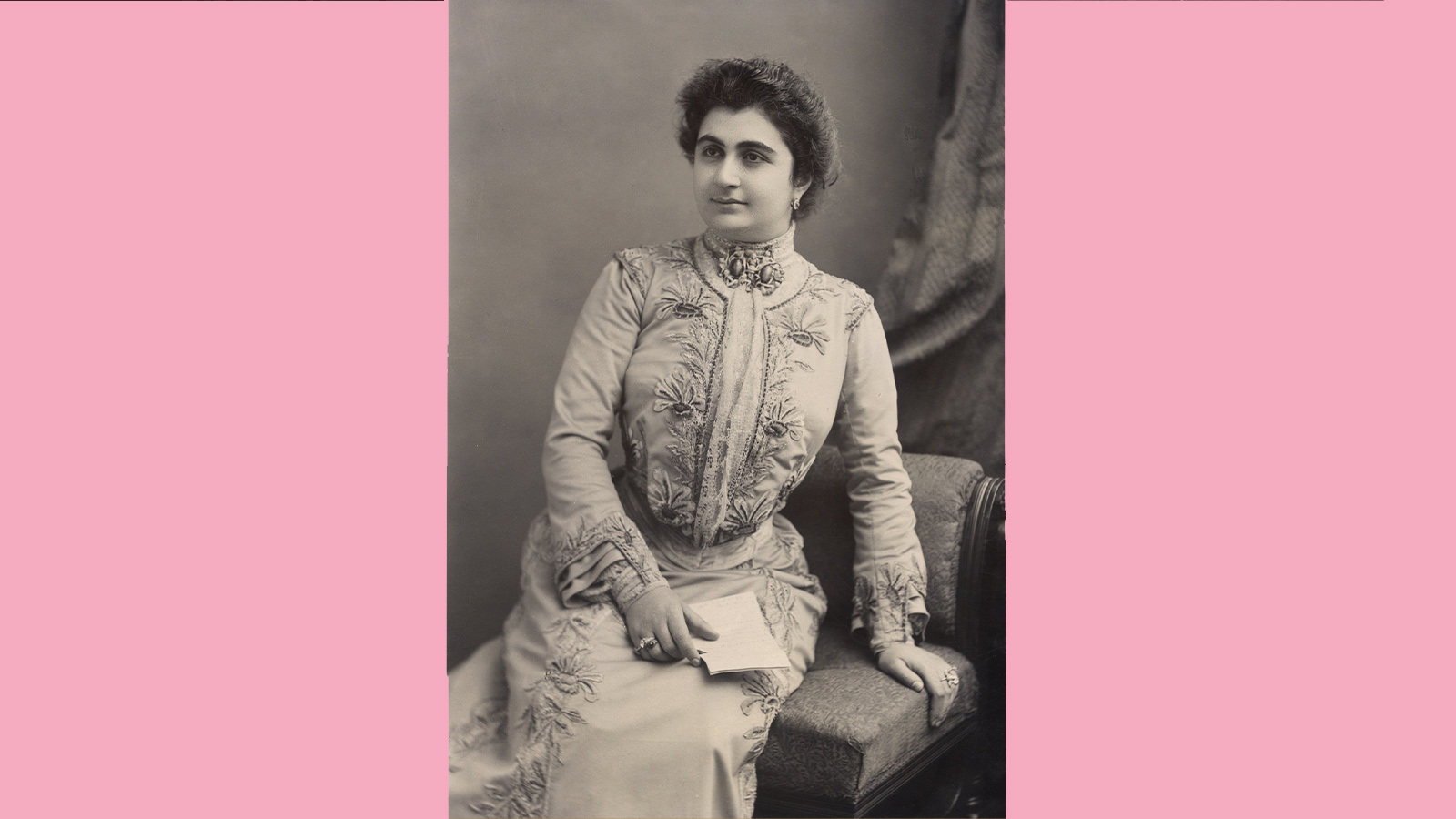

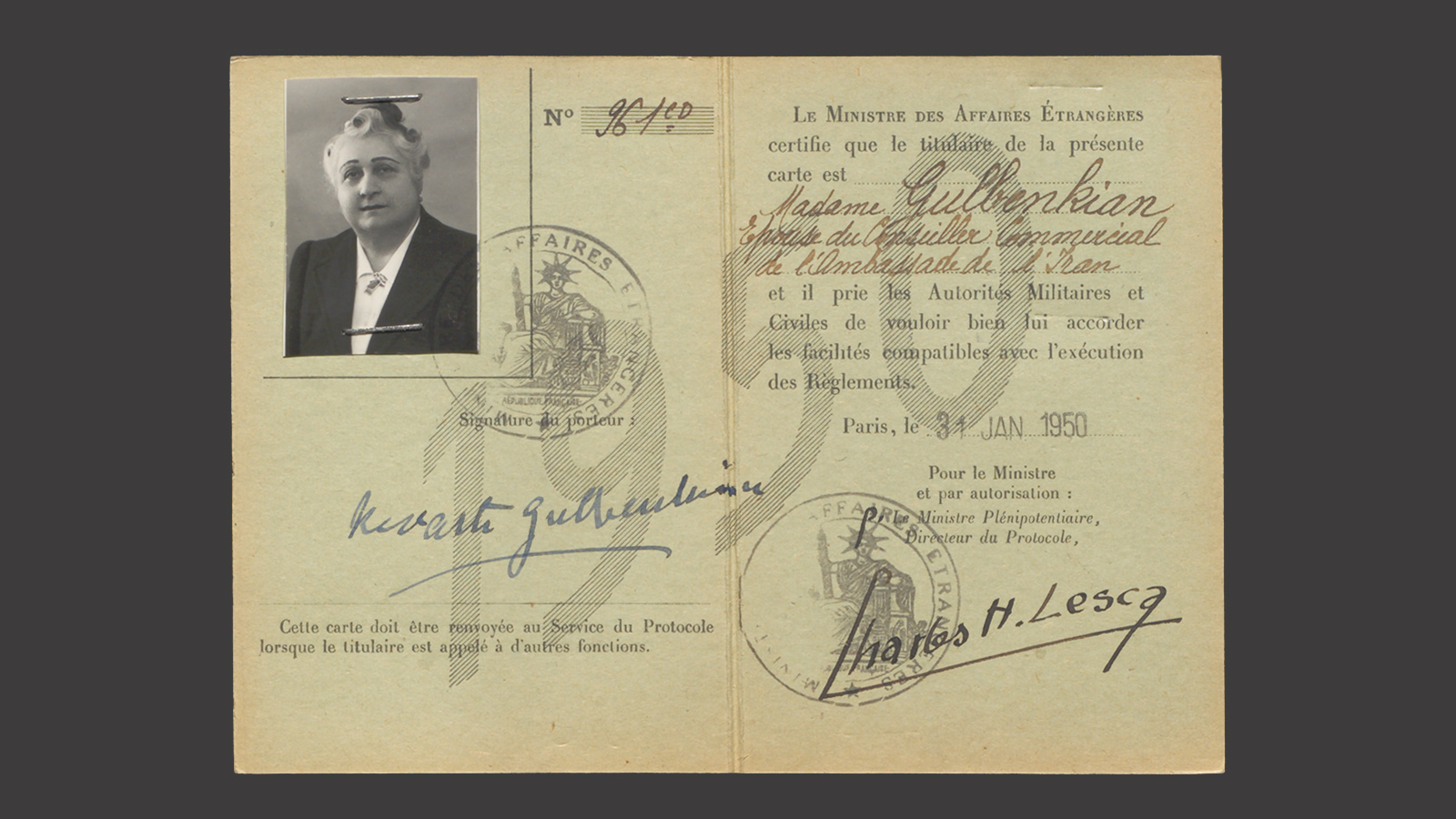

Nevarte Essayan

Memories in the Gulbenkian Collection

Event Slider

Date

- Closed on Tuesday

Location

Calouste Gulbenkian MuseumLike a mirror, the history of a collection reflects the interlinking lives of artists, collectors and art dealers. This exhibition ventures beyond the more visible personalities to focus on another figure: Nevarte Adèle Essayan Gulbenkian. As the wife of Calouste Gulbenkian, she was known as the ‘richest woman in the world’ and, in private circles, the ‘life and soul of the party’. This is a rather superficial characterisation and one that raises two questions: who was Nevarte and in what way does she share in the Collection’s history?

By bringing together objects that, having been acquired by the Collector, were mostly used to decorate Nevarte’s rooms in their London and Paris houses – after leaving Constantinople (Istanbul), where she was born in 1875 – we are able to shed some light on her identity and life story. An Armenian woman, educated, cosmopolitan, extroverted, unconventional and with a lust for life, she forged social, family and emotional bonds that extended from the Middle East to Lisbon.

Nevarte was the only person to accompany her husband and the creation of the Collection for over 60 years. When she died, in 1952, Calouste Gulbenkian cut every red rose from his garden in Normandy to cover her body in the Armenian church in Paris. This was a deeply symbolic gesture. Roses, the Collector’s favourite flower, represented his ‘new rose’, which is the meaning of the name Nevarte in Armenian: նոր վարդ.

