René Lalique room

Following a period of renovations, the room exclusively dedicated to René Lalique’s jewellery and glassware at the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum has now reopened to the public. Explore the new gallery with a selection of videos, texts and images showcasing some of the pieces on display, and specially designed sections highlighting the main themes in the artist’s work.

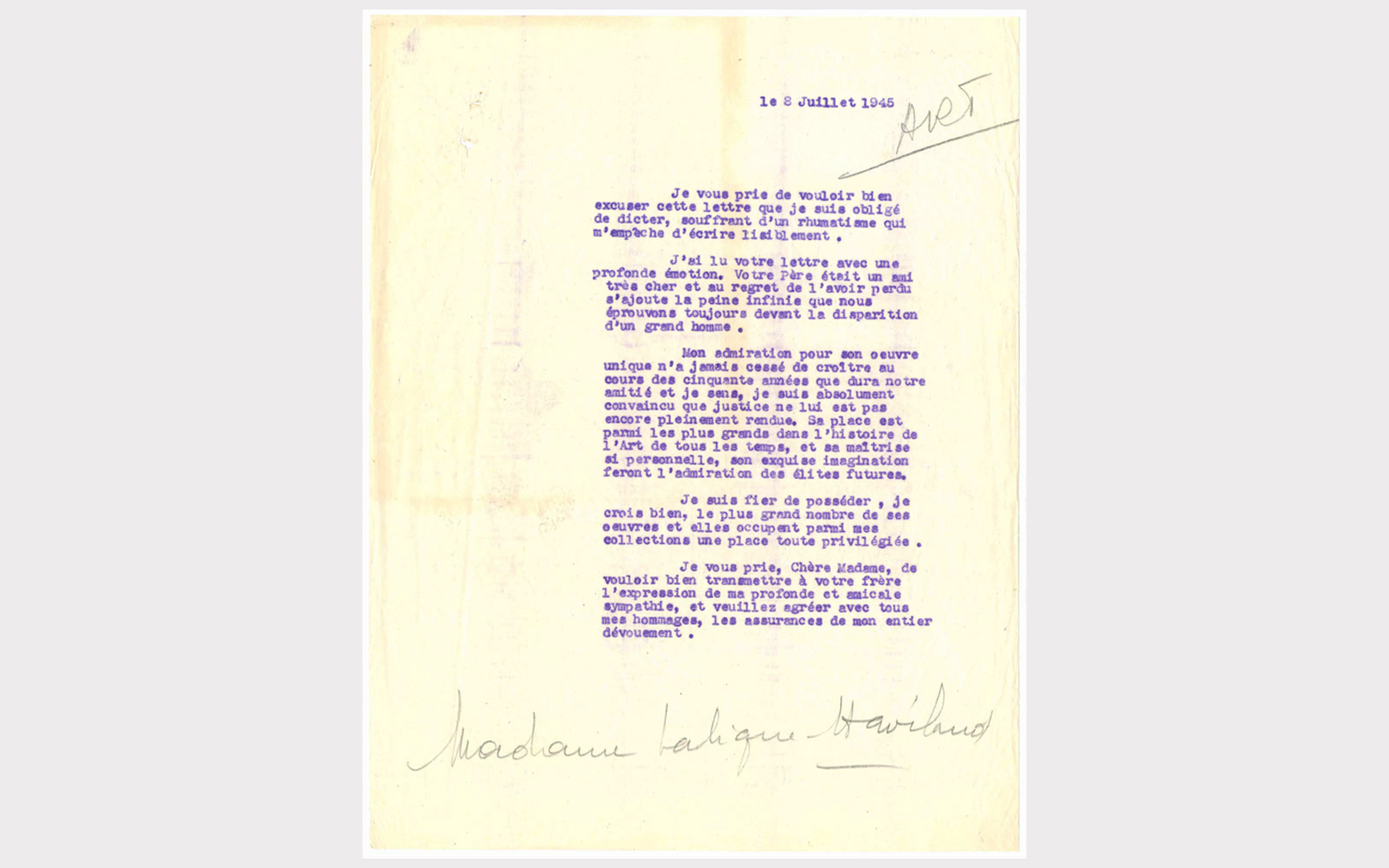

René Lalique and Calouste Gulbenkian

René Lalique (1860-1945) and Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian (1869-1955) met in the mid-1890s. In a letter to Suzanne Lalique-Haviland (1892-1989) following the artist’s death in 1945, Calouste Gulbenkian expressed his deep sorrow to the Lalique’s daughter at the loss of his friend: ‘Your father was a very dear friend, and my regret at his loss is deepened by the infinite sorrow one always feels upon the demise of a great man. My admiration for his unique work grew and grew over the course of our fifty-year friendship […] I am proud to have in my possession what I believe to be the largest existing set of his works, and the latter occupy a privileged place in my collections.’1.

The collection of almost two hundred pieces purchased by Calouste Gulbenkian directly from René Lalique, between 1899 and 1927, reveals the artist’s prodigious imagination and the collector’s tastes and personality. It provides an overview of Lalique’s work, with a particular focus on the Art Nouveau period when Gulbenkian acquired several of the brilliant creator’s most famous jewels.

