Ana Hatherly and the Baroque. In a Garden Made of Ink

A visual artist, filmmaker, translator and writer, Ana Hatherly (Porto, 1929 — Lisbon, 2015) was also a Professor of Baroque Literature. Her research led to a greater appreciation of this historical period, revealing a deep affinity between the 20th-century experimentalists, of which she was one, and their 17th- and 18th‑century forerunners. This exhibition‑essay seeks to show this relationship of familiarity — although through a temporal inversion with a 17th- century flavour, as if in a world reversed. We not only show the influence of the Baroque on the artist’s work, but also how she influenced it, reinvented it, directing our attention from a superficial formalism, that defined the Baroque as excessive decorativism, towards the Baroque soul, towards its particular way of seeing and orientating itself in the world.

Ana Hatherly’s essays provided us with the thread that runs through this exhibition, the categories of the Baroque world view that are also present in the artist’s visual and poetic work: the Labyrinth and its folds upon folds; Time, and the resulting paradoxical focus on the Game and on Death; Allegory, and the joy of interpretation it fosters; Metamorphosis between painting and poetry, between drawing and writing. These are the constantly forking paths in this “garden made of ink”.

About the event

Tradition as innovation

The incorporation of the past into the present is a subversive action, because one of the most surprising effects of the action of time is the transformation of the usual into the strange, the known into the unknown, the ordinary into the exotic. The incorporation of older elements into a modern context disrupts continuity, disperses the noxious continuity that leads to habit, creating a conflict, a contrast, which cannot help but awaken our consciousness. All culture is dialogue and there is no dialogue without confrontation..