Topics

My Dear Calouste

Always Elegant

Genius, but a White Elephant

The Life of the Party

Twenty Thousand Leagues by Land And Sea

-

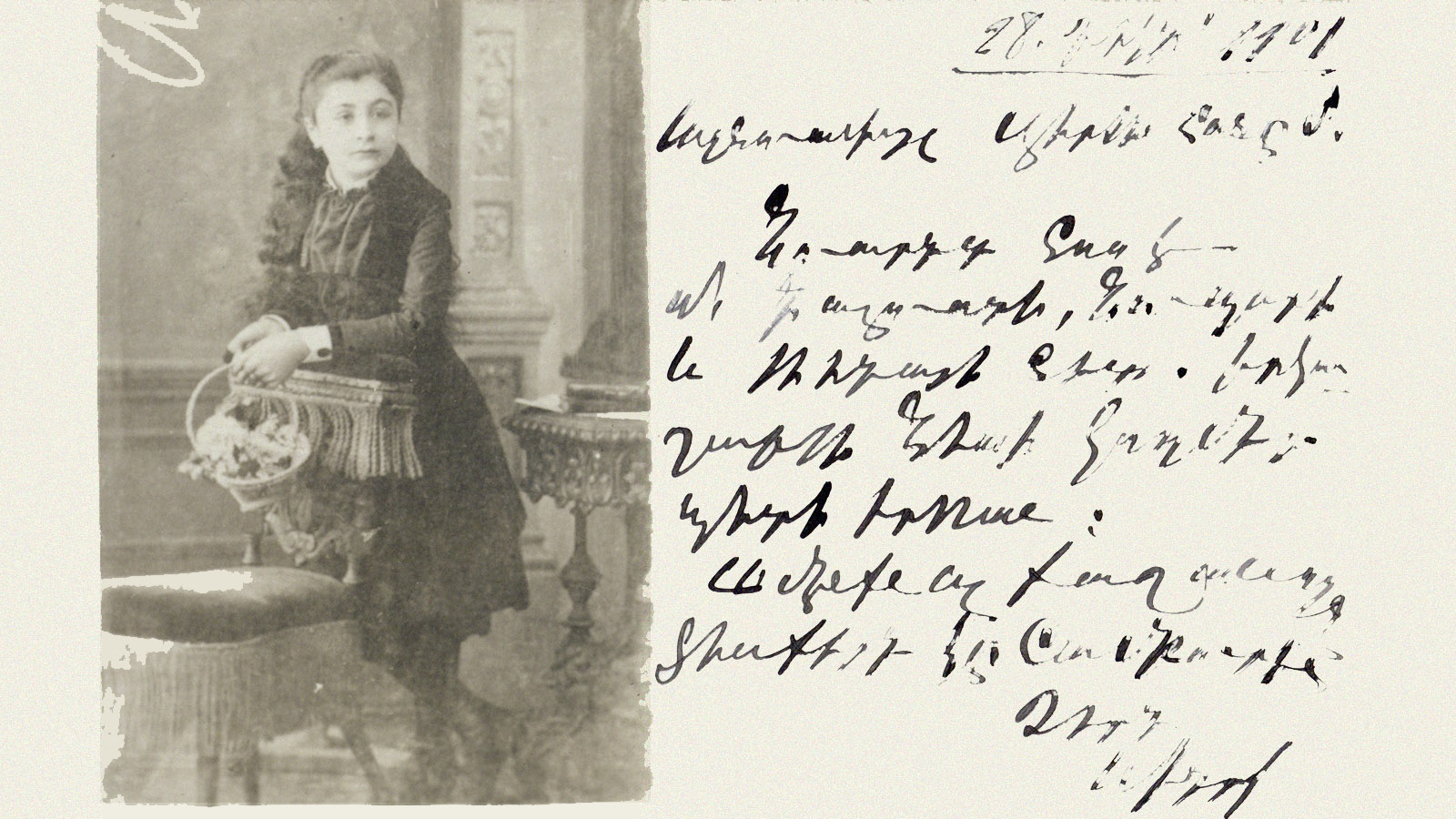

New Rose in Bloom

Nevarte, a name meaning ‘new rose’ in Armenian, spent her early years in Constantinople. Originally from Kayseri in Cappadocia, the Essayans prospered first in commerce and later in banking, expanding as far as Manchester, Liverpool and London.

According to her father, Ohannes Essayan, God had made only one mistake with his family: he made Nevarte a girl and not a boy. He believed that ‘With her intelligence – her tact – her common sense – her energy, she would have been «a business success»’. Such a scenario would have been unlikely, however, even among the Ottoman Armenian elite, at a time when women were only slowly beginning to gain a foothold in the public sphere.

Despite socially imposed limitations, Nevarte received a relatively comprehensive education at home. With the guidance of tutors and governesses, alongside conventional activities such as embroidery, she studied French, English, Armenian and some scientific subjects such as astronomy. In contrast, her brother Yervant studied at Harrow College and Oxford University in England.

