see a growing importance for geometry in defining the structure of works, which aspire to a symbolic representation of broader cosmographies.

Although this characterisation of his production is generally correct, this donation allows it to be problematised. The works dating from the 1960s mostly present themes from the rural world of the Alentejo with neo-realist affinities. Yet not only does their formal expression vary, but we can indeed already detect the presence of abstraction.

Works such as Untitled, 1960 (inv. 20DP4647), or Untitled, 1966 (inv. 20DP4648), explore the theme of the peasant girl with a plastic expression that is very close to some of the more conventional Portuguese modernism.

Works such as Picadeiro, 1963 20GP2846), Untitled, 1962 (inv. 20GP2845), Untitled, 1963 (inv. 20GP2847), and Brincando com o ‘Cavalo de Tróia,’ 1963 (inv. 20DP4667) allude to the same rural themes, but in a language very much of Espiga Pinto’s own: the use of a single colour, the definition of shapes formed by patches interspersed with the emptiness of the background, a certain jocularity or irony in the characterisation of characters and situations, the enhanced expressiveness of the background – either by what it contributes to the definition of form, or by the breathing space it gives to the overall composition.

A jovial perspective of figurative situations and the use of expressive patches in parallel with empty backgrounds are particular characteristics of Espiga Pinto’s work from this period. This authorial imprint becomes very evident in an album of photographs of drawings and paintings that he sent to the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in 1965 as a report on the grant he received from the Foundation over three months.

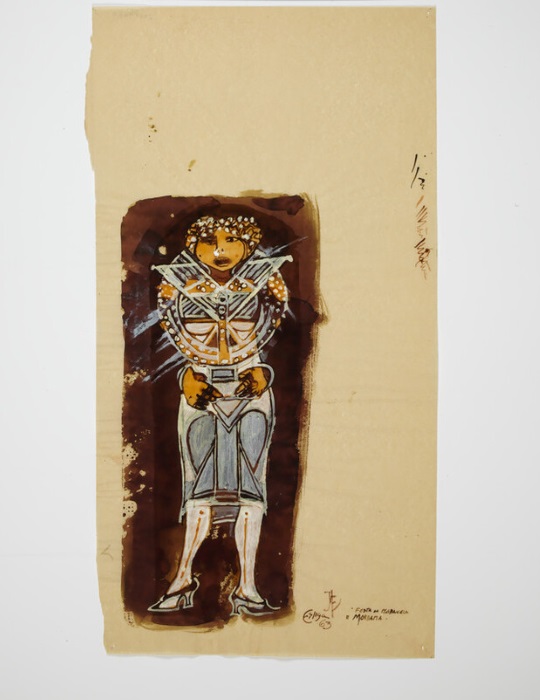

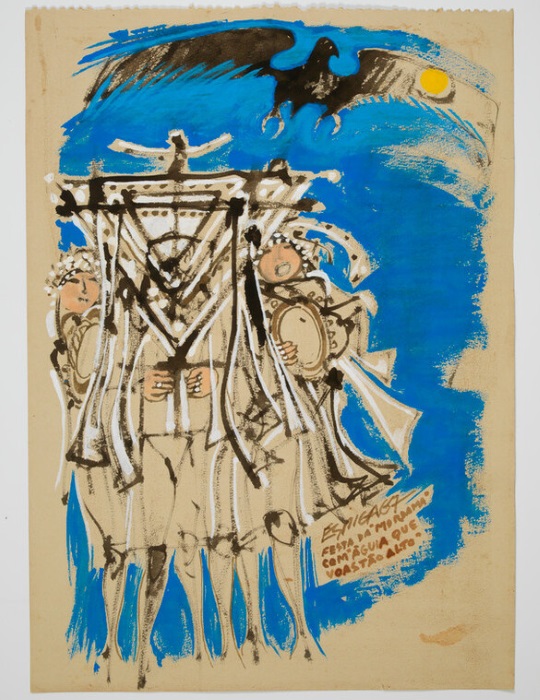

Yet the geometrical structuring of compositions (which became increasingly evident in the following decade) began to creep in during the 1960s: in this donation, the same rural themes of animals and festivities appear in more geometric and tendentially symmetrical compositions, with more static and hieratic figures, in which the artist was already experimenting with a controlled use of colour. Examples include Festa Mordama, 1962 (inv. 20DP4649), Festa da Madanela e Mordama, 1963 (inv. 20DP4650), Festa Mordama, 1963 (inv. 20DP4651), and Festa da ‘Mordama’ com ‘Águia que Voas Tão Alto,’ 1967 (inv. 20DP4662).

