Summer Guests

Curators: Penelope Curtis and Leonor Nazaré

Summer Guests brings contemporary artists to the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum proposing new exhibition contexts that highlight crosscutting and unexpected relationships, and formal or conceptual proximity of works from different eras. Art works like the Mesopotamian low-relief, the Persian carpets, the showcase of Japanese lacquers or Turner’s The Wreck of a Transport Ship are thus enhanced by the challenge of being confronted with another time and other images which reflect contemporary modes and languages, also calling upon the timeless permanence of some causes. Fernanda Fragateiro will enhance with sculptural interventions some of the places where the events of the Summer Garden will be presented in addition to other locales selected by her.

About the event Download the exhibition map

Asta Gröting

Asta Gröting’s 'Bodenplatte', which has been placed close to Auguste Rodin’s sculpture Jean d’Aire, 'Le Bourgeois de Calais – L’Homme à la Clef', directly references the imaginary markings of the characters’ feet and questions the value of the base or the ‘ground’ of conventional sculpture. In Rodin’s studio in Meudon, Gröting found the mould for the base of 'Les Bourgeois de Calais' (the famous version that includes six characters) and filled in the empty spaces. She also wanted to examine the place of today’s bourgeoisie and the way in which art can handle this kind of questioning.

Bela Silva

In the same room as several attractively and neatly arranged Chinese ceramic pieces, Bela Silva’s contemporary ceramic pieces strike a disruptive tone, albeit one that initially appears to provide a certain continuity, in the zoomorphical and zoological figuration of the motifs, the typology of the pieces (vases, jars, fantastical animals), their decorative nature as ceramic pieces, whereby they diverge somewhat from the norm, and their chromatic palette. The dragons, in particular, are said to have been directly inspired by the Fo Dogs (Qing Dynasty) displayed in the large show-cabinet.

Diogo Pimentão

Diogo Pimentão’s cut out loop drawn with graphite takes on a certain decorative quality when placed near René Lalique’s mirror, which is itself strongly related to sculpture and drawing, and presents an unexpected three-dimensionality, presence and lightness. In both cases we find ourselves looking at knots and intertwined strands, a recurring motif in Art Nouveau, but also ubiquitous in the imaginary world of myths, from Mercury’s caduceus to the serpents that appear in so many legends, shamanic manifestations and the image of the labyrinth, which is often conceived of as a massive knot.

Fernanda Fragateiro

Fernanda Fragateiro’s sculptural interventions on benches designed by Ribeiro Telles highlight some of the spaces that serve as a venue for the Jardim de Verão events, along with other places especially selected by the artist. The artist’s approach often forges a connection with an architectural system based on architectural drawing, construction, installation and the demarcation of space. Her work uses the mirrored surfaces to highlight passages between the two-dimensional planes of the image and the three-dimensionality of the space, the virtual ‘screens’ that multiply it, the sensory experiences of thermal and tactile change, the striking interruption of limits and outlines by others that overlap them, and the aesthetic examination that is also demanded by practical enjoyment.

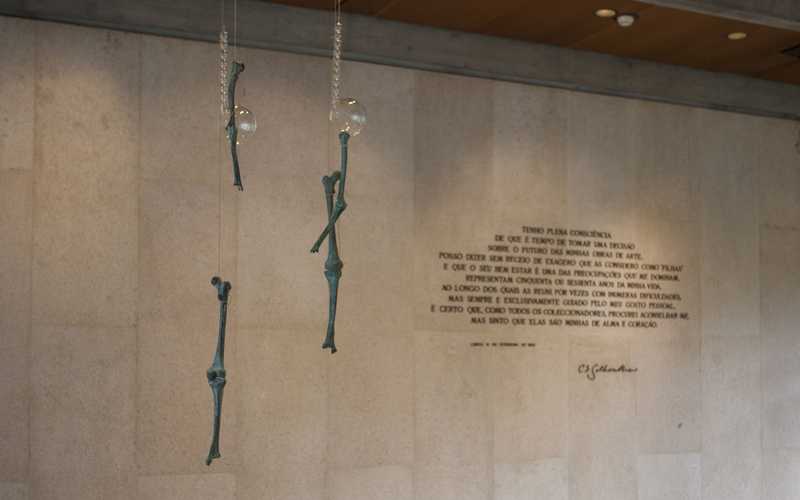

Francisco Tropa

On the plinth of the absent sculpture of Jean-Antoine Houdon’s 'Apollo', the suspended, fragmentary figure made of glass bones and ‘organs’ by Francisco Tropa emphasises the rising movement that is characteristic of this Greek god, that great traveller moving across the immense vault of the heavens. The sudden lightness and transparency of the glass creates a contrast with the heaviness and opacity of the bronze, suggesting different destinies effected upon the decomposition of the body parts, and proposing a memento mori for all Vanitas.