-

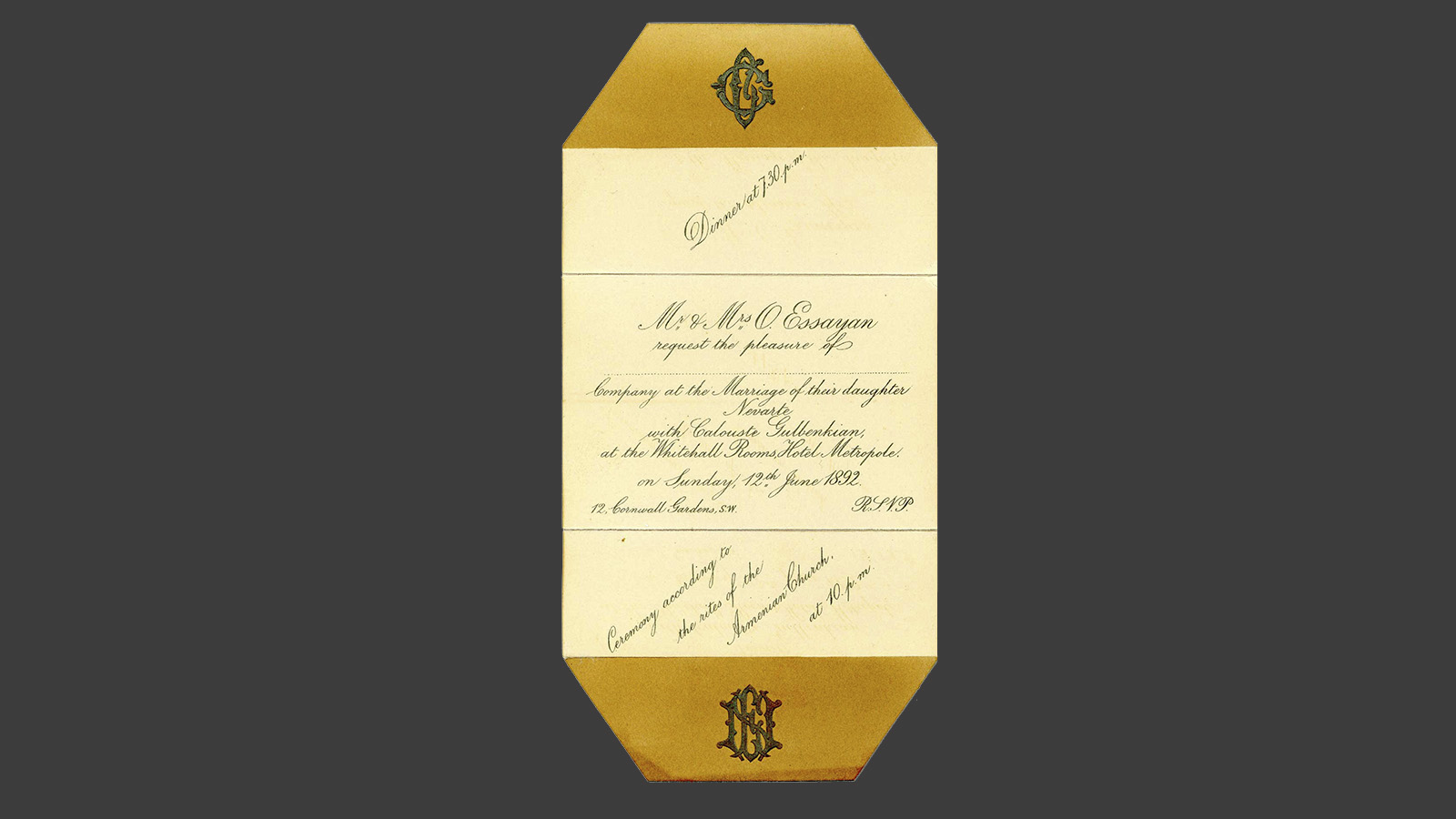

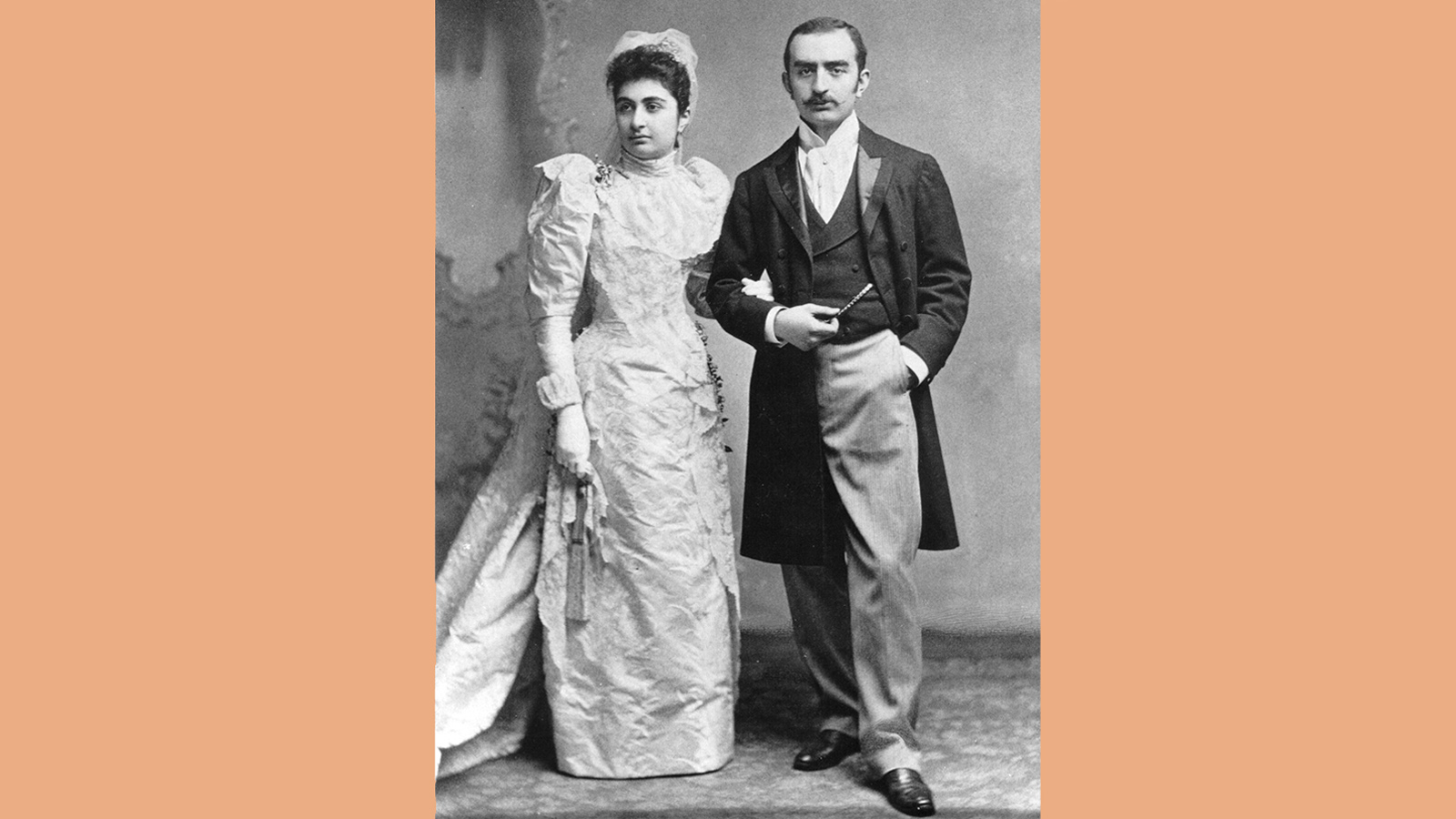

My Dear Calouste

Nevarte Essayan and Calouste Gulbenkian fell in love in the summer of 1889. Their families belonged to the elite circles of Istanbul, frequenting Beyoğlu in the winter, and Büyükdere, where the Essayans had a summer house. Although the two families knew each other well, it took two marriage proposals due to the age of Nevarte, who was only fourteen at the time, before their union was finally accepted.

After years of exchanging love letters, avoiding expressions considered inappropriate, from 12 June 1892, Nevarte freely began to use the expression ‘My dear Calouste,’ which she would continue to use until the end of her life. The wedding, celebrated according to the Armenian rite, took place with great splendour at the Metropole Hotel in London. With no time for a honeymoon, Calouste returned to the offices of C. & G. Gulbenkian the next day.

Nevarte admired her husband’s determination and proved instrumental in the Gulbenkians’ social ascent. Walks in Victoria Park, teas at the Hotel Savoy, and stays in Nice and Cap Martin contributed to this, as did the receptions she organised at the family home in London, where princes, ambassadors, businessmen and artists passed through. At the same time, Nevarte took an active role in the Armenian community, even serving as president of the Armenian Ladies’ Guild.

