Power of the Word IV

Divine Wisdom: The Sufi Way

Event Slider

Date

- Closed on Tuesday

Location

Calouste Gulbenkian MuseumMy heart has become capable of every form:

it is a pasture for gazelles and a convent for Christian monks,

And a temple for idols and the pilgrim’s Kaaba

and the tables of the Torah and the book of the Quran.

I follow the religion of Love:

whatever way Love’s camels take,

that is my religion and my faith.

This poem comes from The Interpreter of Desires (Tarjumān al-Ashwāq) by the Sufi master Ibn ʿArabī (Murcia 1165 – Damascus 1240). His words transmit the universal message of love of Sufism, the mystical heart of Islam. The Sufi spiritual path is practiced by Muslim men and women around the world, and explored here through five key themes: Wisdom, Unity, Love, Path and Plenitude. The works on display in the gallery originate from India to Portugal, including from Afghanistan, Iran, Syria, Egypt and Turkey.

Words are doors

Sufism is the mystical dimension of Islam, whether understood as a spiritual path or as the inner teaching of Islam. In Arabic - the sacred language of Muslims - the word taṣawwuf, or Sufism, has a complex and sometimes dubious etymology, which accrues fundamental aspects of Sufism itself. Hypotheses for the origin of the word include images and ideas around covered shelter (ṣuffah), wool (ṣūf), purity (ṣafāʾ), and, according to some, wisdom (sophía). These words form the basis of this brief introduction to some of the main aspects of Sufism.

God’s friendship

A key concept in Sufism is nearness or proximity, the search for intimacy with God. The first Sufis were referred to as ‘the people of the shelter (ṣuffah)’, an expression that alludes to the origins of Islam and the people who gathered in Medina under a shelter adjacent to the mosque of Muḥammad (570-632), the prophet of Islam. By virtue of their physical proximity to Muhammad, they received the teachings directly from their guide. Since then, great Sufis such as Rābiʿa (718-801) and Rūmī (1207-1273) have been called awliyāʾ Allāh, i.e., close friends of God.

Light of the heart

The heart (qalb), mentioned more than one hundred times in the Quran, is referred to as the ‘throne of God’ in a saying from Muḥammad and as a mirror for Divine Light (Nūr) in Sufi poetry. The heart is where the sacred and primordial nature (fiṭrah) of all humanity resides. It is the receptacle of mystical visions and words of guidance. The heart is the true 'organ' of knowledge. Indeed, Sufism escapes rational definitions. Words can only allude to its true meaning.

Path of transformation

The early mystics of Islam are reported to have dressed humbly, in clothes made of wool (ṣūf). Humility is another key aspect of Sufism and the Sufi is often called a dervish or faqīr, i.e., poor. Individual transformation of the ego (nafs), or the most ignorant and obscure facets of one’s being, is essential to the Sufi way. Along this spiritual path, the ego passes from a condition of temptation and rebellion to peace and inner purity (ṣafāʾ).

Outer way and inner way

Sufis seek Unity and Oneness of God (tawḥīd), through an initiatory path or inner way (ṭarīqa). Without abandoning religious practices of Islam, faith and external life, the follower seeks spiritual and inner excellence (iḥsān) as preached by Muḥammad. Achieving this path requires sincerity, devotion, love, and the orientation of a guide (murshid).

Divine Wisdom

However dubious the link, some people have attempted to establish a connection between the word Sufism and the Greek sophía or wisdom. Sufis certainly seek wisdom - that is, knowledge which comes from direct experience, knowledge of Divine Reality, which goes beyond the illusory duality of the world and the mind. This corresponds to a mystical union, or a loving annihilation (fanāʾ) of the ego in the Divine, which enables the subsistence (baqāʾ) of the soul in God.

Circles of remembrance

Sufism is not only an individual path; community life also plays an important part. Sufis do not isolate themselves from the world. Instead, they seek to cultivate their personal development within Sufi orders, inside their families and in society, without abandoning either employment or connecting with others. Both individual and collective practices exist in Sufism. An example is dhikr, the remembrance of God, which commonly comprises the rhythmic repetition of the names of Allāh. In collective dhikr gatherings, this repetition can also be accompanied by music and dance. Whirling dancers is a common image associated with Sufism. This practice occurs in certain Sufi orders, especially those associated with the Persian poet and sage Rūmī.

Art, Beauty and Majesty

Music, dance, poetry, calligraphy and other arts are expressions of Divine Beauty and Majesty. Sufi love poems frequently refer to the cup and wine, as metaphors for the complementarity and lack of separation between exterior religious practices (cup) and inner spiritual ecstasy (wine). The Sufi finds Beauty in everything, when their ego is finally pacified and their heart is a polished mirror that reflects Divine Light. Everything which exists is a manifestation of the Divine, the One, who is indescribable and intangible, ineffable and beautiful, majestic and merciful.

Topics

Unity

Love

Path

Plenitude

-

Wisdom

Who knows their own soul, knows God (Allāh). According to Sufis, this teaching was delivered by Muḥammad (Mecca, 570 – Medina, 632), the prophet of Islam, considered the greatest spiritual guide in the Sufi tradition.

Sufism (taṣawwuf) is a path of wisdom, in which everything simultaneously conceals and reveals the Divine: in life, the cosmos, and in us. Knowledge of God comes through the heart (qalb), a keyword in Sufism, mentioned in a poem by the Amazigh imam al-Būṣīrī (see images below).

