Homage and Oblivion

In the history of sculpture, there is a celebratory tradition that is arguably as old as art itself. My aim in bringing together this group of works from the CAM collection is to identify the intention of paying homage and that of its opposite, falling into oblivion, on different levels and based on contrasting formulations. Although focused on sculpture, this proposal also looks at painting, photography and prints, particularly in cases where sculpture is used as an object or reference. Only the portrait seems to escape this condition.

The inclusion and consideration of works such as Cutileiro’s Maqueta de Estátua Equestre [Model of Equestrian Statue] illustrates the most common consecrations in statuary, for example, works dedicated to the Unknown Solider or figures from religious iconography.

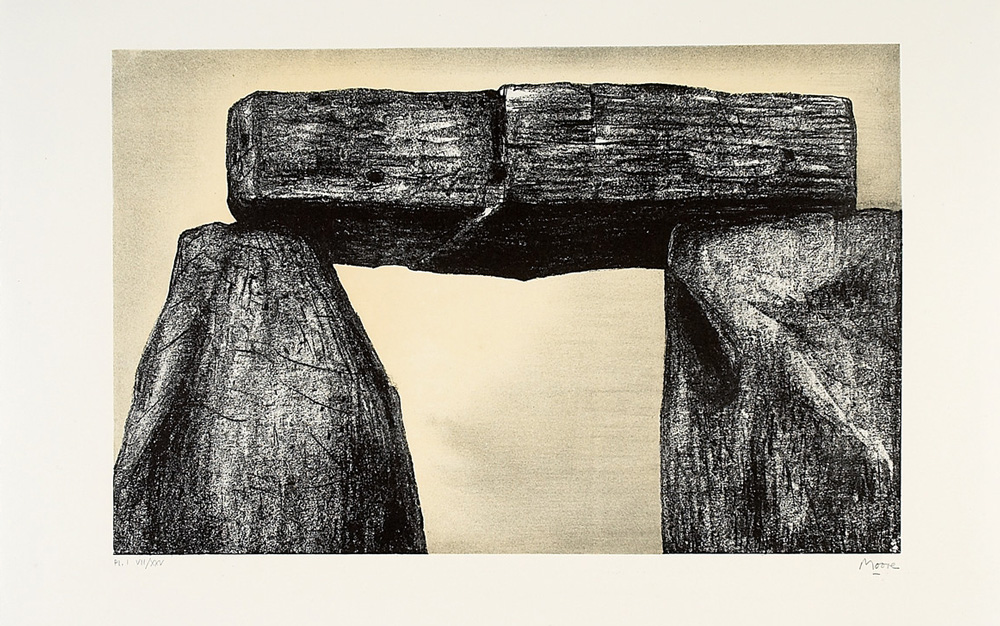

Stonehenge (a series of lithographs by Henry Moore), linked to the veneration of the dead, or the piece by José Pedro Croft, which can also be related to the imaginary realm of the grave, emphasise the ritual side of this preservation of the memory of those who have lived and who came before us in attempting to decipher the world. This is also the case with the painting from the series Porta Estruca [Etruscan Gate], by Graça Pereira Coutinho, which brings an ancestral cultural reference into the present day.