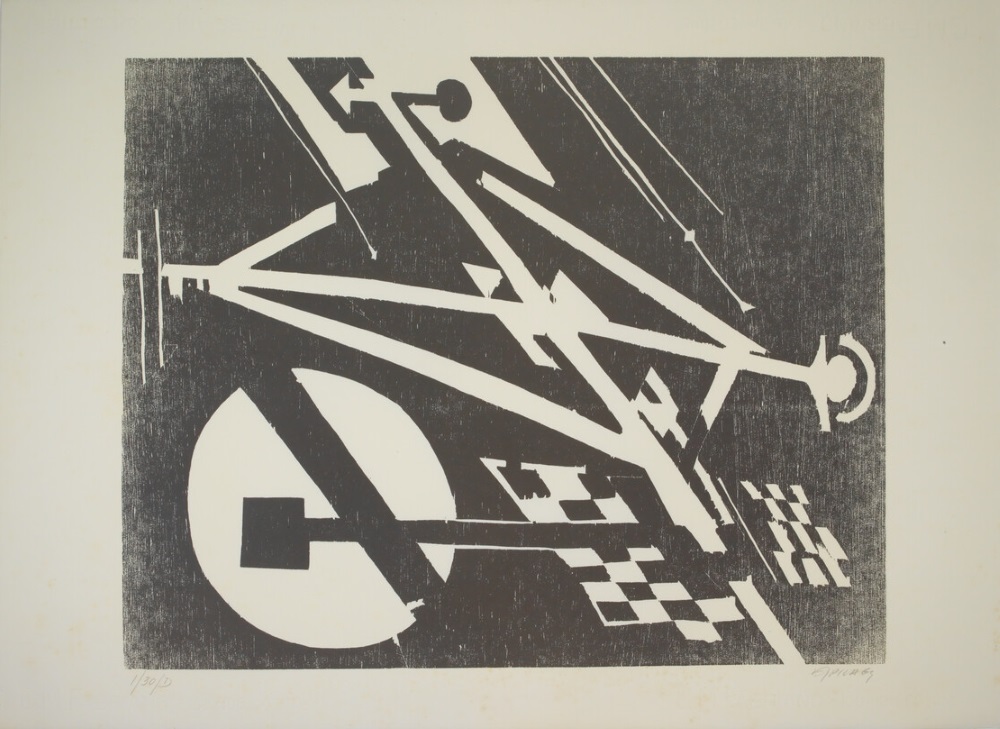

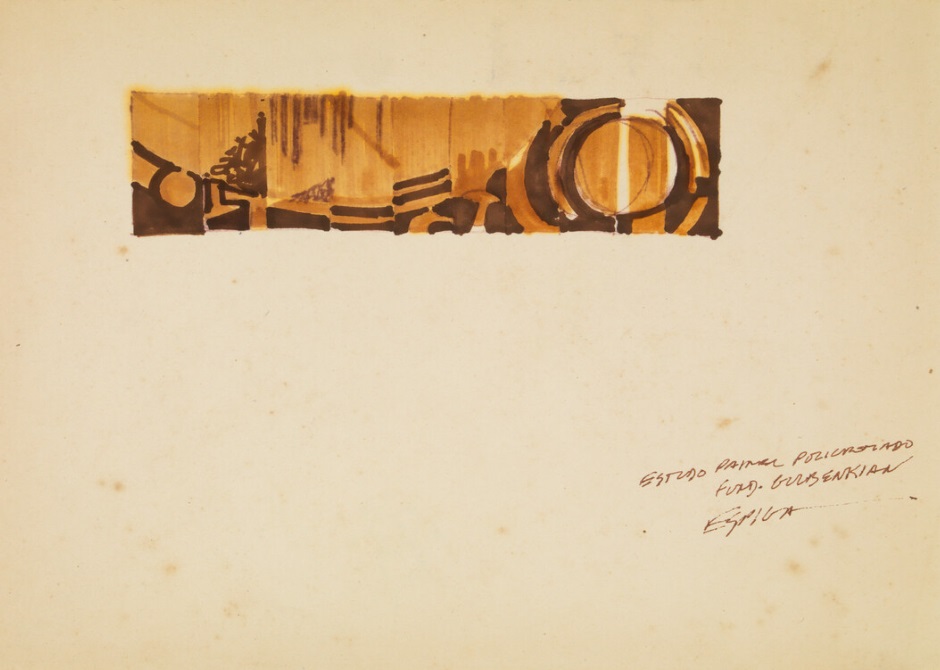

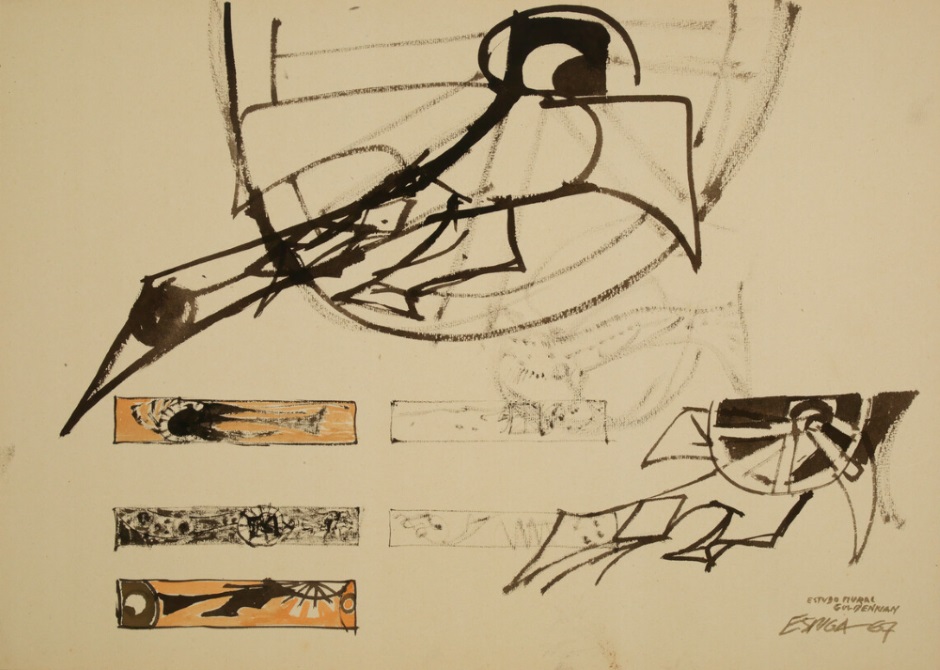

In reality, Espiga Pinto’s initial experimentation with abstraction took place alongside his practice of figuration. Still in the 1960s, he not only produced geometric abstractionist screenprints (Untitled, 1965, inv. 20GP2843; Untitled, 1965, inv. 20GP2844) but also produced a large abstract panel to decorate the headquarters of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, of which we can see some studies from 1967 in this donation (which add up to a model of it already held in the CAM Collection). This panel would seem to herald his aspirations for his production in the following decade.

Although it is tempting to categorise Espiga Pinto’s early work as late neo-realism due to its subject matter, we might dare to say that the artist was actually experimenting with several languages simultaneously, crossing figuration – in itself a diverse field – and abstraction. Indeed, if the peasant theme brings him closer to neo-realism, his plastic expression distances him from it. This doesn’t mean that the language of what we can historically call neo-realism was necessarily uniform, but it does tend to possess a pervading need to denounce injustice and inequality, which often translates into a certain seriousness or anguish. In Espiga’s rural-themed works, however, there is an irony and jocularity that departs from this emotional spectrum. The artist represents the rural world that is familiar to him, especially in its most joyful and festive expressions, with humour and irony.

The production of this decade can thus raise two types of interconnected questions: if we try to dispense with the epithet ‘late’ that so often accompanies evaluations of peripheral art histories (thus reflecting their inferiority complex vis-à-vis the central historiographical canons and passive acceptance of the rhythm imposed by them), what historical significance can this production still claim? In a decade in which national and international art was already definitively following other formulations (from pop art to nouveau réalisme, post-painterly abstraction, conceptualism or op art), what relevance can this production by Espiga Pinto have? Is it possible to recognise a resistance, in line with emerging countercultures, to development centred on urban growth and a logic of capitalist production? An apology for a type of community and social cohesion as opposed to the growing atomisation and individualism of urban societies? Praise for a return to rurality, in line with emerging ecological awareness, as an alternative to technological and scientific progress that had already revealed its potential for catastrophe? A resistance to the idealised image of rural people created by Estado Novo propaganda?

Espiga Pinto’s experimentation with languages and media continued through the 1970s. Geometry and abstraction effectively took on another dimension in his work, but it was a new reflection on space and the symbolic potential of art in public space that especially occupied the artist.

