In relation

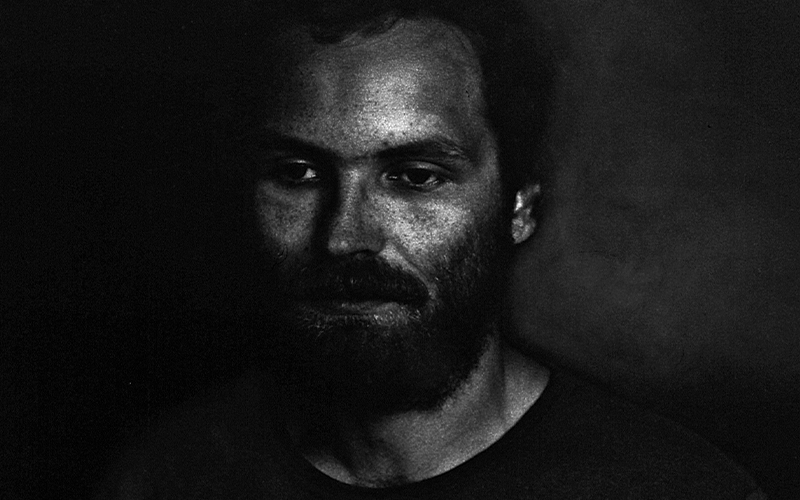

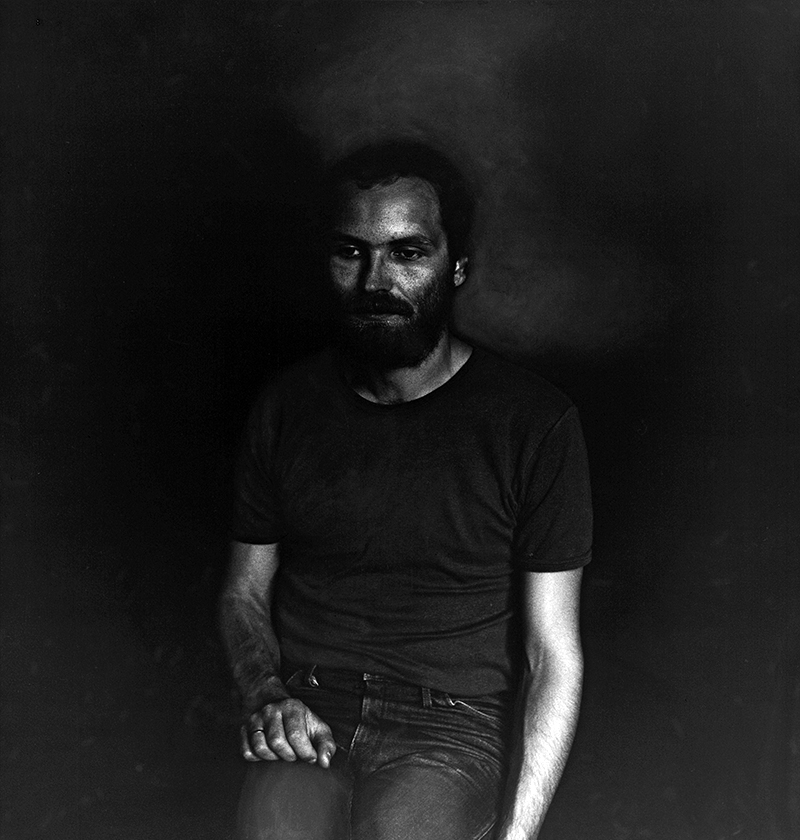

When we visit a museum, we often think about which work we would like to take home with us. If I were to do this exercise with the CAM I would immediately think of this photograph by Craigie Horsfield (Cambridge, 1949), the portrait of a Polish friend of his, a large-scale photograph which looks like a painting.

In choosing this work, I am not intimidated by the fact that it is a portrait of a stranger, about whom I know nothing. I neither offer explanations for the long-standing boundaries between painting and photography, nor respond to a particular taste for a subject-matter or period.

I choose it simply because it is an image that has fascinated me since I first saw it, an image which, for me, exists beyond time and space, on which I have created a lover’s discourse. This capacity for falling in love is quite common among those who like to look at works of art; perhaps one only needs to truly have time to see. However, as is the case with all works of art, this one also points to a much bigger creative universe, which I will now briefly outline.

Leszek Mierwa, ul. Nawojki, Kraków, August 1984 – as if it were an entry in a diary, the title mentions the name of the subject, the place, ul. Nawojki in Krakow, and the date the image was captured – arrived in the collection in 1994. Taken in 1984, during one of Craigie Horsfield’s return visits to the city where he once went to live, leaving London in the 1970s, the image was only printed four years later, in 1988.

Craigie Horsfield’s work has peculiarities that make him an exceptional photographer among the great photographers who, in the 1980s, changed contemporary photography. The unsurpassed quality of the printing is one of these, in an intense studio practice, highlighting the materiality of the image and the particular attention given to the gradations of tones and modulation of light, as is the case of these large black and white portraits which made him famous.

I particularly like the way in which he describes his approach to photography: ‘first part like a conversation, second part like a sketch to a painting, the print, a thought in action’. He combines this very physical and time-consuming process, which often takes place long after the image has been captured, with the production of a single proof, destroying the negative, thus denying one of the main features of photography associated with the potential of its technical reproducibility.

From the 1990s onwards, Craigie began to carry out collaborative projects in specific places, based on lengthy encounters with communities of people, about which he produced books and installations with photography, video and sound recordings. There is an almost epic dimension to his work, an extended sense of time that he calls ‘slow time’, in the desire to capture a ‘deep present’ in the image, for which we possess no other language. Photography emerges as the result of a conversation, something we do every day and which puts us in relation to, with this idea of relation being truly central to his work. As he points out, ‘we are born in relation, we live in relation and we die in relation’.

His very personal way of practising and understanding photography – the complete opposite of taking a portrait, capturing a moment or first impression of something – has made me love his work and hold the desire to always be in relation to his practice and the ideas he defends.

I recommend consulting the catalogue Craigie Horsfield: Relation, a joint edition published by Jeu de Paume, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney on the occasion of the presentation of his exhibition in 2006.

Ana Vasconcelos

Curator of the CAM

Curators’ Choices

The curators of the CAM reflect on a selection of works, which include creations by national and international artists.

More choices