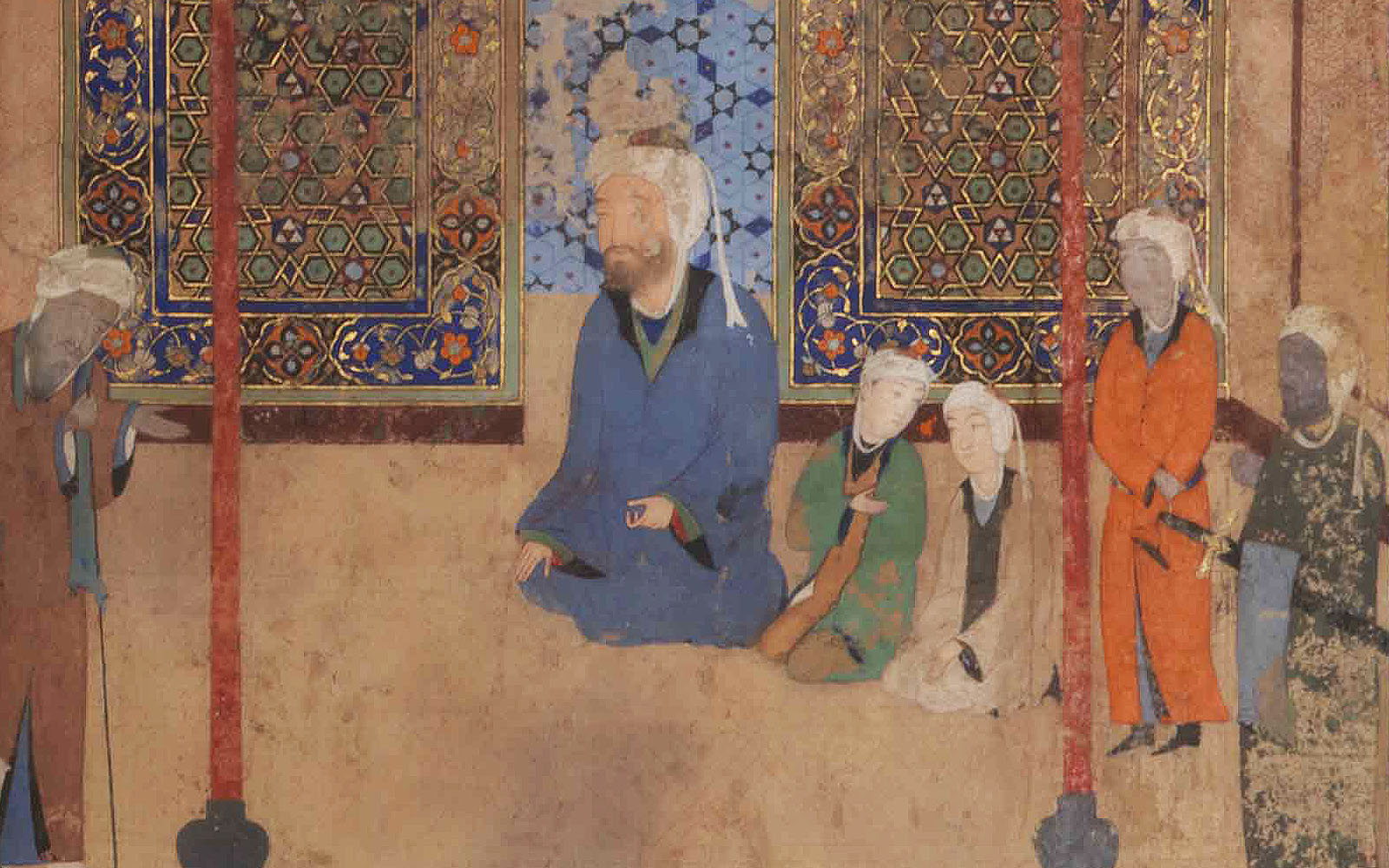

Sufi men and women seek this knowledge of the heart. Among them is the Persian poet Ḥusayn Kāshifī, depicted holding Islamic prayer beads (tasbīḥ), in one of the images showed below this text.

«A Oferta ao Imperador: Círculos das Ciências e Tabelas dos Números» (Tuḥfat al-Khāqān:Dawāʾir al-ʿulūm wa-jadāwil al-ruqūm), fols. 2r-1v. Museu Calouste Gulbenkian An ascetic in a cave India, 1610-1620 Ink, watercolour and gold on paper Calouste Gulbenkian Museum A prince seeks guidance and blessing (barakah) from a spiritual guide who lives in a cave.