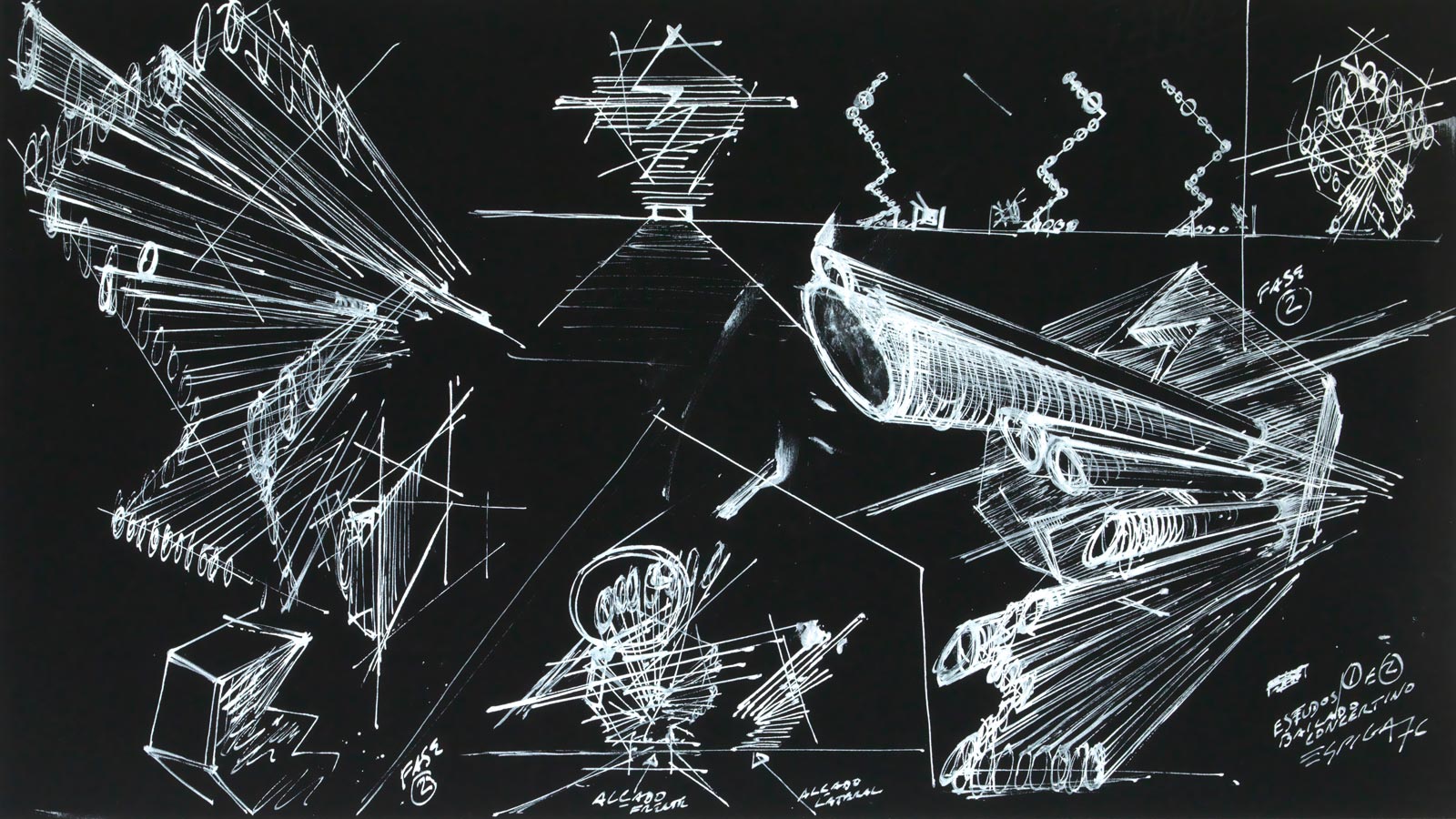

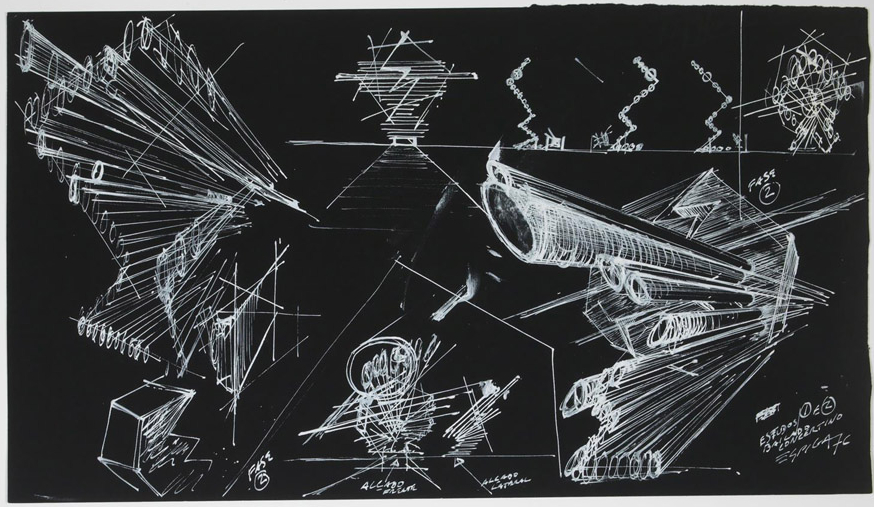

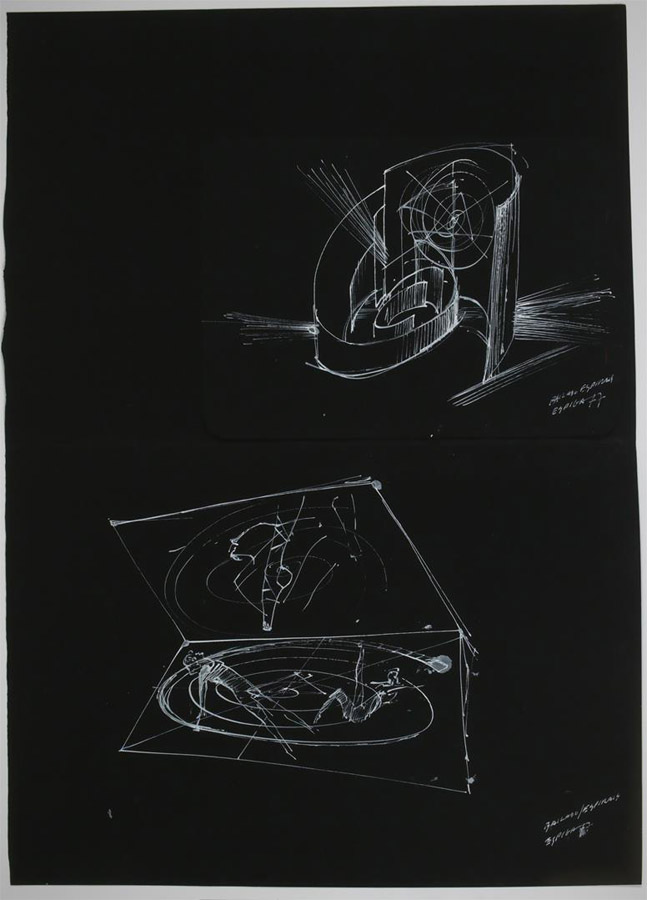

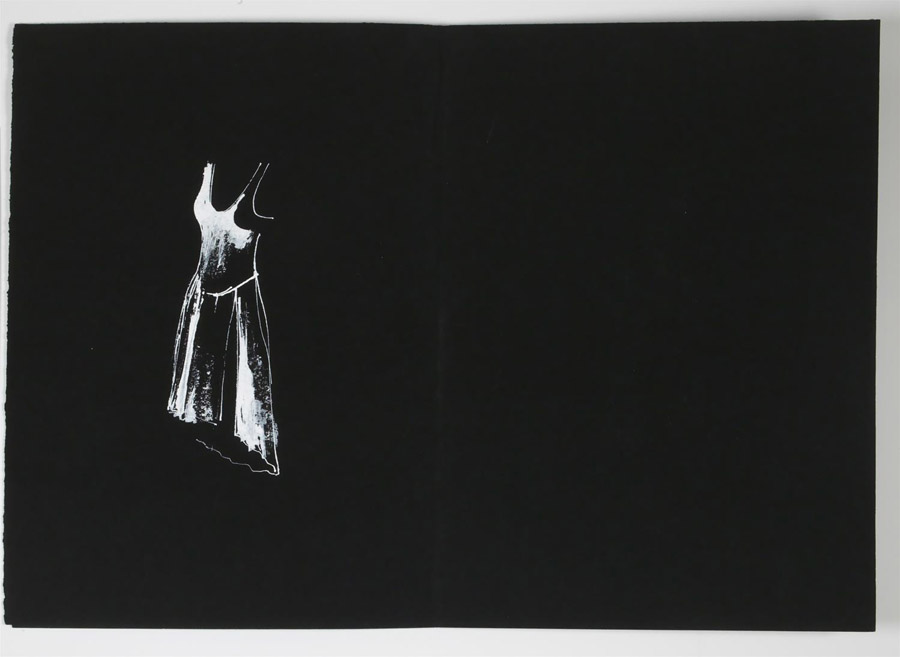

These were prolific years for the creation of sets and costumes for the Ballet Gulbenkian , of which we find some studies among the works in this donation.[4] Usually produced in white gouache on black card, there are studies for Bailado Concertino, from 1976, for Enigmas de Édipo, from 1977, Bailado Espirais, from the same year, as well as a study for a costume for the ballet Da vida e da morte de uma mulher só, realised in 1982. Here, too, we can notice the abstract tendency of the set designs, with the curved, spherical and spiral planes and shapes that can be found in subsequent creations.

His activity in the field of set design – which he also developed for the Teatro Experimental de Cascais between 1969 and 1971 – was recognised in 1970 with the Press Prize for the sets for the Ballet Gulbenkian , and in 1973 with the São Paulo Biennial Prize for the sets and costumes for the ballet Dulcinea, by the same company.

