Power of the Word I / Pilgrimage / Hajj

A group of Arabic speakers living in Lisbon recently gathered to unlock some of the inscriptions in the Middle East gallery, which are mainly religious; among the participants were artists, students, professors, translators, religious scholars and atheists. Together, they revealed words and shared words, and then associated a selection of them with seven objects.

Seven is a special integer. It is the number of verses in the Opening Chapter of the Qur’an (al-Fatiha), recited by all Muslims, and the number of pillars of the Hajj, the annual pilgrimage to Mecca. Hajj is both a real journey, taken once in a lifetime, and a metaphor for the movement of life. Many cultures and religions have their own journeys and this project was created with the word ‘co-existence’ in mind. In the case in the gallery, the display can be read from the left, like this text (nos. 1–7), or from the right, in accordance with Arabic script (nos. 7–1), as explained here at the end.

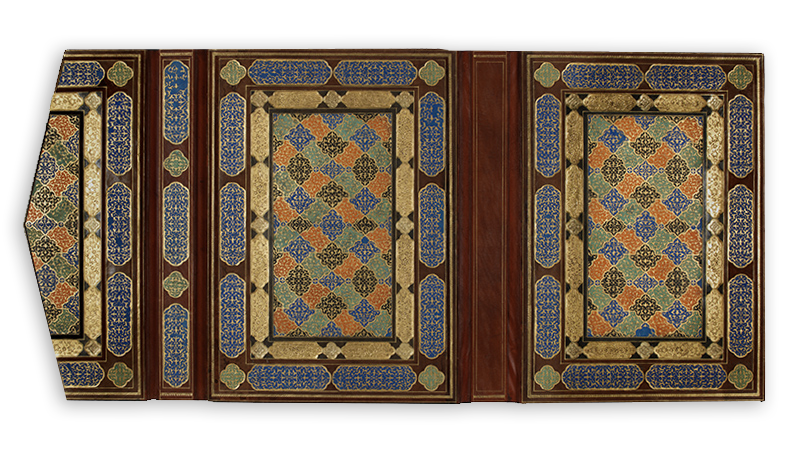

Reveal and Conceal / Kashf wa hajb

This bookbinding once enclosed a precious copy of the Qur’an and was chosen by the group to serve as a metaphor: an object that both reveals and conceals its contents. For Muslims, the Qur’an is the Word of God, revealed in Arabic to the Prophet Muhammad through the Archangel Gabriel, from c. 610 until 632. It is first and foremost an oral tradition and Qur’an literally means ‘the recitation’; the empty space concealed by the binding evokes these spoken origins.