-

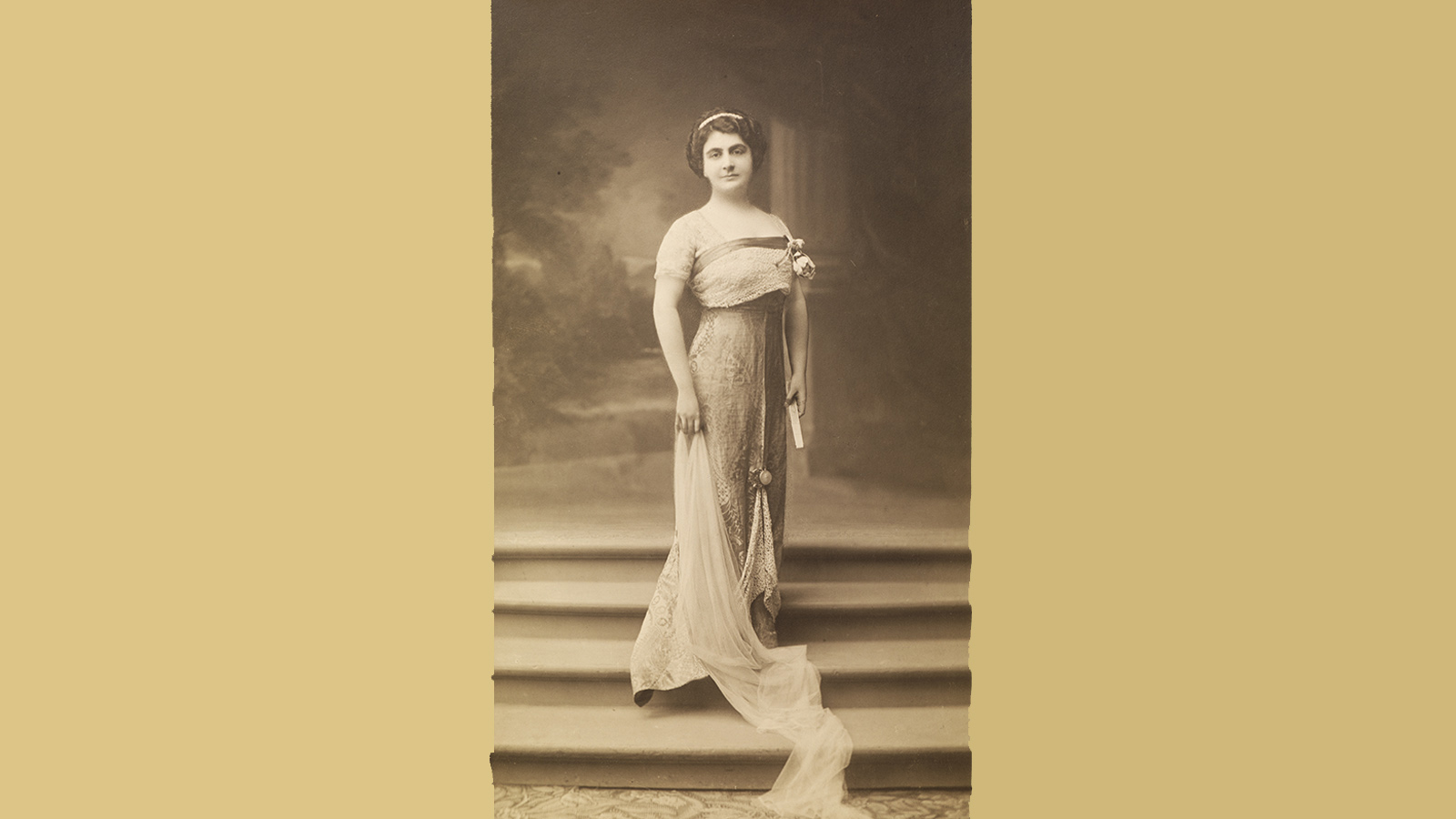

Always Elegant

Nubar Gulbenkian remembered his mother as someone who was ‘always elegantly dressed.’ A woman of her time and very coquettish, Nevarte embraced the emergence of the earliest haute couture houses such as the Callot sisters, famous for their use of antique lace, oriental textiles, elaborate embroidery and ribbons, which captivated her so much.

Nevarte’s taste for the Belle Époque aesthetic extended to jewellery, as she considered the style of the beginning of the century to be ideal for her personality and social status. This predilection, combined with a penchant for emeralds and rubies, led to multiple transactions with major jewellery houses and with Atanik Eknayan, a prominent Armenian lapidarist.

Nevarte personally acquired some of the pieces, such as a Louis XVI style ruby and diamond necklace by Boucheron; others were gifts from Calouste Gulbenkian, including a diamond and turquoise bracelet for their 50th wedding anniversary. On special occasions, she also wore pieces from her husband’s Lalique collection, with which she had herself photographed.

Among the personal jewellery acquired from Lalique, such as a hat pin and a comb, there are also pieces created to Nevarte’s specifications, such as a necklace adorned with 22 rubies, diamonds and plant motifs in enamelled gold.