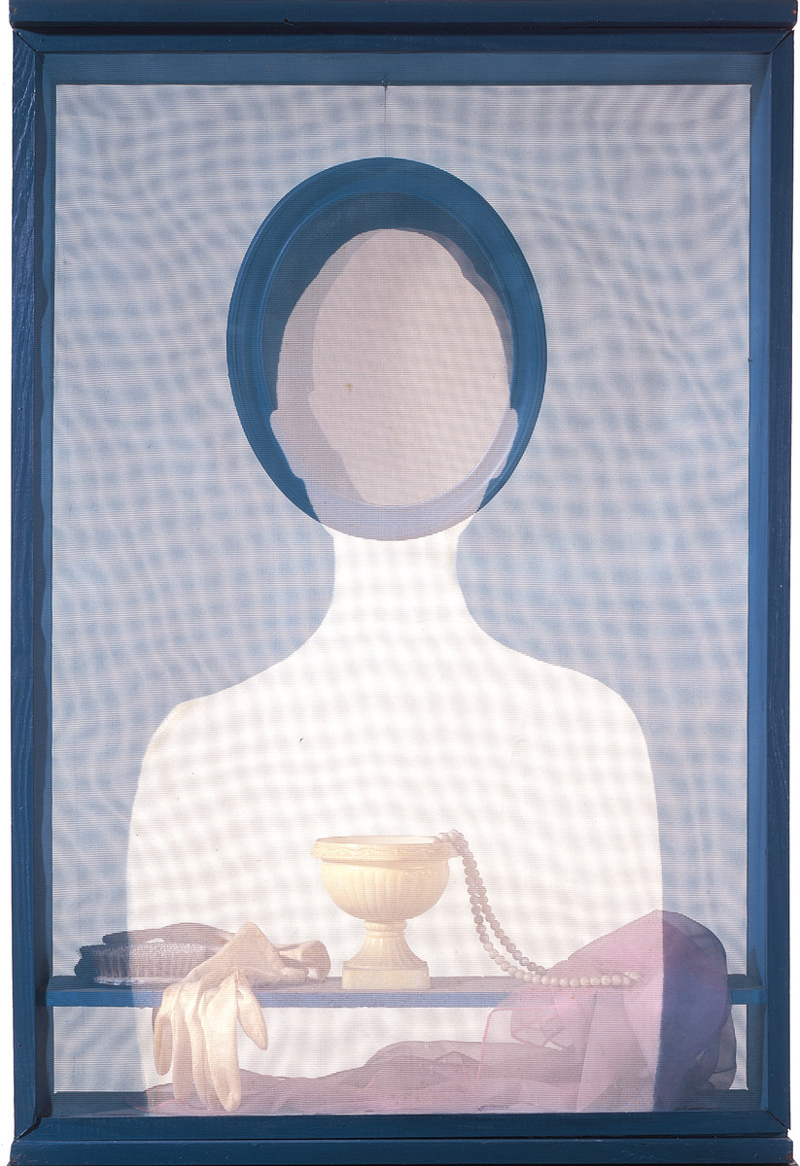

The strange installation by Noronha da Costa, O Azul Eterno do Mediterrâneo [The Eternal Blue of the Mediterranean], keeps us in this imaginary place of threshold and shadows, a limbo in which life and death switch places. Similarly, in the series Tasso, Daniel Blaufuks places partially concealing veils between us and the photographed statues, obscuring our access to their physical presence. The anonymity of these stone figures is common to all the above works, but it is particularly heightened in Toucador [Dressing Table] by Ana Vieira – a delicate evocation of a female archetype, into the centre of which we can project any face that stands before the mirror of the composition.

Archetype becomes allegory in the sculptures of Canto da Maya: Tragédie [Tragedy] and Comédie [Comedy] appear personified in the way in which their figurative complementarity evokes essential principles of theatrical representation and the understanding of existence.

