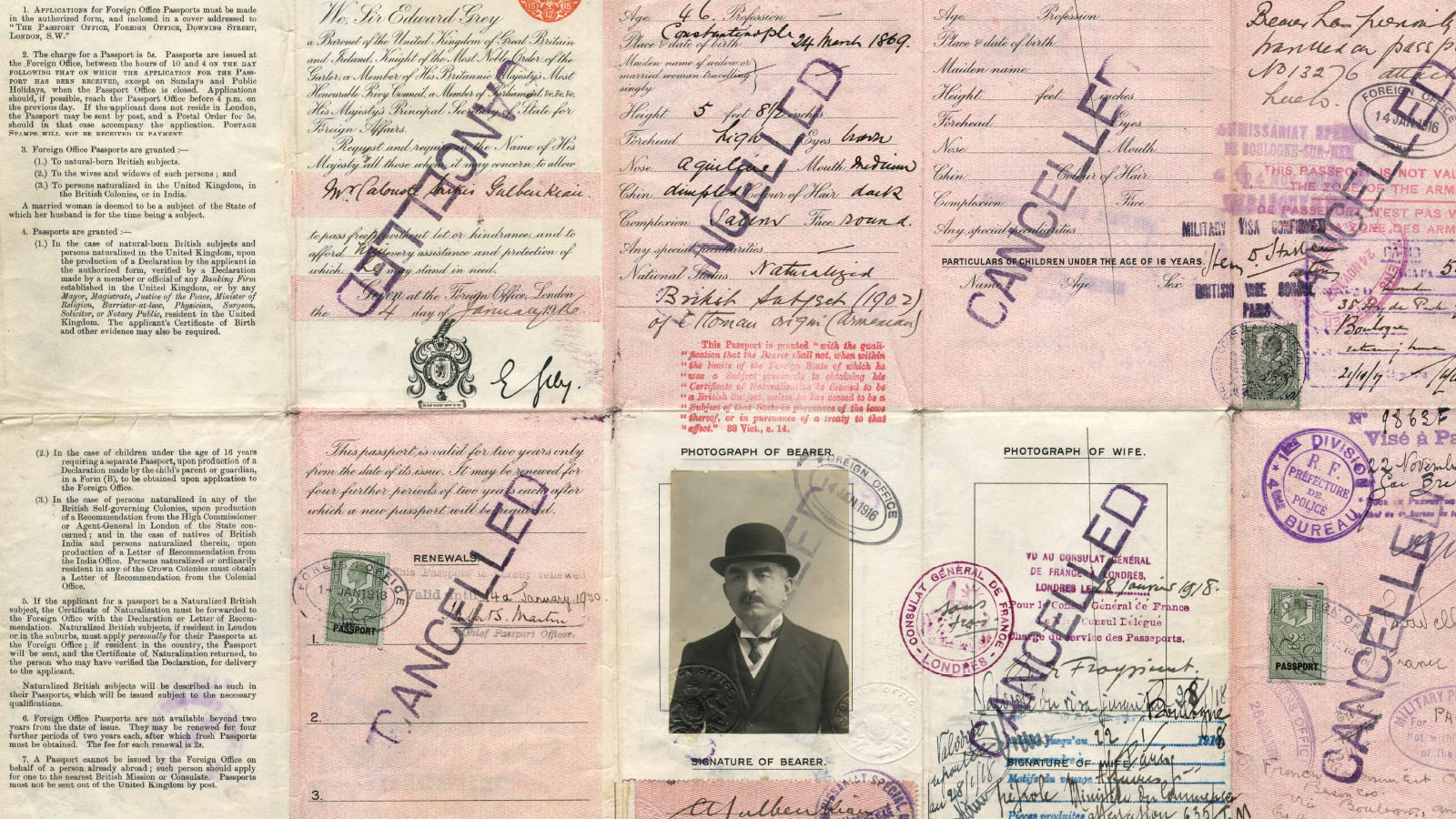

Packed and ready: Calouste Gulbenkian’s travels

In Calouste Gulbenkian’s world, the concept of ‘holiday’ was famously fluid and the word itself rarely formed part of his lexicon. Episodes like the one described below were therefore quite common. Ever attentive to the oil and art markets, in May 1932, the Collector took advantage of a stop made by the yacht he was travelling on, in Tunis, North Africa, to put his affairs in order. Among the letters he sent was one addressed to Edward Fowles, confirming his interest in seeing a writing table from the Oranienbaum Palace, which had been nationalised during the Russian Revolution.