Ana Hatherly, A casa das musas, 1995

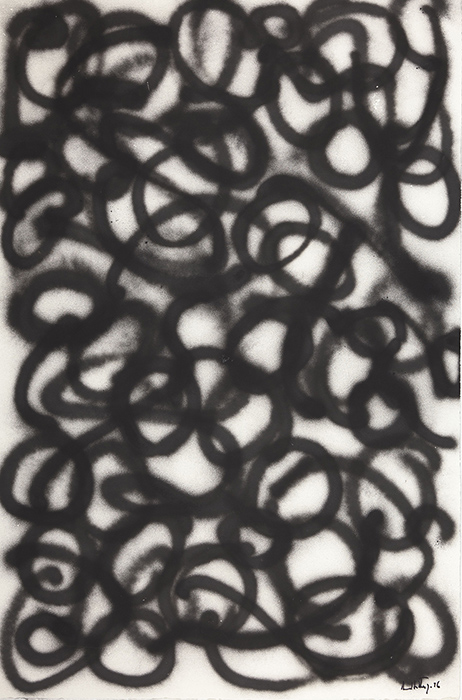

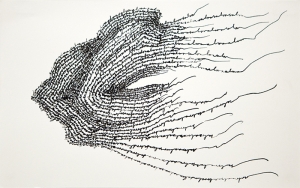

Labyrinth: folds upon folds

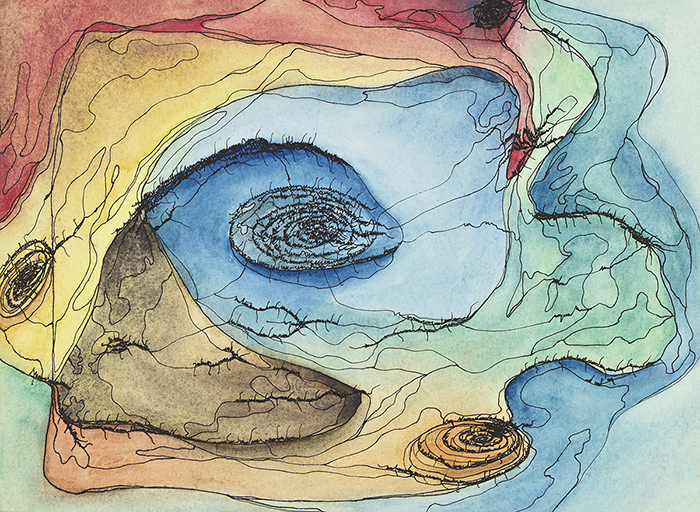

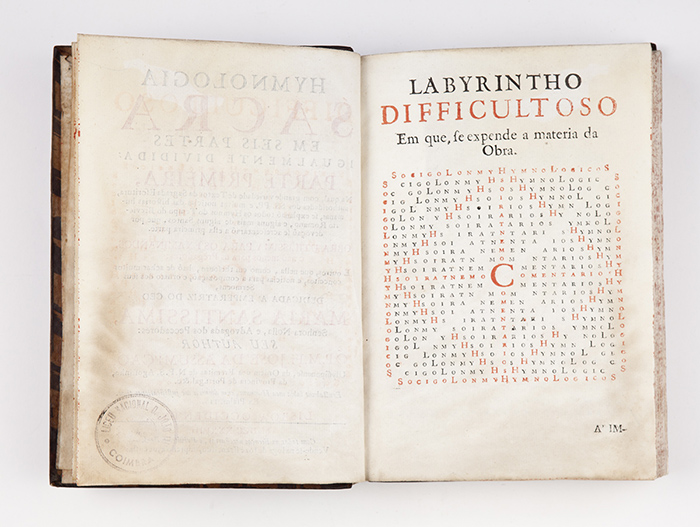

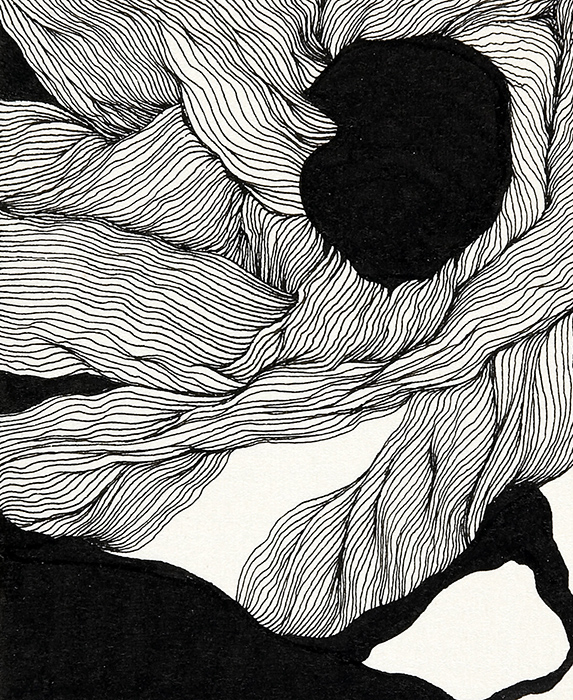

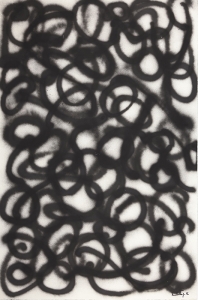

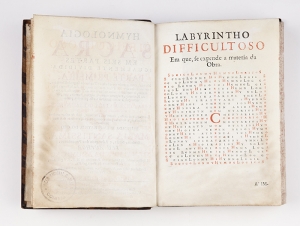

One of the recurrent categories of the Baroque is the Labyrinth: from the 17th-century garden, to the existential experience of getting lost, to the spiritual need to find one’s way in an ambiguous world. Recognising this, Ana Hatherly collected the forgotten “poetic labyrinths” of the 17th and 18th centuries, conducted an archaeology of the visual poetry of the 20th century and formed a library (another metaphor for the labyrinth) of “visual texts”, in which rules and invention and restrictions and freedom are counterbalanced. These places created by the word are not only a space on a page, but also a mental and cultural topography. The folds upon folds that give the labyrinth its multiplicity, like the draping of Baroque sculpture, are an image of a convulsion that is not only external but internal. The creation of series reveals this same restlessness: repeating and diverging, variations on an open form. Through this, in this instability, one can perceive the importance of mapping – another Baroque and “Hatherlyan” theme: in her drawings we encounter wandering lines, dead ends, dizzying spirals. They are maps from the imagination and from memory.

Time: the Game and Death

The true protagonist of Baroque art is Time. Out of this crucial confrontation with finitude, two categories emerge that are omnipresent in Baroque culture: the Game and Death. Baroque man wanders between an agonised and a ludic posture. What is also evident here is a taste for the paradoxical, and the overcoming of dichotomies: dark merges with light, sublime with grotesque, the religious with the profane, the comical with the serious. With no defined boundaries.

In Ana Hatherly’s work the ludic is also a fundamental critical category – the creation is a ludic act. As she wrote in the book O mestre, “the garden is a place for playing”, but it is also the place of the “death of the players”: the Baroque wavers between the fête galante and the vanitas – the deception of the world, the awareness that “everything passes” (Saint Teresa of Ávila), the assertion of destruction as a law of life and art. A lesson of darkness: the nocturnal is an interior landscape.

