Cinema, humour and graphic narrative

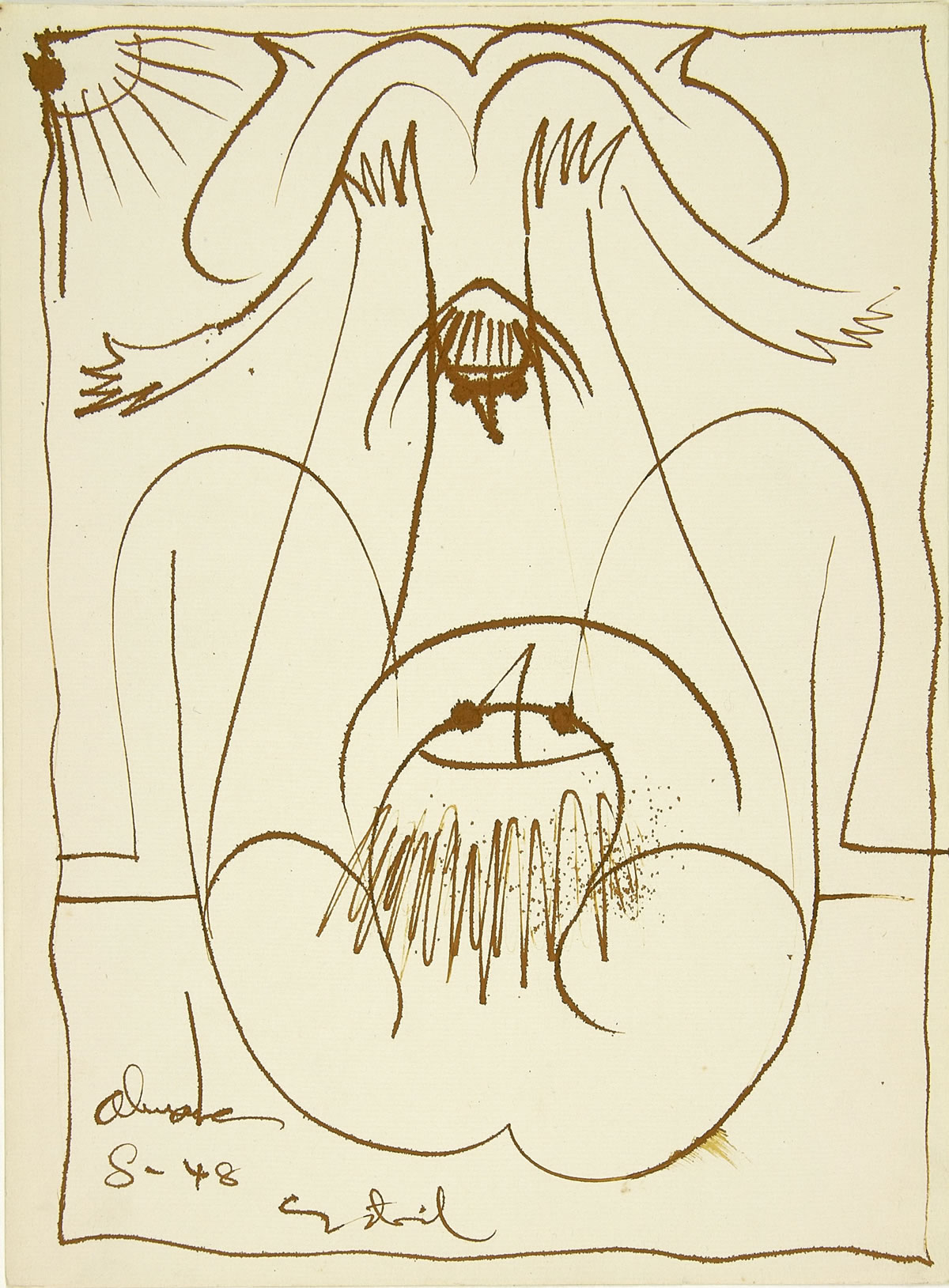

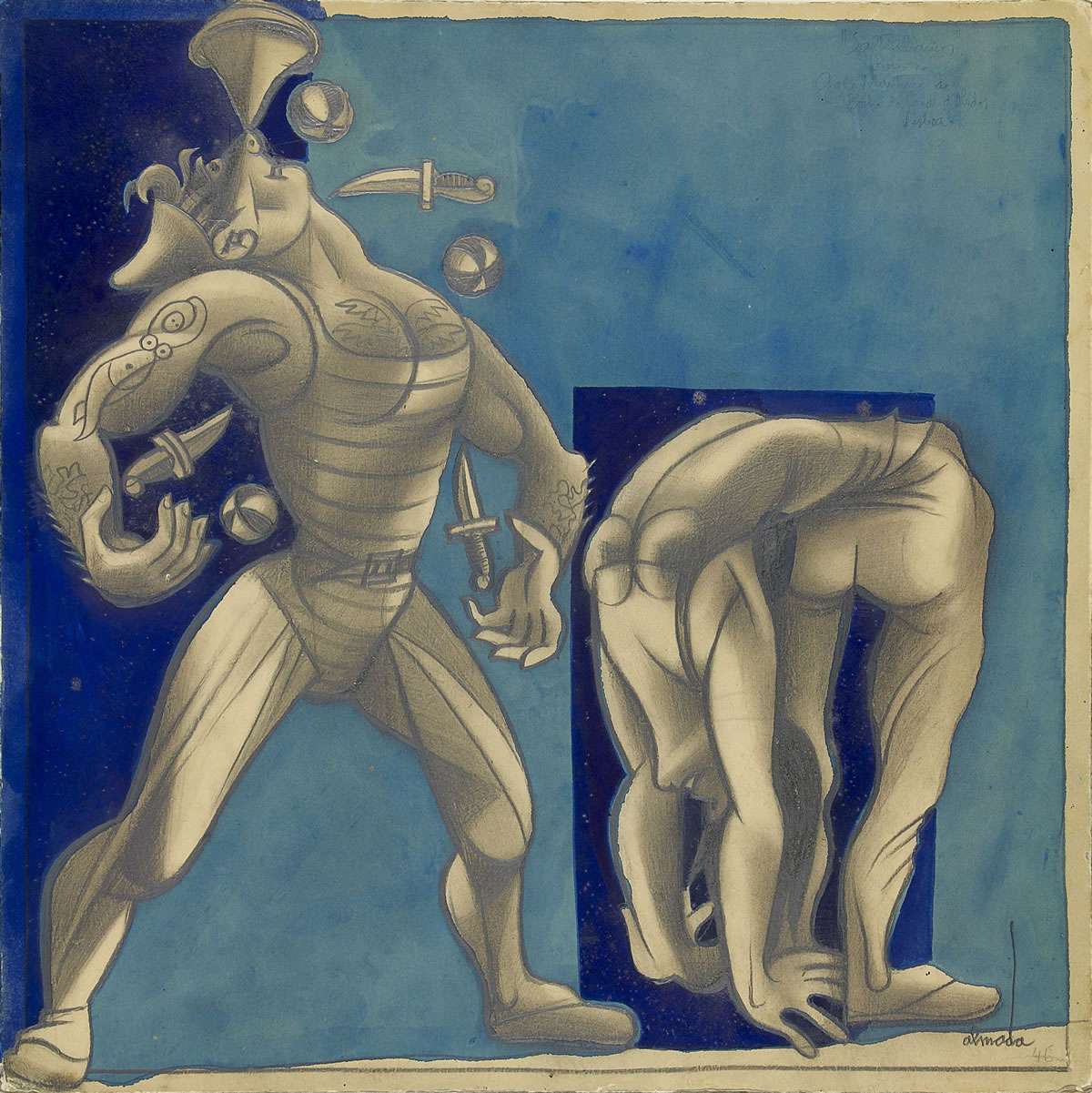

Almada Negreiros’s relationship with the cinema spans his entire life, both as spectator and artist. By 1921 he had already written an article revealing his admiration for Charlot, a character comparable to the saltimbanco [street acrobat] that Almada held so close to his heart. In that same year he was an actor in the film O Condenado [The Condemned], by Mário Huguin, and later he would recount: “In 1913 I tried to make an animated film with cards, a part of which I preserved for quite some time, but I eventually lost it. Later, during the period of the avant-garde, I planned with the painter Francisco de Cossio several amateur experimental films, which we never managed to direct.” (1959).

