Books of Hours in the Gulbenkian Collection

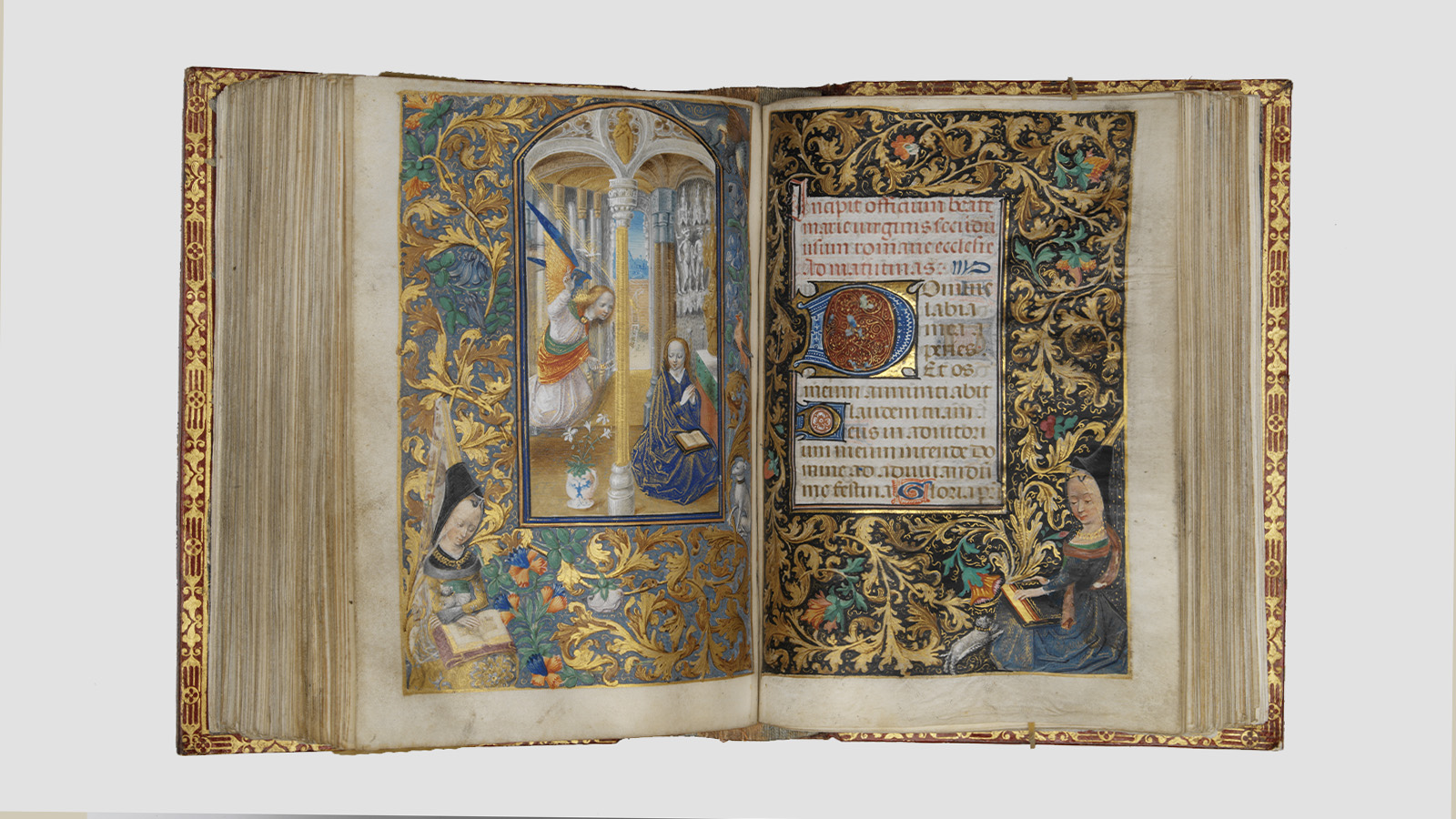

Forming part of his collection of 35 illuminated manuscripts, Calouste Gulbenkian acquired around 16 books of hours, including codices and loose leaves, highlights among which are the Book of Hours of Margaret of Cleves (fig. 1) and the Book of Hours of Isabel of Brittany (fig. 2), for their historical and artistic significance.