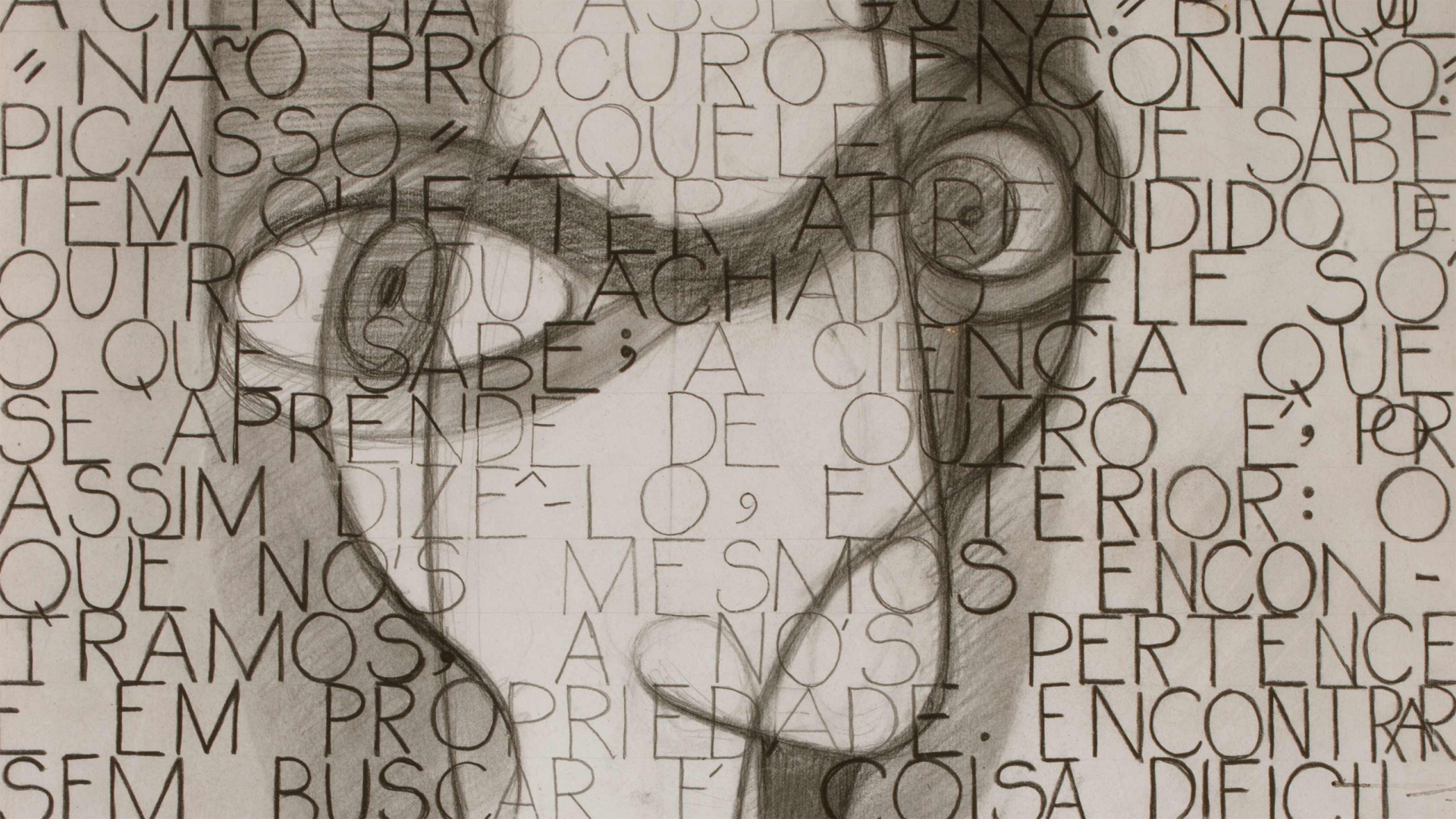

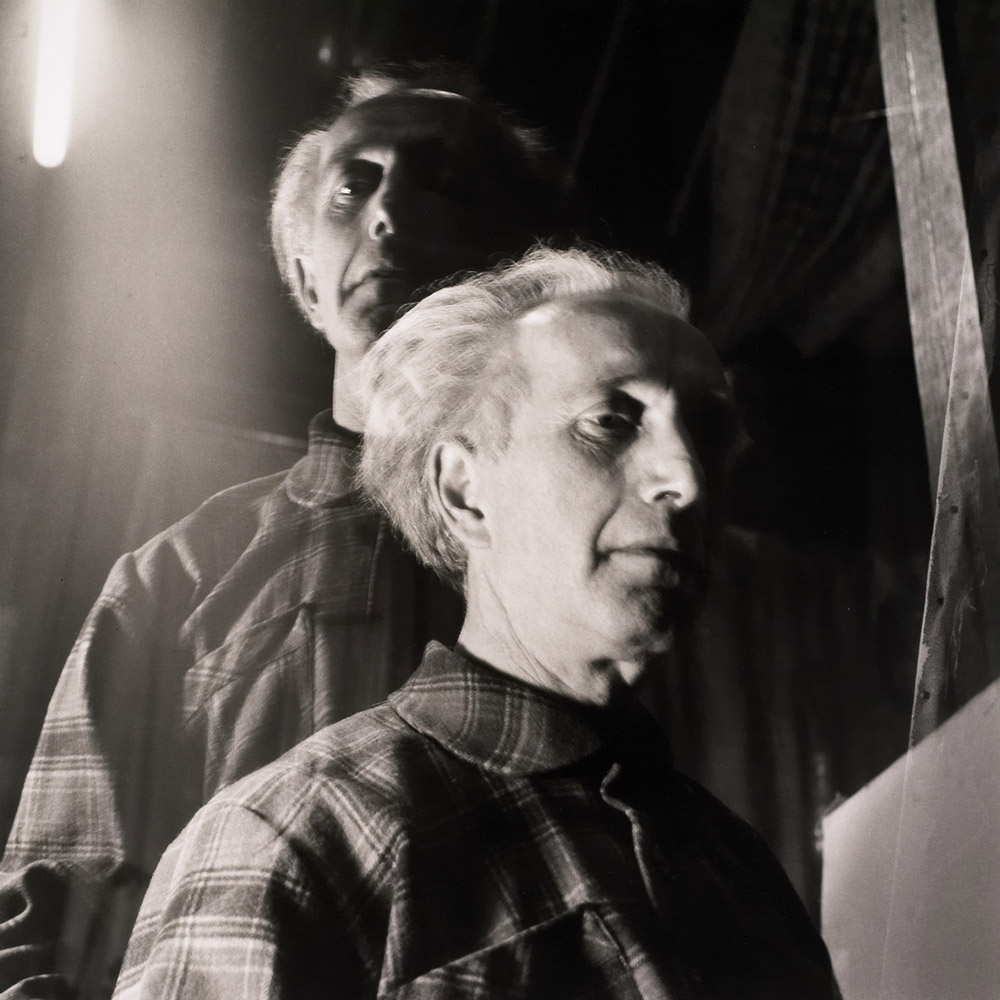

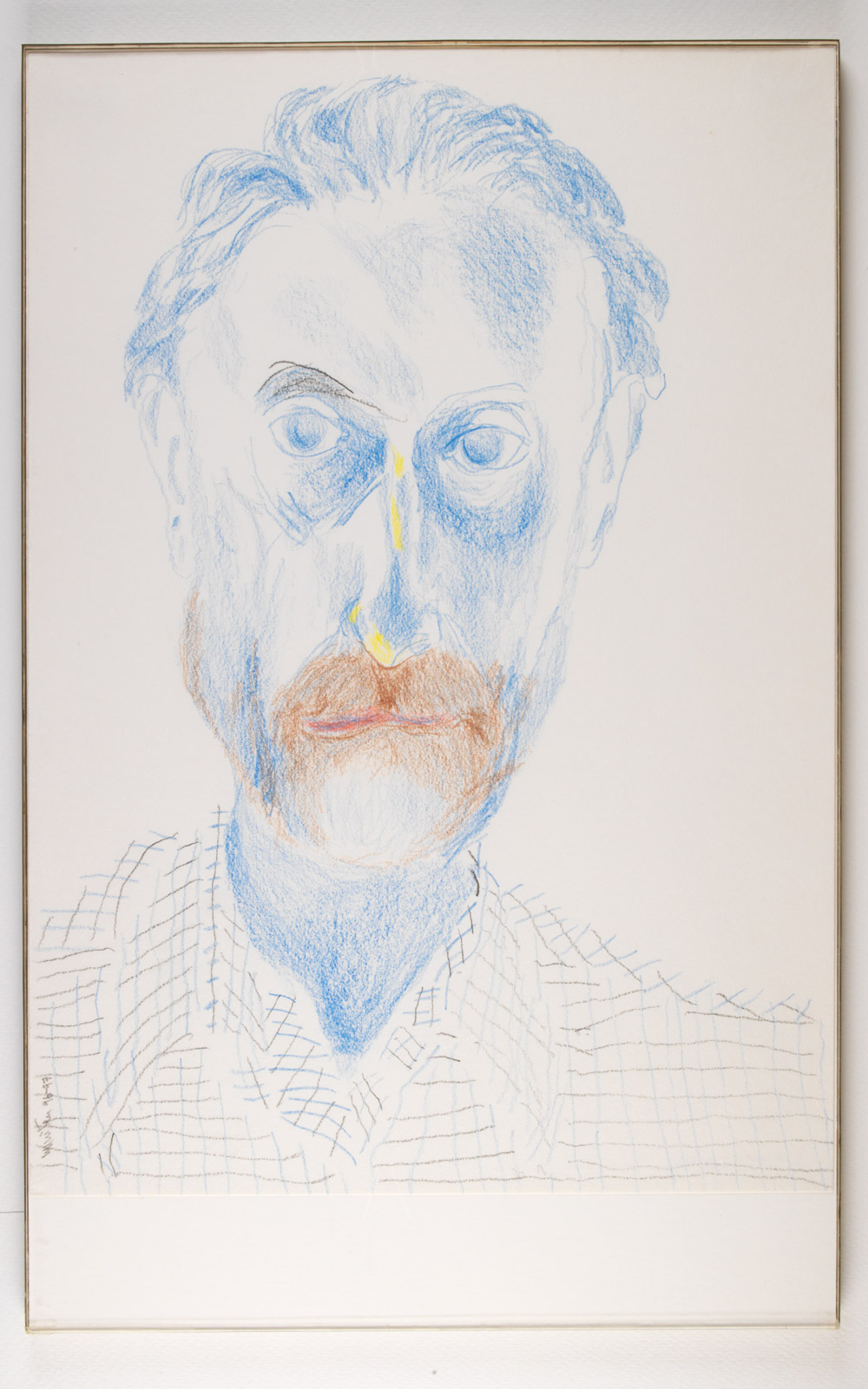

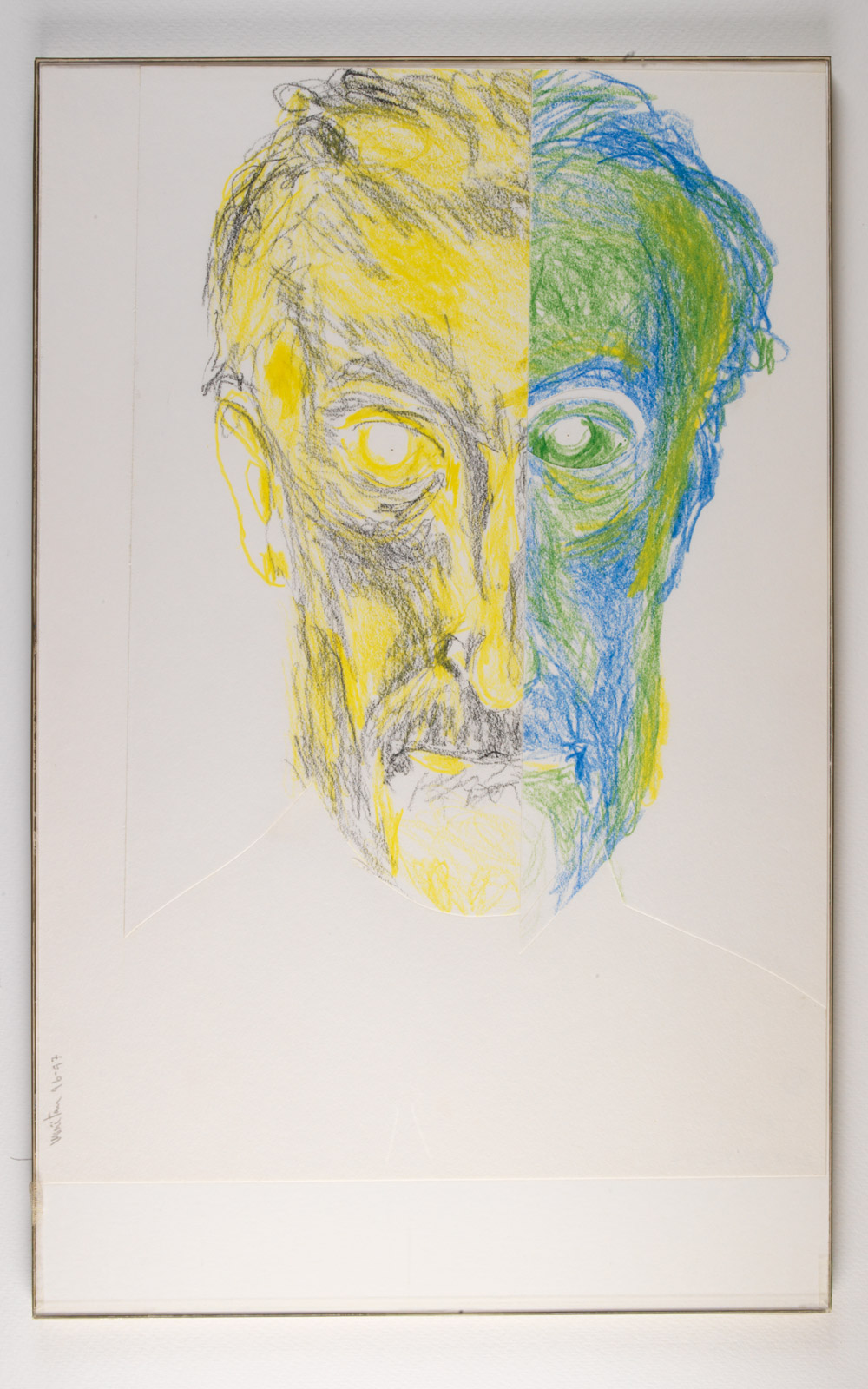

