The Emperor’s Flowers. From the Bulb to the Carpet

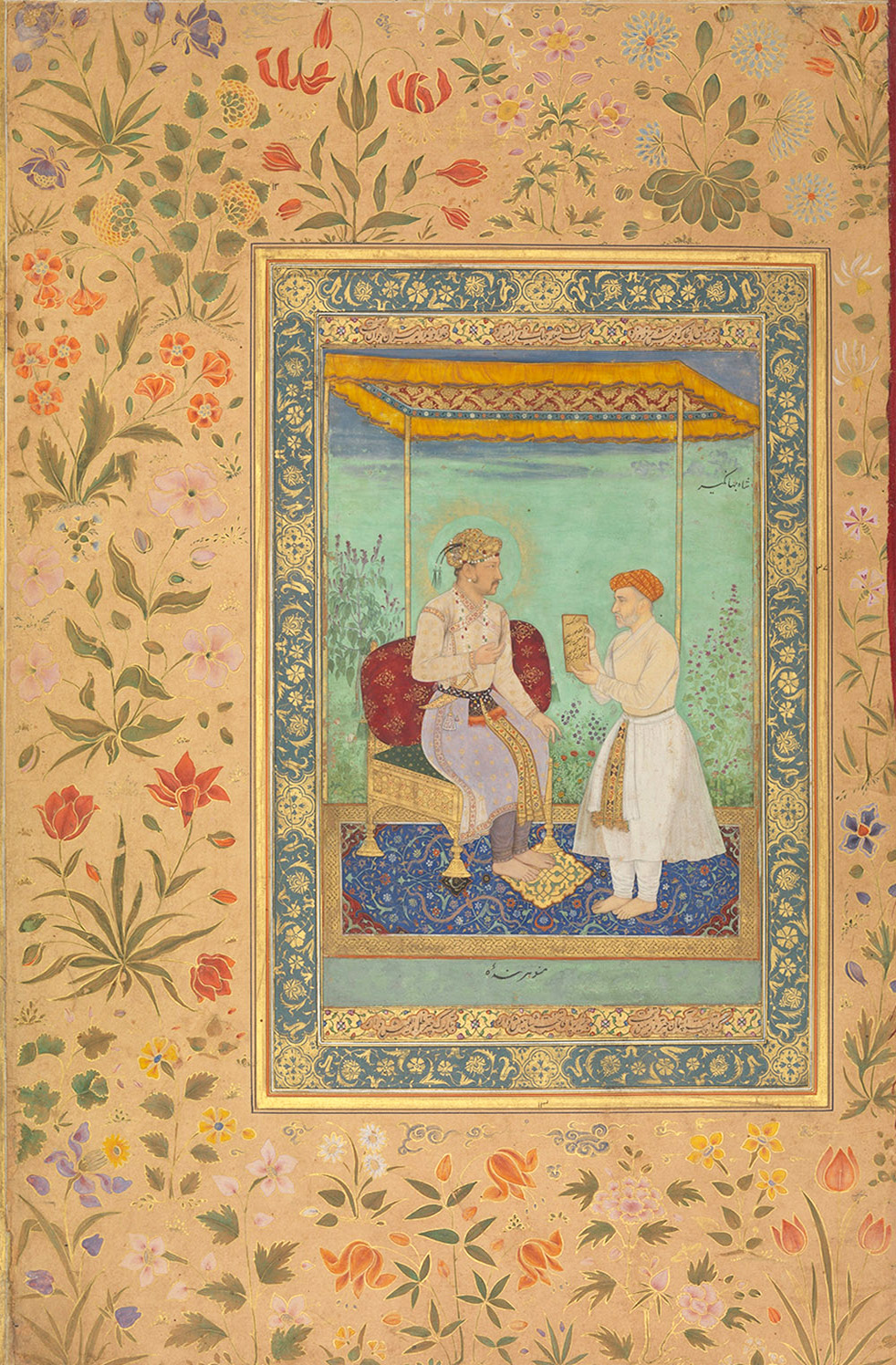

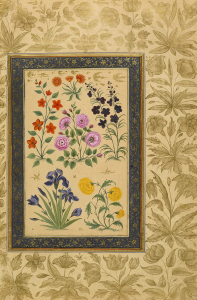

During the 16th century, the new relationships established by Europeans with the rest of the world reshaped their knowledge of nature. New products and plant and animal species which had never been seen before arrived from the Indies. From the Levant, exotic flower seeds and bulbs made their way into Europe. The greatly admired beauty of these flowers led to increasing attention from scholars. In great demand and admired by enthusiasts, scholars and aristocrats alike, flowers earned a special place in the botanical gardens created at that time, although only the gardens of the most fortunate contained specimens of these rare, highly sought after exotic plants. Cultivated by dedicated gardeners and described by botanists, flowers were painted and represented in lavishly illustrated albums. These publications were widely distributed throughout Europe and the extensive imperial regions across which Europeans journeyed. They were taken on diplomatic, religious and trade missions by European travellers and emissaries, and arrived at the Mughal court by the late 16th century. Under imperial patronage, local artists adopted the drawing techniques and models of representation found in these European books, by which a new decorative grammar emerged in the East.

This exhibition presents an analysis of the decorative motifs on two carpets in the Islamic Art Collection of the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum – Founder’s Collection produced in Mughal India during the reign of Shah Jahan (1627-1658). The type and naturalistic quality of the floral designs in these pieces evokes the dialogues established between East and West throughout the 17th century and the global circulation of people, books, images and botanical specimens of the era.