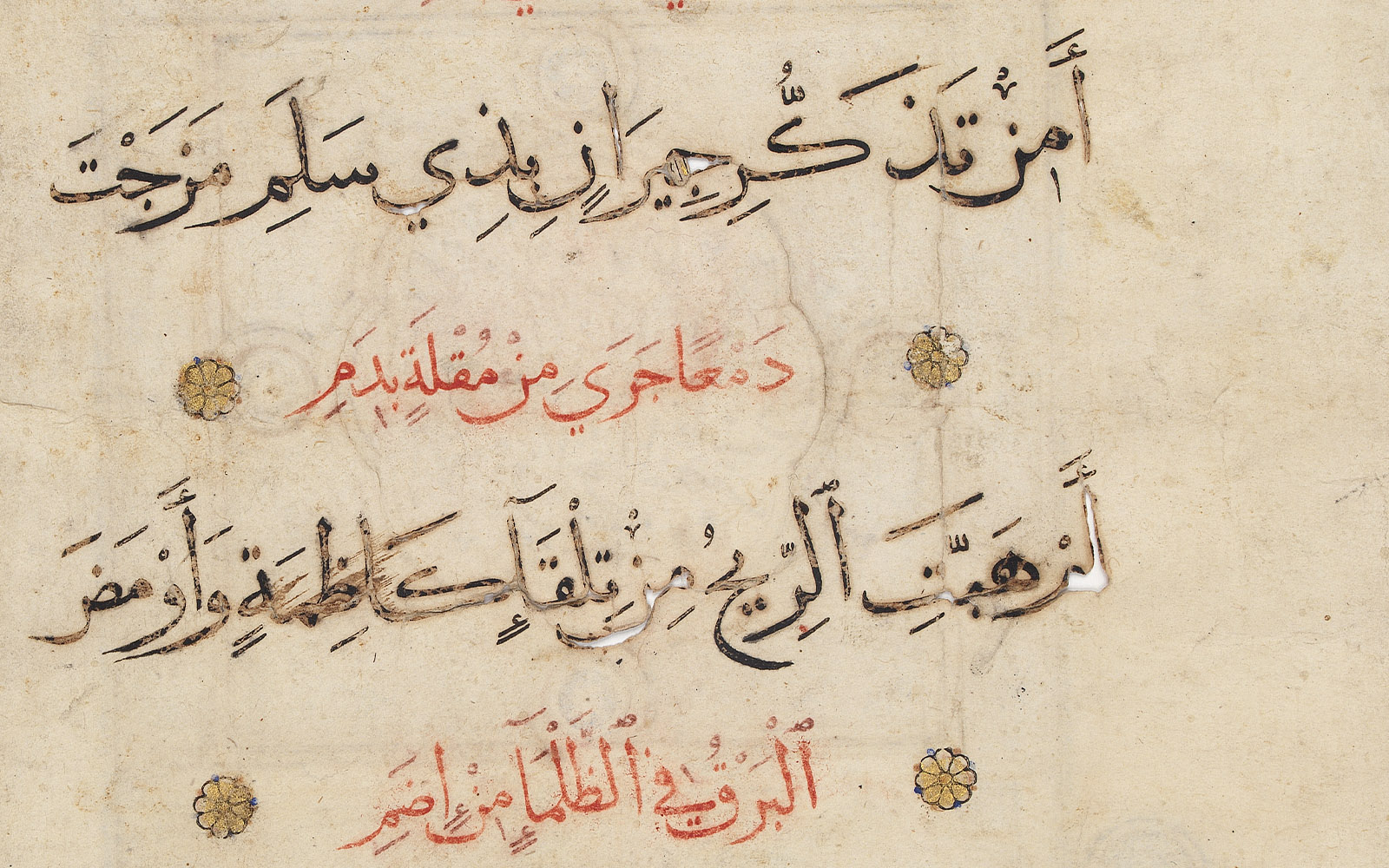

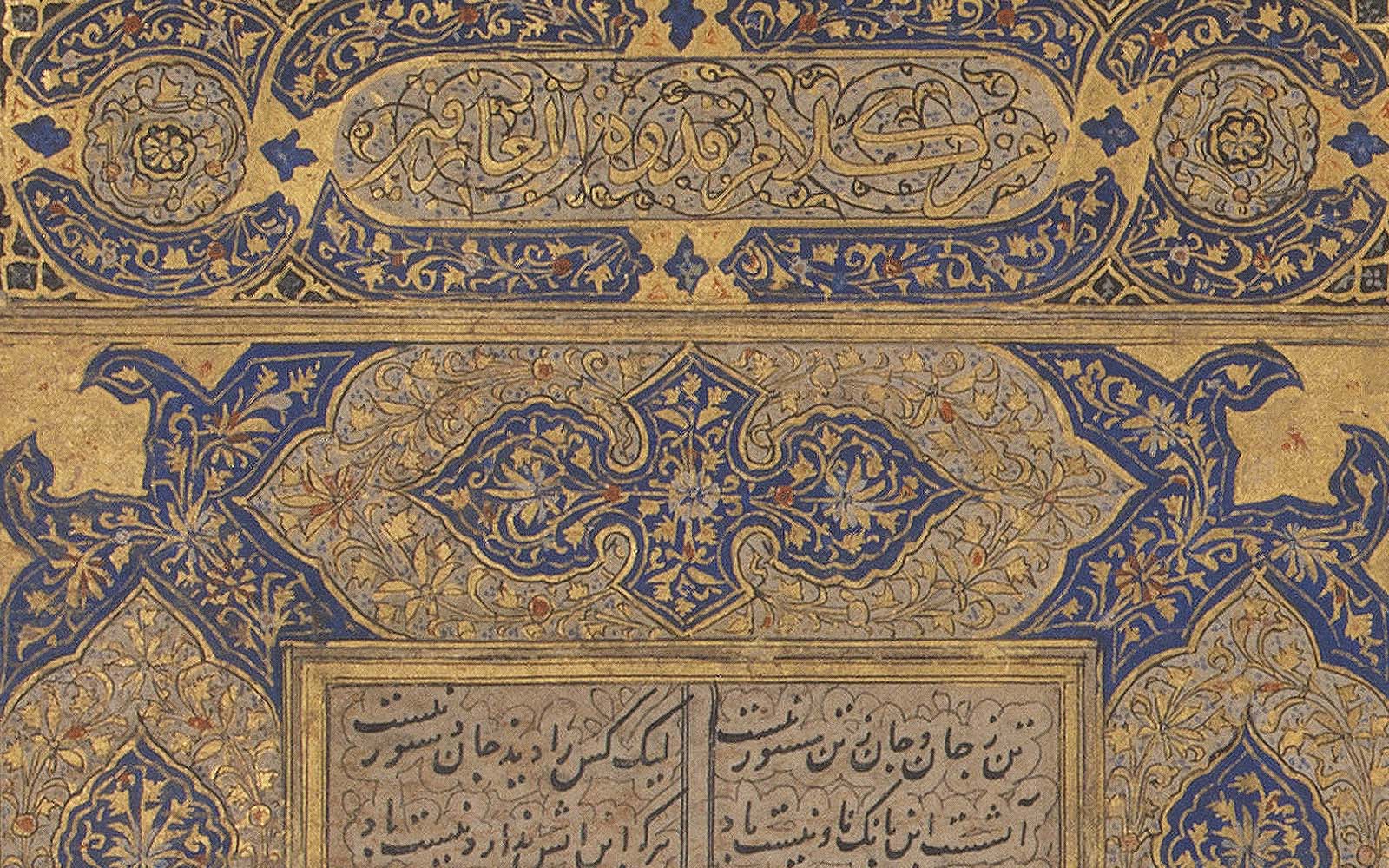

Qaṣīdah al-Burdah [Poem of the Mantle] by al-Būṣīrī (1212-1294) Egypt, 15th century Ink, watercolour and gold on paper Inv. M42 ‘Singing the beloved. Known as The Poem of the Mantle’, al-Būṣīrī’s celebrated Sufi work was originally titled The Celestial Lights in Praise of the Best of Creation. The poem is dedicated to Muḥammad, prophet of Islam, and beloved of the Sufis.