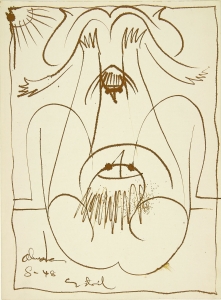

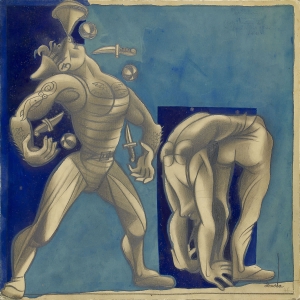

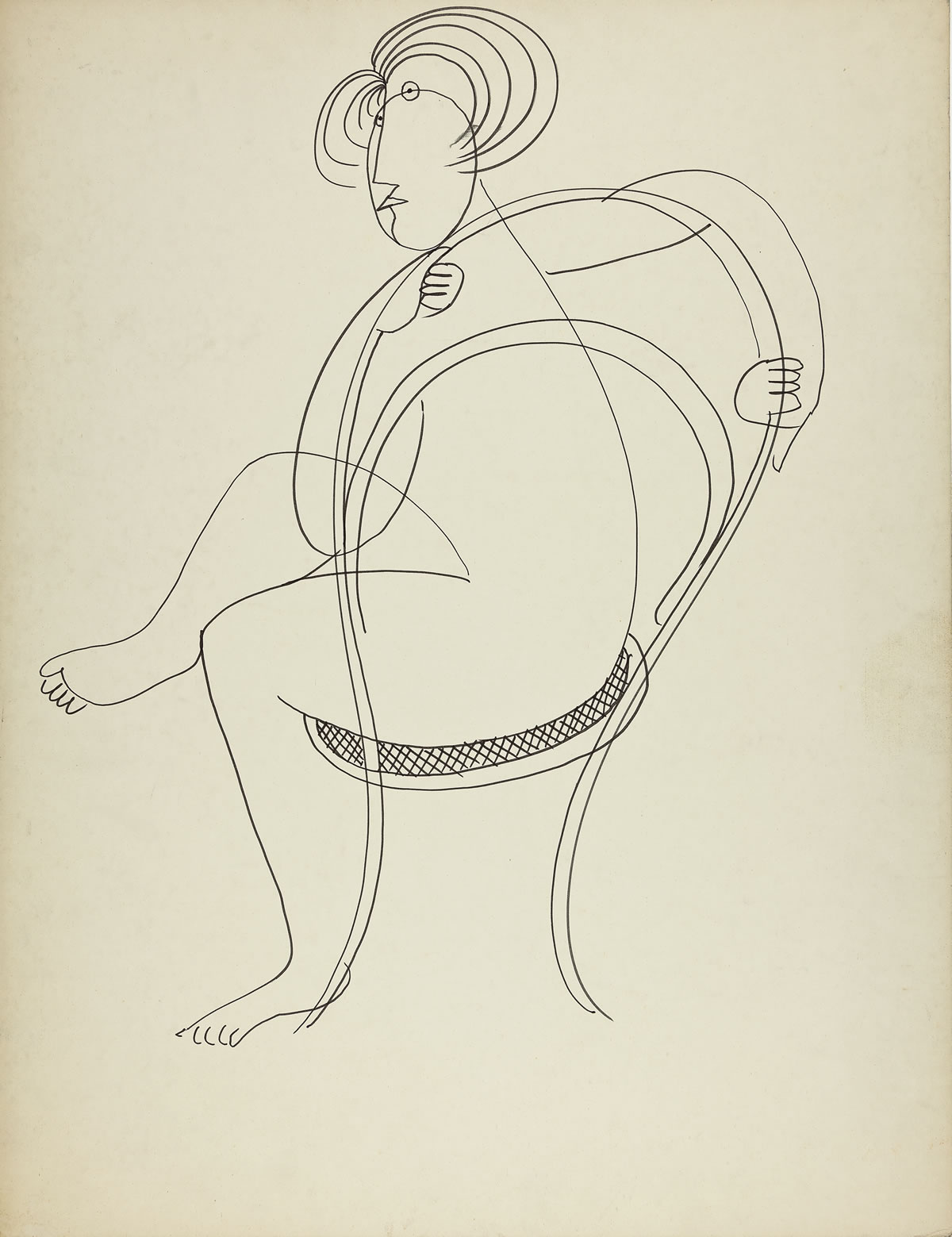

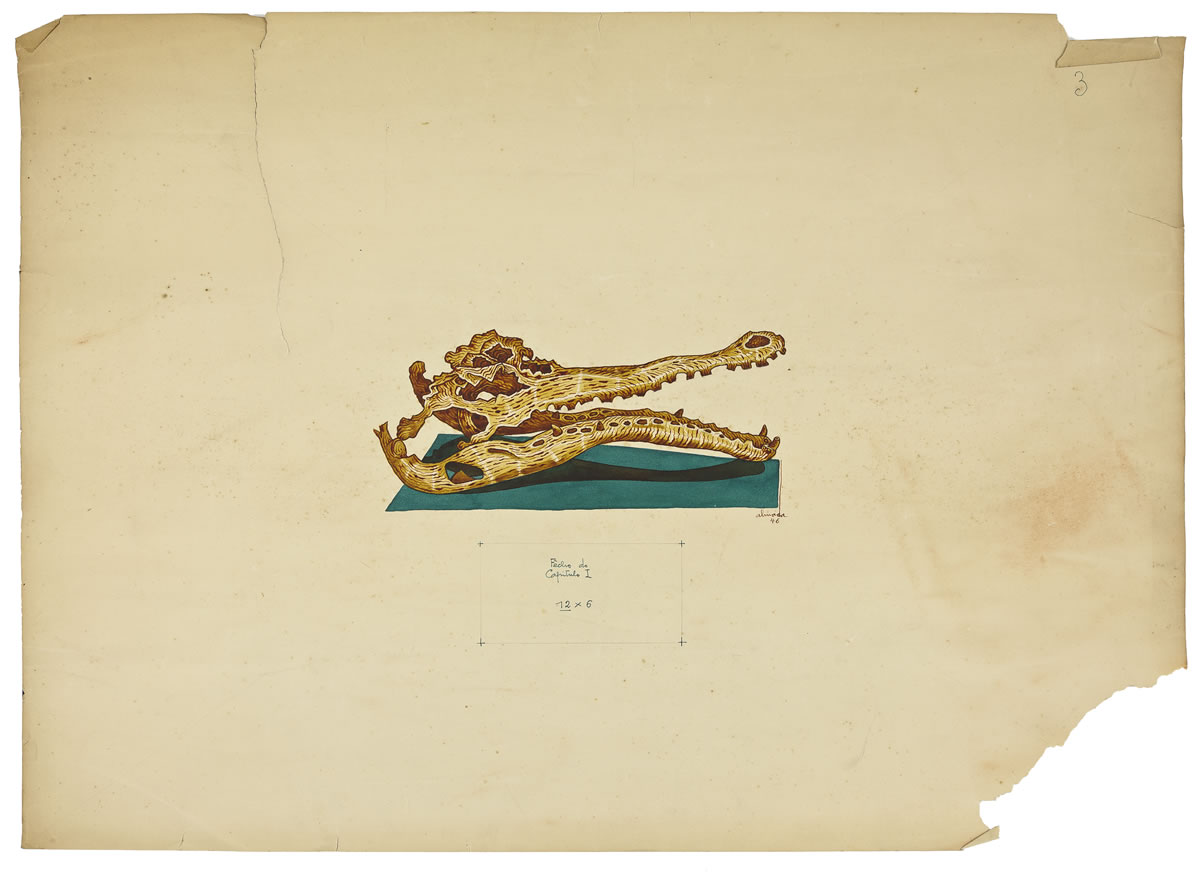

Almada worked in the publicity department of Paramount Pictures, designing plaquettes and posters, and in Madrid he made bas-reliefs for the refurbishment of the Cine San Carlos, depicting scenes from various film genres, constructed so that they replicated standard film frames and shots. He also exalted animated film in a conference given on the occasion of the premiere of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in Lisbon (1938), rating it as the moment of true autonomy of the cinematic form, thence unencumbered by the need to reproduce the real. The magic lanterns he designed in 1929 and 1934, along with several complementary series of drawings, also bear a strong affinity with animation, where Almada saw the prospect of drawing fulfilling its purpose by acquiring movement. For Almada, cinema could well have been the modern phase of the graphic narrative.