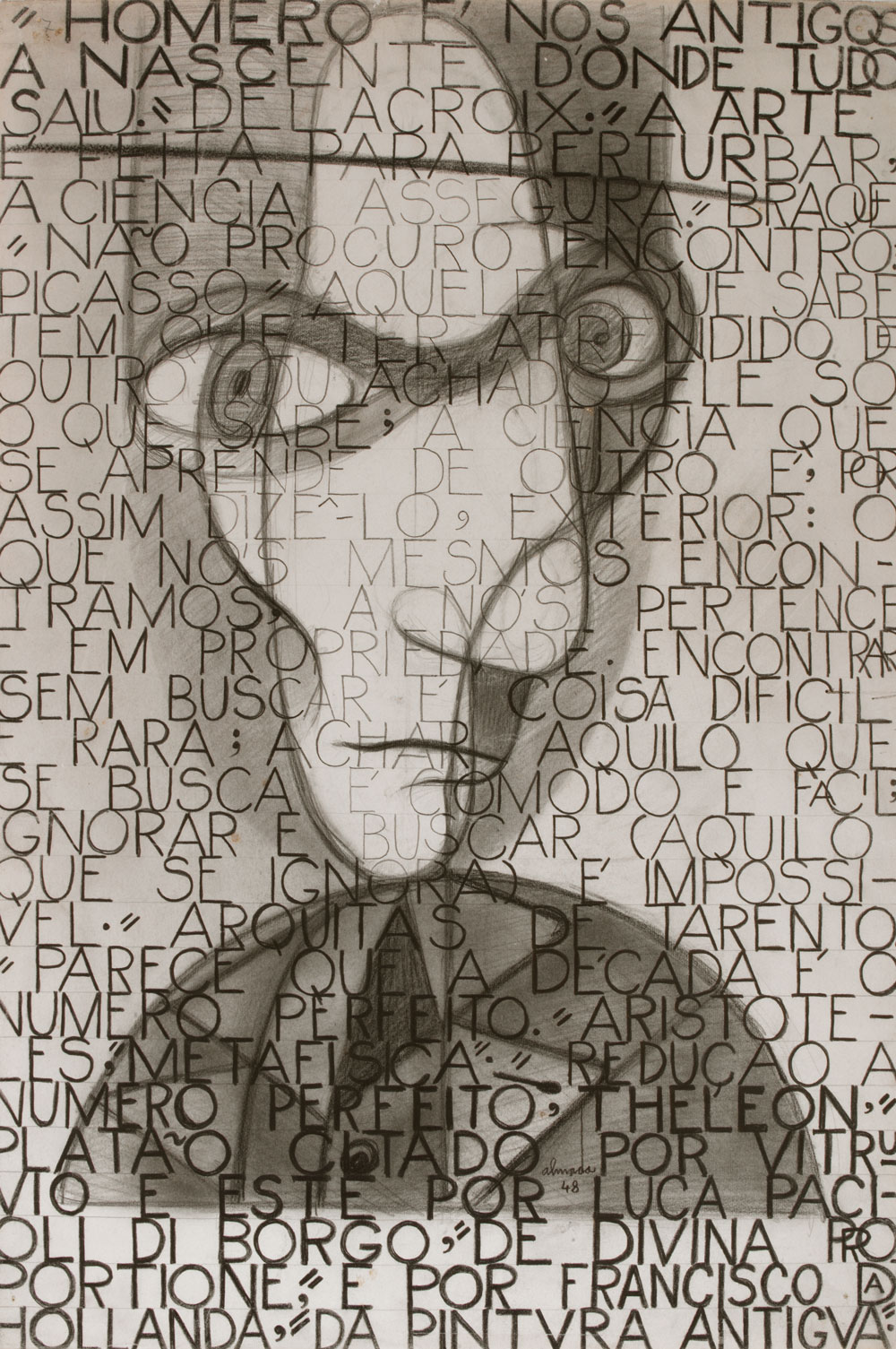

Portrait and self-portrait pay homage to specific people (is self-reference also a form of homage?): with recognisable outlines, as in the case with the