Kamāl al-Dīn Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī Kāshifī? [detail](1436-1504).Iran, 17th century. Ink, watercolour and gold on card. Calouste Gulbenkian Museum The legacy of the word. Ḥusayn Kāshifī, known as the preacher (al-wāʿiẓ), was, in addition to being an intellectual, poet and Sufi, the translator of the Persian fables Kalīla wa Dimnah, which were the subject of the second exhibition of Power of the Word on Fables in 2020

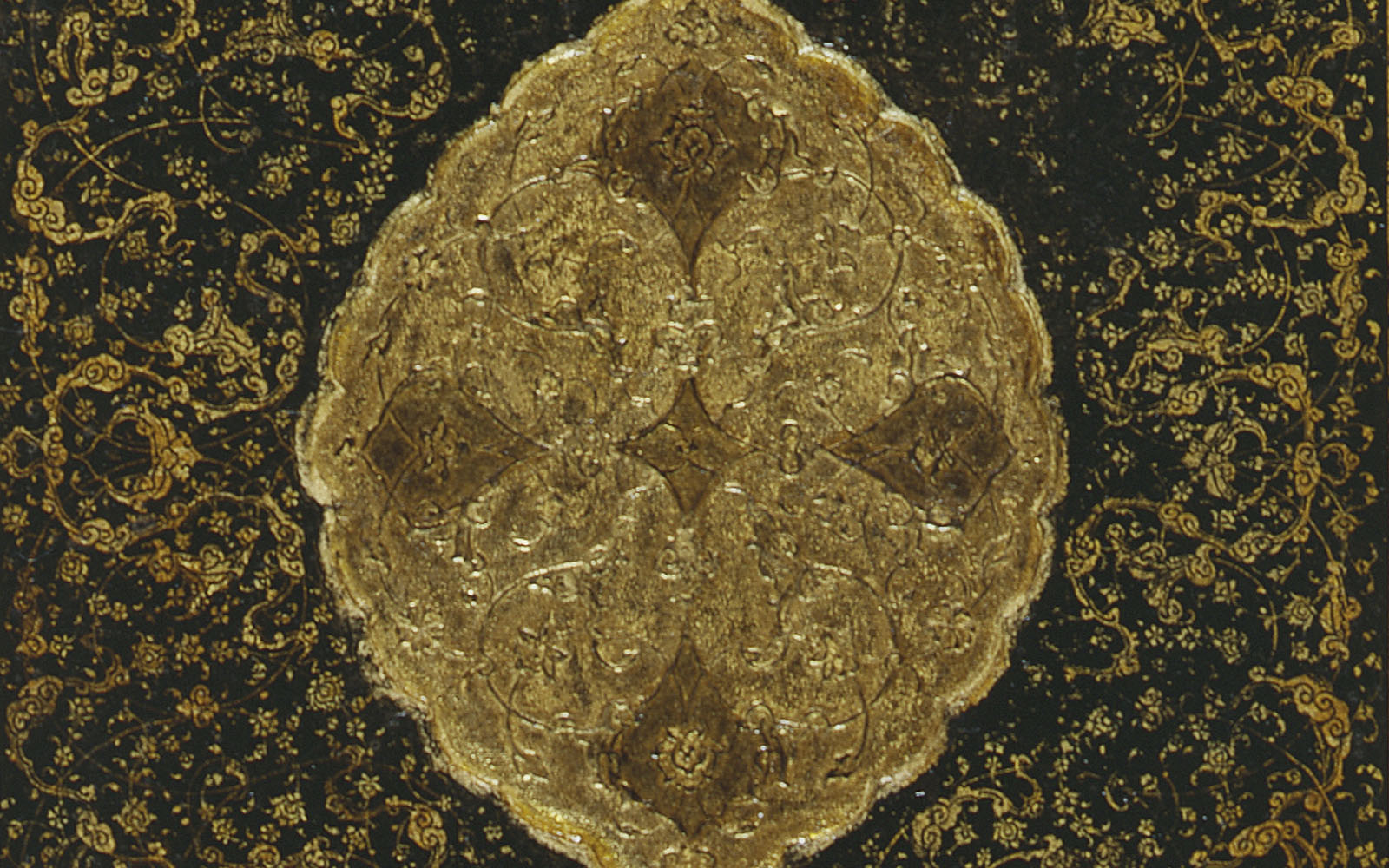

Dīwān [Songbook] by Ḥāfiẓ (c. 1325-1390) Afghanistan, Herat, 16th century Painted and varnished papier mâché boards Calouste Gulbenkian Museum The great Sufi poets, such as Ḥāfiẓ, are considered spiritual teachers.

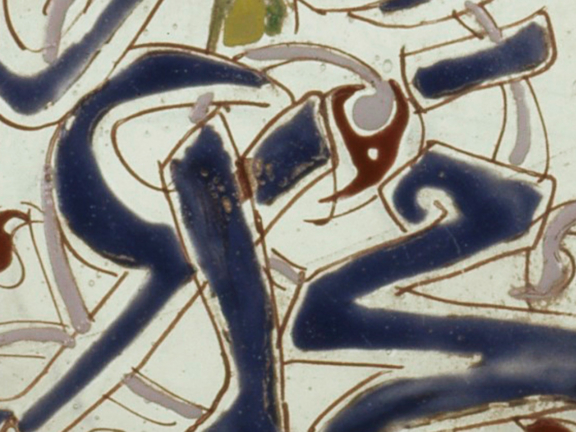

Tile panel with prunus trees in moonlight Turkey, Iznik, c. 1580, Ottoman period Stonepaste, painted under the glaze Calouste Gulbenkian Museum I hear the taste of fruit. To taste the fruit of the plum tree, one must wait patiently for summer and then savor the moment. Being patient and contemplating the present are two attitudes cultivated in Sufism, as keys to spiritual fulfilment.

