‘Portugal is no country for women’

The title of this exhibition route – Portugal is no country for women – refers to a remark made by Paula Rego’s father, who encouraged the artist to distance herself from the oppressive conservatism experienced in the country during the Estado Novo dictatorship. Subjugated to a lesser status, deprived of rights and oppressed by a chauvinist and conservative education, women had to withstand a grim social and political context.

In a world where injustice between men and women can still be felt, art plays an increasingly important role in fighting inequality and contributing to the affirmation of female identity.

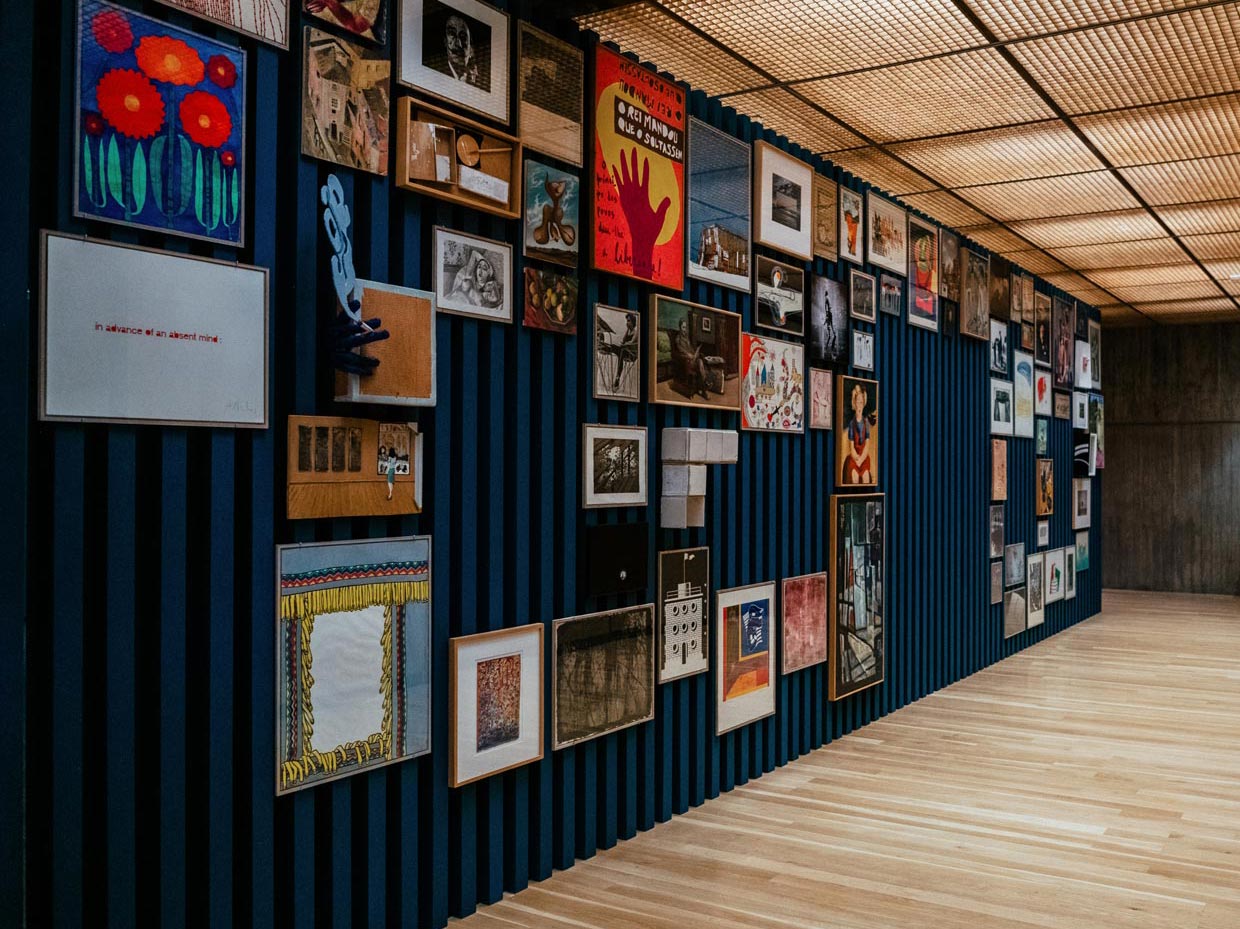

Exhibition Entry / Mural

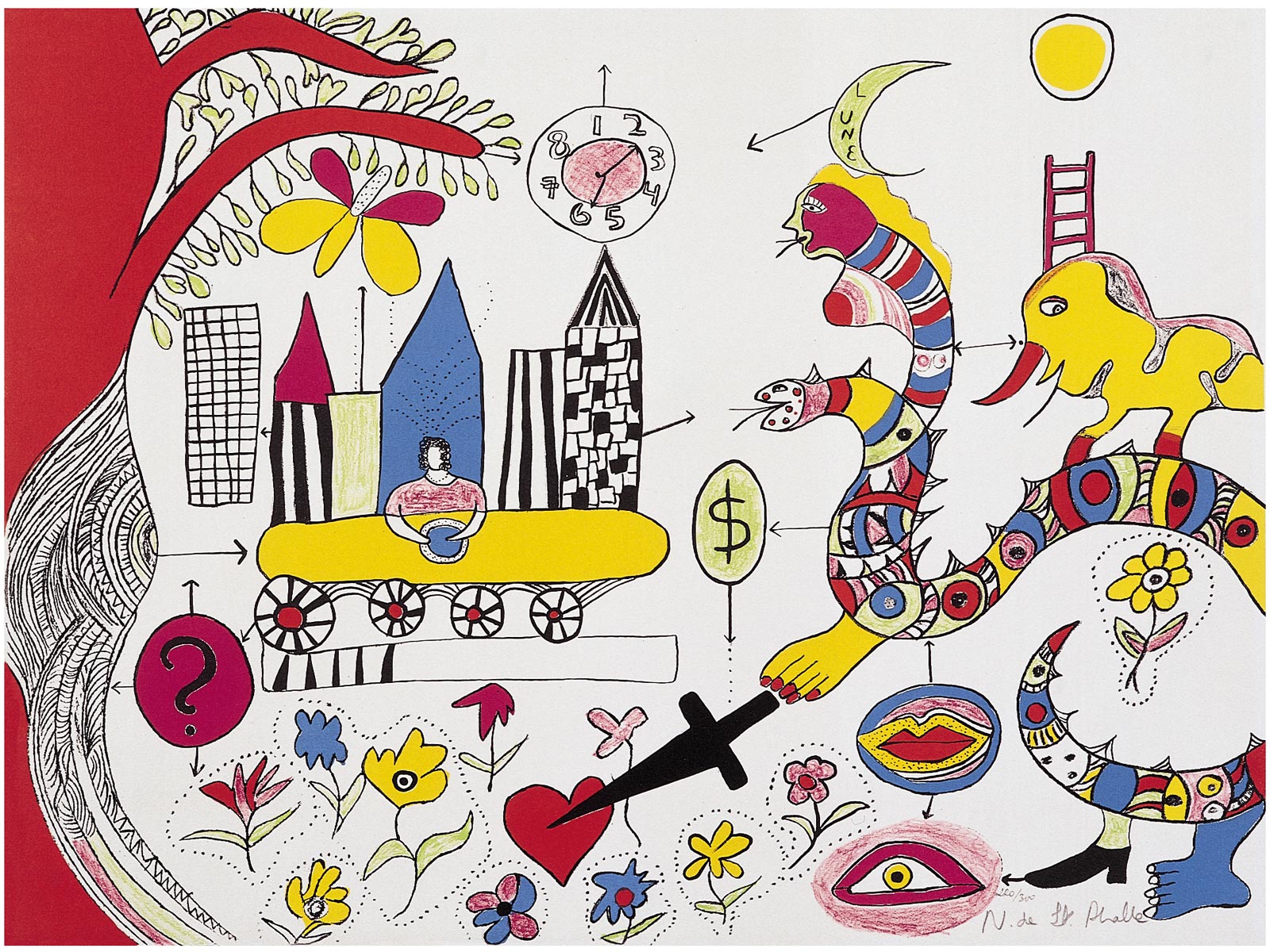

Niki de Saint-Phalle, Rêve de Jeune Fille, 1972

In this artist’s multifaceted work, the feminist ideal is ever-present. Through the use of biographical facts in her works, and focusing on sensitive subjects such as incest, Niki de Saint-Phalle puts forward a criticism of conservative patriarchal society and violence against women.

In the lithograph Rêve de Jeune Fille [Dream of a Young Girl], the artist constructs a figurative world that is dreamlike and strange, with hybrid figures that are somewhere between human and animal.

The snakes threatening the female figure are an allusion to her sexually abusive father, to whom the artist also refers to in the opuscule Mon Secret [My Secret], from 1999. These signs express her inner struggle to overcome traumas to move towards creating a female freedom.

First Acquisitions

Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso, Title unknown (Coty), c. 1917

Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso, a pioneer of Portuguese modernism, took part in the international avant-garde revolutionary movements of the time. During an enforced stay in Portugal, due to World War I, the artist painted one of his most emblematic works, which makes reference to François Coty, creator of the modern perfume industry.

We find an earlier reference to the French parfumier in a letter that Amadeo wrote to Lucie, his wife, in 1913, in which he asks: «So, is Coty’s perfume any good?»

The central theme of this work, however, goes far beyond perfume. The floral elements and fragments in the work – hair clips, a necklace, mirrors and panes of glass – convey the glamour of the fashion industry and the woman’s world in the early-20th century.

They remind us of the growing emancipation of women and their increasingly active role in society, due to the prolonged absence of men, who were away fighting or between wars.

The work also alludes to a theme widely represented throughout the history of art: vanitas. Titian, Velázquez and Rubens had all painted female nudity and its reflection in a mirror. However, Amadeo manages to give this work a unique three-dimensional aspect, involving the observer and subverting their position as a voyeur, at the same time reflecting on the beauty of modernity. It is the unexpected hubbub of a still life.