Ideal and Metamorphoses

The image of the woman, explored exhaustively in the art of this period, was a central motif in Lalique’s work and provided a pretext for some of his most daring creations. Purchased by Gulbenkian in 1903, the Dragonfly-woman corsage ornament probably worn on stage by Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923) has hinged wings in opalescent enamel, lending it a dramatic dimension. The jewel combines two of the recurring themes in Lalique’s imagery: the female figure and the insect into which she transforms to create a hybrid creature, a woman-insect.

Lalique’s huge repertoire was enriched by themes inspired by exuberant fauna, either real or imaginary, evoking a fabulous bestiary influenced by the eclecticism of the time. This source of inspiration, comprising reptiles and insects that both attract and repel, gave rise to some of his most famous creations. The Serpents corsage ornament, purchased in 1908, is made from gold and opalescent enamel, a technique which was omnipresent in Lalique’s jewellery, and is a variation on a piece presented by the artist at the 1900 Exposition Universelle.

The Classical Inspiration

In 1902, Lalique moved to 40, Cours-la-Reine in Paris. The Female figure centrepiece was among the objects the artist displayed at his home and store, where Calouste Gulbenkian purchased it in 1905 for the highest price he ever paid for a work by Lalique. Like The Capture of Dejanira inkwell tray, this piece includes decorative elements made from glass, which Lalique incorporated into his jewellery and silverwork from an early stage in his career.

At the turn of the century, Lalique frequently employed lost-wax casting, a technique derived from an ancient process for casting objects in bronze, which he adapted to his more elaborate glass creations. The Gorgons vase in moulded-blown glass, purchased around 1913, is decorated with gorgons’ heads and is part of this group of unique objects. A later piece, the 1925 Cluny vase from the artist’s Art Deco period, is decorated with masks inspired by classical theatre and uses the moulded-pressed glass technique.

The 1900 Exposition Universelle

The Figures and serpents brooch, made from ivory, echoes the ancient Roman sculpture Laocoön and his sons (Vatican Museums) and is one of the four jewels in the Gulbenkian Collection to have appeared in Lalique’s hugely successful display at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. The use of unexpected materials rather than precious stones to make jewellery, such as ivory, enamel, horn and glass, is indicative of Lalique’s decisive role in transforming the art of jewellery, which he truly revolutionised with his original creations. The artist’s capacity for innovation is visible in the medieval and Renaissance-inspired themes in various pendants in the collection.

In his silverwork, Lalique also combined materials such as glass and silver in a single object. The Thistles vase, which was also shown at the 1900 Exposition Universelle, and the Serpents sugar bowl in blown and patinated glass held within a hollow silver structure of intertwined snakes, a recurring theme in Lalique’s work, are representative of this merging of materials.