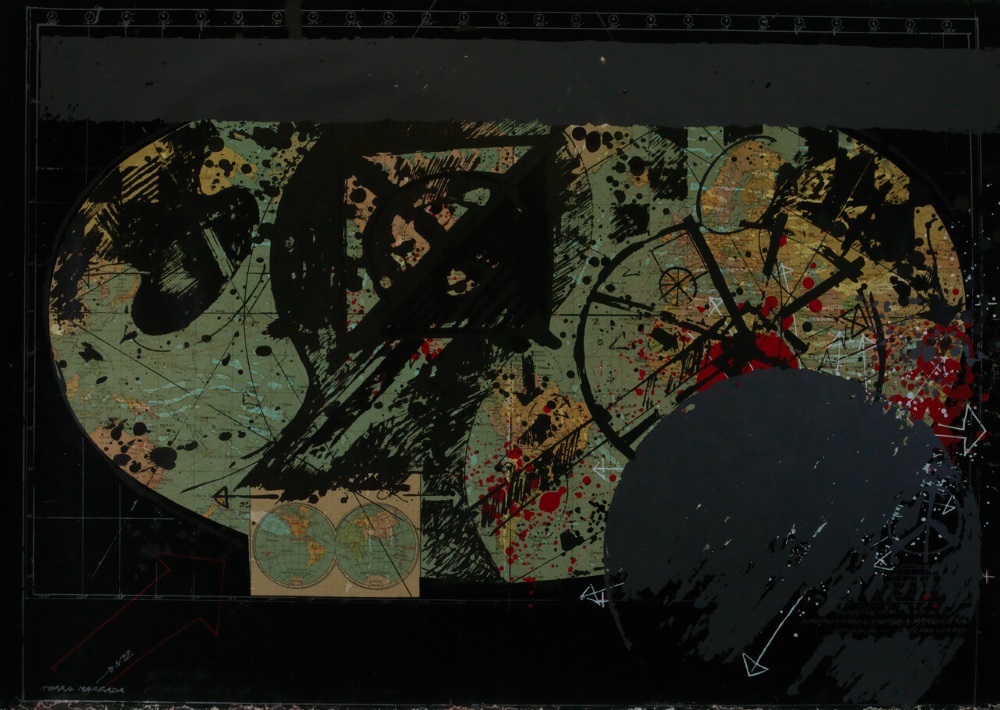

This plastic reflection on space would expand to other areas of Espiga Pinto’s production throughout the 1970s. In screenprints such as Terra Marcada N.º 2, from 1972, he set out a cosmographic representation of the world in a geometric, abstract and symbolic language.