The Beggining

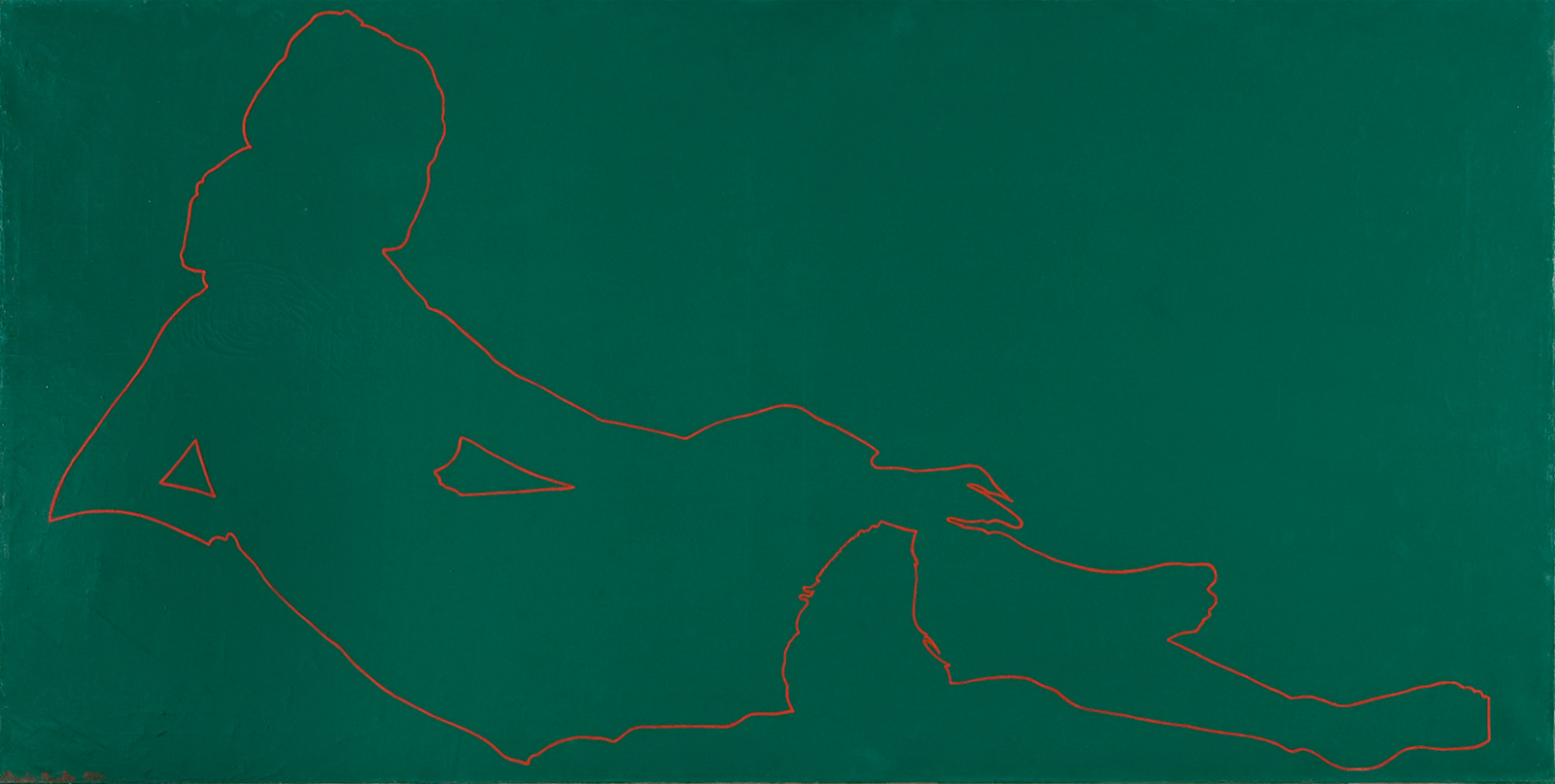

Lourdes Castro, Odalisque d’Après Ingres, 1964

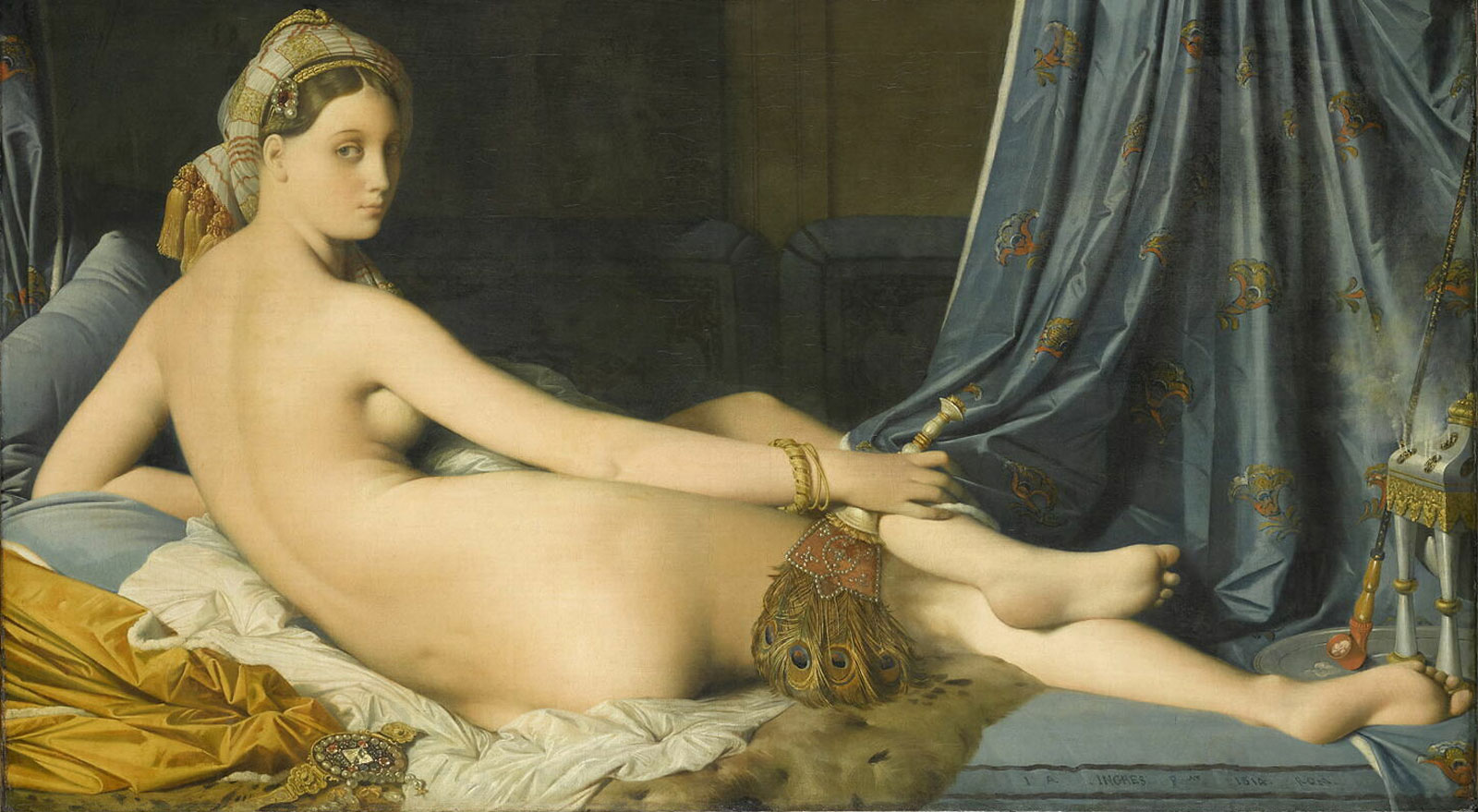

Through Odalisque d’Après Ingres, Lourdes Castro cites and pays homage to a renowned name in French painting: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. During her time in Paris (1957-1983), the artist frequently visited the Louvre to see his painting.

Odalisque d’Après Ingres opens the door to a never-ending process of experimentation based on the exploration of shadow. The painting in question breaks down Ingres’ work, transforming it into the simple outline of a silhouette that negates the voyeuristic nature of the original. The artist removes the exotic references from the work, retaining only the curved feminine contours of the body, which allows us to immediately associate it with the original painting.

In this work, Lourdes Castro alludes to the countless recreations of enslaved women from an imaginary East created by male artists. Through this representation, she also questions Eurocentric cultural stereotypes, as well as the eroticised and sexually discriminatory standard of female representation throughout the history of art, as the Guerrilla Girls would do some twenty years later.

«We must inaugurate it»