Know more

Flowers from the Indies, Europe and the Levant

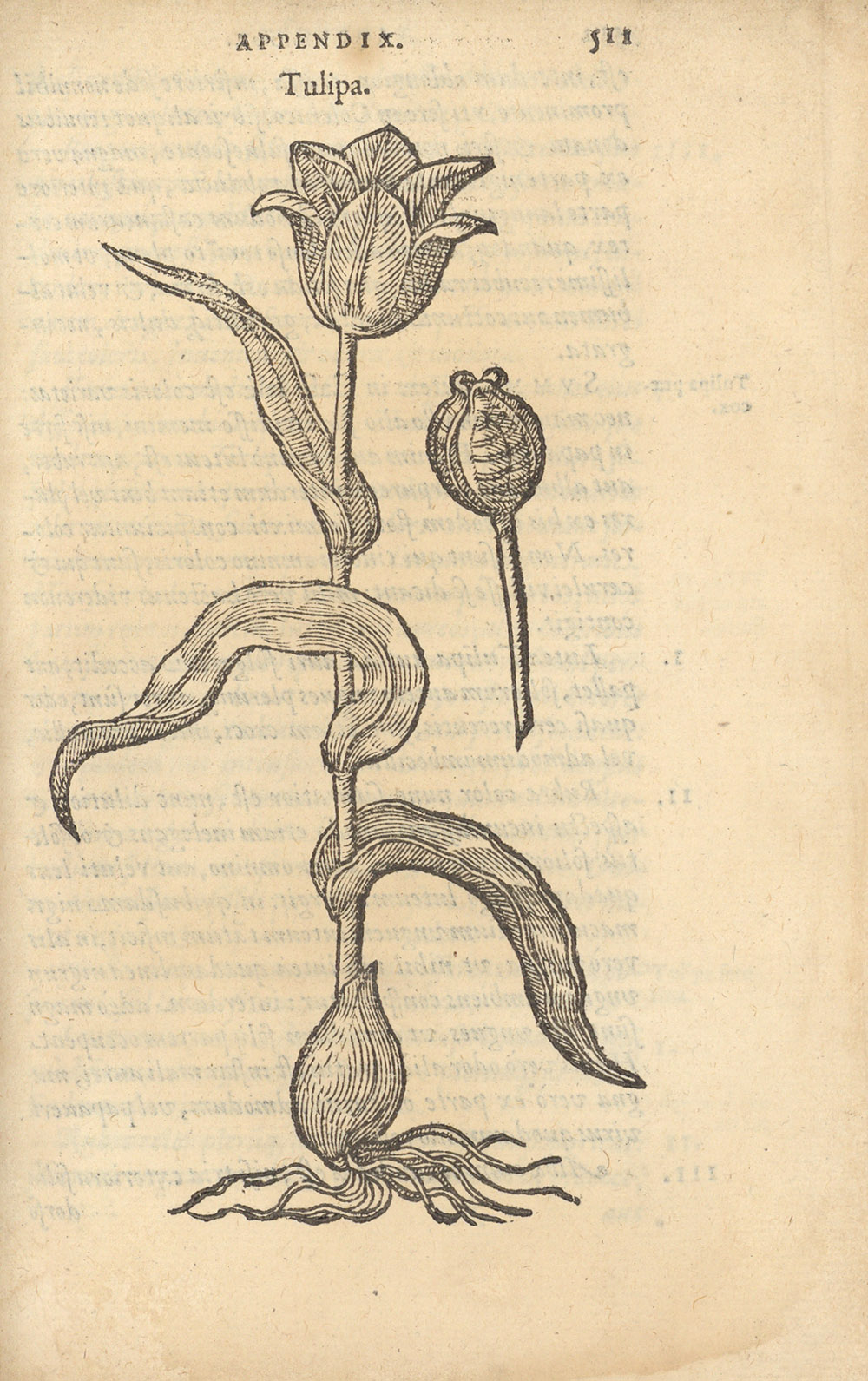

Upon encountering the diverse, exuberant natural life of the new lands they visited, the Europeans were filled with surprise and wonder. From the Americas and Asia came specimens of fauna and flora which had never been seen before. Meanwhile, eyewitness accounts of splendid gardens arrived from the Levant. Traders, travellers and diplomats who journeyed through the region commented on the beauty and diversity of its flowers. Propagated by bulbs, tulips, hyacinths, irises, narcissi, crocuses and fritillaries arrived in the gardens of Vienna in the diplomatic luggage of Ogier de Busbecq, the ambassador of Emperor Maximilian II (r. 1564-1576) in the Ottoman Empire. Clusius, charged with establishing the imperial garden in Vienna, dedicated himself to the study and description of these exotic flowers. At the heart of a wide-ranging network through which information and plant material circulated, bringing together scholars, enthusiasts, aristocrats and governors, the botanist described and dispersed these rare flowers across gardens all over Europe.

Flowers to Describe and Admire

At the beginning of the 17th century, growing fascination for the creation of gardens and collection of rarities began to emerge. This led to a keen search for information on rare specimens and an exchange of plant seedlings between botanists, scholars and enthusiasts. Significant movement of plant material allowed the dispersal of local and exotic flowers around Europe. Taking advantage of the frequent passage through European ports of travellers and missionaries bearing specimens from the Americas and Asia, large collections of exotic plants were created. The most lavish gardens attracted visitors to wonder at the collections of newly arrived flowers. This enthusiasm for the study and cultivation of flowers was accompanied by intensive production of botanical compendiums, anthologies, catalogues, prints and floral albums, which were widely circulated.

Circulation of Images between Europe and the Mughal Empire

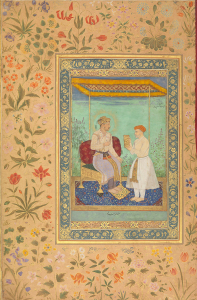