-

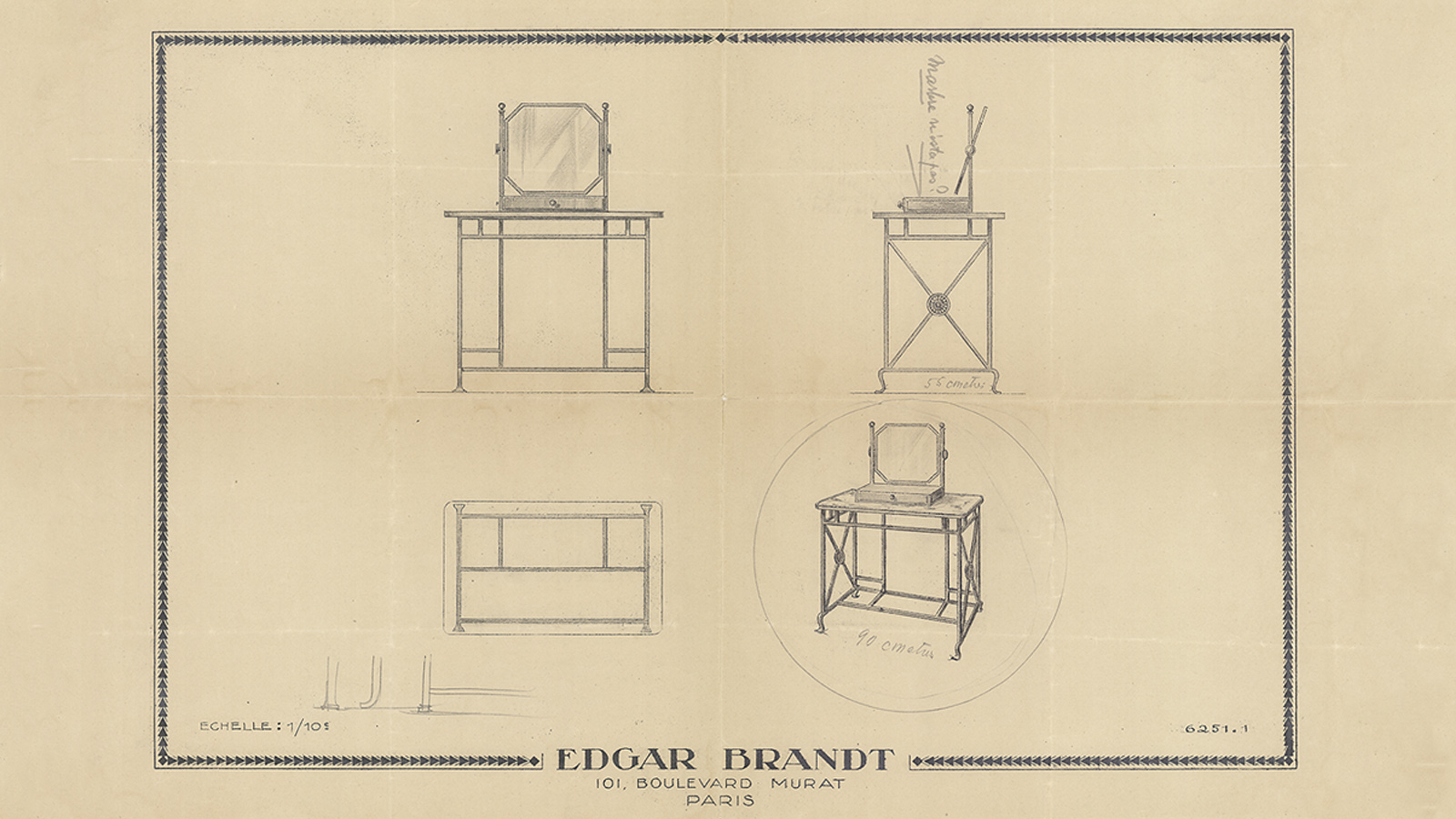

Genius, but a White Elephant

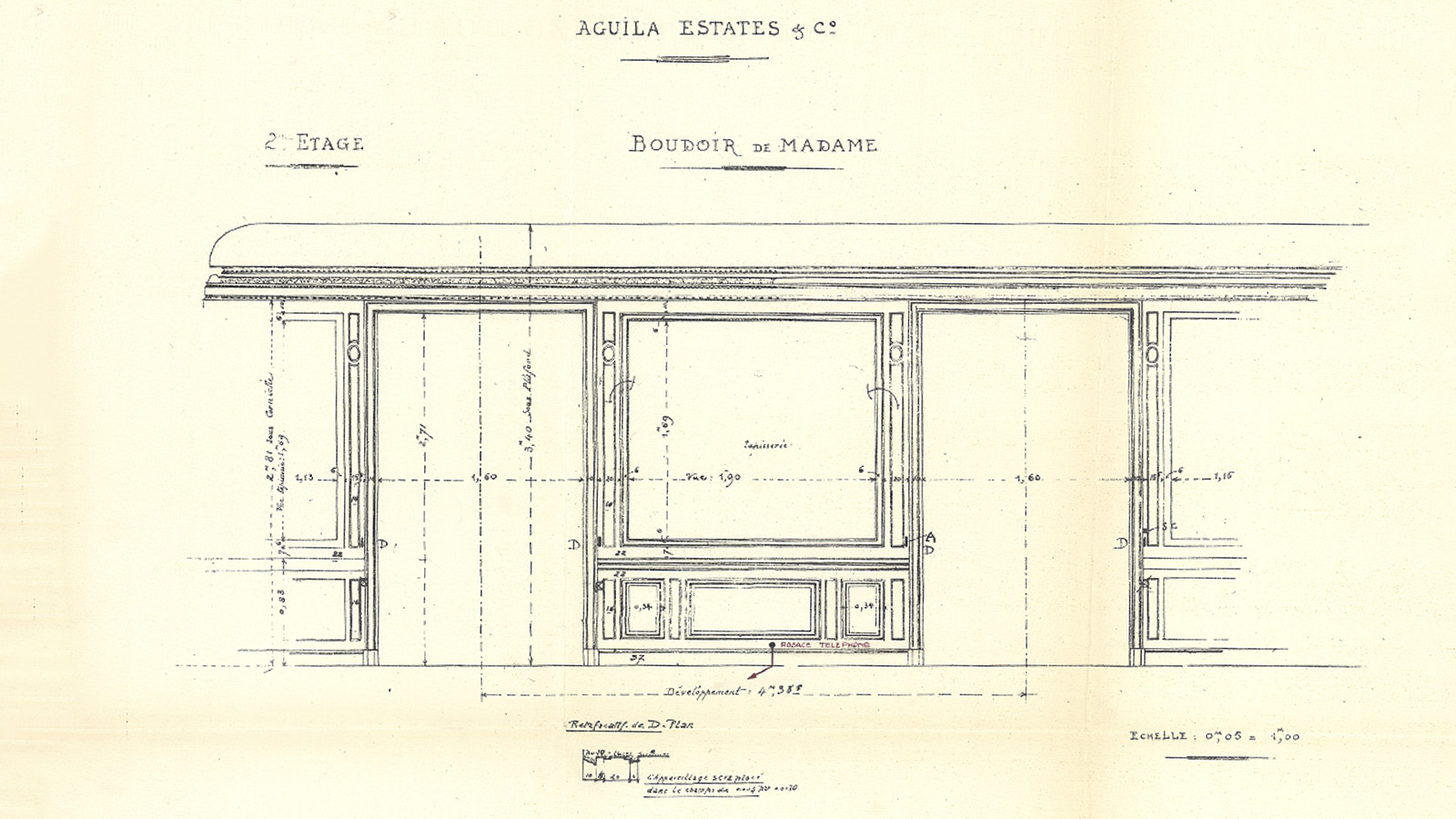

Nevarte had mixed feelings about the hôtel particulier acquired by Calouste Gulbenkian in 1922, both as a family residence and as a space to gather his art collection. Completely refurbished to the Collector’s specifications, 51 avenue d’Iéna was seen as ‘a marvellous creation of his genius,’ but also as ‘a white elephant that was difficult to handle.’ After all, running the house required not only overseeing 105 rooms and 28 employees, but also complying with her husband’s demanding instructions in terms of management, economy and security.