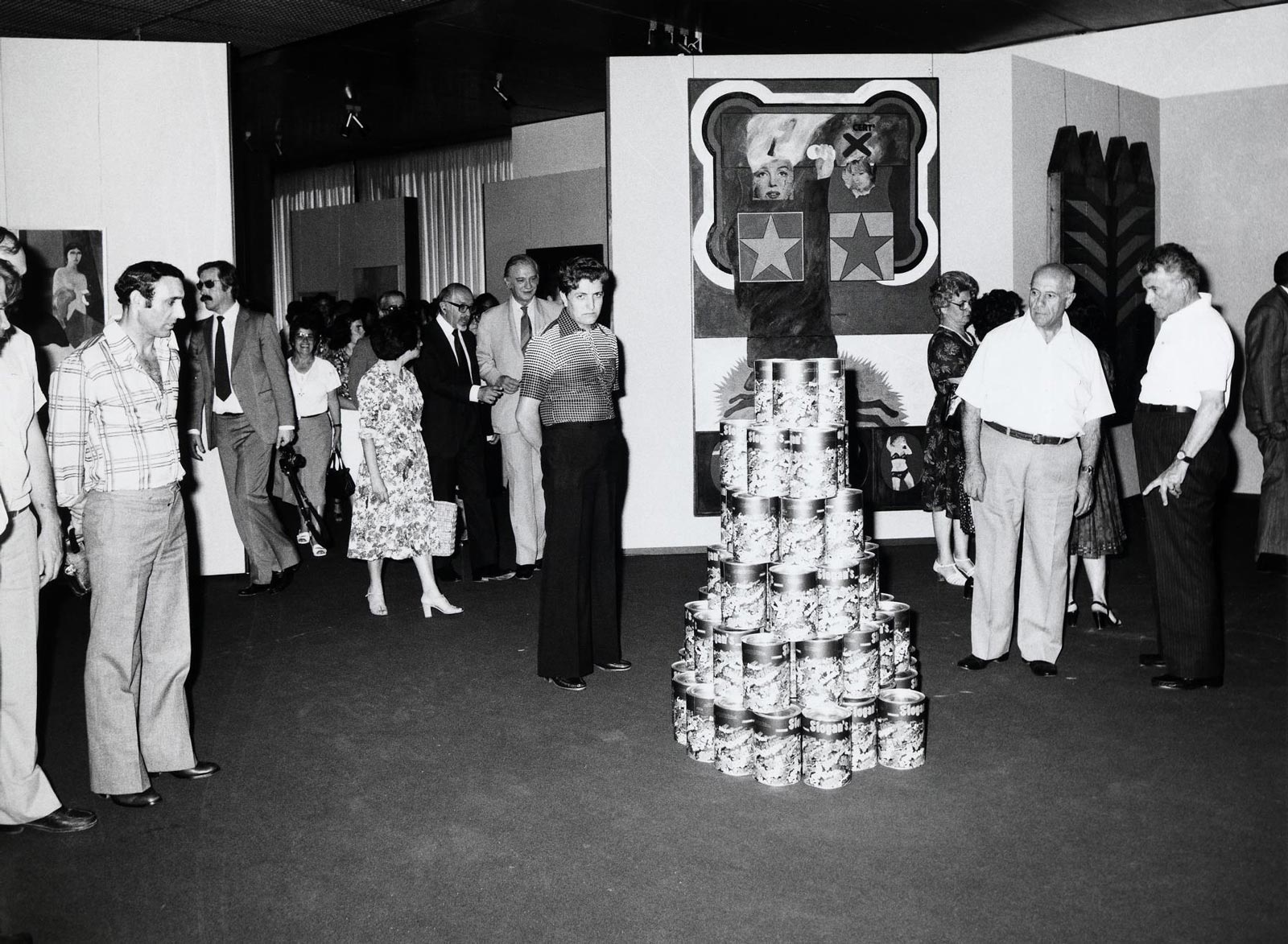

Peter Phillips, For Men Only – Starring MM and BB, 1961

For Men Only – Starring MM and BB is one of the first works created by Peter Phillips, as a young artist.

One of the pioneers of Pop Art, Peter Phillips reveals, in his work, some of the visual transformations that emerged during the 1960s, stemming from the great social, political and cultural changes that were taking place during the postwar period. The artist was strongly influenced by American culture and incorporated the visual languages of advertising and graphic design in his work.

In this painting, he adds photographic representations of the film stars of the 1950s who were regarded as sex symbols, such as Brigitte Bardot and Marilyn Monroe, and photographs of a famous stripper from the period, associating these images with the Victorian board game ‘The Hare and the Tortoise’ – which contains the phrase «she’s a doll.»

Lying somewhere between criticism and humour, the title For Men Only – Starring MM and BB evokes the contribution of the film industry and the ‘star system’ to the creation of stereotypical female sex symbols.

Phillips had great respect for the traditions of western art history and experimented with juxtaposing them with contemporary developments, drawing the image of these two figures inside a schematic frame that recalls religious icons, while the general composition of the work echoes the structure of pre-renaissance woodcuts.

Clara Menéres, O Parto, 1963

Clara Menéres was a neo-vanguard artist whose work focused on gender issues. Her career was marked by a diversity of materials and methods, and she created both installations and traditional statuary.

In the Portuguese art world, prior to the 1974 Revolution, Menéres challenged paradigms by representing the body as a protest against social constructions and the patriarchal model.

The work O Parto [The Birth] was created in 1963, the year that Clara Menéres became a mother for the first time, while still a sculpture student. The female figure in labour is represented in a fragmented and incomplete way, renouncing any idea of classical beauty, symbolising the violence of customs relating to the rights and bodily freedom of women.

Although she used bronze, a canonical material, her decision to represent the experience of childbirth demonstrates her intention to break with the traditional artistic themes that idealised women.

Nikias Skapinakis, Encontro de Natália Correia com Fernanda Botelho e Maria João Pires, 1974

This work rounds off the series Para o estudo da melancolia em Portugal [For the study of melancholy in Portugal], started by Nikias Skapinakis in 1967. With an eye on the events of May 1968 in France and the sense of hope sparked by the ‘Marcelist Spring’ in Portugal, the artist depicts various gatherings of women between the late 60s and early 70s. In the five sociological portraits of which the series is composed, the painter underlines the latent unease during this time of disappointed expectations, of delayed endings, desires and disillusion.

This Encontro [Encounter] depicts three well-known faces from Portuguese society: arms folded and shown in profile, the irreverent Natália Correia, an intellectual with a courageous fighting spirit, a poet and editor, member of the National Assembly, talented public speaker, anti-fascist, feminist and defender of erotic freedom; in the centre, Fernanda Botelho, a satirical writer who was arrested by the PIDE [Secret Police]; and to the right, the only one who dares to meet the observer’s gaze, Maria João Pires, from a younger generation but sharing the same ideals, who already had an international career as a pianist.

Skapinakis, a fan of figuration that came very close to Pop imagery, pays homage in this canvas to a group of women who were contributing to a significant change in their role in Portuguese society. With the April 1974 Revolution and the end of the dictatorship, the painter embarked on a new series entitled Os Caminhos da Liberdade [The Paths of Freedom], in which some of these women were once again protagonists in the history of the freedom for which they had also fought.