This was the second of two Mediterranean cruises, each lasting over a month, which gave Gulbenkian some credibility as a seasoned traveller when it came to counselling Fowles, a representative of the Duveen Brothers firm of art dealers, against such an experience: ‘All these cruises and sorts of things are humbugs, so I can give you a good advice that neither you nor Mrs. Edwards indulge in so called luxuries.’ His displeasure might have been related to a persistent fever he endured throughout the trip, but this ended up being the last time Gulbenkian ventured on a similar experience.

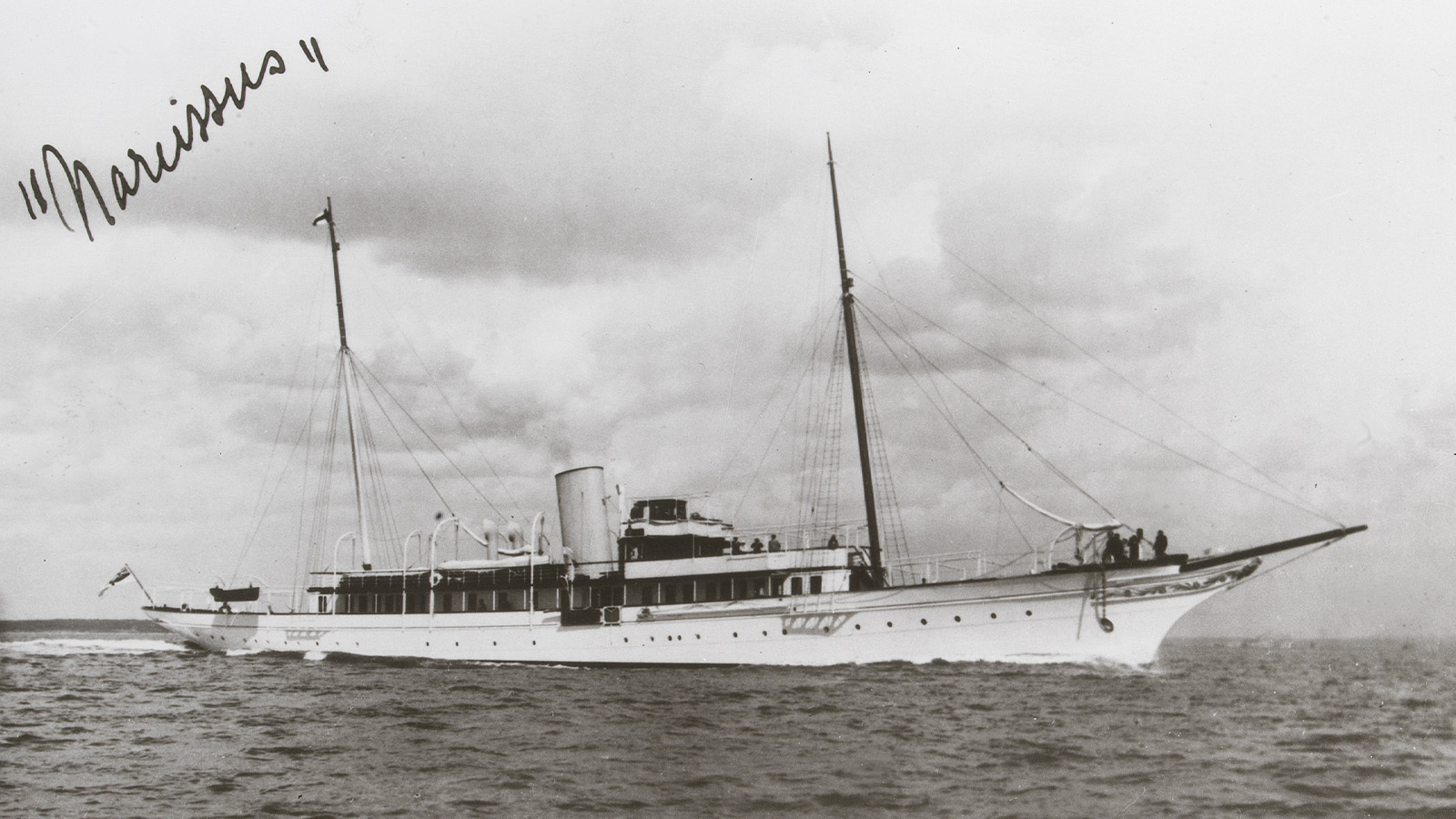

In his opinion, the conditions and amenities of the yacht Narcissus paled in comparison to those of a hotel, with the small size of the bed and bathtub being two of the main deterrents. In fact, whether in hotels or his various homes, Gulbenkian always attached great importance to these aspects, reflecting his steadfast devotion to comfort and quality of life. The bathtub in his Paris home, for example, was designed to resemble the one in the suite he usually occupied at the Ritz Paris hotel.