Nevarte’s quarters occupied the second floor and, like many of the other rooms of the house, included works from the collection, over the choice of which she would certainly have exerted influence. Of the different rooms, the boudoir stood out, an oval living room specially designed to receive seven tapestries woven at the Aubusson Manufactory according to cartoons by Jean Pillement.

It was in this space that Nevarte used to take afternoon tea, sitting on a Louis XIV and Louis XV style chair or canapé, after a stroll in the Bois de Boulogne. In the post-war period it became common for her to spend evenings there with her daughter Rita and grandson Mikaël, who was studying the Armenian language, a subject to which Nevarte showed particular commitment.

-

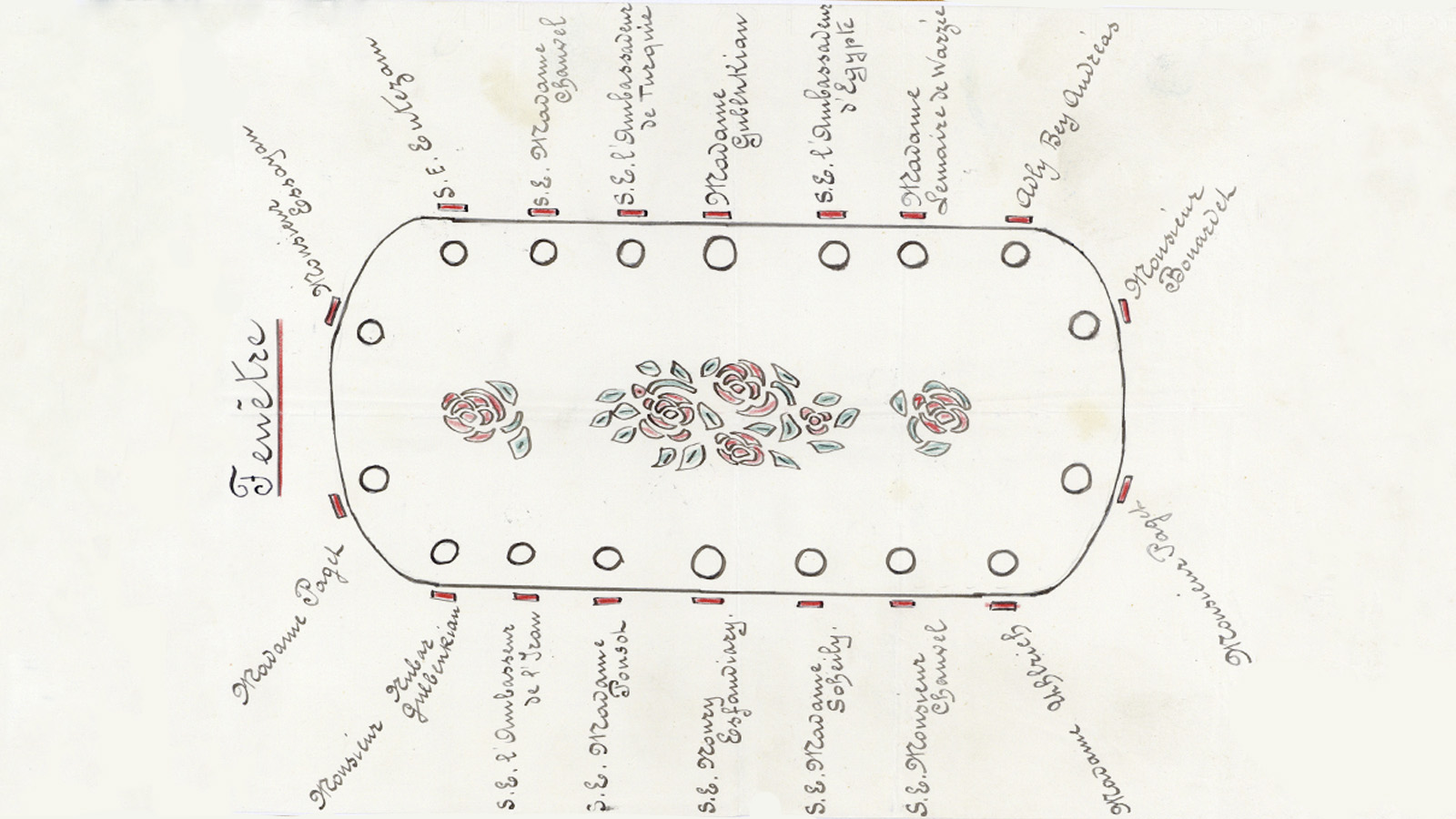

The Life of the Party

Eager to resume post-war receptions at the house at 51 avenue d’Iéna, Nevarte asked her husband in December 1946 to remove Houdon’s Diana and the tapestry La Pipée aux Oiseaux, visible from the entrance, and to reinstall the paintings in the Salon Rond, the reception room on the first floor.

Known for her vivacity and keen sense of humour, Nevarte, often dubbed ‘the life of the party,’ was an ideal counterbalance for Calouste Gulbenkian’s reserved nature, standing out in diplomatic, financial, governmental and aristocratic circles in London, Paris and Lisbon.