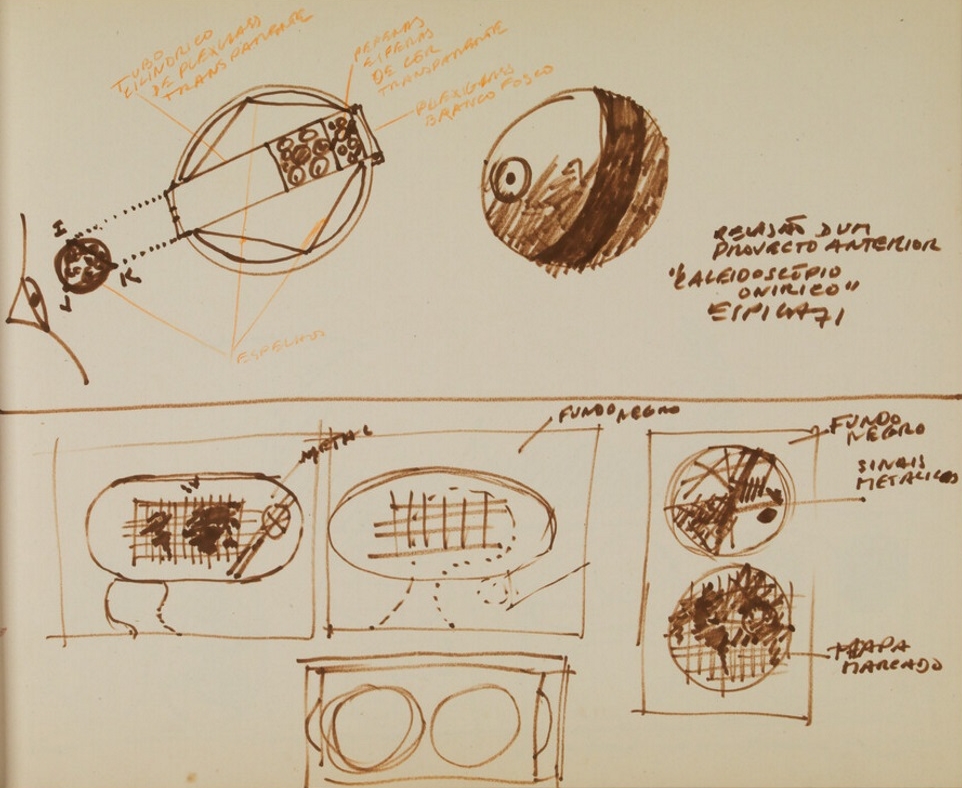

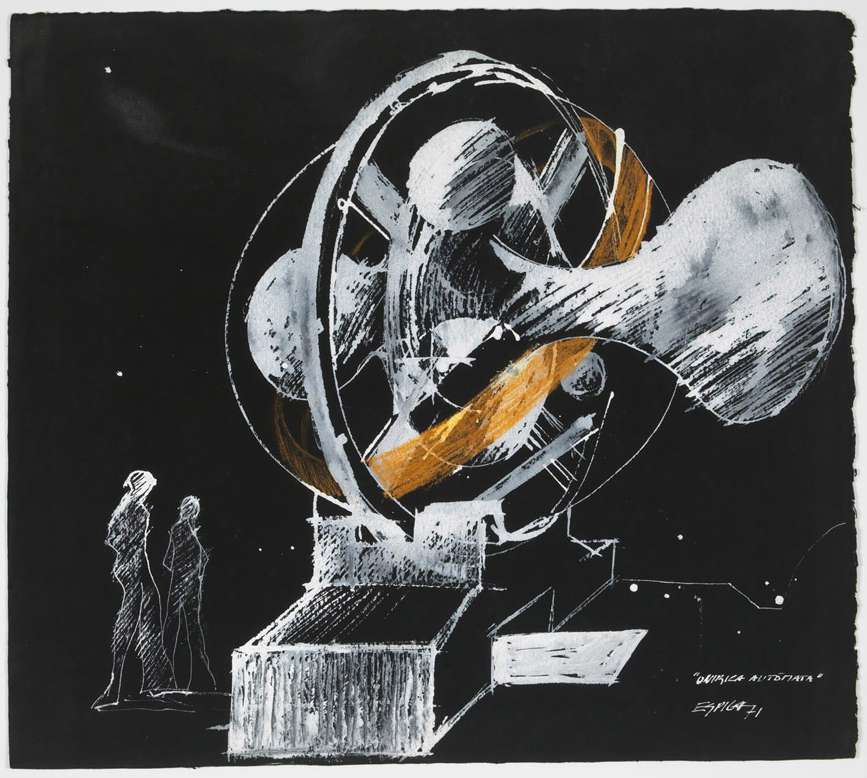

It may be that the creation of sets led to the expansion of two-dimensional drawings, paintings and engravings to a three-dimensional and performative occupation of space. In a notebook of studies made between 1971 and 1977, we find designs for what appear to be devices for cosmic artistic-poetic communication. In the notes accompanying these drawings, we read «oneiric kaleidoscope», «oneiric ear» with «sound-sensitive cells», and realise that Espiga Pinto imagined their realisation in materials such as plexiglass, bronze, copper, light bulbs, ropes, polyester, wood, mirror, metal bearings, and small coloured spheres.

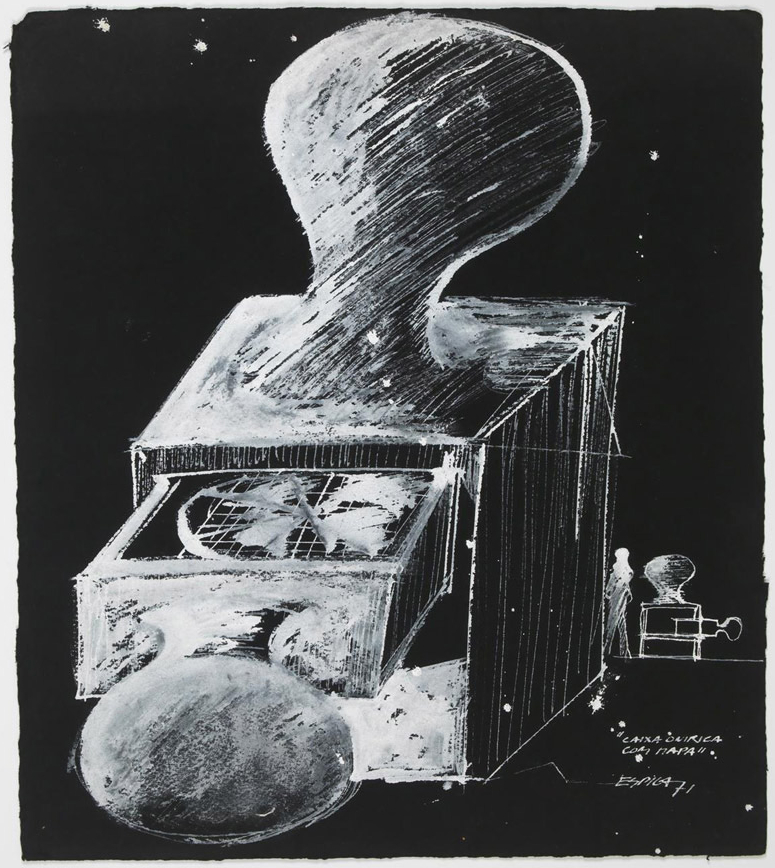

Although the artist dismisses these sketches on one page as a ‘project that is definitely useless,’ they nevertheless seem to be machines for dreaming up another type of communication (similar to the «cosmolanguage» that Costa Pinheiro invented around the same time) and were probably sketches necessary to conceive drawings for other purposes, which also form part of this donation. In this set of drawings there are representations of oneiric devices with affinities to the world of science fiction. Made in 1971, they feature white gouache on black card and have titles such as Lanterna Onírica, Caixa Onírica com Mapa, Onírica Dupla, Onírica 2ES-1BO-PEN-1/2RO, and Onírica Autómata. Some of these drawings were to be realised three-dimensionally (thus being studies for sculptures, urban intervention projects, and performances), as we can see in some photos of exhibitions published on the author’s blog (Lanterna Onírica appears with some recurrence) and in audiovisual recordings of the artist’s installations and performances.