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, various European diplomatic, religious and commercial missions sought closer relationships with the Mughal Empire. Besides the Society of Jesus missionaries who were welcomed from 1580 by Akbar (r. 1556-1605), other European travellers and diplomats also reached the Mughal Empire. They encountered a sophisticated court which was open to dialogue with other cultures. Recognising the relevance of Christian iconography as an instrument of missionary work, the Jesuits took paintings, prints and illustrated publications with them on their mission. Due to their prolonged presence in the imperial court, the large number of illustrated works they brought from Europe and the constant support they gave local artists in the production of their works, the Jesuit missionaries had an extensive influence on the works of art produced in the region. Impressed by the naturalistic representation of flowers and animals displayed in many European albums, the court artists developed new ways of representing nature.

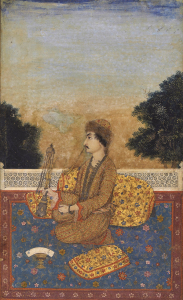

The Emperor’s Flowers

The Mughal Empire was founded in 1526 by Babur, a Turco-Mongol prince from a small kingdom in Central Asia. The Mughal dynasty governed India for almost three centuries, during which there were three notable emperors: Akbar, Jahangir and Jahan, who became known for the refinement of their culture and tastes, and their significant patronage of the arts. It was a period of opening up to the outside world, which was reflected in an artistic production attaining unprecedented sophistication. It is believed that the first imperial carpet making workshops were established during the reign of Akbar. Persian carpet makers were called upon to teach local artisans. It is not surprising then that the first Mughal carpets displayed a strong Persian influence, which would be maintained. However, during the reign of Jahan, unique decorative motifs began to be developed, resulting in a highly characteristic type of floral decoration known as ‘Indian’, most likely inspired by the illustrations conveyed by the European botanical prints and albums which reached the Mughal court in the 16th century.