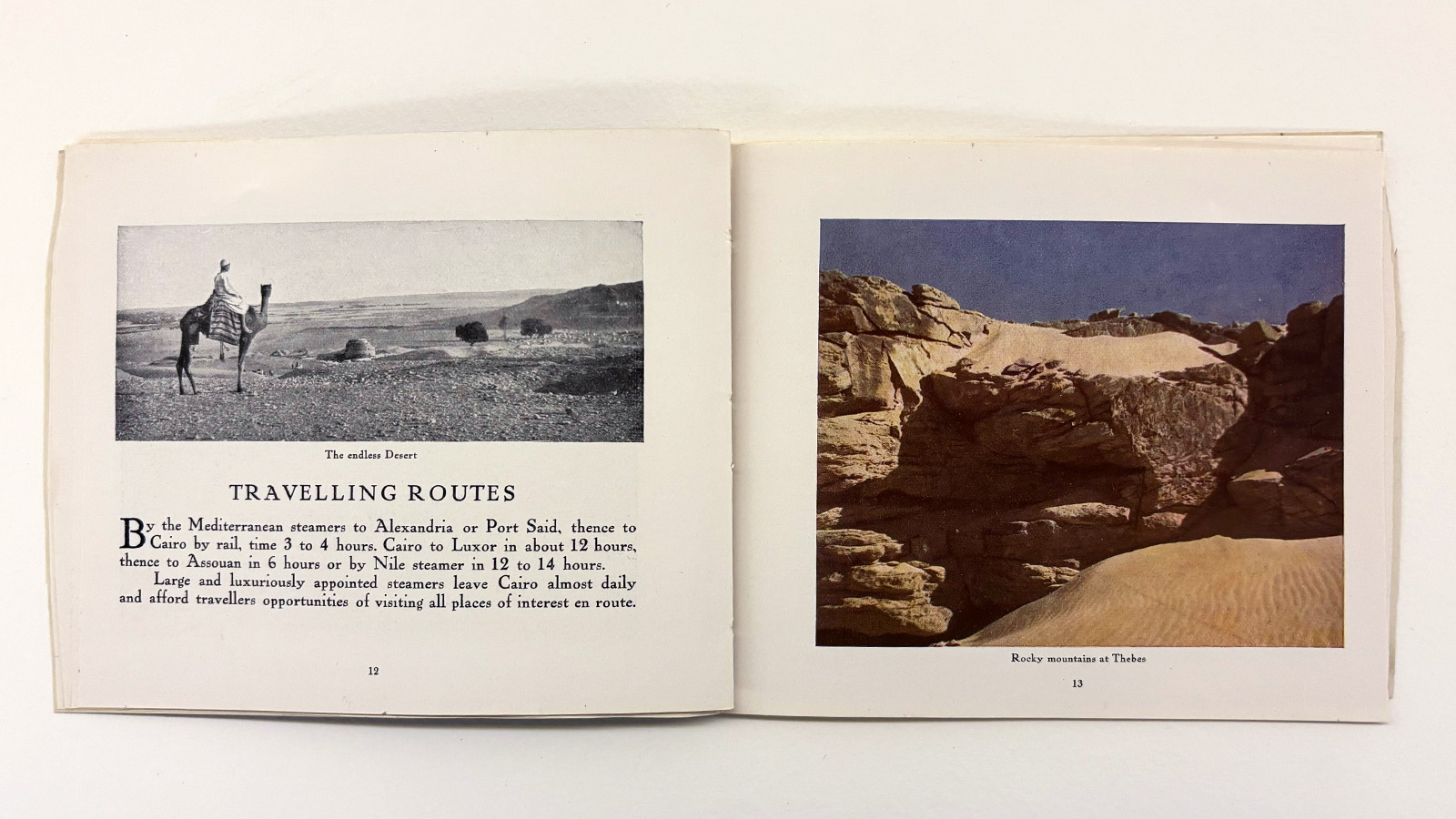

That cruise was one of a series of trips taken between 1928 and 1934 as part of the Collector’s historical and artistic education. These included visits to the Museo del Prado in Madrid, the Royal Alcázar of Seville, the Museo Poldi-Pezzoli in Milan, the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence, Pompeii, the Acropolis in Athens, the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, St Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican, Aswan, Jerusalem, Baalbek and the Musée des Tissus in Lyon. These and other visits to museums, historical sites and monuments allowed Gulbenkian to cultivate a more informed and critical eye. Through careful examination, he reflected on the quality of the artworks, comparing them with those in his collection, refining his taste, and laying the groundwork for future acquisitions.

