Part II: Lisbon (March 2023)

Helena de Freitas

Five years after the initial presentation in 2018, at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation’s Delegation in France, Rui Chafes and Alberto Giacometti are being exhibited together again at the Foundation’s head office in Lisbon, united by the same words, Gris, Vide, Cris, in a larger, different space, and with additional works.

The time that has elapsed between these two moments has allowed us to incorporate the history of this encounter that, in truth, has expanded, in time and in geography, beyond the limits previously envisaged.

In 2018, in the institutional space of a Haussmannian building, Rui Chafes used his own sculptures to receive Alberto Giacometti, allowing us a first view of the Swiss sculptor’s works. In 2020, that gaze was symbolically returned in Stampa, Switzerland; Giacometti now welcomed, on his own familiar artistic turf, a powerful sculpture by Rui Chafes, Occhi che non dormono [Eyes that do not sleep], descended from La Nuit [The Night], which was presented in Paris and will always allude to the landscape in which Giacometti was born and worked.

The exhibition presented in 2023 includes the images and memory of these two earlier events and allows us to add a space of reflection.

Although aware of being in an entirely different museum space, with a specific architectural project and with new works, it is important to convey the essential aspects of that first experience that was simultaneously intellectual and physical.

In 2018, Rui Chafes guided us along a path from which we could not exit indifferently. The exhibition was entered through the inside of a sculpture (Au-delà des Yeux [Beyond the Eyes], from 2018), a space that opened into darkness, via an indecipherable and unpredictable route ill-suited to speed or hurry, instead demanding time for adaptation and revelation. Vagar [slowness] was therefore one of the three words that it seemed appropriate to add to the lexicon that links the two sculptors. Here we find an immediate statement of rupture, not just in terms of the visitor’s spatial relationship with the work, which is inverted, moving from the passive status of external observer to forming a body with it, but also in their necessarily slower temporal relationship.

The path that leads us to view Giacometti’s works through the inside of two of Chafes’s sculptures is not an easy one, travelling through a constricted space, echoing the exasperating process that tormented the Swiss artist for years as he attempted to represent what he saw. And this brings us back to one of the fundamental aspects of the construction of this project: vision. But for us to receive that experience of vision and revelation, we must enter a sensitive space, where emotion is possible. We face the darkness, the imbalance and the unknown, we hear the sound of footsteps, we can sense the smell of iron and the contrast of scales, we can touch the sculpture, or at least feel it like a wrapper or skin, which introduces a sensory dimension to this otherwise strictly formal experience. And indeed, this can be found in the senses present in its title: Gris, Vide, Cris.

The body, in its infinite possibilities, is the centre of the exhibition, the bodies created, the bodies of visitors, and the space that exists between them.

We know that the formal analogies between the two artists are irrelevant. In truth, the comparative protocol between the sculptors, or the model of duality itself (two artists, one dialogue) is eventually superseded. Beyond the two names, or the formal distance between the objects on display (and we have known for a long time that neither sculptor makes objects), what we are given to experience is a force field, permeated by the resonance of the works,6 as well as by that immaterial energy that, in many inverse ways, both artists pursued and in which they ended up meeting.

