About the Collection

His wide-ranging collection covers various periods and areas: Egyptian, Greco-Roman, Islamic and Oriental art, old coins and European painting and decorative arts.

The phrase ‘only the best’ accurately defines the criteria by which he was guided, and the passionate affection he developed for the objects.

His pieces were acquired through intermediaries, directly from public and private owners, or at auctions. Calouste Gulbenkian, despite his definite tastes, surrounded himself by personalities whom he trusted and who counselled him. It was Sir Kenneth Clark, at that time director of the National Gallery in London, who advised him to buy Manet’s Boy Blowing Bubbles. André Aucoc, Paris jeweller and goldsmith, played a pivotal role in the negotiations with the Soviet Government to buy important pieces from the Hermitage Museum in Leningrad in the two-year period from 1928 to 1930.

When the oil magnate grew tired of an object he would remove it from his collection by giving it away as a present, exchanging it or using it in part-payment for something else.

Gulbenkian was also interested in enriching public collections, he contributed most generously either by financial aid or by donating pieces to cultural institutions such as the Louvre in Paris, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga in Lisbon.

In 1938, with the sections of his collection in place, Calouste Gulbenkian expressed his interest in creating an institution in London, next to the National Gallery, that would be able to house the collection in its entirety. This included some of the greatest works of art in his collection recently placed on loan to the National Gallery, and Egyptian antiquities in the British Museum.

The project came to nothing with the outbreak of the Second World War. A diplomatic incident that took place in 1942, led the British government to declare Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian a ‘technical enemy’, a classification that was revoked the following year, though it was one Gulbenkian never forgot.

In 1947, with the National Gallery restored after damage caused by German bombing raids, the new director Sir Philip Hendy requested permission to exhibit the paintings from the collection loaned in 1938. Gulbenkian refused as the previous director, Sir Kenneth Clark, in whom the Collector had total confidence had resigned. In the same year, Sir Leigh Ashton, the director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, approached Gulbenkian with a suggestion for the creation of a museum in London to house the entire collection. In 1947, exactly the same invitation was put forward by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D. C., which proposed to exhibit all the works deposited in London. In 1948, the Egyptian antiquities from the British Museum were sent to the United States. These were followed, in 1950, by the paintings that had been on loan in the National Gallery in London.

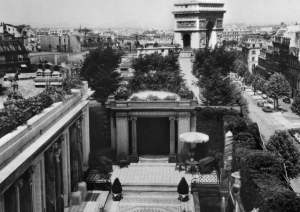

The majority of the collection remained in his house on the Avenue d’Iéna, in Paris, a property he acquired, in 1922, from the collector Rodolphe Kann and which, for four years underwent extensive adaptation to install his works of art.

When Calouste Gulbenkian made his definitive will in Lisbon on June 18th, 1953, he specified that his works of art should come to Lisbon, and along with the Foundation to be instituted, a museum should also be built to protect and exhibit the collection. The project for a museum and foundation that had been planned for London and pondered over by Washington was put into operation in Lisbon.

While proposals for the construction of the museum and foundation headquarters were being studied, the 18th century Palácio Pombal at Oeiras, near Lisbon was prepared to house the works of art that mainly came from London, Washington and Paris.

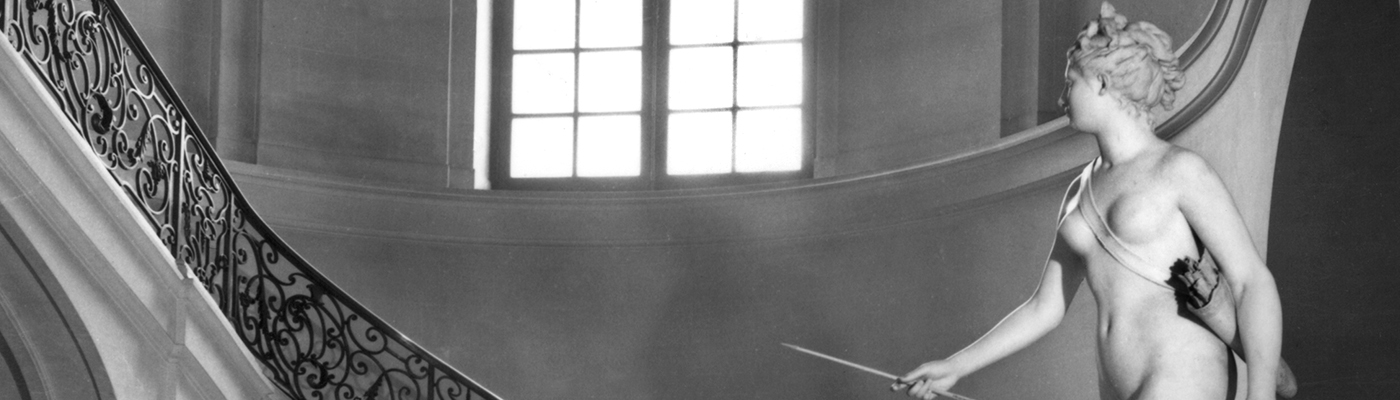

Negotiations with the French Government were extremely complex particularly when it came to priceless masterpieces from the royal palaces at Versailles and Fontainebleau, as well as the Houdon sculptures from the Gulbenkian residence in the Avenue d’Iéna, in Paris. A combined legal and diplomatic effort was made by the administration of the Gulbenkian Foundation, in conjunction with the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and André Malraux, then French Minister for Culture. This enabled the rest of the collection to be shipped, with no restrictions, to Lisbon where it arrived on 16 June 16 1960.

For the first time, the 6,440 objects acquired by Calouste Gulbenkian were finally together under the same, albeit temporary, roof just as he had always wished. In the succeeding months a number of items from the collection were shown to the Portuguese public at various exhibitions that took place at the beginning of the sixties. On July 20th, 1965, to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the death of the founder, 300 objects from the Gulbenkian collection were put on permanent display to the public. In 1969, the works of art left the Palácio Pombal for the new museum, at last grouped together as an entity.