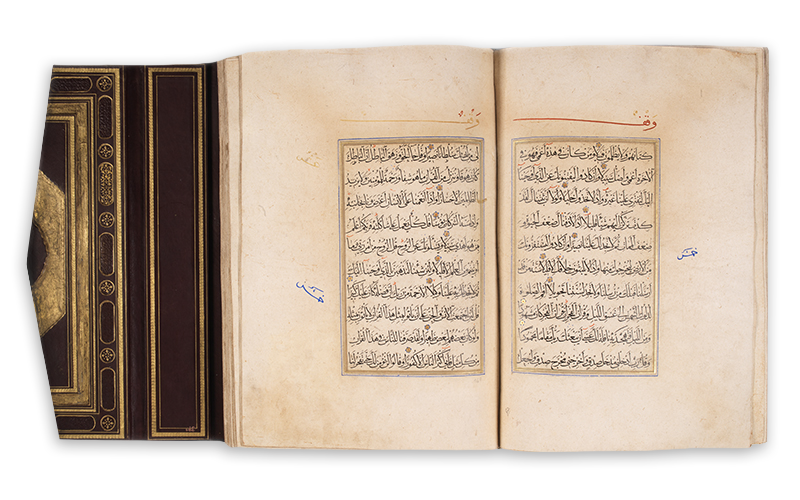

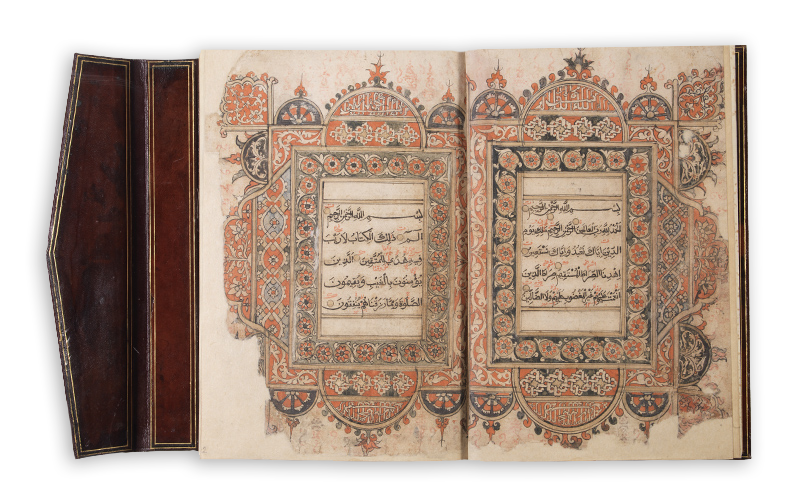

The Opening / Al-Fatiha

This Iranian copy of the Qur’an contains the Words revealed to the Prophet Muhammad in the city of Mecca, before his flight to Medina in 622. The first chapter (al-Fatiha), seen here, is a prayer for the guidance, lordship and mercy of God (Allah) which opens with the Bismillah (In the name of God), repeated abundantly by Muslims. Allah is the Arabic name for God, like Yahweh in Hebrew, Deus in Portuguese, or Dieu in French.

Endowment / Waqf

The group made an important discovery: this Qur’an was gifted by a woman to a mosque in Cairo in 1622–3. Qur’ans often serve as offerings and the Arabic word waqf (endowment) is repeated along the top. The 22nd chapter, open here, calls upon the faithful to join the Hajj (pilgrimage). Both women and men are expected to undertake this journey, and the Hajj authorities are currently considering allowing female pilgrims to perform the pilgrimage unchaperoned.

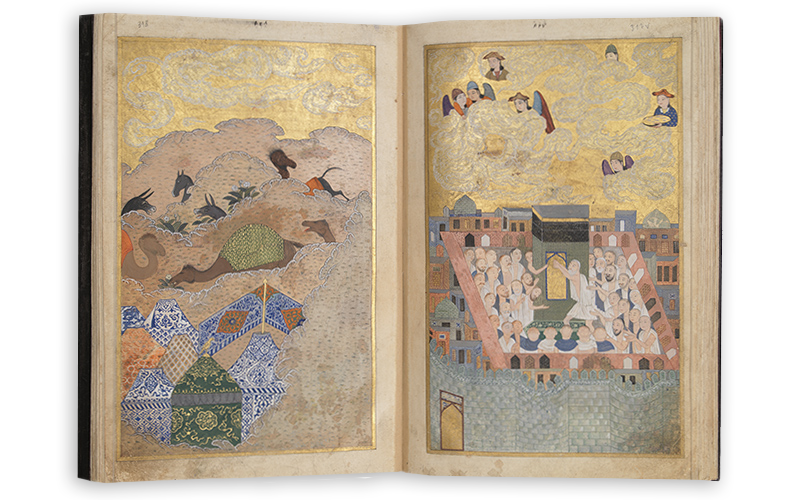

Cube and Circle / Ka’aba wa dayira

The Ka’aba, literally ‘The Cube’, made of black stone and bricks, is the focus of the first and last rites of the Hajj, called tawaf, in which pilgrims perambulate in an anti-clockwise direction around it seven times, with their heads shaved and wearing white cloth (ihram). The intense sensation of approximating the Ka’aba has been described as ‘magnetic’. Circumambulation is also an integral part of Buddhist and Hindu devotional practices.