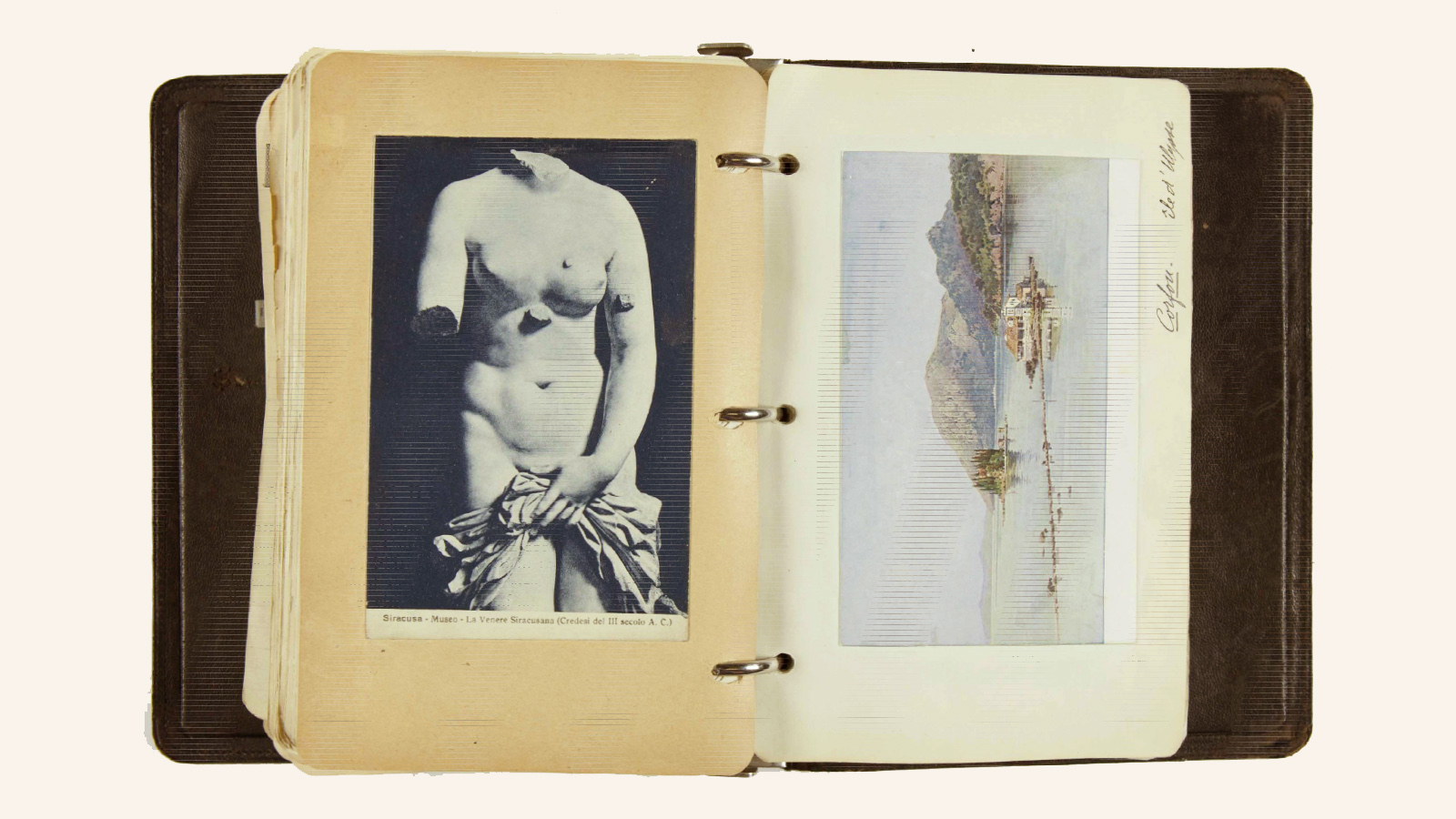

Among his favourite activities during these breaks was visiting and contemplating gardens and landscapes, underlining his keen interest in nature, which, like art, was seen as a haven and source of comfort. This is evident in the numerous observations and notes recorded in his travel diaries, along with postcards and photographs, intended to aid his own future recollection.

Short-term stays in locations close to his Paris and London offices were more frequent, although these were not necessarily regular. In addition to sojourns in Fontainebleau and Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Gulbenkian regularly spent a few days in Deauville. In 1927, he even bought a property near this city in Normandy with the intention of creating a garden there. However, the project did not include a house, as Gulbenkian preferred to stay at the iconic Hotel Normandy.

Highly selective in his choices, this luxurious seaside resort was part of the hotel circuit habitually frequented by the oil tycoon, which included the main tourist and leisure destinations for international elites: Cannes, Aix-les-Bains and Biarritz. Although he never completely switched off from business, whilst there he would spend part of his days taking long walks. From these moments of pure contemplation, the Collector retained a special memory of the way the fog would shroud the sea in front of the Hôtel du Palais Biarritz, as if the waves were emerging from a white mantle illuminated by the lighthouse. It was a spectacle so breathtaking that, as he himself acknowledged, not even a William Turner painting could match it.

During these trips, in addition to choosing good hotels where he generally booked the same rooms as in previous stays, restaurants were also carefully selected. For a demanding gourmet like Gulbenkian, the quality of the food, the cooking techniques, and the presentation of the dishes were paramount, which is why he described the food served at the Hotel du Palais in Biarritz as ‘awful.’ Conversely, the selection of cheeses and excellent French cuisine at the Hotel Vier Jahreszeiten’s restaurant in Munich earned effusive praise.