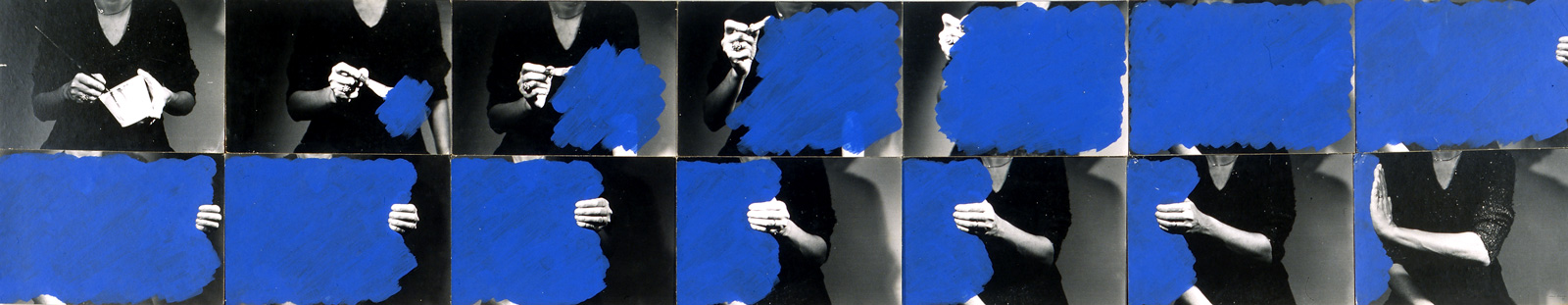

Helena Almeida, Pintura Habitada, 1976

Pintura Habitada [Inhabited Painting] is a work of the vanguard feminism of the 1970s. Helena Almeida was one of the first artists to use self-representation as the main theme of her work, breaking with traditional compositions.

In this work, the large mosaic of images marks an end of rigid typologies, creating a hybrid work through the fusion of photography, painting and performance. The artist experienced her body as an object and as a support for the works, sparking debate on the emancipation and empowerment of the image of women.

Helena Almeida’s self-representation is one of the most striking moments of a new social and political context in Portuguese art and in the affirmation of female creation.

Beyond the Fine Arts

Luísa Correia Pereira, Cristiana, 1994

Inscribed in the recent history of Portuguese art, Luísa Correia Pereira’s oeuvre was rediscovered with the retrospective exhibition Fiat Lux: Paris-Lisboa. Jogos Infantis e Desportos e Jogos [Fiat Lux: Paris-Lisbon. Children’s Games and Sports and Games], which took place at CAM in 2003.

Luísa Correia Pereira lived in France and did not exhibit regularly in Portugal. The artist produced few works, which, along with the fact that she was a woman, can explain her late recognition.

Over four decades, Luísa Correia Pereira produced paintings, drawings and prints that stood out for their singularity and the playful dimension of her approach, uncommon among the artistic practices of her generation.

In her work, we find sparks of a poetic, utopian and fantastical imagination, primitive in nature. Her work is often compared to Art Brut, an expression coined by Jean Dubuffet to define art with a naive expression, free from conventional standards, or to Abstractionism, for its strongly experimental sense.

In Cristiana, the artist’s gesturality manifests itself in a web of dark outlines that contain what appears to be a female figure. The red lines could allude to the blood of a wounded body in metamorphosis – a bird? A fish? The transparency and lightness of the watercolour and the flow of vibrantly coloured lines intensify the outline of this symbiotic being – somewhere between a flying woman and an aquatic woman. The title of the work inscribed on the support suggests that it is of as much significance as any other element of the composition.

Permanent and temporary

Mafalda Santos, 10 cm de Dilatação, 2019

Mafalda Santos’ oeuvre reflects on gender issues. The work on display, the triptych 10 cm de Dilatação [10 cm Dilated], can be read in different ways: on one hand, it is an ode to female creation, through the inscription of names of Portuguese women artists from different generations, often forgotten or ignored; on the other hand, the title of the work also evokes the experience of childbirth, 10 cm being the ideal measure of cervical dilation for a natural birth.

Two moments that symbolise the recovery of historical memory in terms of the female artistic condition, but also the hope of a new future, with full recognition.

