How we can contribute to the health and diversity of tiny creatures in the soil

Gardens for wildlife

Every day, when we go outside, we come into contact with soil. And yet we know very little about this ‘pillar of sustainability of life on earth,’ as it is characterised by Cristina Cruz, Teresa Dias and Silvana Munzi, three scientists from cE3c – the Centre of Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Change, at FCUL, who have been studying this subject for several years.

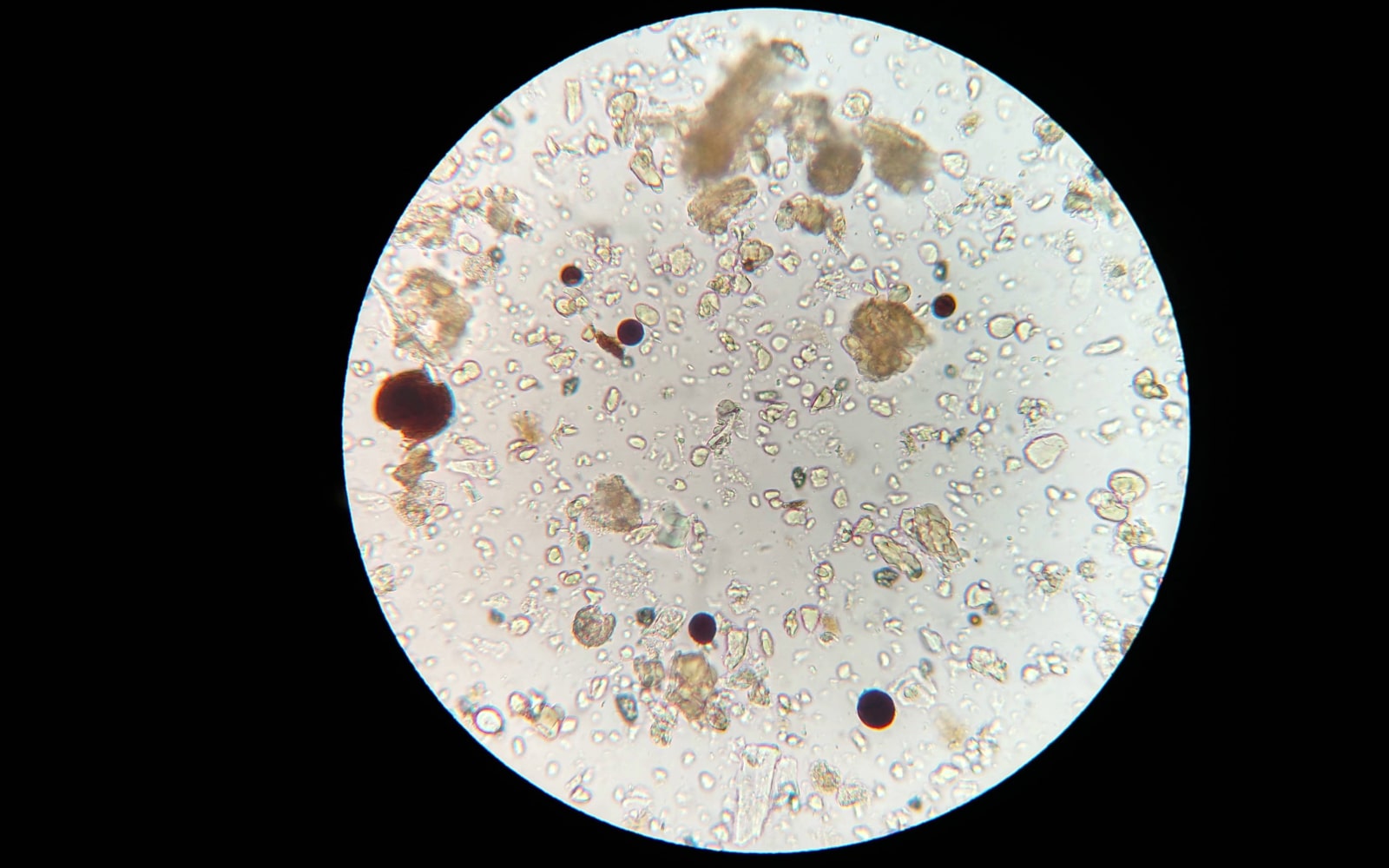

First of all, what is soil? The researchers define it as a complex, dynamic system composed of clay, silt and sand combined with organic matter, water and air, and a hugely diverse range of creatures. It is formed by the erosion of the rock that lies beneath it, through the action of time, as well as of climate, water and countless living organisms. This dark underworld that teems with life, particularly in the upper layer, is home to invisible creatures such as bacteria, fungi, algae and others, as well as some that are already familiar to us, which we can imagine living in the soil, such as plants, ants, earthworms, woodlice, rabbits, partridges and even moles.

We can also think of the soil as a ‘magic carpet’ that purifies air and water, captures carbon, transforms matter and helps foods grow. ‘This magical soil gives us food security, prevents migration and promotes peace,’ the researchers explain.

On the other hand, the soil is also ‘a vast reservoir of the earth’s biodiversity.’ In it live more than half of all known species, including ‘90% of fungi, 85% of plants and more than 50% of bacteria, making it the most species-rich habitat in the world.’