As an alternative to seaside, spa resorts and cruises, Gulbenkian even considered buying an island to serve as a holiday home where he might enjoy some privacy. In addition to the island of Sainte-Marguerite, off the coast of Cannes, he showed interest in the island of Polvese, in the Umbria region, confessing: ‘I am rather keen on acquiring a very beautiful island if it possesses great conveniences, is naturally very pretty with big trees, fine scenery and woods and if it is in every way a sympathetic place.’

A lover of aesthetic sophistication and the high-quality techniques and materials employed by luxury brands, Gulbenkian purchased a selection of Louis Vuitton travel cases. Founded in 1854, the Parisian brand became famous for its innovative solutions, which replaced the domed travel trunks that had become obsolete following the revolution in transport and communications. As an alternative, flat-topped chests emerged, which were easily stackable, made of wood and covered with a durable, waterproof canvas, making the whole structure considerably lighter.

Among the cases Gulbenkian purchased was a wardrobe trunk, a model that had been on the market since 1875. Ordered in 1911 from the store on Rue Scribe in Paris, it was customised not only with the ‘CSG’ monogram, but also according to the Collector’s specifications, allowing space for an apothecary box also created by Louis Vuitton. Attesting to Gulbenkian’s constant concern for his health, the order included precise references to the different types of medicine bottles that would need to be packed in the trunk.

These medicines were also included in one of Gulbenkian’s travel checklists, along with passports and visas, stationery and envelopes, business cards, blotting paper, a copy book, an address book, telegraph codes, a cheque book, a pencil and a pen. Besides the materials needed to pursue his busy business activities, he also included food staples, such as fruit, wines and champagnes, coffees, cold dishes, grissini and honey. Sunglasses, binoculars, and two small folding chairs, probably for birdwatching, completed the list of essential travel items for Calouste Gulbenkian.

Image at the top: Wardrobe trunks and a shoe case, Louis Vuitton, with the monogram of Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian (CSG). Photo: © Catarina Gomes Ferreira