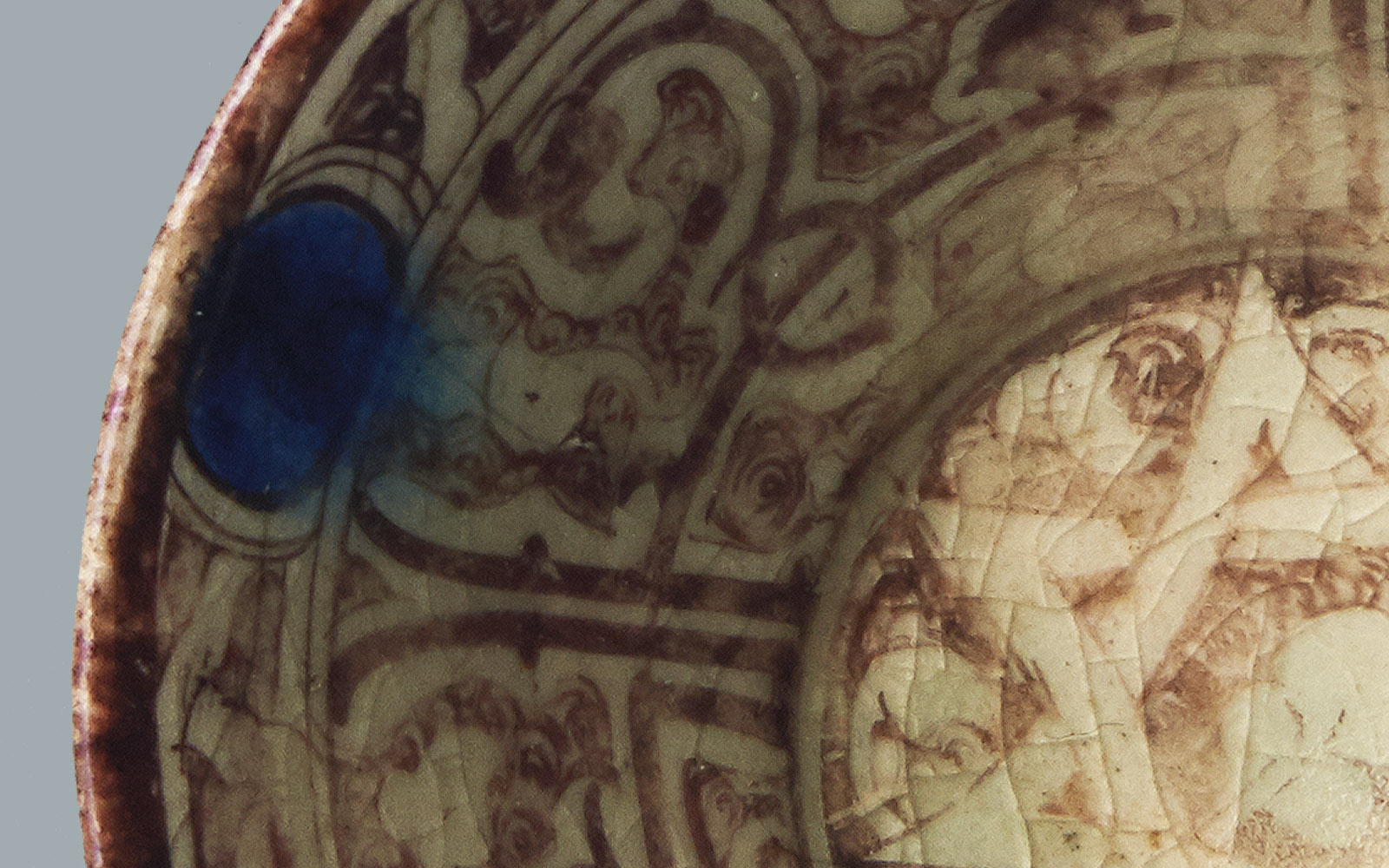

Bowl with seven-pointed star. Syria, Raqqa, late 12th - early 13th century, Zengid and Ayyubid periods Stonepaste, painted under and over the glaze in lustre. Calouste Gulbenkian Museum The star in this cup has seven points. In the Islamic rosary, the same number is counted by a special bead. Seven is also the number of the opening verses of the Quran. However, the true meaning of Sufism cannot be expressed in words, only known intuitively by the heart.

-

Unity

In one of the most celebrated poems of the Persian Sufi Rūmī, the flute laments its separation from the reed from which it originated (Spiritual Couplets). This metaphor refers to the desire for mystical reunion and the longing for Divine Unity, beyond all illusory duality. The dance of the whirling dervishes is another dynamic and corporal expression of this ardent desire for union.

For Sufis, the search to approximate, ever more closely, the mystery of Divine Unity is a path of excellence and benevolence (iḥsān). This is the straight path (ṣirāṭ al-mustaqīm) referred to in the opening chapter of the Quran. Sufi poetry, with its spiritual symbolism, is a mystical form of interpreting the Quran.

Opening folios of a Quran Turkey, Istanbul, second half 16th century Ink, watercolour and gold on paper Calouste Gulbenkian Museum Hearing, knowing. These folios contain, in addition to the first chapter of the Quran, another verse from the holy book of Islam (II, 137) in which two of the ninety-nine names of God appear: al-Samīʿ (The All-Hearing), al-ʿAlīm (The All-Knower), which are meditated upon by the Sufis.

