What values count in decision-making about the sea?

It’s a key question for many working today to improve how we manage and protect the marine environment. Understanding societal value of the sea lies at the heart of the UK Government’s Marine Pioneer Programme (MPP), which is testing ‘natural capital’ approaches to marine and coastal management. It is also central to our Valuing the Ocean strand here at the Gulbenkian Foundation’s UK Branch, and to the work of the Marine Conservation Society (MCS).

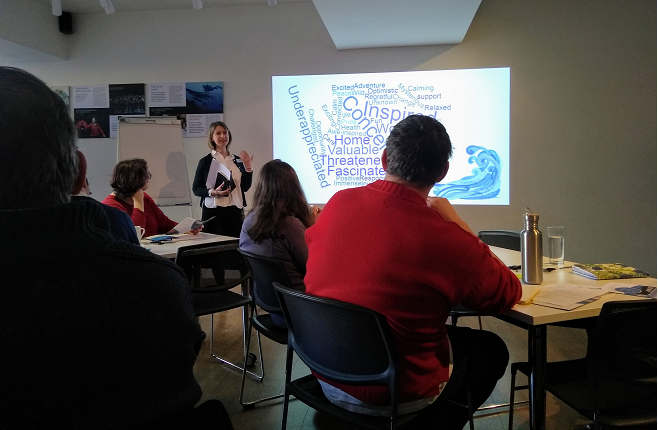

So, recently, in collaboration with the MPP and MCS, we hosted a roundtable of some 30 experts – marine social scientists, practitioners and policy-makers – to explore the many ways in which people value the ocean. The idea of the meeting was to understand, map and share the state of knowledge, and to discuss ways we might work together to move things forward.

Often only a narrow range of values shapes decisions about the sea. But if decisions better reflected the full range of societal value, perhaps better decisions would be made – decisions that are better supported and understood, more equitable, and lead to more sustainable management for the long term.

“Often only a narrow range of values shapes decisions about the sea”

On the day the group discussed some of the challenges to making this happen and some solutions.

Getting the language right

Jargon is a problem if we want a wider range of values to count. Jargon puts people off. They disengage because they don’t understand the buzzwords, and because they are not taken seriously unless they are using them. Even for the experts, specific terms can mean different things to different people; take, for instance, the many interpretations of a ‘natural capital approach’ (NCA).

The Marine Social Sciences Network is currently developing a glossary of definitions for the sector, which should help to address the issue. However, a deeper concern was raised: that the assumptions embedded in terms like ‘natural capital’ may reinforce economic value as a priority above all else.

Can we, should we question the fundamental terms of the discourse?

The natural capital approach should encompass the breadth of things people care about the ocean – from the beauty of a sea view to the biodiversity of marine life and the prosperity of the industries that depend on it. In practice, there’s a risk it becomes a shorthand term for ‘finding ways to pay for nature’ or prioritising the immediate economic value of resources over wider considerations for the long term.

“The natural capital approach should encompass the breadth of things people care about the ocean”

Making wider benefits count

But it’s still a challenge for government to incorporate wider values into decision-making processes, partly because the parameters for decision-making are often economic, partly because it is difficult to account for other benefits in ways that seem ‘robust’, and partly because other benefits are often taken for granted and so get overlooked.

At the beginning of the day, MCS previewed Our Blue Heart, a new documentary which clearly shows the breadth of things people in the UK value about the sea and the complexity of the trade-offs. For example, communities want the prosperity but not the impacts that coastal tourism can bring; impacts like the demand for holiday homes inflating the cost of housing for local people or the degradation of the marine and coastal environment.

Our Blue Heart builds on MCS’s Common Ground work, which has used the Community Voice Method (CVM) to make visible the diversity and nuance of people’s views and the benefits they share. Understanding what – or whose – values hold sway in decisions about the marine environment is fundamental if we recognise that societal benefits of the sea are held in common and effective decision-making must be underpinned by principles of social justice. Engagement processes like CVM can facilitate a transparent and participative conversation about how the environment is managed and the trade-offs involved.

Understanding the power relationships

Influencing decisions with a wider set of values is difficult if it’s not clear how decisions are made or who is making them. WWF-UK is trying to map the process and who holds the power in decision-making for the marine environment in North Devon as part of the Marine Pioneer Programme. But it’s not straightforward, even locally, as individuals have different levels of involvement and there are many groups. How might we improve transparency at all levels of decision-making so that more people can get involved?

Looking forward, let’s look back

Threaded through discussions on the day was a wariness of ‘reinventing the wheel’. One of the benefits of collaboration is more collective knowledge of what is already going on and what works. But what time or resource is given to reflecting on the outcomes of past decisions to inform the present? Or on the effectiveness of the process and the assumptions that underpin it, like who bears the cost, who benefits? Too often past mistakes are repeated as the political machine latches on to ‘new’ initiatives, and money and focus follow. How can we embed a reflective approach, and the resource needed to sustain it, in decision-making for the future?

Next steps

We are great believers in progress through collaboration! If you’re interested in these questions and staying in touch, please register through this short survey, which sets out the areas of enquiry and ideas that emerged on the day and asks if/how you might like to get involved.

We have also compiled a bibliography of works recommended by the roundtable participants.