Social Distancing

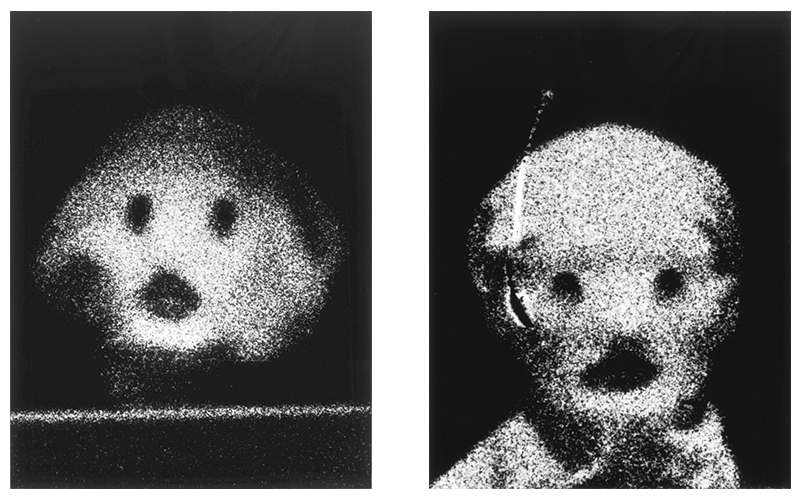

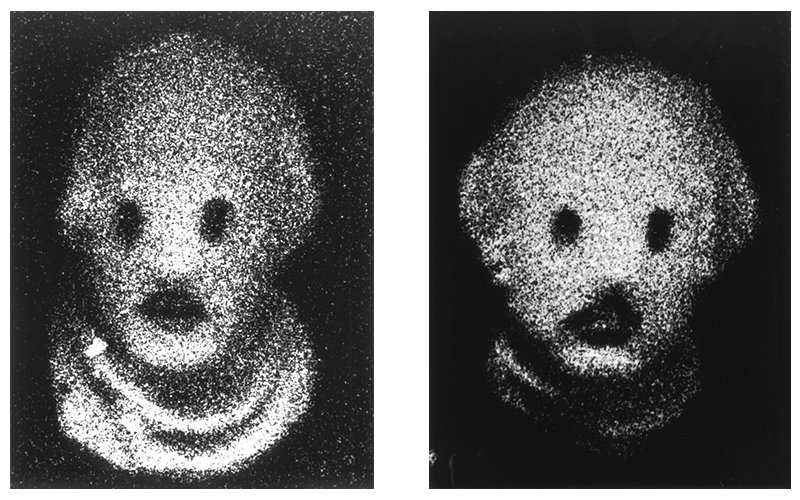

In the early 20th century, in Portuguese prisons, the mandatory wearing of hoods prevented prisoners from identifying or recognising one another. José Luís Neto enlarges the covered faces of 10 prisoners from the negative of a photograph, taken by Benoliel in 1913 in the auditorium of Lisbon’s prison during the official ceremony that marked the end of the mandatory wearing of hoods in prisons, making felt, rather than seen, the extreme physical and psychological incarceration the garment signified: until then, prisoners had been forced to wear it whenever they were in communal spaces.

The total loss of identity and barrier to communication imposed by this situation imbues these ghost-faces with a sense of suffocation, discomfort, fear, indignation and interrogation, their appearance lying somewhere between granite and evanescence, between a crushing weight and the threat of crumbling to nothing.

The eyes, mouth and nose appear as points of closure, all the more pronounced for their hope of being opened. The animal side of the figures is exacerbated, further dehumanising them.

The medium and the negative of the image accentuate the intensity of what they denote.

If solitary confinement in complete anonymity causes strong aversion in the contemporary gaze, and the voluntary exhibition of private life on social networks seems to place it in the opposite extreme to community living, these two extremes nonetheless come into contact in the prison-like condition of constant surveillance.

The work of J. L. Neto and Michel Foucault’s book (Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, 1975) motivated the title of a public conversation I held in the permanent exhibition space of the Modern Collection in 2016 (Portugal in Flagrante, Operation 1) and promoted this meeting between the start and the end of the century, which the organisation of the exhibition as a whole aimed to provide. It presented works, documents and studies that lie at the border between the two typologies, as well as occasional changes to the general chronology, for reasons relating to the nature, concept and referents of the work, as was the case with this piece.

As Semedo Moreira notes, television reports place success and beauty on show, while the guilt of formal suspects or prisoners leads them to hide their faces. But the obligation to do this inside prison denies sociability and individuality, vital for inmates’ recovery.

Portugal’s history of basing its prison systems on imported models, in particular the ‘Philadelphia’ and ‘Pennsylvania’ systems (combining the panopticon with the radial system of constant isolation and permanent surveillance) and the ‘Auburn system’ (which combines isolation with daytime group activities), explains the penal arrangements adopted in Portugal, for example in 1852, in the reform of 1867 and in Lisbon Penitentiary in 1885.

Foucault’s work discusses at length the biopolitical question of normalisation and control, telling the story of prison and punishments for criminality as an instrument for modifying prisoners, in the sense of their social ‘utility’: moulding will, erasing memory, diminishing and changing identity, neutralising the gaze of the other as a mirror.

There is an obvious comparison with the contemporary situation of constant exhibition (online, apparently desired, and imposed by the geo-referencing of all movements, acts of citizenship and consumerism). The debate on this kind of ‘voluntary servitude’ in situations of apparent freedom has brought into consideration what can be recognised in it as the present time. The prisoners’ solitary condition, losing their identity and under permanent surveillance, questions, from afar, the current situation of all internet users and all citizens subject to forms of health or global dictatorship.

Leonor Nazaré

Curator of the CAM

Curators’ Choices

The curators of the CAM reflect on a selection of works, which include creations by national and international artists.

More choices