The increase in production – and resulting increase in market availability – of manuscripts during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, as the centres of creation moved from rural monasteries to the cities – where the number of commissioners was growing – combined with Gulbenkian’s preference for abundantly and luxuriously illustrated books over more modestly decorated ones, probably lies at the heart of this great interest.

A typology created in Europe from the second half of the thirteenth century onwards, Book of Hours contain prayers intended for private devotion, particularly by laypeople, at a time when social life was progressively moving from rural fiefdoms to cities, where, in addition to the wealthy nobility, a bourgeois class was also starting to become established.

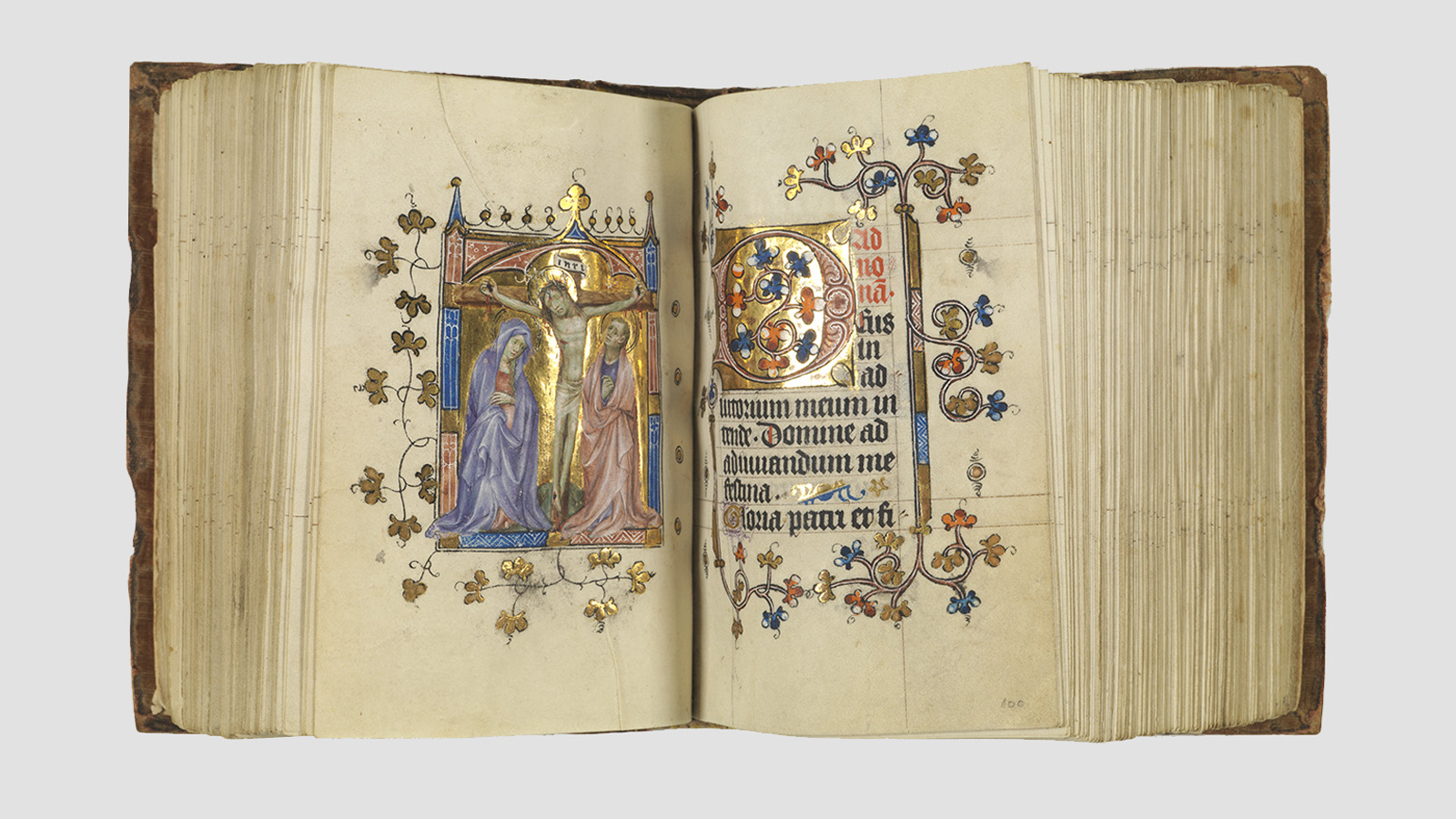

The fact that these books were commissioned by wealthy patrons for their personal use or as gifts (for example, as wedding presents), and not to be used as part of formal worship, explains their small, often miniature size (fig. 3), which made them easily portable. In addition, these books appear to follow a stable structure, which has been conventionally established over time, although some show specificities relating to the period, place of production or the patron.

