Public space | private space

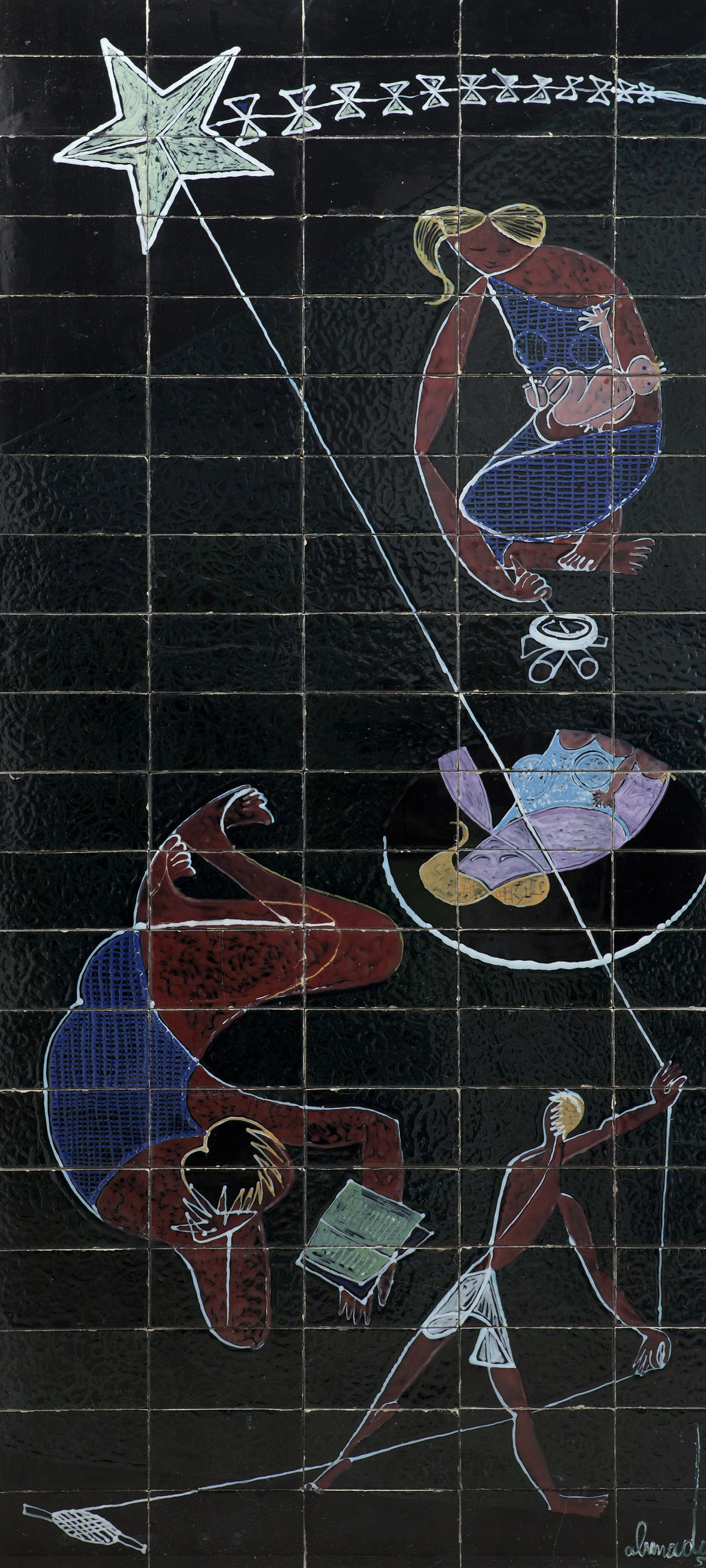

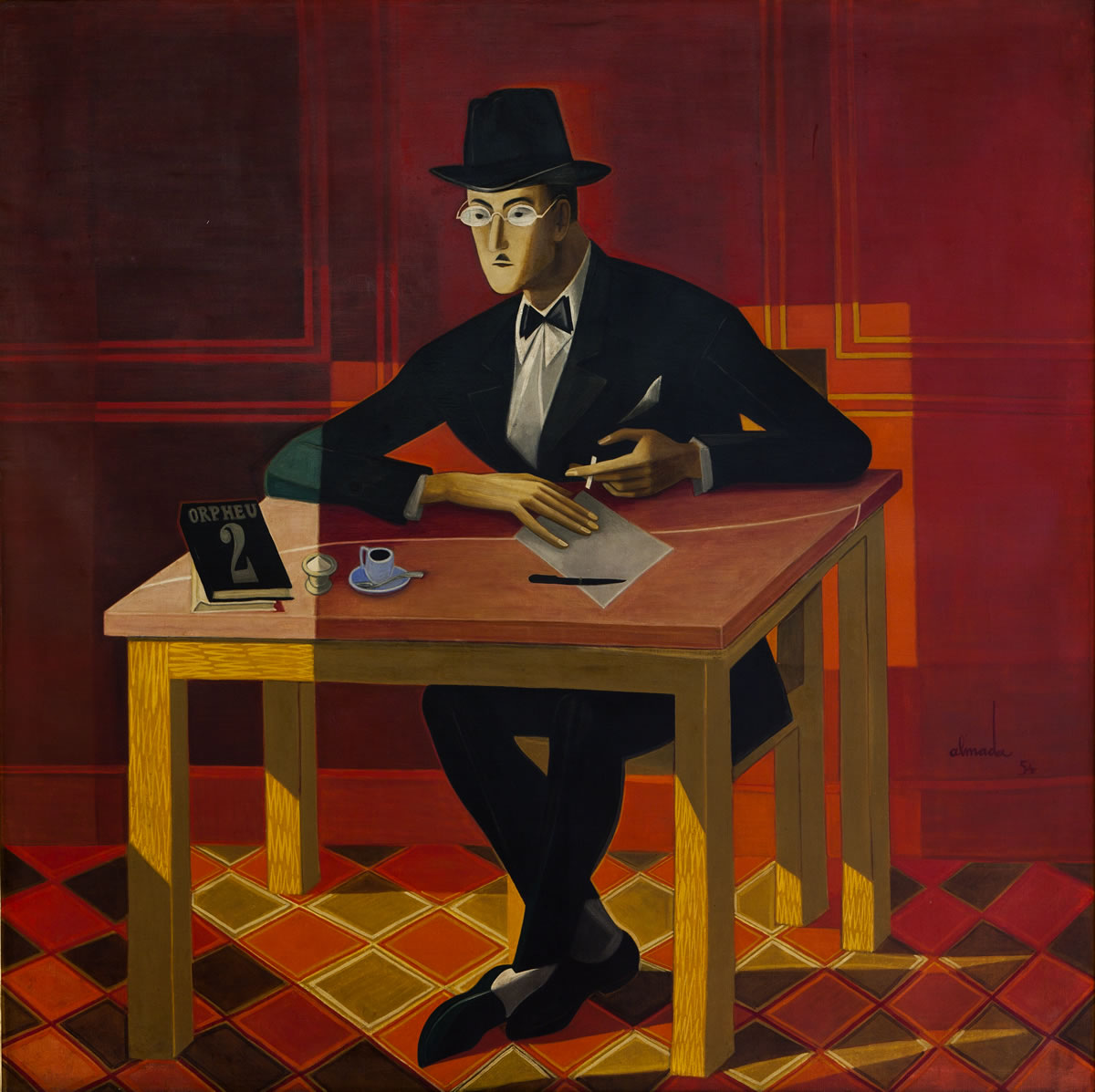

In the absence of art galleries, dealers or an art markets, Almada, as did many other artists, worked from early on in his career under commission from clients such as the tailors Alfaiataria Cunha, the café A Brasileira in Chiado, the Bristol Club, or the many newspapers, books, covers or posters that commissioned his drawings, illustrations and graphic works.

Upon returning from Madrid, in 1932, Almada witnessed the emergence of the programme of political propaganda of the Estado Novo, which had started to rely on modern artists and architects to establish its image, and had become nearly the only means of subsistence for the large majority of them. The integration of all arts, the recuperation of traditional craft and the convergence of high and applied art were all dictums of the modern period: in the Arts & Crafts movement, in art nouveau, in Noucentisme, in De Stijl or in Bauhaus. This modernist matrix was also present in authoritarian regimes, such as the Italian or the Portuguese, serving a propaganda that exploited the legitimation of change sparked by modernist discourse, to promote the renewal of a nationalistic image through public architecture and decoration.

Almada operated within an artistic milieu where artists often had to serve different and contradictory uses of modernity. However, both in testimony and in writing, he took issue with the arrogation of art by the State, repeatedly making the unconditional defence of artistic freedom. Generally speaking, the themes he was commissioned for were predefined, but we can also find examples of a certain deviation from this thematic control, to which Almada often responded with an either subtle or overt insubordinate humour.