Miguel Branco

S/Título

Castelo Branco, 1963

While mixing paint on a wooden board in 1987, Branco noticed that certain figures emerged spontaneously from the crude matter of pigments. This surface, thus charged with colours in a raw state, only disrupted by lonesome and strange figures lacking either narrative or context, would come to define the idea of material energy on which his oil paintings are still based today. If in his first solo exhibition, Objectos Discretos [Discreet Objects] (1988), Branco mainly showed little human figures sculpted in terracotta, he would in the decade that followed dedicate himself exclusively to oil painting on wood.

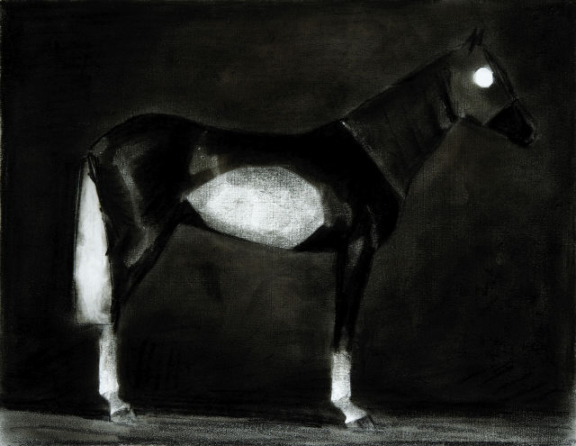

Reacting to David Salle, an artist whose show in Lisbon had impressed him for the gigantic, frontal and garish canvases, Miguel Branco evolved conversely – abandoning the large monochromatic paintings of his student years to cultivate small scales (from 20 to 40 centimetres), nondescript and intangible scenes, and dim colorations. The successive exhibitions and thematic series of oil paintings in the early 90s helped him to consolidate a personal pictorial idiom and a conception of the picture as a strictly visual object, leaving all works untitled so as not to burden them with literary tics. Such a purism distanced Branco from his neo-expressionist generation, seeking a refuge against those excesses in Chardin, whose abstract and monochromatic backgrounds, with their ability to convey a powerful effect of material presence, he studied. Around the same time, in New York, he became fascinated with the dioramas in the Museum of Natural History, a sort of showcase enacted to create the illusion of landscapes, animals or historical events. Moved by this combination of “science, theatre, and magic”, he set out to create his enigmatic series of lonesome animals, within a similar state of limbo, “between reality and hallucination”, where his painting embarks on a constant self-discovery. And so the birds, the monkeys, the ostriches and the dogs, that had been caricatural in 1989, gained a stronger naturalistic presence as the unique motif of his oil paintings.

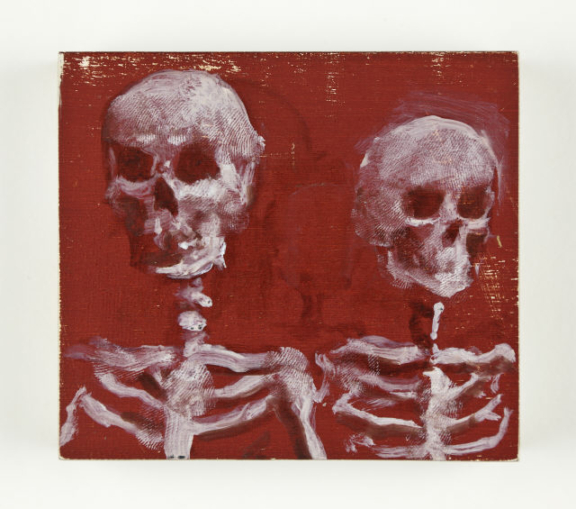

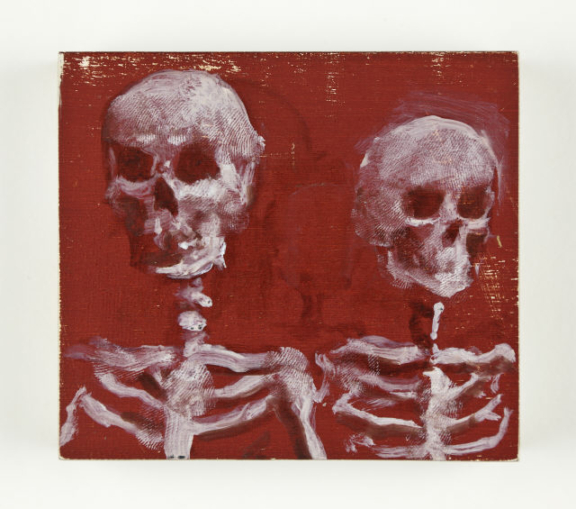

Though he prefers image references that historically depend upon an elaborate symbolic language, Miguel Branco refuses to convey their attached iconographical meanings. His animals never assume human postures, like in ancient bestiaries, nor do his skulls ever come near of the tradition of vanities. In fact, Branco intensifies this detachment of interpretation in his portraits of faces hidden behind masks, or through such inexpressive figures that preclude any psychological recognition by the onlooker. It was this estrangement that led him to explore visual solutions such as scenography, the stage, abstract surfaces and artificial arrangements, in a particular phase strongly influenced by the operatic ideal of Italian eighteenth-century painting.

An artistic crisis forces Branco to change Lisbon for London in 1996, and to quit painting for six months. It was a time to experiment drawing and sculpture in Fimo, testing new techniques and new materials to help clarify his pictorial work, which he soon resumed, with the benefit of his deepened knowledge of the work of Stubbs, Bacon and especially Luc Tuymans. The pictures of this phase of anxiety are dark and monochromatic, but paint seems to be looser and freer, highlighting brushstrokes and figurative forms such as clouds, beds or dogs. When he returns to Lisbon, in 1998, the scale and melancholy of his oil paintings diminished drastically, in luminous landscapes made only of clouds, mountains or still water.

He enters the following decade painting heads, using opaque shapes, with cavities instead of eyes. Thus he not only avoids identification, but also soon subverts it, using grotesque and paranormal elements from sci-fi, fantasy or S&M, in bizarre and monstrous figures that evoke as much the film Freaks (1932) as Diane Airbus’ photos. This profane imagery, both extravagant and artificial, entwines however with historical images from the following series, in which Branco transfers theatrical figures from the fêtes galantes painted by Watteau or Fragonard, isolating them against an abstract background in Rococo pastel colour. The scope of his references extends quickly, judiciously blending citations from the Planet of the Apes (1968) to erudite painters such as Brueghel or Bosch.

To rediscover the painting he had abandoned for two years, he went back to sculpture in 2005, using the childlike and expressive clay material of Fimo, casting animals from natural history, like dodos and headless horses, and objects such as bean bags or black eggs spurting blood, in semi-surrealistic semi-abstractions of a vast formal diversity. Recently, however, he started sculpting in bronze and aluminium, and the scale of his works increased abruptly – though always within the intermediate, historically dislocated reality between man and animal that is he able to show and hide at the same time, in the perpetual prospect that something is about to be revealed.

AR

January 2011

S/Título

S/Título

S/Título (Pequena figura sobre fundo verde) [Untitled (small figure on green background)]

S/Título (a partir de George Stubbs)

S/Título [Untitled]

S/Título (a partir de George Stubbs)

S/Título [Untitled]

S/Título (Pequena figura de esquiador com fundo amarelo) [Untitled (Small figure of skier on yellow background)]