Miguel Branco

Miguel Branco’s sculpture paraphrases the statuette of the official Bes, from Late Period of ancient Egypt. The artist was directly inspired by this figure, and his work makes reference to the statuette’s position and bearing. However, he replaces the intelligent face of the figure with the hominid contours of an almost simian head, on the very threshold of animalism and primitivism. The relationship with death and writing (in the same room we find the stele of another scribe), two fundamental aspects of Ancient Egypt, are thus evoked in this contrasting representation of what might be seen as the rise and ‘fall’ of the human being.

Miguel Palma

Miguel Palma uses an Empire-style vase to challenge assumptions about the museum as a place of conservation and the protection of heritage: an electric mechanism at the base of the object makes it move at one-minute intervals, allowing time for visitors who are perusing the show-cabinet of 18th-century porcelain to be surprised by it. The joke can be taken at face value, yet the movement also echoes the way in which the vase was made, as well as the action of the human hands that have carried it from place to place. The show-cabinet and the plinth thus cease to be the sort of safe places that are associated with museums, instead issuing a shock to our tendency to idealise such institutions.

Patrícia Garrido

Interior is not only the name given to the rubber and metal piece by Patrícia Garrido, but also relates to the nature of the pieces that the artist presented at the Museu do Chiado in 1995 and the issues raised by them. These include a kind of bag in the shape of a flower, which, like other pieces in the same series (Jogo de Damas), has a probable sexual resonance. Positioned close to the 16th-century velvet embroidered silk parasol, it evokes a feminine realm due to the pieces’ fortuitous harmony in colour and material.

Pedro Cabral Santo

Pedro Cabral Santo’s film 'Turner Pic' appears below Turner’s 'The Wreck of a Transport Ship', thus allowing the artist to superimpose a dialogue about UFOs and aliens, featuring RGB colour bars, a system traditionally used to aid communication with deaf-mutes. The artist has created this from a truly surprising dialogue in relation to this picture within the Gulbenkian Museum, such that the textual substance of his piece provokes a sense of strangeness, while also overlaying codes and replicating the way in which public reception adds something to every work.

Susanne Themlitz

In the area devoted to 18th-century furniture, the two pieces by Susanne Themlitz convey an experience of integration that is as unexpected as it is effective, at once timeless and deeply evocative of its era. The first is an abstract painting (Respiração. Pausa – entre dois pontos; ‘Breathing. Pause – between two points’) featuring strong colours and planes, which the artist describes as a ‘permeable landscape and suspended transformation’. The second piece is a table bearing objects (a mirror, an amethyst, a globe, a wooden rule and a pane of glass) – an iconological reference to the scientific achievements of the Renaissance and Enlightenment, with a surreal slant that places it within the same realm and aura of refinement as the pieces of furniture that surround it.

Vasco Araújo

Four series of drawings by Vasco Araújo line the corridor that leads visitors from the area devoted to the art of the Far East to that of European art. Pink Family, Green Family, White and Blue Family, and Armorial Family (echoing the names of the Chinese ceramics that visitors have seen in the room that they have just left) are almost imperceptible drawings of damaged vases and goblets unearthed during archaeological excavations. The artist pairs these with extracts from Susan Sontag’s book Regarding the Pain of Others. This association suggests a powerful metaphor for art, time, languages and tangible and intangible heritage.

Wiebke Siem

Wiebke Siem’s massive carpet beater, which is suspended over an Indian rug, matching it for sheer size, robs the decorative object of its almost sacred aura, reducing it instead to its practical and utilitarian dimension. In doing so, Siem makes direct reference to a series of photographs by Hans Bellmer in which the shadow of this object, which is common in German homes, dwells alongside various ‘dolls’, while also prompting an association with the shadow in the films of Murnau, or with other famous carpets, such as the one found in Freud’s study. Yet it mainly refers to the place of women in the home, calling roles, emotions and archetypes into question.

Yael Bartana

From a common geographical region, the Middle East, emerge a Mesopotamian bas-relief and an animated film by the Israeli artist Yael Bartana. The first, a figure of a winged genie with the attire of a warrior; the second, soldiers and policemen from that troubled region, digitally transformed into ‘clay’ characters that move like reliefs in the formless and uniform environment of war. Geography and formal similarity draws them together, yet it is also important to highlight the radical difference in the idea of combat (magical initiation in the first case) that distinguishes them.