In 1973-1974, Espiga Pinto received a scholarship from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation to continue his research into interventions in urban space in Sweden and France. The focus of his research into cosmic-symbolic, performative and urban space can be seen in the book that we find in this donation (and of which the Gulbenkian Archives hold three more copies). It is a catalogue of an exhibition by the artist held in 1973 at Galeria Alvarez (Porto) and at Galeria Quadrante (Lisbon), in which we find a summary of the lexicon of his plastic language at the time. In this catalogue-book with a circular format, we repeatedly see the motif of the hand (the ‘hand that creates and destroys,’ he says in a short fiction he created for RTP in 1977),[5] as well as some of his sculptures, paintings and drawings in which the sphere and the circle are recurring forms; we see some of the murals he created for public spaces – namely the mural created for the FCG headquarters – where the motif of the circle and abstract forms is also a constant; there are photographs of set designs reminiscent of science fiction and various views of exhibitions he had held; we see his «oneiric lantern» realised three-dimensionally, accompanied by the inscription «From the brain to being to living the cosmic scene», we see his sculptures arranged in space and «activated by children», in a record of the 1972 Egotemponírico performance-installation, as well as photographs of a performance in an urban space, in which a man and a woman pull a rope in opposite directions.

Despite the apparent easing of Cold War tensions in the 1970s with the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks, the balance of power between the two superpowers seemed to perpetuate a conflict that was ready to erupt at any moment. Far from dissipating, the anxiety provoked by the possibility of an atomic war thus continued to encourage the proliferation of utopias and dystopias as a means of imagining alternative futures and fostering intense contestation of the prevailing order. The awakening of ecological awareness, the Vietnam War, the fight for civil rights, decolonisation movements and myriad counter-cultural movements created a twofold dynamic from the 1960s onwards: a critique of the prevailing balance of forces (a critique of either capitalism or socialism), and a search for alternative cultural formulations from Eastern religions and mysticism (albeit through an exoticised and Eurocentric lens), or through an upsurge in interest in science fiction.[6]

Não obstante o aparente alívio das tensões da Guerra Fria na década de 1970 com a assinatura dos Acordos SALT, o equilíbrio de forças entre as duas superpotências parecia perpetuar um conflito sempre pronto a eclodir. Assim, longe de se dissipar, a ansiedade provocada pela possibilidade de uma guerra atómica continuava a incentivar a proliferação de utopias e distopias como meio de imaginar futuros alternativos e a fomentar uma intensa contestação da ordem vigente. O despertar da consciência ecológica, a guerra do Vietname, a luta pelos direitos civis, os movimentos de descolonização, os diversos movimentos de contracultura criam, a partir dos anos de 1960, um movimento dúplice: por um lado uma crítica ao equilíbrio de forças vigentes (seja com uma crítica ao capitalismo, seja com uma crítica ao socialismo existente); por outro lado, uma busca de formulações culturais alternativas, desde as religiões e misticismos orientais (ainda que através de uma leitura exotizada e eurocêntrica destas culturas), seja através de um recrudescimento da ficção científica[7].

Espiga’s imagery in the 1970s combines technology, science fiction, poeticism and cosmic mysticism in the creation of a utopia in which he seems to recognise art’s potential to reconnect people and create an alternative society. The Carnation Revolution of 1974 strengthened this belief in the possibility of social transformation, putting an end to the dictatorship of the Estado Novo, initiating decolonisation after years of colonial war, breaking the country’s prolonged isolation, and electrifying a decade of revolutionary hope.

Between Espiga’s attention to the rural world in the 1960s and the creation of a cosmic language in the 1970s, we see the expansion of a reflection on space and on the possibilities of creating community. If in the rural scenes of the 1960s he represented the joviality of a circumscribed community, in the 1970s not only did the literal space of his works expand – from the two-dimensional drawings and paintings, to sets for the stage and from there to the three-dimensional and performative occupation of architectural and urban spaces – but their symbolic ambition expanded, from the representation of a rural world to the creation of a cosmic symbolism. Underlying both is a deep belief in the possibility of creating community.

[1] The donation consists of 42 drawings, two study books, six sculptures, eight engravings and a catalogue book.

[2] See the article «Morreu Espiga Pinto, pintor do mundo alentejano», Público, 1 October 2014 (accessed on 10 June 2022).

[3] Espiga Pinto, Do meu início (1959-1966). Lisbon/Porto: Galeria de Arte São Mamede, 2010, n.p.

[4] The Ballet Gulbenkian only acquired this designation in 1975. The Gulbenkian Ballet Group had been created in 1965 and merged in 1975 with the Experimental Ballet Group of the Centro Português de Bailado (created in 1961), acquiring the name Ballet Gulbenkian. The FCG Archives contain other materials relating to set and costume designs that the artist created for the Ballet Gulbenkian, with which he collaborated between 1968 and 1982.

[5] You can see a record of this installation and performance (accessed on 20 May 2022).

[6] The aforementioned short film can be viewed (accessed on 20 May 2022).

[7] Although the literary production of science fiction goes back a long way, it had a major public impact in the 1970s through the production of several blockbuster films that popularised the genre and reached a much wider audience. We need only look back at some of the cinematic milestones from this period to get an idea of their impact on popular imagination: 2001, A Space Odyssey from 1968; Planet of the Apes from 1970; A Clockwork Orange from 1971; Solaris from 1972; Star Wars from 1977; Superman from 1978; and Stalker from 1979.