Encounters with António Dacosta

When I completed my degree in Modern and Contemporary History, I was sure that my path would lead me to History of Art. I obsessively pondered the questions left open by Heidegger in The Origin of the Work of Art, fascinated by the work that opens up and establishes a world: ‘By the opening of a world, all things gain their lingering and hastening, their distance and proximity, their breadth and their limits.’1

I had the pleasure of meeting António Dacosta in the first year of my master’s at the Faculty of Social and Human Sciences of the Universidade Nova de Lisboa. Rui Mário Gonçalves’ book, published by the Imprensa Nacional – Casa da Moeda, in 1984, and my studies at the time, which focused on Portuguese surrealism, left me with an avid and thirsty mind. Thus, I decided that my dissertation would be about Dacosta’s pictorial work, about the encounters and misencounters of an artist who had stopped painting for almost 30 years and who, therefore, had lived two lives.

However, the vicissitudes of life did not provide a happy ending to this first encounter. I finished my master’s thesis, years later, about films from the 1970s by Portuguese artists, as I mentioned in a previous text.

But as life, it is true, has many twists and turns, António Dacosta came back to me in the middle of 2010, when the CAM, under the management of Isabel Carlos, decided to carry out extensive research on this prolific artist for his centenary exhibition, which took place in 2014, together with the launch of the first digital catalogue raisonné dedicated to a Portuguese painter. It was in this re-encounter that, for several years, I could dedicate myself, with a small team, to the collection, systematisation and study of Dacosta’s work.

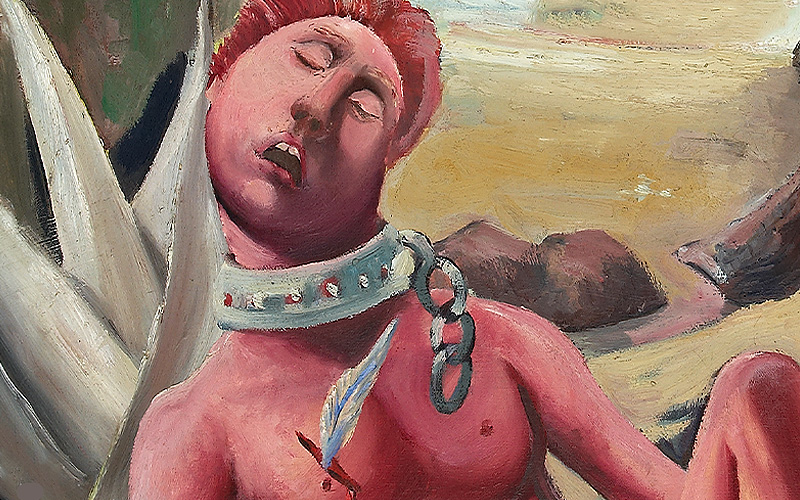

Serenata Açoreana [Azorean Serenade] (1940, attributed date) emerged in a very particular context:

