Calouste Gulbenkian: Collector of Gems

As Jeffrey Spier notes in his catalogue on Calouste S. Gulbenkian’s gem collection, the collector benefited greatly from the British tradition, which prompted the creation of important gem collections by the aristocracy and by a group of ‘educated gentlemen’ from the 18th century in particular.

The desire to reconstruct models from classical antiquity, including the use of artistic prototypes in which architecture is the most prominent form of expression – see the villas, public buildings and palaces in the Neoclassical style that fill the English countryside and the urban fabric of cities like London –, was combined with a taste for the arts and techniques of that world, in which the heroic and the divine intersected.

The early days of Gulbenkian’s collectionism bring us gems that, like the Greek coins, signal the Classicism present in many parts of his collection.

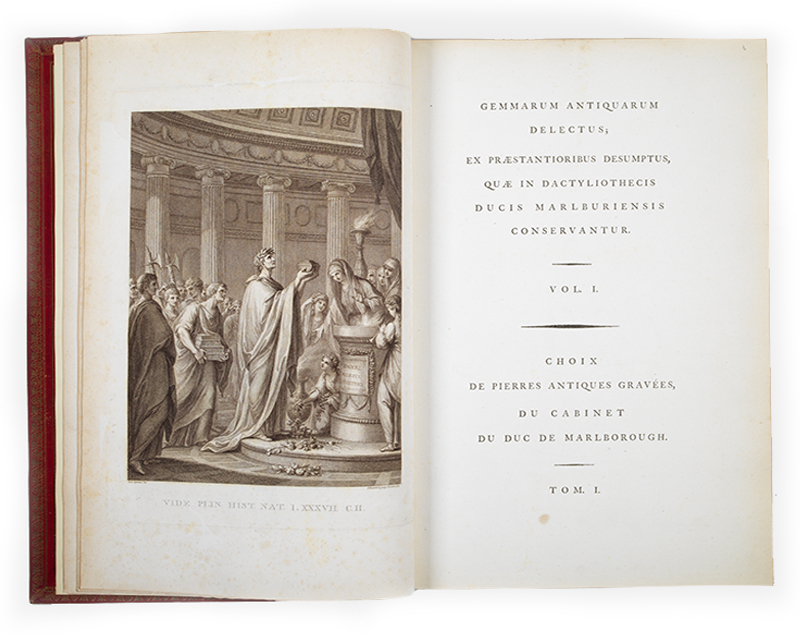

Upon setting up residence in England in the late 19th century, Gulbenkian gained access to the sales of important collections on the London market. In 1898, his collection was swelled by a set of thirty gems from the Alfred Morrison Collection, a textile millionaire and lover of Persian carpets, Chinese porcelain, illuminated manuscripts, and, of course, precious gems. Gulbenkian continued his purchases in 1909, 1920, 1921 and 1925, incorporating items that once belonged to the Duke of Marlborough, Horace Walpole and Francis Cook, among others, taking advantage of the dissolution of the collections upon their owners’ deaths.

Although little correspondence regarding this part of the collection remains, it is possible to identify Gulbenkian’s method through his contact with Armenian brokers such as Gudenian, who tended to negotiate carpets, Feuardent, who mediated in the purchase of gems from the Talbot Ready Collection, and Jacob Hirsch, who was responsible for purchasing the items from the Cook Collection and was one of the main coin suppliers.

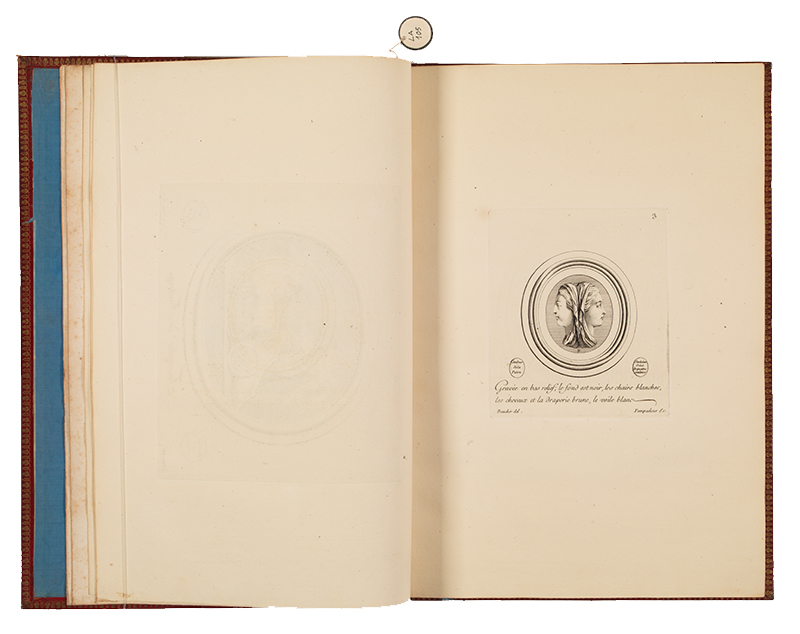

It is also possible to find relevant catalogues from the collections, engraved with prints that expand the iconographic narrative of the minuscule gems (Catalogue of the Duke of Marlborough Collection), Mariette’s treaty on engraved gems and the invaluable inventory of the King of France’s collection with illustrations engraved by Madame de Pompadour.

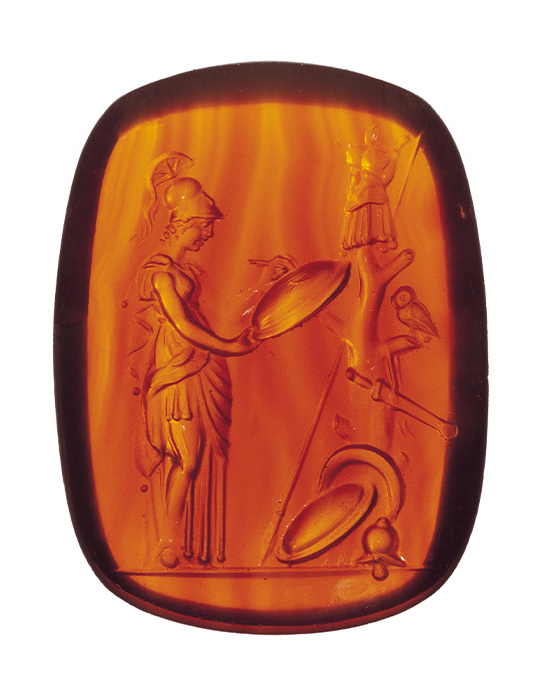

Omphale, Queen of Lydia in Asia Minor, bears the attributes of Heracles (Hercules): the Nemean lion skin and olive wood mace. The story goes that Heracles was punished for the death of Iphitos, one of the Argonauts, and the Oracle of Delphi ordained that he should be enslaved for one year by the beautiful Lydia. The hero's humiliation at being subjugated by a woman was turned on its head when Lydia fell in love with her slave, freeing him and taking him as her husband.

At the same time as he was acquiring Ancient Greek and Roman gems, Gulbenkian was also purchasing Neoclassical gems, jewels by René Lalique and luxurious 18th-century gold and enamel boxes.

His attention was caught by the materials, such as black jasper, amethyst, cornelian, citrine and rock crystal, sculpted in miniature and often assembled in such a way as to transform the gems into jewels. With their exquisite simplicity, the gems were able to hold their own against the creations of Gulbenkian’s contemporary René Lalique and the precious 18th-century gold boxes, all united by the collector’s main objective: the quest for beauty.

João Carvalho Dias

Curator of the Museum