Allegory: the joy of interpretation

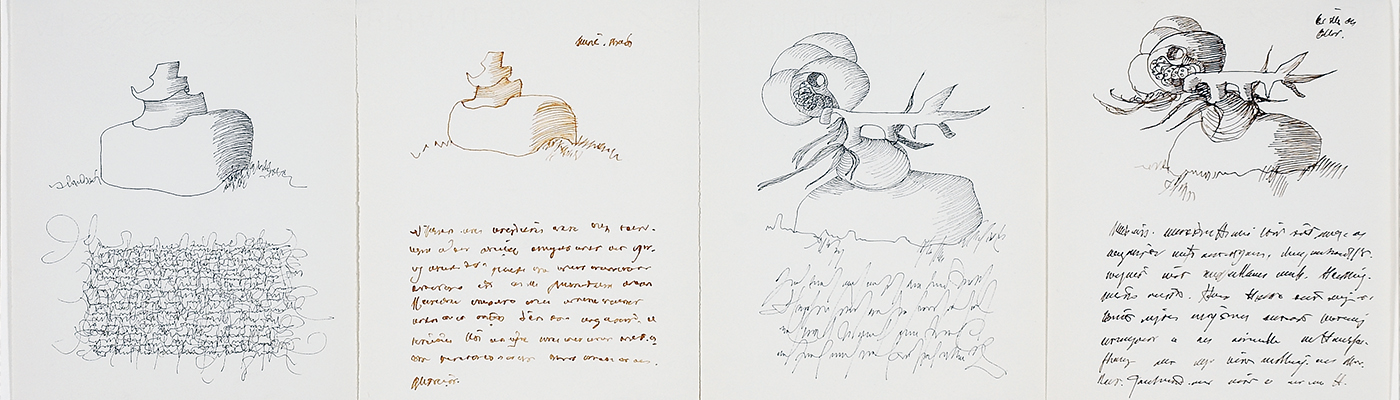

Allegory is one of the strategies of Baroque rhetoric: it provides a stairway from creature to creator, from the natural to the transcendent, from the material to the ideal. Everything is something else. The Baroque displays an interest in reality and an awareness of nature, yet it is not a naturalistic realism, but a symbolic, emblematic representation. It demands effort from the reader or viewer, who must be prepared and active, must know the code in order to interpret.

We find this hermeneutic requirement in Ana Hatherly’s interest in dreams, which she wrote down every day and asked friends to interpret. Or in her study of the symbology attributed to flowers and fruits, in order to understand works such as those of Josefa de Óbidos or Sóror Maria do Céu, and returned to in her art work: is a pomegranate just a pomegranate? The allegorical impulse spiritualises the tangible and sensualises the spiritual. In the Baroque, where vision reigns, the painter is a preacher.