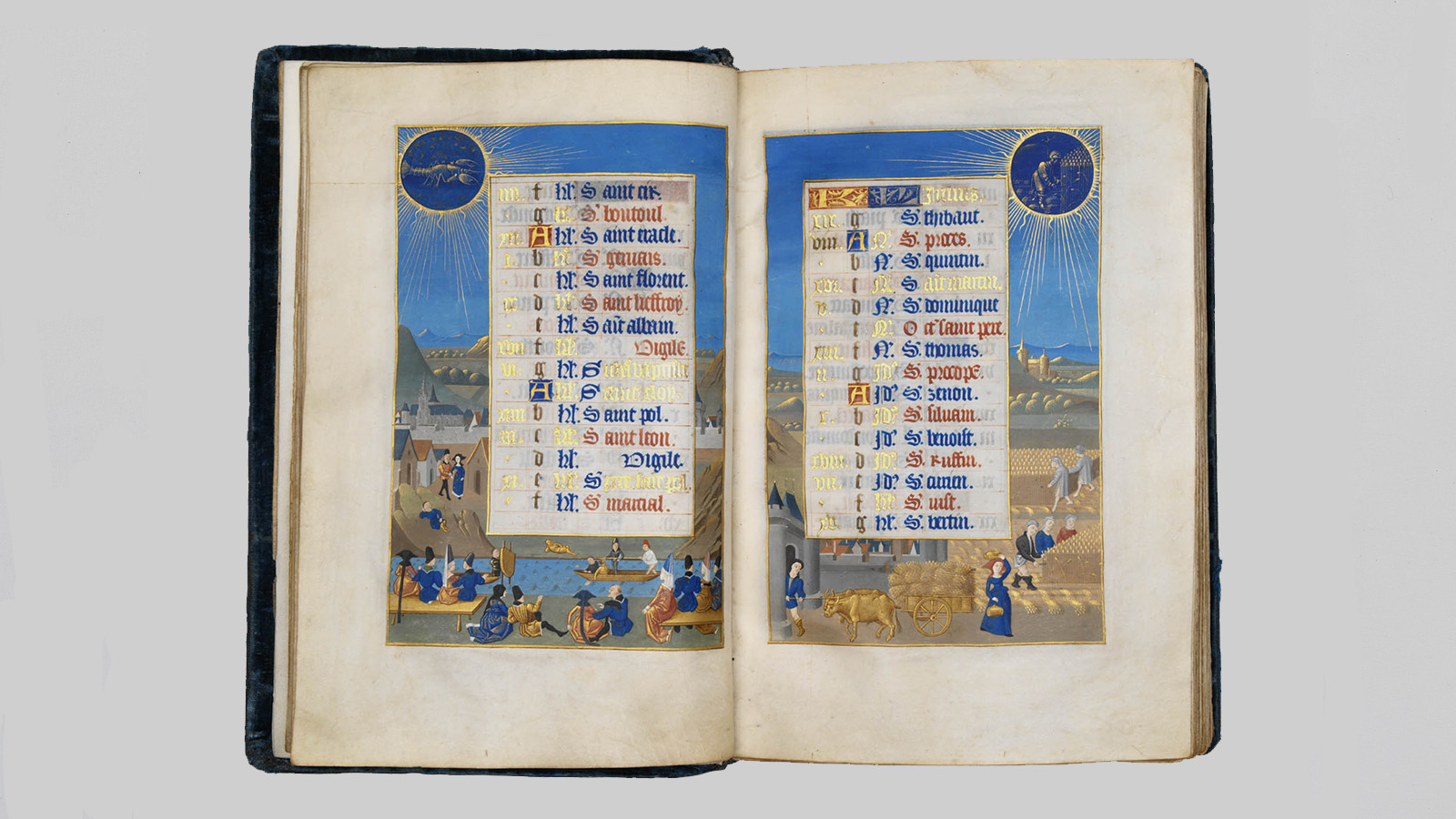

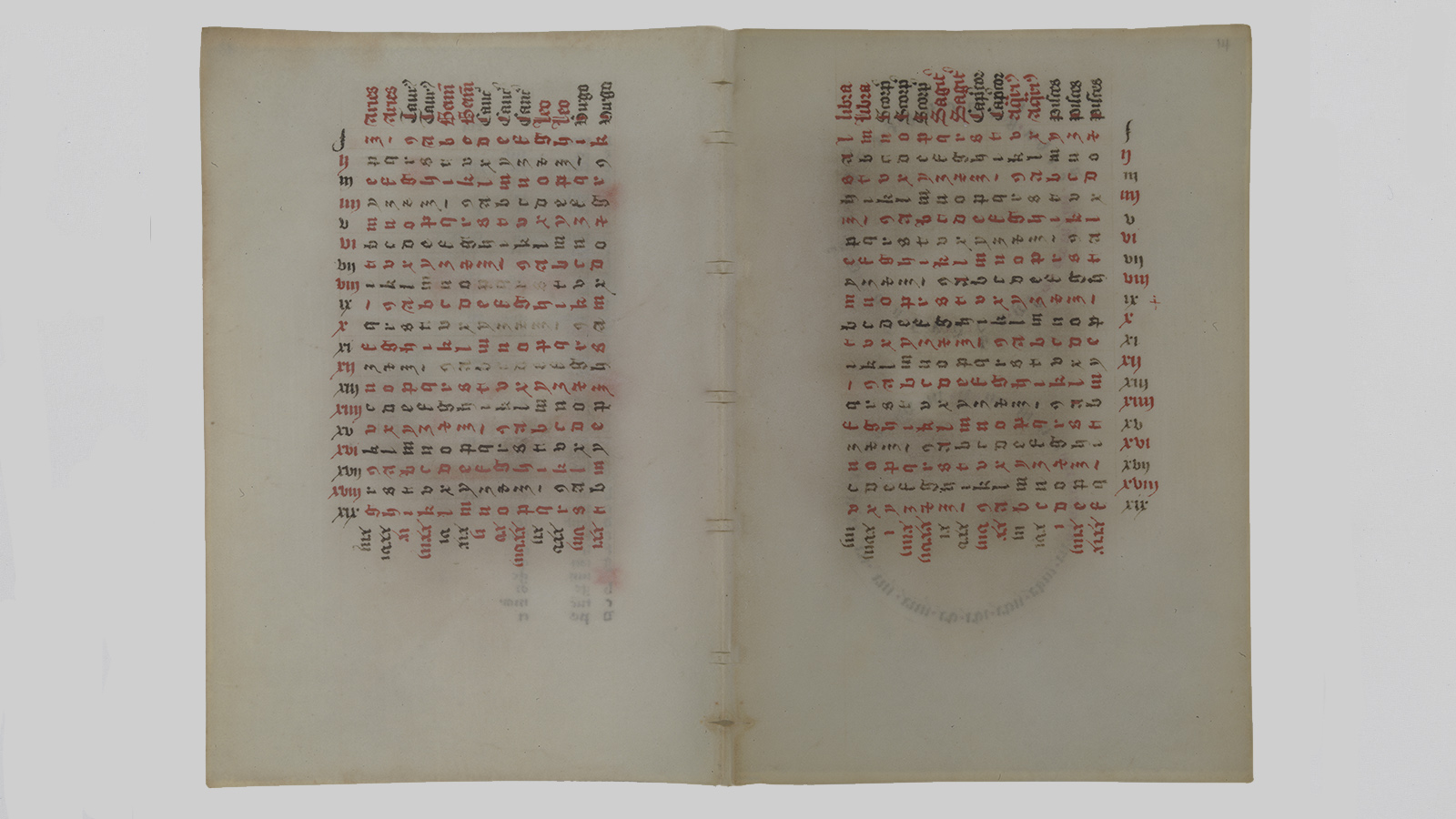

As a rule, these books start with a calendar, which usually includes illuminations for the different months and zodiac signs (fig. 4). In some cases, this section is accompanied by instruments (tables or circles) for calculating liturgical dates and festivities, such as Easter (fig. 5).