The Invention of Modern Jewellery

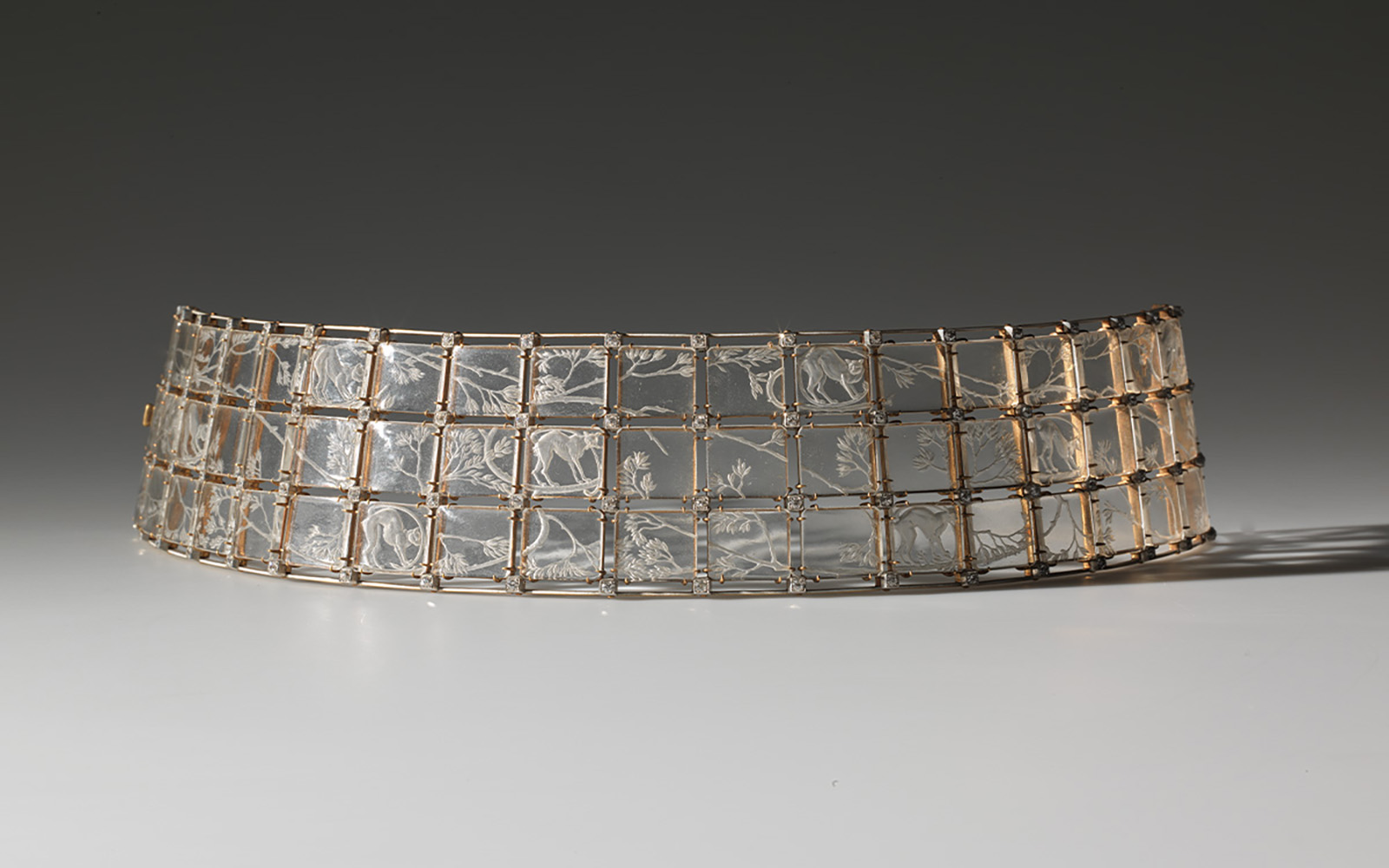

In 1897, Émile Gallé (1846-1904) described Lalique’s submission to the Paris Salon as the definitive creation of ‘modern jewellery’. The artist’s intention to produce ‘something never seen before’, as he confided to jeweller Henri Vever (1854-1942) two years earlier, was thus achieved. The Wooded landscape choker plaque was the first of eighty-two jewels in the collection to be purchased directly from the artist, with one exception: The offering brooch t. The capture of Dejanira pendant, where sculpture and handcrafted enamel meet, confirms the concept of the ‘complete work of art’.

René Lalique participated in the 1900 Exposition Universelle with around one hundred pieces exhibited in spectacular display cases designed specifically for this purpose. The Dragonfly-woman corsage ornament, the Cockerel diadem and the Wooded Landscape choker plaque were also among the jewels that drew surprise and admiration from visitors to the exhibition.

Exuberant Fauna

The Peacock corsage ornament was purchased by Calouste Gulbenkian in 1900 and depicts a bird emblematic of the Art Nouveau period, in blue and green enamel, one of Lalique’s preferred materials, punctuated by cabochon opals. Iridescent opal is present in a large number of jewels in the collection and was the jeweller’s favourite stone. The poet Robert de Montesquiou (1855-1921) dedicated a verse to the artist in his compilation Les Paons (1901), whose cover was illustrated by Lalique himself.

The theme of the woman-flower that was so prominent in the poetry of the period had a significant influence on Lalique’s creative work. The Female Face pendant features a hanging baroque pearl of Renaissance influence which is surrounded by four open poppies in patinated silver, an emblematic flower of Art Nouveau associated with the dream world. The opalescent enamel Orchid pendant, symbolising purity and fertility, embodies the motif of the eternal encounter between woman and flower and the metamorphosis arising from it.

Omnipresent Nature

The collection includes a variety of diadems and combs made from horn, an innovative material used by Lalique in his jewellery, presented for the first time at the 1896 Salon, in Paris. In the Orchids diadem, horn and ivory are combined to create a sublime synthesis of nature, with Lalique recreating the natural world as if moulded directly from life. Orchids are symbolic to the Art Nouveau period and take pride of place in the centre of the diadem.

Strongly influenced by the naturalism of Japanese art, which attracted many admirers across Europe during the second half of the nineteenth century, the elegant Apple tree bough diadem characterized by its decorative simplicity is one of the twenty-seven items made from horn in the collection and is another example of the wonderful, inexhaustible botanical repertoire that inspired so much of Lalique’s work throughout his career.

Glass:‘the wonderful material’

From early on in his career, the quest for transparency was a key concern for Lalique. The Cats choker made from rock crystal is an example of this search. After World War I, in 1922, Lalique opened a glassmaking factory in Wingen-sur-Moder. He abandoned jewellery making in 1912 and focused all his attention on his activities as a ‘creator-industrialist’, producing objects from moulded-pressed glass on a large scale. Commissions for architectural and decorative projects, with a clear idea of modernity, were also produced at his factory in Alsace.

In 1925, Lalique once more achieved public and critical acclaim at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, where he presented his new works in glass, which he described as a ‘wonderful material’. In this way, the artist created an answer to the aspirations of a new era of optimism and consumption, represented by the Art Deco style, and contributed to a major shift in the art of glassmaking.

Views from the René Lalique Room

Videos on René Lalique

See the videos that curator Luísa Sampaio produced for the temporary exhibition René Lalique and the Age of Glass.

Sponsor of the Renovation