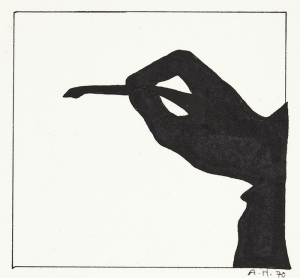

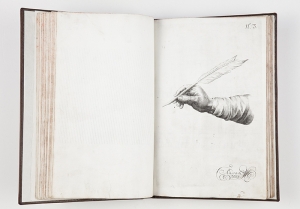

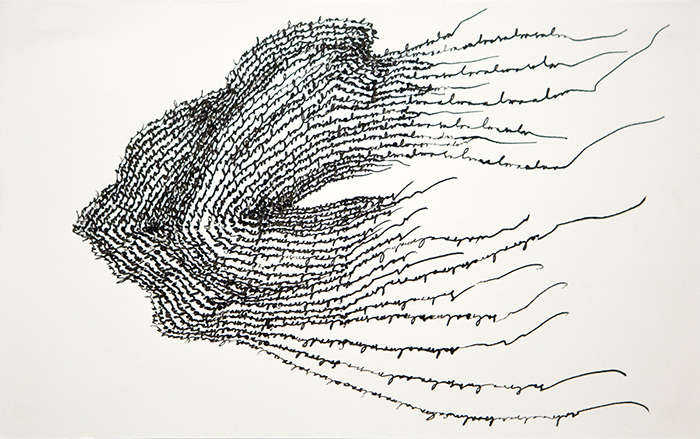

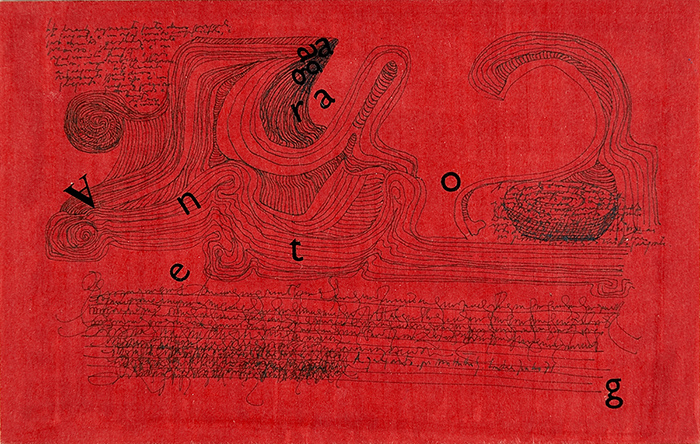

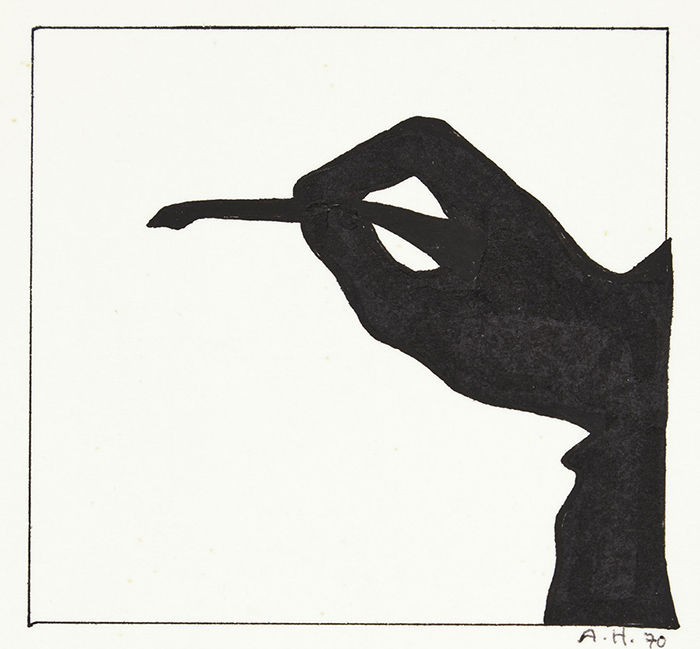

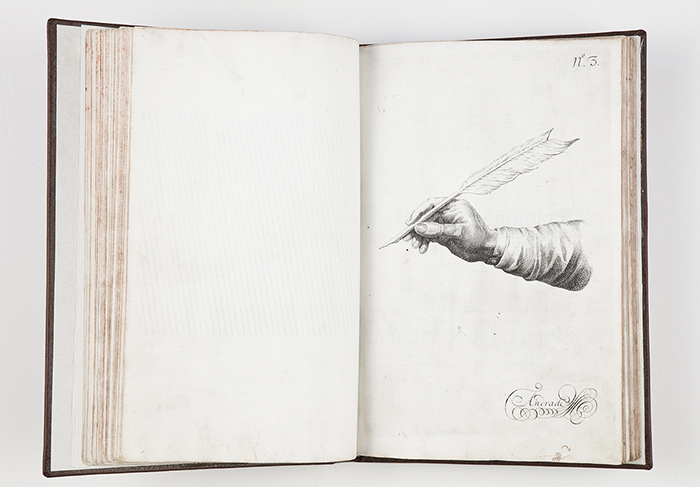

Metamorphosis: the oblique dialogue between poetry and painting

Never has painting been so literary, nor literature so pictorial as during the Baroque. Ana Hatherly’s work also found its place at this border, this place of metamorphosis, between text as image and drawing as writing. It is the “writer’s game” that recreates the world with the word. The artist stated: “My work begins with writing – I am a writer who drifts towards the visual arts through experimentation with the word. Concrete Poetry was a necessary stage, but what was more important still was studying writing itself, printed and handwritten, particularly ancient Chinese and European writing. My work also starts with painting – I am a painter who drifts towards literature through a process of awareness of the connections that unite all the arts, particularly in our society”.

This taste for mobility and fluidity is clear in the drawings that represent-write the wind, the sea, the waves, elements in flight, suspended fragments of writing. Ana Hatherly questioned representation, including the work of art itself– in search of a metalanguage, which was also a theme of the Baroque. In this way she celebrates the reader and proposes a reinvention of reading.