All these creatures, from micro-organisms to those that are visible without the aid of a microscope, play ‘crucial roles in the soil ecosystem,’ as they ‘contribute to fertility and aeration and even help recycle nutrients.’ Many are also vital for carbon fixation and thus play a fundamental role in fighting climate change. Despite this, the vast majority of these organisms have yet to be described: ‘So far, we have only been able to name around 1% of what lives in the soil,’ the researchers reveal.

Bacteria, fungi and algae

Of all these creatures, bacteria are the most abundant in our soil. Formed of a single cell, they appeared in the world billions of years before any other living beings, and they can be spherical, rod-like or spiral in shape. ‘Their metabolisms defy the imagination, they are so diverse! This metabolic diversity means they can adapt to very different environments, and is one of the reasons why we find bacteria in every environment on the planet, from thermal springs and deep oceans to the atmosphere or Arctic snow.’

On the other hand, these microscopic beings provide important services. For example, there are bacteria that become attached to plant roots and help them fix nitrogen, an essential nutrient for plant growth and for all living organisms. Others aid the decomposition of complex organic matter into simpler or inorganic matter, regardless of their proximity to plant roots.

Fungi, ‘a highly diverse group of organisms that cover a broad range of life forms,’ are equally crucial to biodiversity and soil health. In the case of soil fungi, we usually see only the mushrooms, a small visible part linked to reproduction. And yet, beneath the ground, these living beings with their own kingdom – the Fungi kingdom – have another fundamental part: the mycelium, which is formed of very fine filaments called hyphae that create a web that connects, supports or interacts with all the creatures in the soil. ‘Many fungi are important for the decomposition of trunks, roots and other dead matter, for the nutrition and protection of plants and even to regulate populations of bacteria, nematodes and others,’ the team explains.

Algae, which we tend to see in lakes and ponds, also exist in the soil, where they are valuable creatures. Almost always invisible to the naked eye on their own, we see them when they form soil crusts – algae mats – or lichens, which are composites of algae and fungi. ‘These structures are essential in the initial stages of soil formation, where they act as primary producers, in other words, as carbon fixers.’

This carpet on which we tread every day is also home to other creatures such as viruses and protists, which include amoebas and ciliates. These are fascinating groups, but, as yet, even less studied and known.

Nematodes, mites and springtails

Among many other creatures living in the soil, we find the most abundant ‘animals’ on earth: nematodes, whose name means ‘thread-like’ – a good description of their thin and unsegmented body shape. Measuring only millimetres, and omnipresent in aquatic sediments, glaciers and soils all around the world, they represent ‘around 80% of all animals on earth.’ Nowadays, scientists identify different communities of nematodes as a means of measuring soil quality.

Similarly, mites are extremely small, growing to a size of two millimetres at most. Forming a subclass of the arachnid group, they are extremely diverse: more than 20,000 species of mites have been described by scientists, but it is estimated that there are more than 80,000 species still to discover. These minuscule beings are also among the most abundant in soil ecosystems, where there can be as many as 100,000 per square metre.

Like mites, springtails (under the classification Collembola) are microarthropods. ‘They are only a few millimetres in size and are commonly known as springtails because of a forked jumping organ called a furcula, which helps them leap to avoid predators.’

Many of these creatures, from those that cannot be seen with the naked eye to those a few millimetres long, are related to the plants and animals we find on the surface. Parasites are an example of this. But they are also related to each other, in a vast food chain that contributes to the formation of more soil. Many mites and springtails in the soil are known for ‘grazing’ on fungi – fungivores – stimulating the growth and activity of the latter and the recycling of nutrients, thus enhancing decomposition of the plant litter layer. Bacteria, which sit at the base of the food chain, are an important foodstuff for many nematodes, which in turn are ‘hunted’ by many species of mites, which provide food for many birds and species on which birds prey. These birds and their prey are at the top of this food chain and serve as an important indicator of soil quality, as the three researchers explain.

And finally, the ecosystem engineers

Among the many invertebrate inhabitants of the soil, we also find beetles, ants and termites – the latter more common in the tropics – and even earthworms. They all play a role in the maintenance and health of this magic carpet beneath our feet. Ants, for example, are important predators, while termites help digest plant cellulose and recycle organic nutrients.

As for earthworms, like termites and ants, they are known as the ‘ecosystem engineers’ in the soil. The presence of these annelids is often associated with fertile soil for agriculture. Many of them contribute to transforming vegetable matter into earth, feeding off dried leaves and other detritus or carrying them to lower layers, through the tunnels they dig.

What we can do…

How can we contribute to the conservation of these vast and highly diverse communities? Cristina Cruz, Teresa Dias and Silvana Munzi offer some advice that we can all apply to the management of our green spaces:

….and the political measures that can be adopted

There are also various measures that depend on local authority or government:

Gardens for wildlife

Throughout the year, the Gulbenkian Garden is promoting a series of visits focused on how to make our gardens, parks and land, both inside and outside cities, more welcoming for wildlife – fundamental for life on Earth! Wilder magazine follows these visits and publishes articles on each of the different topis covered in partnership with the Gulbenkian Foundation.