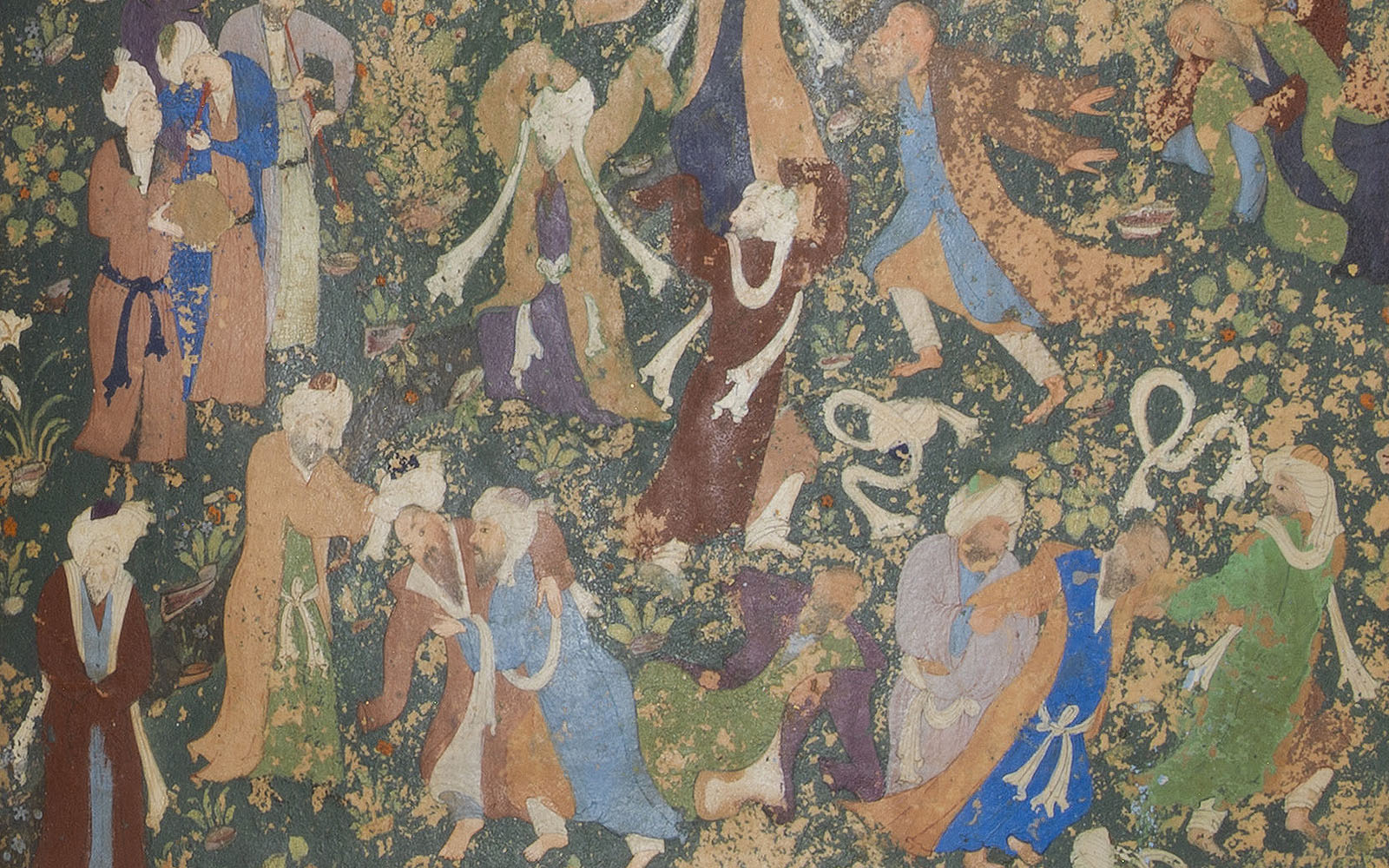

<i>Gulistān</i> [Flower Garden] by Saʿdī (c. 1210-1291) Iran, Shiraz, 1536-1537 (AH 943) Ink, watercolour and gold on paper Calouste Gulbenkian Museum ‘The All-Hearing’ is one of the Names of God: al-Samīʿ. From the same etymological root, samāʿ, or hearing, is the ritual gathering with music and dance practiced in some Sufi orders. This is depicted in this illustration of a work by the Persian poet Saʿdī.

<i>Mathnawī Maʿnawī</i> [Spiritual Couplets] by Rūmī (1207-1273). Iran, Shiraz, 1419 Ink, watercolour and gold on paper Calouste Gulbenkian Museum ‘Who hath seen a poison and an antidote like the flute?’, asks Rūmī. In Sufism, the transformative and healing power of spirituality engages the human being holistically.

Mosque lamp Egypt, 14th century (before 1341), Mamluk period Made for Sultan Nāṣir al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Qalāwūn (r. 1293-1294, 1299-1309 e 1310-1341) Gilded and enamelled glass Calouste Gulbenkian Museum This point of light illuminates. The Arabic words around the rim of this lamp read: God (اَلله, Allāh) ‘is the Light of the heavens and the earth’. This is the

Pharmacy container, analogy of healing the soul. Syria or Iran, 14th century. Stonepaste, painted under the glaze Calouste Gulbenkian Museum ‘Alchemy’. Sufism can be interpreted as an alchemical work of inner transformation of the soul. Some Sufis cultivate the sciences of the cosmos, such as Ḥusayn Kāshifī, poet, Sufi and astronomer

-

Love

A recurrent theme in Sufi poetry, love (ʿishq) is wine, a metaphor for spiritual ecstasy which intoxicates those who seek wisdom. Wine red is the colour of the silk thread in a carpet which is showed in one of the following images, as well as of a velvet cloth inside the tomb of Muḥammad. In Sufism, the prophet is known as the beloved (ḥabīb) and teaches that God is above all loving: ‘My mercy surpasses My strictness’.

In the Sufi poetic context, the crazed lover (majnūn) is he who transforms his life to unite with his beloved Laylā. These two characters, Laylā and Majnūn, express the loving attraction that transforms and leads to symbolic and initiatory death, or extinction (fanāʾ) of the ego in divine, infinite and eternal love.

Niche carpet [detail]. Turkey, 1900. Silk Calouste Gulbenkian Museum A hidden treasure. Looking at this red silk carpet, we recall that a narration (ḥadīth) from Muḥammad shares that a red velvet cloth was placed inside his tomb. ‘I was a hidden treasure, and I wished to be known,’ says God, in another ḥadīth.

Majnūn bending over Laylā’s tomb. Anthology of Sultan Iskandar (r. 1409-1414). Iran, Shiraz, 1411 (AH 813) Ink, watercolour and gold on paper Calouste Gulbenkian Museum Love without borders. A classic work of Arabic, Persian, Islamic and Sufi literature, the story of the lovers Laylā and Majnūn has been compared to William Shakespeare’s play Romeo and Juliet, owing to multiple similarities.