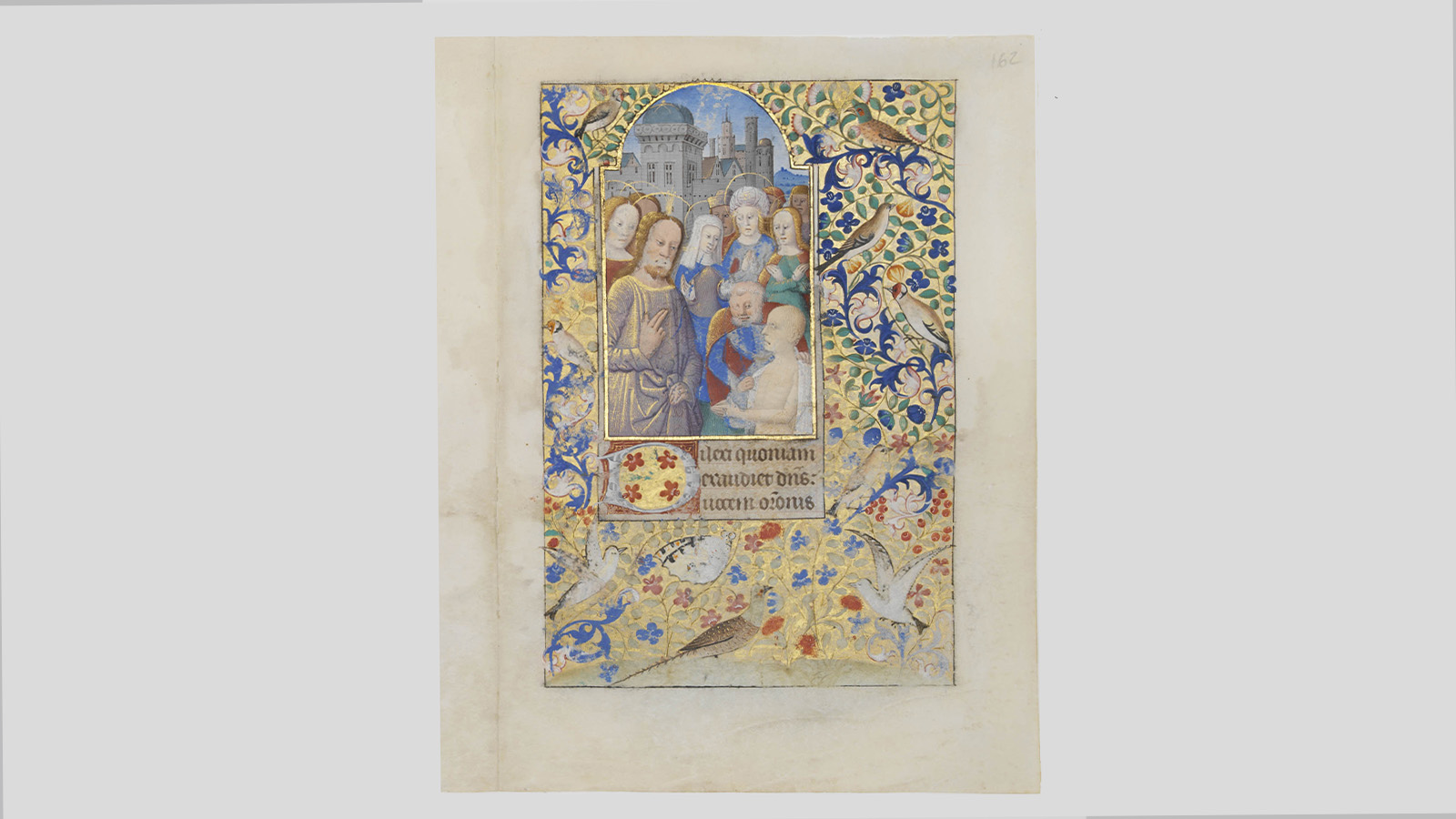

The representation of the destinatary of the book, often depicted kneeling in prayer before devotional figures, for example the Virgin and Child (fig. 6, 7 and 8), in some cases precedes the Offices or Hours, groups of prayers dedicated to the Virgin, the Holy Spirit, the Cross, the saints, the dead, among others. These groups can contain up to eight prayers, according to the time of day and with different levels of importance: Matins (dawn), Lauds (morning), Prime, Terce, Sext, Nones (small prayers said between morning and afternoon), Vespers (afternoon) and Compline (evening).