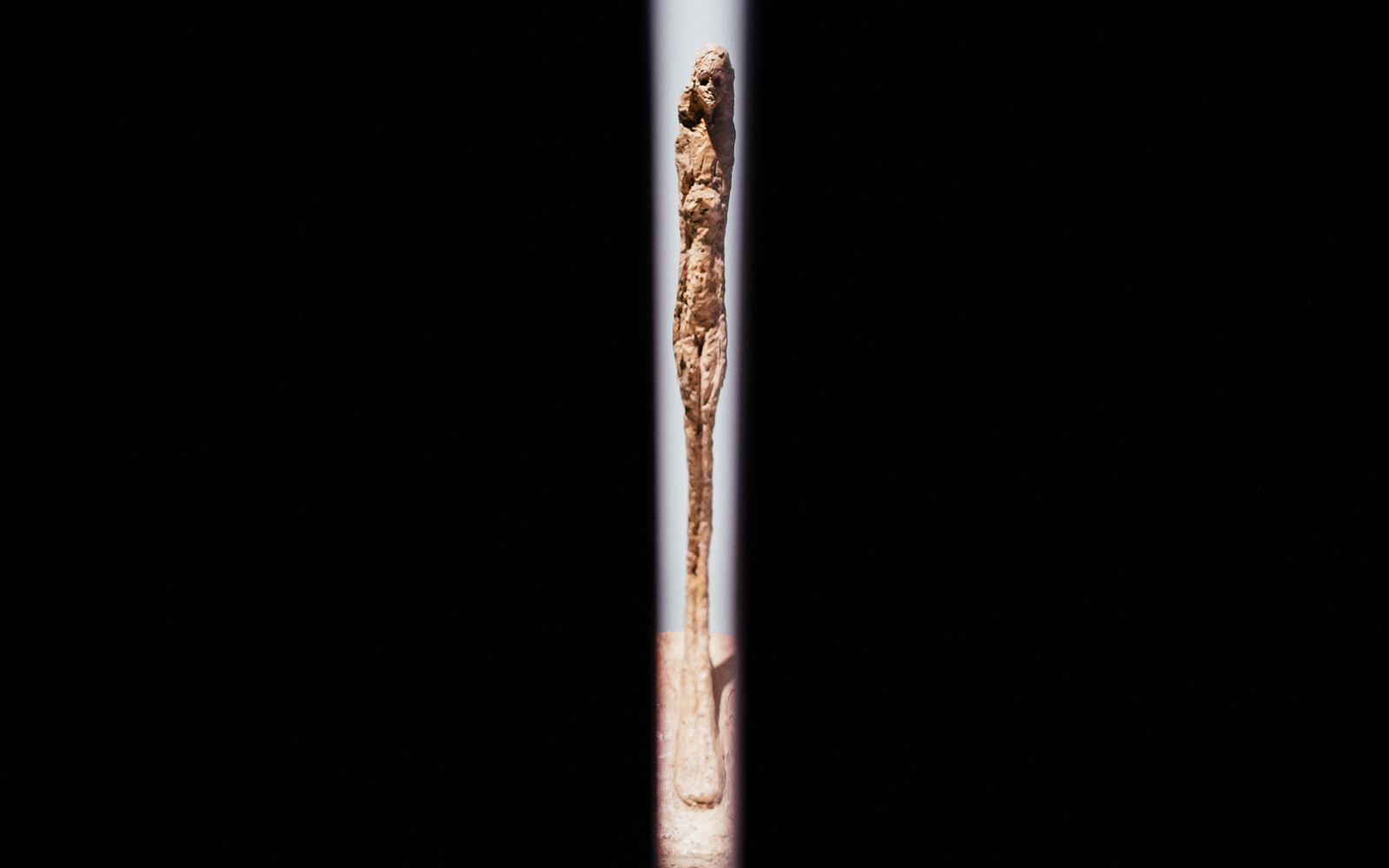

In total, the Lisbon exhibition adds ten works to the first edition. The immense generosity of the Fondation Giacometti in Paris has allowed us not just to keep all the most essential sculptures in the exhibition, but also to add a further four, which make this version even denser and its web of relationships more complex. The new works on display pose challenges, imposing themselves in the space with a very different materiality from the first sculptures chosen, more vulnerable and with less physical substance. They are medium-sized figures, heavy and majestic.

A new series by Rui Chafes picks up some paths and advances further along others, but in all the works created for this new encounter we find a way of deepening and radicalising the points of tension, as well as a play of oxymorons between past and present. Some of these sculptures (Nada existe [Nothing exists]) are a continuation of earlier forms. On the reverse of these abandoned, suspended bodies, where for the first time the artist rips through the silky skin of his sculptures to allow us to glimpse the roughness and scars of their construction, we find the first marks of this sculptural encounter.

Tu nem sequer me vês [You don’t even see me], from 2021, is a more recent sculpture, a defensive and vigilant body, made to live on a diagonal or on a corner, as an excrescent mass. A sculpture-gargoyle, it fulfils its historical function in the space, defending, dramatising, and draining. This gargouille (throat) seems to contain, in the powerful architecture of its elevated forms, another configuration of shouts or muffled, scattered sounds. It is as different as it could be to the exuberant and expansive form of the dying breath of La Nuit, and in symphony with the image of Giacometti’s bodies, silent, heavy, and significant, on the solid bases that hold them.

It is undoubtedly by questioning this integral element of the Swiss sculptor’s works that Rui Chafes develops his most recent sculptures, Aprendemos a esquecer I and II [We learn to forget I and II], from 2021, on structures that we could call ‘planes of support’ or ‘planes of suspension.’ Supported on these iron plates, as fine as leaves and precisely outlined (at a specific angle), these sculptures, far from holding on to the ground, are thrown skywards, erecting themselves like broken wings, in a gesture of impossible projection, as though the artist has inverted their function and, in a visual game, suspended on the ground sculptures that should be floating from the ceiling, thus maintaining their imponderable nature.

In this visual challenge, five years later, we thus witness the transformation of the light and its lingering trail. It is unusual to be surprised by an artistic experience that is so intense, which presents in a structural rather than illustrative way, and in exclusive dialogue with the artistic matter, fundamental changes to the aesthetic and ethical paradigm, which today shock the art world. Sustained in a very old conversation that he has been able to continue with his peers (Alberto Giacometti, among others), Rui Chafes keeps alight and in motion the questioning of art and its function in the contemporary world.

In this exhibition, constructed with no rigid script or agenda, we can recognise the intense reverberation of the pulsation of humankind, as we do in each of Alberto Giacometti’s fingerprints.