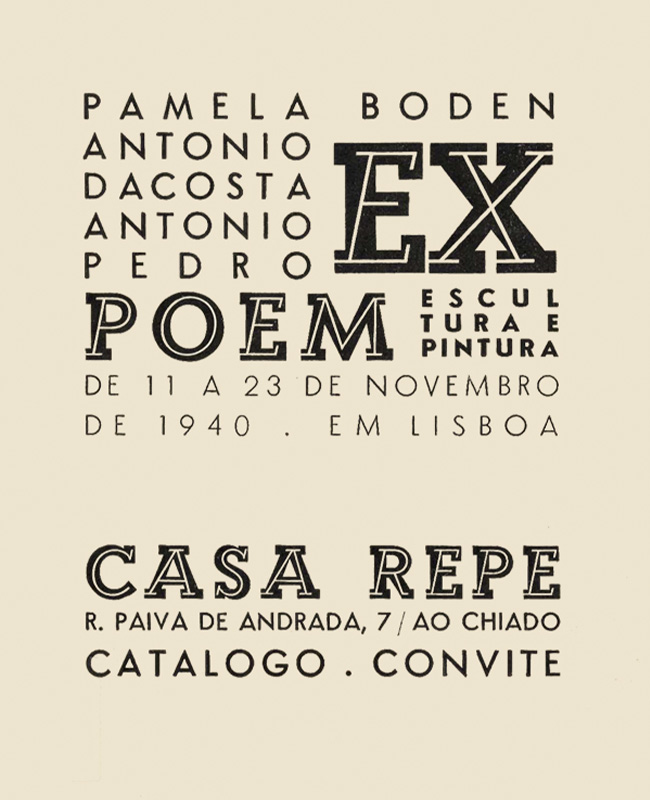

(1) it was part of the first exhibition of an entirely surrealist nature in Portugal, presented under the graphic rubric EX POEM, in Casa Repe, in Lisbon, from 11 to 23 November 1940, the year in which the young Dacosta, at 26 years old, concluded the special course in painting at the School of Fine Arts in Lisbon, after spending the summer at the house of António Pedro in Moledo, in the Minho, near the border with Spain. While there, he was moved by the refugees persecuted by the Franco Regime, in the Spanish Civil War, which would clearly leave its mark on Portuguese surrealism and the paintings produced for this exhibition.

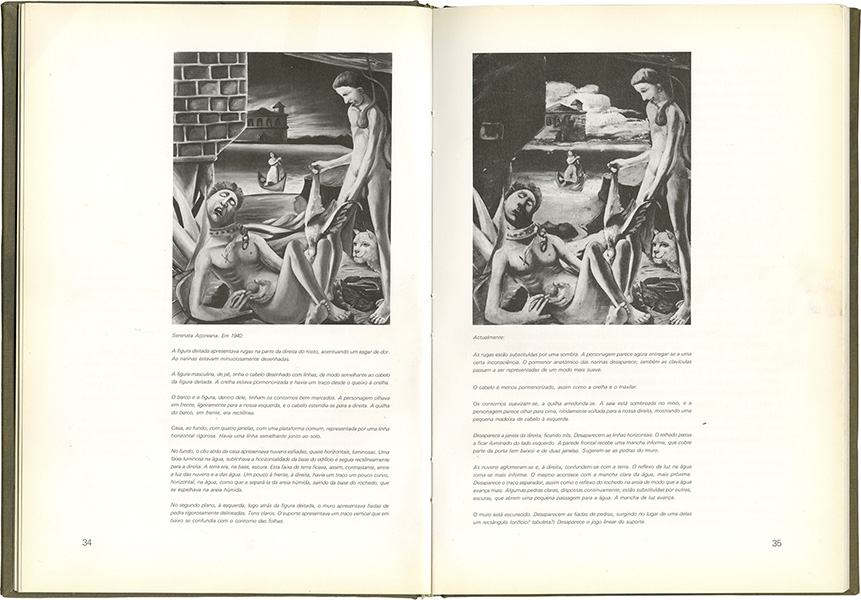

(2) Serenata Açoreana featured on the cover of Rui Mário Gonçalves’ book, mentioned previously, which includes a curious analysis of the retouch carried out by the artist, at the beginning of 1941, which darkened and intensified it.

(3) It was also chosen as one of the 100 Works from the CAM Collection, a publication from 2010 to which I contributed a text about the painting.

The encounters continue and, shortly, a new platform of the raisonné of the work of António Dacosta will be made available to the public so that we do not forget that, as the artist himself wrote:

‘A painting has its twists and turns

Going beyond its margins is almost a ritual act

No mistakes. One needs to look, forget and hope.’2

Patrícia Rosas

Curator of the Museum

- Martin Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’ in Off the Beaten Track, edited and translated by Julian Young and Kenneth Haynes, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2002 [1950], p. 23.

- António Dacosta, ‘O Pintor Mário Eloy’, in Panorama, no. 20, April 1944.

Curators’ Choices

The curators of the CAM reflect on a selection of works, which include creations by national and international artists.

More choices