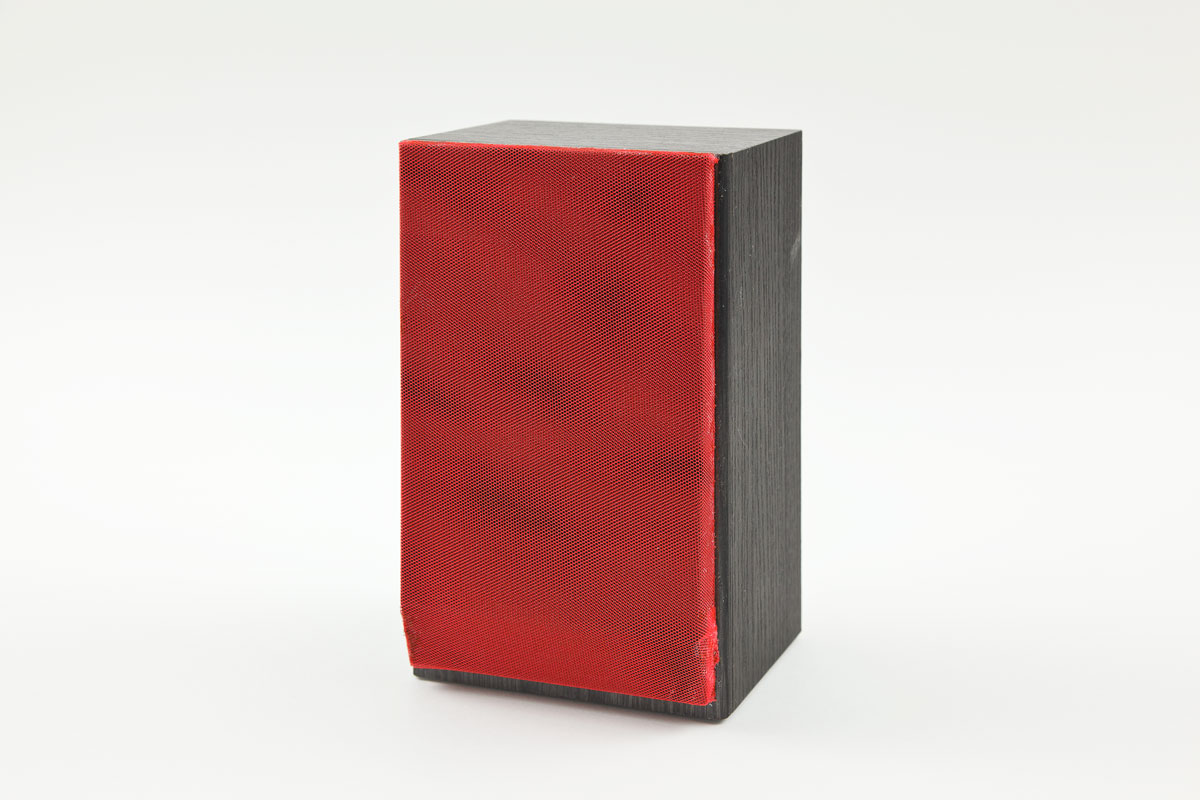

Luísa Cunha, Senhora!, 2010

The work Luísa Cunha has developed involves a performative approach that explores the voice as a sculptural material. The situations she creates are unexpected and ironic, always opting for the minimalist and conceptual route.

In this installation, the artist uses her own voice in an assertive and colloquial fashion to utter the phrase ‘Senhora…! Toda a gente sabe’ [Senhora…! Everyone knows] This phrase is repeated on a loop, with short pauses between each communication, and emphasises the hypothetical revelation of a secret or a denunciation.

The word Senhora is a conventional way to address someone in Portugal, old-fashioned, relating to a married woman, which makes the message intriguing, but also clearer. The blood-red fabric that covers the loudspeaker lends itself to the allegory of something prohibited and erotic, implicit in the words spoken.

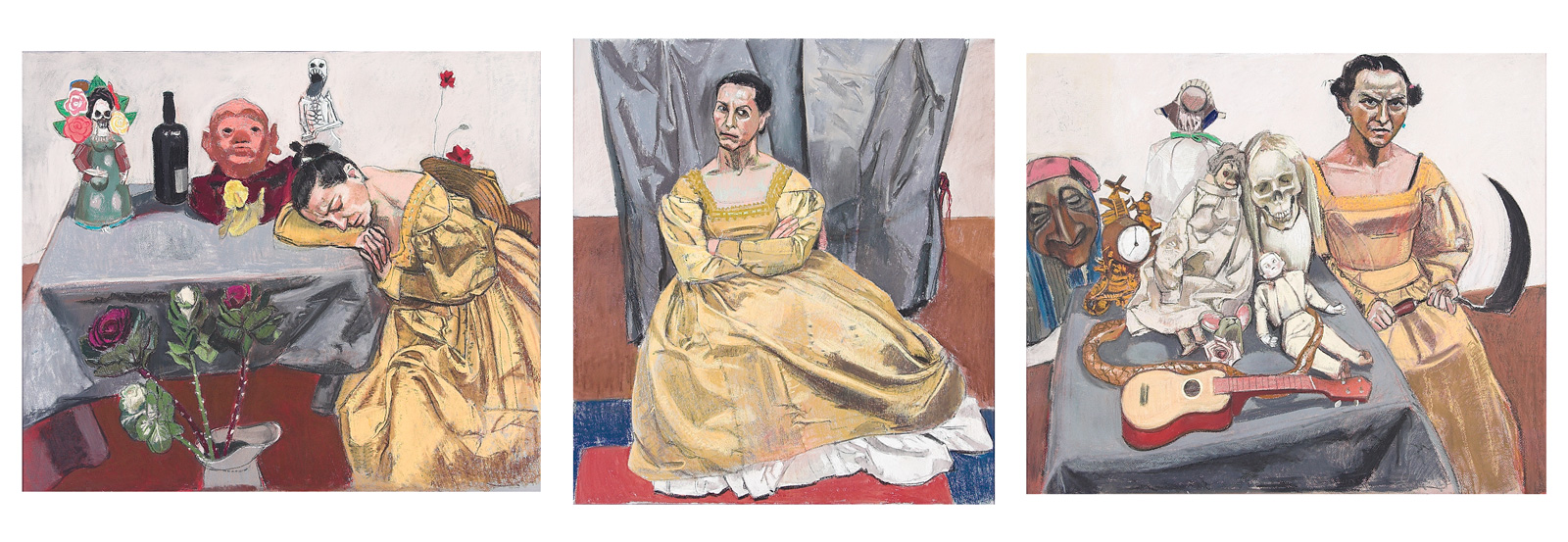

Paula Rego, Vanitas, 2006

This work is the result of a commission by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation to the artist Paula Rego, to commemorate the institution’s fiftieth anniversary. Inspired by the short story Vanitas, 51 Avénue d´Iéna, by Almeida Faria, this triptych was shown to the public for the first time in 2007.