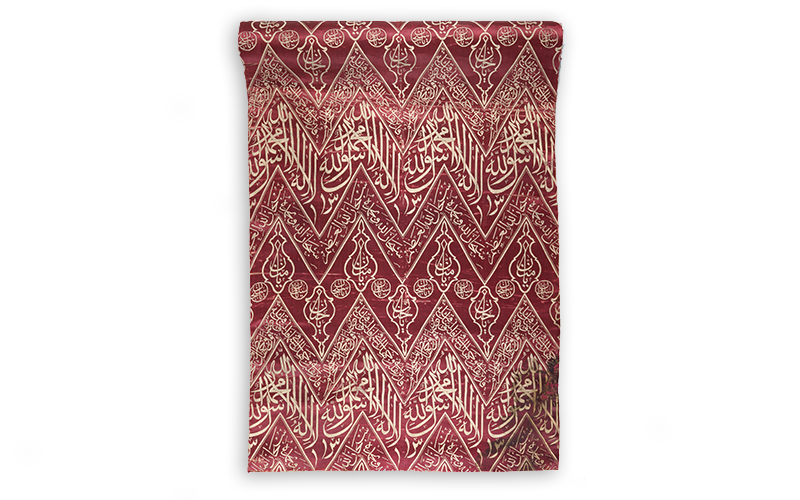

Light / Nur

A form of lamp bearing two of the ninety-nine names of God – Ya Rahman (Merciful) and Ya Mannan (Perfection) – is finely woven into this textile. In the Qur’an God is compared to a lamp which is lit like a scintillating star. Red silks of this type were hung inside the Ka’aba (‘The Cube’), which despite its dark exterior, is perceived to emanate light. The dramatic organization of the religious inscriptions on the textile, in steep chevron bands, admirably conveys the flickering light of dancing flames.

Multicultural / Mataadid attakafat

During the Hajj, pilgrims arrive in Mecca ‘from every distance place’, bringing together a plurality of languages, ethnicities and nations, leading to vibrant cultural exchange. This Qur’an was made in Aceh, Sumatra (Indonesia), an important historical port since the fourteenth century for the embarkation of Asian Muslims, giving it the epithet Serambi Mekah (Varanda of Mecca). Today three million Muslims from across the world gather in Mecca annually.

Supplication / Duaa´e

This bowl is inscribed with blessings which act like an amulet, appealing for health, happiness and lasting progeny. Written upside down they can only be read when you bend over the bowl, as you might when washing for prayer. Calouste Gulbenkian (1869–1955) was an Armenian Christian who could not read Arabic, but he was born in Istanbul, which at that time was half Muslim and half Christian and Jewish. This context of religious co-existence explains in great part his interest in Islamic art.

A Spiritual Journey | Hajj

Surprisingly, the group’s discussions revealed that this display can also be read in the reverse direction, from right to left in the gallery, according to Arabic script (nos. 7–1), this time as a personal spiritual journey: beginning with the ceramic bowl with its phrases of supplication, asking for God’s intervention, which is the first step towards faith; followed by the Indonesian Qur’an which reminds us that faith can arise anywhere; then the red silk textile inscribed with the Shahada, the profession of faith, the first of the Five Pillars of Islam; proceeded by the image of Mecca which is at the heart of the religion, then the waqf (endowment) manuscript, a reminder of the third pillar, Zakat (Alms); and finally the most important chapter of the Qur’an, al-Fatiha (The Opening), which guides spiritual life, while the bookbinding at the end metaphorically ‘clothes’ the Word of God as well as the now-devout Muslim.

Guest Curator: Hassane Ait Faraji

Faculdade de Belas Artes, Universidade de Lisboa

Coordinated by Jessica Hallett (curator) and Diana Pereira (Education Department)

Calouste Gulbenkian Museum

Collaboration: Fabrizio Boscaglia, Jad Khairallah, Maryam Loutfi, Rahman Nighighi, Shahd Wadi, Sheila Namazi, Sheikh Zabir Edriss e Yasir Aboobakardaud.

Power of the Word is a participatory curatorial project at the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, involving principally Arabic and Persian speakers who join curatorial and educational staff and guest researchers to study the Middle East collection. It aims to enhance our experience of these works by encouraging collaborative research and vibrant, contemporary interpretations which affirm intangible culture.