Ṣifāt al-ʿĀshiqīn [The Qualities of Lovers] by Hilālī (c. 1470–1529) Iran, Qazvin or Mashhad, 1568 (AH 976) Ink, watercolour and gold on paper Calouste Gulbenkian Museum Three drunks are brought before the king. One excuses himself saying he is afflicted by divine love. The king agrees that ‘wine soothes the pain of love’, a metaphor of Sufi mystical drunkenness, by the Turkic-Afghan poet Hilālī.

‘Separation has driven sleep from my eyes’. This verse, on the outside of the cup, from the Arab poet al-Mutanabbī (c. 915-965) sings of separation and loving desire, echoing Sufi themes.

Barefoot. The worn areas on this carpet reflect its use in prayer. For Muslims this practice involves physical movements such as prostration. The contact of bare feet with the carpet is an intimate sensorial experience, which, at the same time, is a return to a natural, humble and bared condition of the soul.

-

Path

Life is a path of discovery and wonder, but also one of patience and perseverance: the Sufi knows that the rose has perfume, but also thorns. A true Sufi is he or she who tames their ego (nafs) through the challenges of life and polishes their heart like a mirror, so it reflects Divine Light (Nūr).

The centre of the rose hides the secret of its fragrance. And so, the Sufi way (ṭarīqah) connects the outer dimension of life to its inner essence. It is an intimate journey of transformation: departing from a condition of ignorance to achieving the highest levels of wisdom and peace (Salām).

So that the fragrance may spread, throughout humanity and the universe, like a stream of wisdom and love.

Tile with two roses [detail]. Turkey, Iznik, 16th century. Stonepaste, painted under the glaze. Calouste Gulbenkian Museum A light flowery scent. ‘Take a leaf from my rose-garden. A flower endures but five or six days, but this rose-garden will always delight.’ (Saʿdī)

Prayer niche (<i>miḥrāb</i>). Iran, Kashan, 13th to 14th century, Ilkhanid period Stonepaste, moulded and painted under and over the glaze with lustre. Calouste Gulbenkian Museum A guiding niche. Walking a path implies navigating and overcoming fears. One of the inscriptions in this prayer niche reads: ‘Do not be afraid and do not grieve’ (Quran, XLI: 30).

<i>Būstān</i> [Orchard] by Saʿdī (c. 1210-1291). Uzbekistan, Bukhara, 1549 (AH 956). Ink, watercolour and gold on paper. Calouste Gulbenkian Museum Although this manuscript was damaged in the 1967 floods, it has preserved the vitality of its figurative and Sufi elements: on the right, contemplative and ecstatic dervishes are depicted, including Persian poets, such as perhaps Jāmī and Ḥāfiẓ. ‘The treasure lies in the ruins’, teaches Rūmī.

Invitation. ‘Come! For the rose tree is aflame with the fire of Moses, so that you may learn from the bush the subtlety of Unity.’ (Ḥāfiẓ)

Beaker with flying birds Egypt (or Syria), first half 14th century, Mamluk period. Gilded and enamelled glass. Calouste Gulbenkian Museum At last they discovered what dwelt in the heart. The vibrant scene on this beaker has been interpreted as a visualization of the Sufi poem, The Conference of the Birds, by the Persian poet ʿAṭṭār (c. 1145-1221). Led by a hoopoe, the birds of the world set out in search of the legendary Sīmurgh, the king of birds. At the end of a long and arduous journey through seven valleys, each of increasing difficulty, only thirty birds remain.

The Sīmurgh king then reveals that what they have been seeking is within themselves: ‘I am a mirror before your eyes’, says the king, ‘and all who stand before me see themselves, their unique reality’. The journey, thus, represents the inner transformation of the Sufi towards mystical union with God. ʿAṭṭār’s choice of the number thirty is a clever play-on-words: for ‘Sīmurgh’ in Persian means thirty (sī) birds (murgh).

-

Plenitude

In Sufism, a lively and dynamic dialogue exists between the complementary. This dialogue is explored in this exhibition through containers – a jar, some cups, a box – whose contents achieve their highest value when they are gifted. Sufis are vehicles of gift-giving through their openness to share spiritual and beneficial wisdom.

A game of complementary elements inspires the work of Portuguese artist Sara Domingos (1973-), Giving water yields the best reward. Water stands out here as a primordial element of life and of sharing.

In the mirror box displayed in one of the images below, women and men entertain themselves with cups and music. The feminine plays an essential role in Sufism. Rābiʿa (c. 718-801), the celebrated Arab female Sufi master, wanted to ‘pour water on hell’, so people would not worship God out of fear of punishment, but out of desire for His Beauty.

Another synthesis is found in a copy of Jāmī’s Spring Garden: some of its images evoke both the communal dimension of Sufism and the individual aspiration to ascesis. One of the human figures rises from the ground to the sky, like a cypress, a Sufi image of the complete human being (insān al-kāmil), who connects heaven and earth (see images below).