The vanitas are paintings that link the concept of beauty to physical decay, with the staging of objects that symbolise death, futility and the fleeting nature of human life.

In this triptych, the female figure stands out for her sophisticated golden-yellow dress and is represented in three different attitudes towards death: resigned, through the sleeping figure; determined, in the centre; angry, in the figure on the right. Other women represent fundamental worlds in her work: a rag doll with a green ribbon that, in the artist’s words, represents ‘the woman who works hard, who has many children or abortions, who suffers’; or the model Lila, dressed in the colour of the gods, immortalising the creative woman, the artist herself.

In this work, Paula Rego once again turns to her own biography to evoke suffering, fear, betrayal, mourning, depression and the vital energy in the creation of this probable self-portrait as a vanitas. Through it, the artist represents complex and common experiential aspects of female identity.

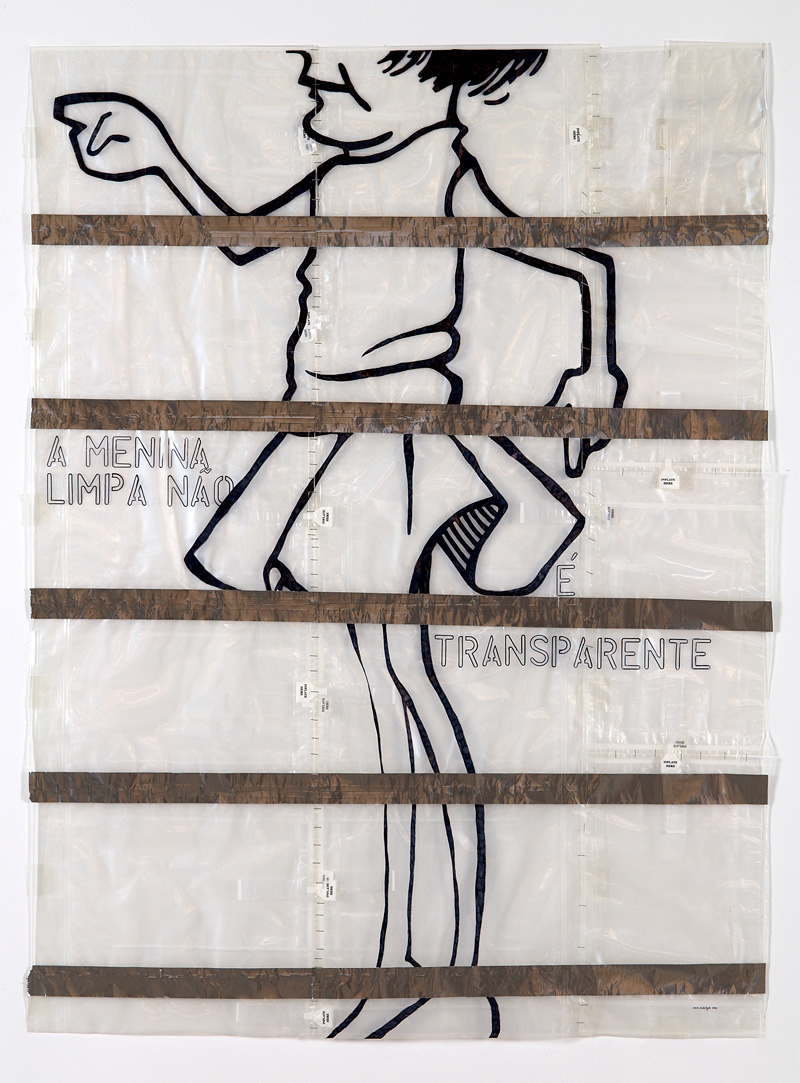

Ana Vidigal, A menina limpa não é transparente, 2000

Ana Vidigal’s work explores the condition of women in society. The artist makes use of diverse materials that she finds in family storage boxes or at flea markets – photographs, letters, magazines, postcards, clothing and toys, among other objects and materials of a domestic nature. Like life itself, her painting is an accumulation of layers, a memory reconstructed in the present.

This work is part of a series entitled Menina Limpa, Menina Suja [Clean Girl, Dirty Girl], a duality that defines the artist herself, referring to her conservative education, in contrast to her rebellious nature. The series presents an ironic play on various phrases in connection with a cartoon female figure, which questions the conservative family model, associated with the woman’s role.

In this composition, the girl’s figure outlined in black against inflatable plastic almost has no head – all we can see is the mouth. Her arms seem to be making a mechanical gesture. The multiple inflation points across the plastic surface – INFLATE HERE – raise the perception of a body that, with a note of irony, can increase in volume. This clean girl that the artist claims is not transparent presumes a confrontation between reality and appearance, between being and seeming, a mask imposed by society that hides and conditions the emotion of living to the full.

Coordination

Emília Tavares

Curators

Catarina Rebelo

Georgia Quintas

Laurinda Marques

Paula Nobre

Rita Cêpa

Sofia Pascoal

Sponsors

Partnership between CAM and Universidade Nova de Lisboa