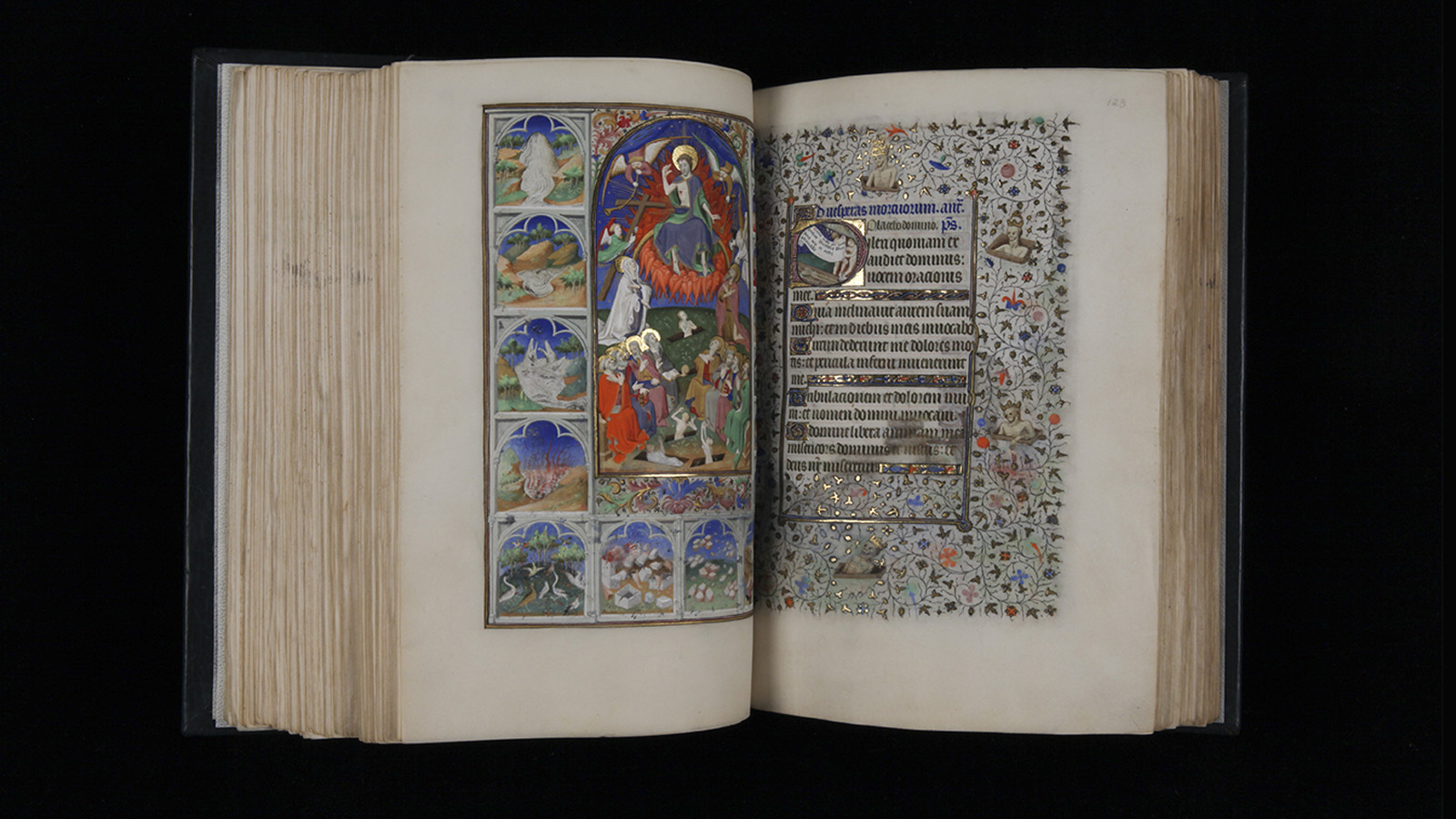

In the case of the Office of the Virgin, the inclusion of illuminations based on the narrative cycle of the Infancy of Christ (Annunciation, Visitation, Nativity, Annunciation to the Shepherds, Adoration of the Magi, Presentation of Jesus in the Temple, Flight into Egypt, Coronation of the Virgin) as an introduction to each prayer is frequent, but not always observed (fig. 9 and 10). The Office of the Dead is frequently illustrated with iconography related to the representation of deceased people, for example the Resurrection (fig. 11) or the Last Judgement, among others.