self-portraits by Almada Negreiros and Gaëtan; made surreal but clear, as with the artists photographed by Fernando Lemos; or denoted by fantastical metonymy, as in the case of Maria Beatriz’s reference to Almada.

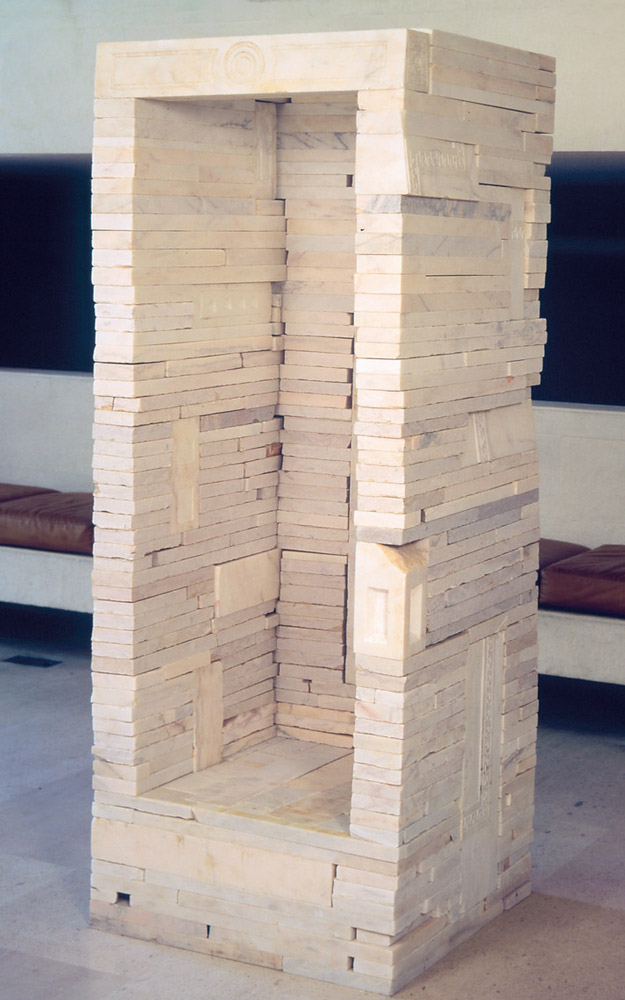

Other types of homage also come to light: to Christmas, in the sculpture by Rui Sanches, which gives critical body or volume to symbolic structures; to Kraftwerk, an electronic music group from the 1970s, through the deconstruction of their musical phrasing, in the video by João Onofre.