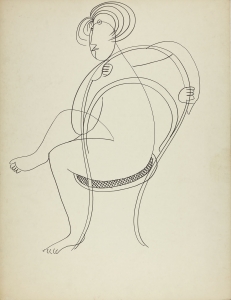

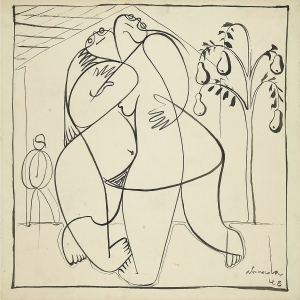

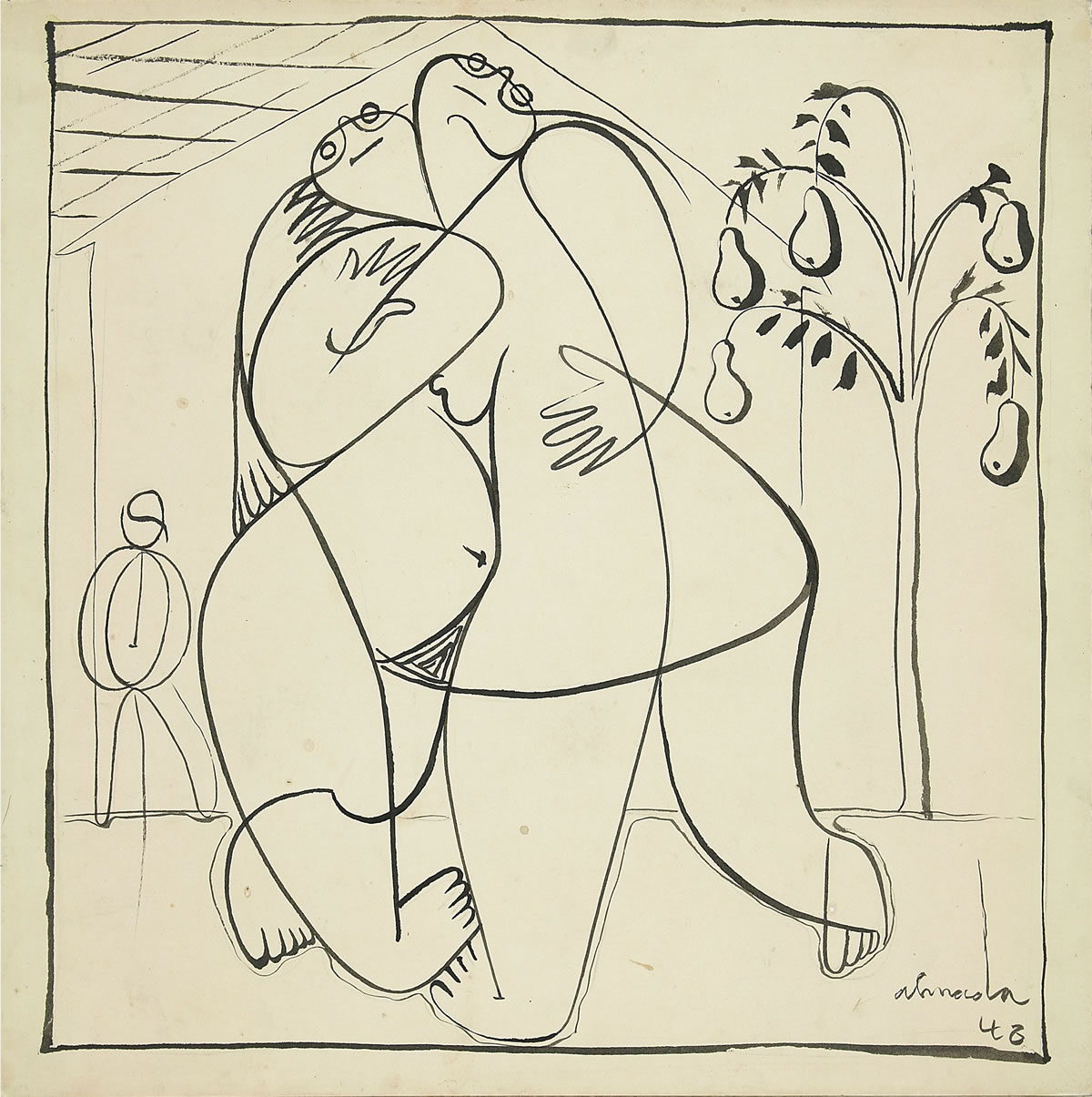

In 1969, in an interview on the popular TV show “Zip-Zip”, Almada highlighted the significance of humour, going as far as to state that it had propelled the passage from the 19th to the 20th century, with reference to the comic strip, and placing it at the very heart of the modern condition. Cartoons, graphic novels, illustration and graphic work were part and parcel of modernity, as was the printed page, at once image and text, which had become one of the main tools for artistic intervention. Contrary to other mediums, its potential for propagation and synthetic immediacy carried an incomparable efficiency. Besides, in a fundamental text for modernity, Baudelaire had already elected an illustrator as the “painter of modern life”.

One can see the forerunner to the graphic narrative and humour in fresco paintings, friezes and stained glass, but also in the stories the saltimbanchi [street acrobats] told with drawn images, as they moved from town to town. Such procedures remained throughout Almada’s artistic career as the means that could best accomplish what he regarded as the ultimate function of his art: communicating with the public.