The house on the avenue d’Iéna was her stage par excellence, where she received friends and hosted events related to her husband’s activities. This was the case with the lunch offered in 1947 to Princess Ashraf Pahlavi, sister of the Shah of Iran, for whom Nevarte considered a reception in the Salon Rond to be indecent, amidst the nudity of Carpeaux’s Flora and Watts’ Daphne.

An enthusiast of French classical music and Franz Lehár, Nevarte regularly attended concerts, plays and operas, sharing with her husband a predilection for Verdi’s Rigoletto. Much to her chagrin, a growing deafness would end up compromising these moments of enjoyment she cherished so much.

-

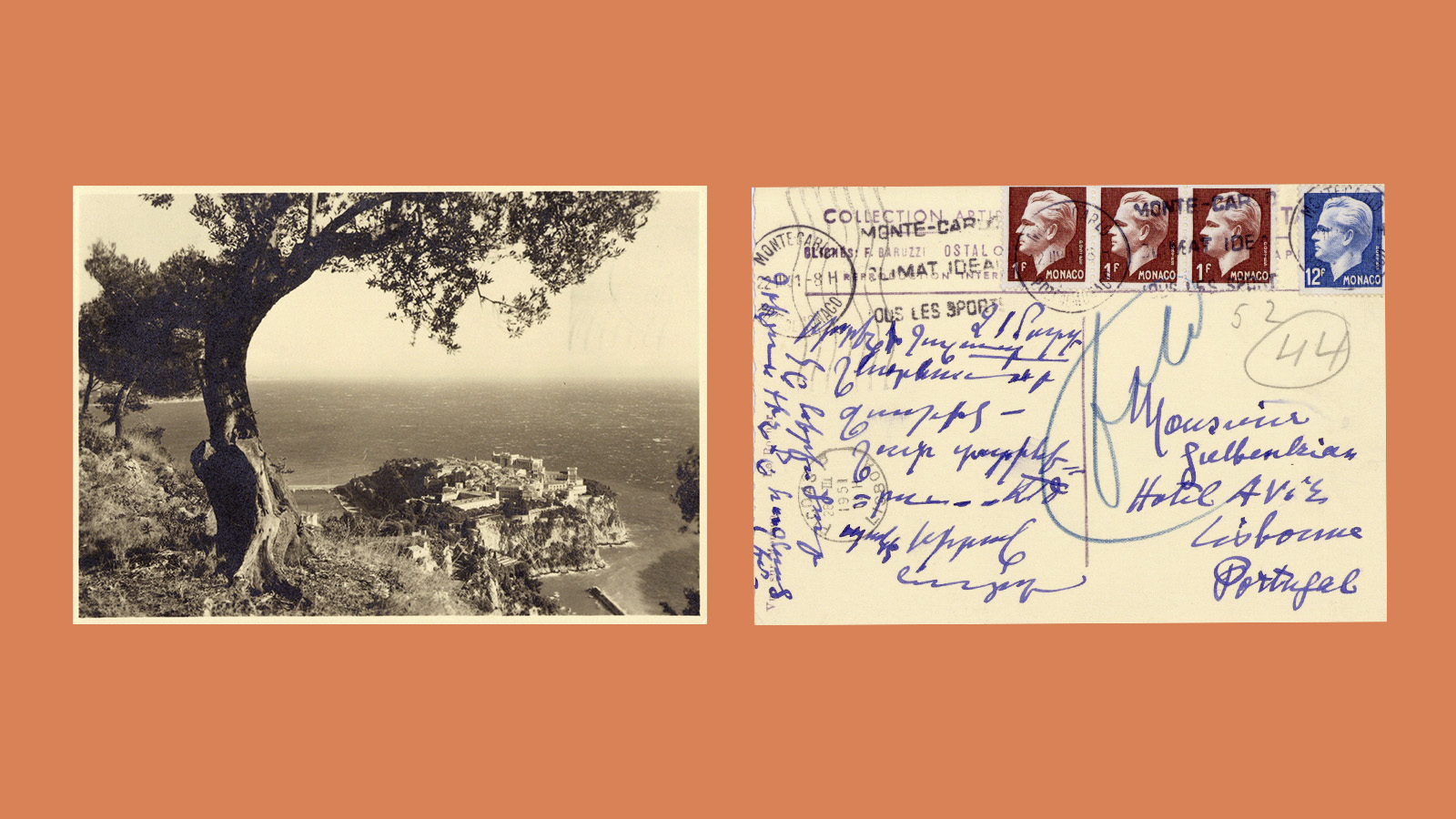

Twenty Thousand Leagues by Land And Sea

Among Nevarte’s objects in the house on Avenue d’Iéna was a collection of books by Jules Verne. These volumes reflected her taste for travel and expanded her range of favourite destinations, real or imagined, usually seaside resorts and spas, such as those of Nice, Évian, Aix-les-Bains, Baden-Baden and Marienbad.

On a different note, in 1923 she planned a trip to Egypt, motivated by curiosity about the discoveries of Howard Carter, to whom Gulbenkian asked permission to allow her to visit Tutankhamun’s tomb. Nevarte knew the country well, had family there, and had fond memories of the time she herself had lived there.

Also unforgettable was a trip to the Middle East in 1935, about which she wrote to Nubar: ‘I’m very excited! I told your father I’d love to go to Baghdad and he has no objections!!!’ The trip was part of the inauguration ceremonies for the Iraq-Mediterranean oil pipeline, at which she was to represent her husband. However, due to a series of difficulties, she ended up completing only half the itinerary, travelling no further than Jerusalem.

One of her last major trips was to Lisbon in 1942, where she stayed until 1946. Away from the privations of war and perfectly integrated in the local community, she attended diplomatic receptions, shows at the Teatro São Carlos, and competitions at Estoril Golf Club, as well as Portuguese lessons and visits to the Cascais Library.

Credits

Curator

Vera Mariz

Image at the top

Andreia Constantino