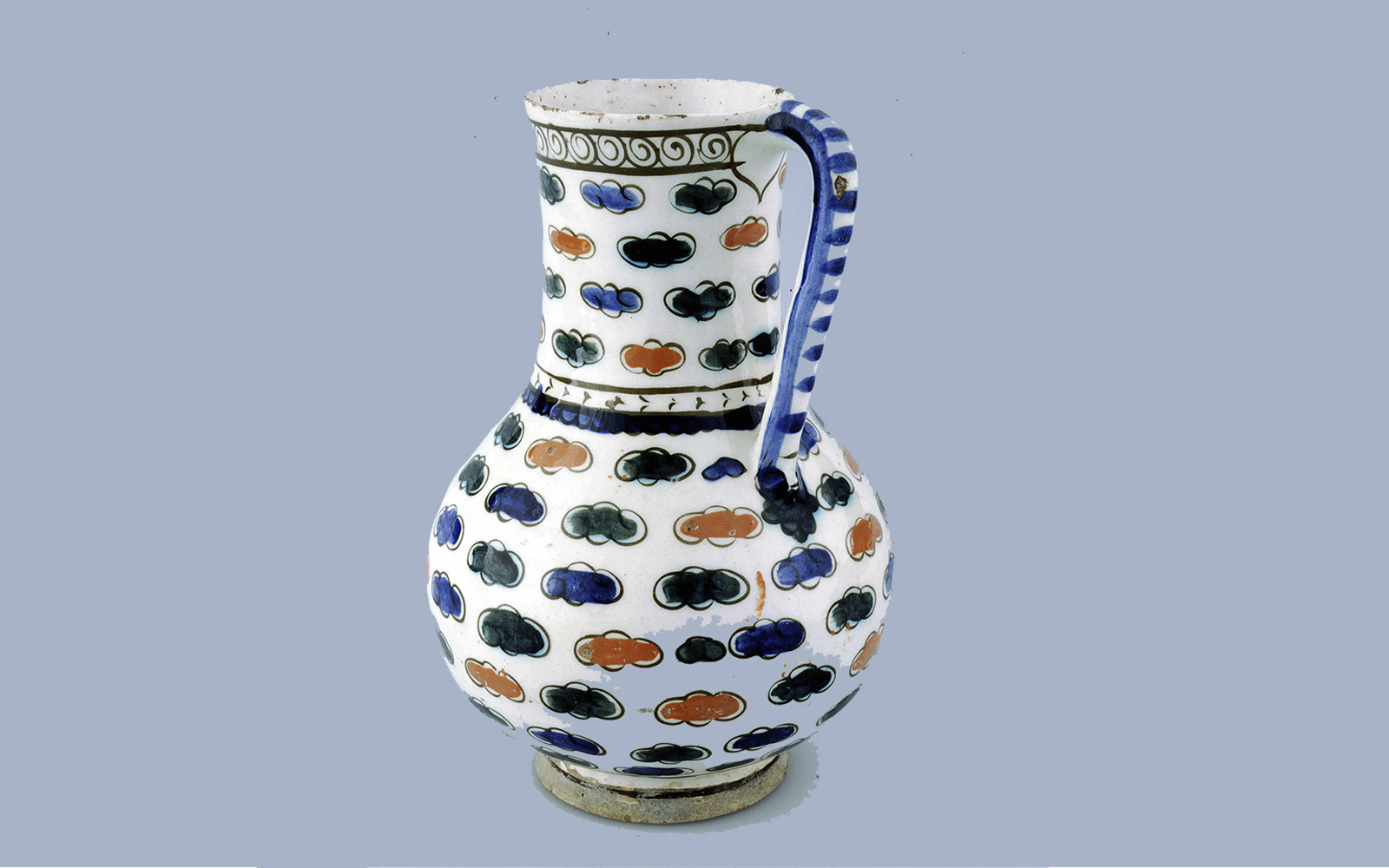

Jug with water clouds. Turkey, Iznik, c. 1590-1600. Stonepaste, painted under the glaze. Calouste Gulbenkian Museum Through the clouds. ‘The life of this world is like the rain sent down from the sky.’ (Quran, X, 24))

<i>Bahāristān</i> [Jardim da Primavera] de Jāmī (1414-1492). Iran, first half 16th century. Ink, watercolour and gold on paper. The poet Jāmī followed the school of thought of the great Sufi master Ibn ʿArabī, as well of the teachings of the Naqshbandī Sufi order, one of the most active in the world.

Mirror box and cover. Iran, 19th century. Lacquered pasteboard. Calouste Gulbenkian Museum The mirror. ‘Do you know why the mirror of your soul reflects nothing? Because the rust has not been cleared from its face.’ (Rūmī)

Velvet [detail]. Turkey, 16th century, Ottoman period. Silk. Calouste Gulbenkian Museum Whirling. Twelve sets of three crescent moons and one star. Patterns are bridges to the spiritual realm. The visual rhythm of geometry weaves subtle vibrations that reverberate and soothe the body, soul and heart.

Sara Domingos (1973-). <i>Giving water yields the best reward</i>. Glazed earthenware; oil on cotton paper. Loan from the artist.

The luminous centre. There is no inner path without an outer perimeter. The path connects the practical and public dimension of life (the outer perimeter) to the mystical knowledge of divine reality (the luminous and ineffable centre).

Credits

Guest Curator

Fabrizio Boscaglia – Universidade Lusófona

Coordination

Jessica Hallett – Jessica Hallett (senior curator, Middle East, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum)

Diana Pereira – Diana Pereira (Cultural Mediation, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum)

Collaboration

Baltazar Molina, Elísio Vaz Gala, Margarida Ferra, Marta Guerreiro, Mia Gourvitch, Raquel Feliciano, Renata Fontanillas, Sara Campino, Sara Domingos, Xavier Ovídio, Yasir Daud.

Special thanks to Mussa Fuad (Fundação Islâmica de Palmela), Omid Bahrami and Professor Andrew Peacock (St. Andrew’s University).

Participatory process

Power of the Word is a participatory curatorial project that invites participants to investigate the Middle Eastern collection, together with the curatorial and mediation teams of the Museum and invited researchers.

The exhibition Divine Wisdom: The Sufi Way continues previous editions of the project dedicated to Pilgrimage (2019), Fables (2020) and Women (2021).

This fourth version took as its point of departure the spiritual dimensions of art, as well as of Sufi poetry. The working group was challenged to consider and debate the connections between works of art and recurring themes in Sufism.

The exhibition resulting from this collaborative process offers a reading of selected works, based on keywords of Sufism as well as ideas and images from universal spirituality.

The presential workshops involved moments of reflection and creativity, with the recitation of poems, some Sufi meditation (dhikr) accompanied by the sound of the douf drum, and the lively exchange of opinions on how to strengthen the curatorial concept as a path or way.

The participants represented a diverse group, with varied experiences and interests. Among them were people from the fields of academic research, education, fine arts, literature, music and museum practice. Some are Muslims and practicing Sufis, while others wanted to learn more about Sufism and participatory curation. Everyone engaged enthusiastically to enrich, transform, and challenge the life and cultural mission of the Museum.