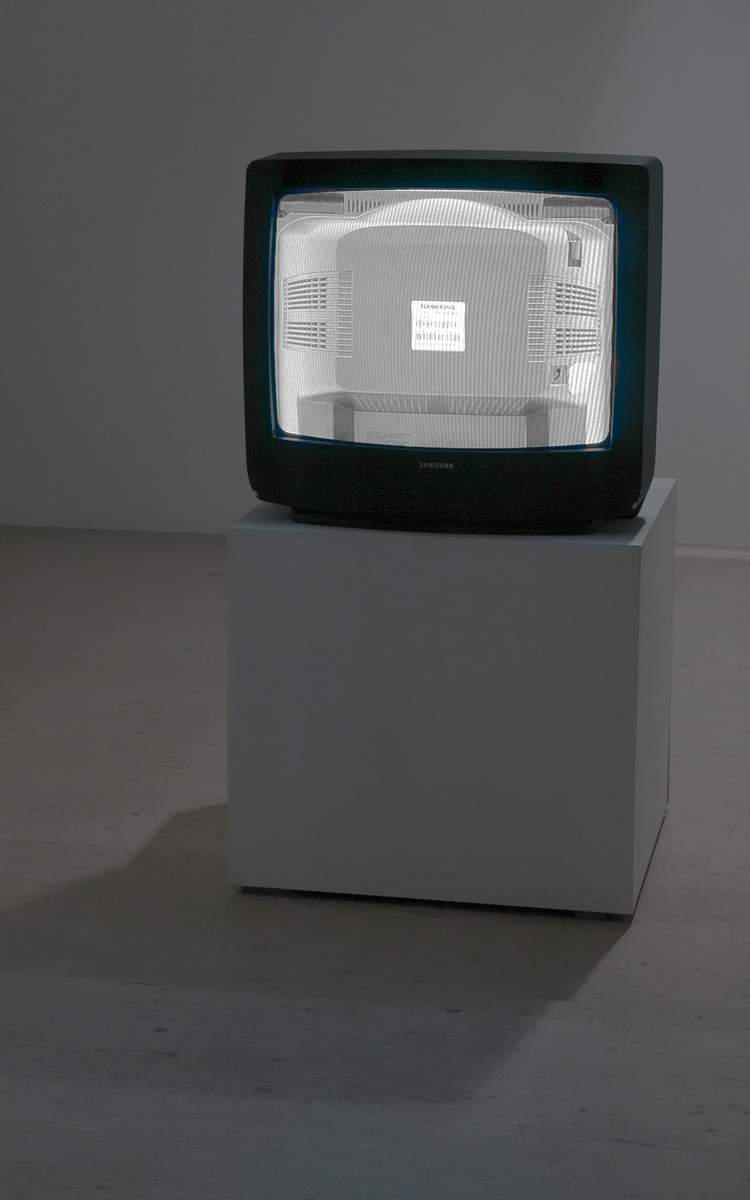

Secular and essential worlds are evoked simultaneously in this recurring movement to fix the spirit of things and of beings. But the dissolution of identities into archetypes, or of archetypes into objects, can be read as a form of oblivion, a voluntary transposition of empirical knowledge to planes in which it either becomes a sublimated evocation of its principles or it extinguishes them. A Casa do Esquecimento [The House of Oblivion], by Cabrita Reis, lies within this territory. Alexandre Estrela’s proposal, TV’s Back, makes radical comment on the closed circuit in which television keeps us absorbed, despite being regarded as an ‘open window on the world.’ And all the other works, if we return to them with this awareness, can be read according to that dual attempt to pay homage and to forget.

Note: Between 4 June and 6 September 2009, an exhibition was held showing works from the FCG’s CAM Collection at the Fundação Eugénio de Almeida, in Évora. It was curated by Leonor Nazaré, with the title Homenagem e Esquecimento (Homage and Oblivion). This text served as a brief introduction.