Manuel Botelho

116.rç-cmb (from the series 'confidencial/desclassificado: ração de combate')

Lisbon, Portugal, 1950

The closing of the 60s would be crucial for Botelho, starting his fight against the political atrocities of his time, at the same he also began militantly his formal artistic education. In 1968 he studied drawing with Sá Nogueira at the National Society of Fine Arts in Lisbon, made his first appearance in group exhibitions and started studying Architecture at the Fine Arts School in Lisbon. In the following year, he began working at the architecture studio of his father, Rafael Botelho, and travelled to several European capitals, in whose museums he could increase his visual culture of painting, in which his grandfather, Carlos Botelho, was still a national reference.

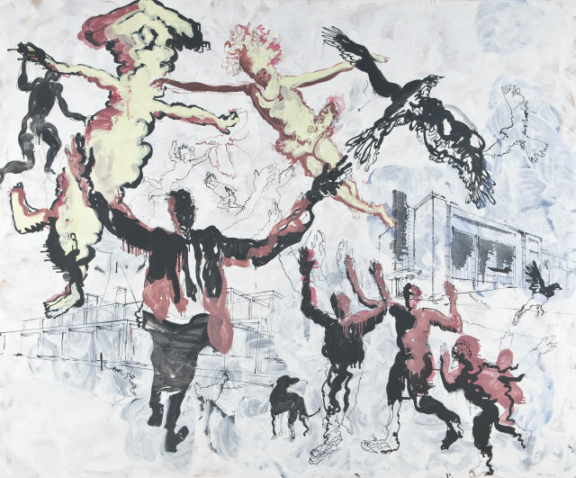

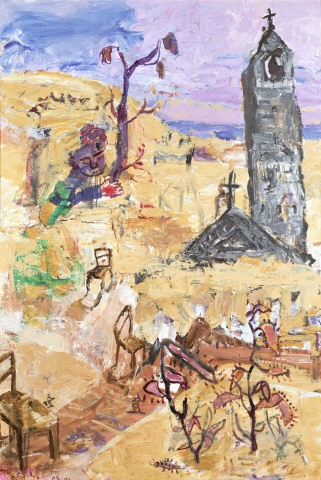

On his first solo exhibition (1977) Botelho featured drawings, but it was as an architect that he occupied most of his time until he decided to leave to London in 1983, as a Gulbenkian scholar in the Byam Shaw School of Art, enrolling in Wynn Jones’ studio of Image Painting. Right after that, he undertook postgraduate studies at the Slade School of Art, where he met Ken Kiff and was tutored by his compatriot Paula Rego and Jeffrey Camp – and all of these he would later bring together in an exhibition in London entitled Friends of Botelho (1992). If figuration and narration seemed to be the main binomial of his first artistic endeavours, much due to Sá Nogueira’s Pop influence, Botelho’s closeness with these London artists and the narrative tradition of British art led his paintings to foster the strident figurative style of New Image Painting – also reflecting his particular admiration for Philip Guston’s work, to which he later devoted his Ph.D. thesis. Brushing with dark and thick paints, through an unfettered neo-expressionist ferocity, Botelho would fill up his canvases with a cartoon-like figuration, representing either personal accounts of episodes of anxiety and despair, or hypercritical images of Portugal’s social and cultural misery in the time of Salazar, depicting the country as a pious and tacky province.

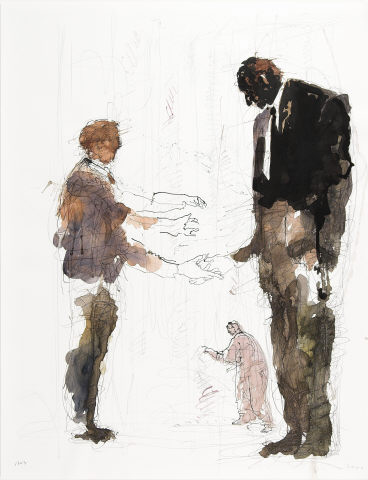

Botelho soon embraced the artistic compromise of showing his personal terrors, whilst keeping with an ethical sense of political intervention. But on his return to Portugal (1987), the violence of such concerns was temporarily numbed out by a more formalist research on the legacy of Cubism. The trace gradually imposes itself on the former chaos of colours, establishing an order of geometrical forms, strong textures and contrasts, a wider chromatic variety and fragmented bodies with an overt erotic intention. The following series, however, resumed his social and political vocation, dwelling in autobiographical episodes that were transformed into archetypes of bigger situations. Thus, he used his own experience as high school teacher in the suburbs (1995-1998), in a series of images that triggered the collection of profane subjects that still thrive in his work: scenes of violence, sexual and political scandals, with child soldiers, saints, ministers or addicts that can either emulate a pose found in television or newspapers, or else models taken from Poussin or Botticelli – thus confronting, and somehow atoning, that which is personal with the universal, modernity with tradition, high with low art. This tension of opposites soon invaded the surface of his drawings and paintings, either by self-representations as Christ, or in ambitious neo-Mannerist compositions of religious and media events, combining contradictory forms, spaces and artistic languages with a tremendous expressiveness.

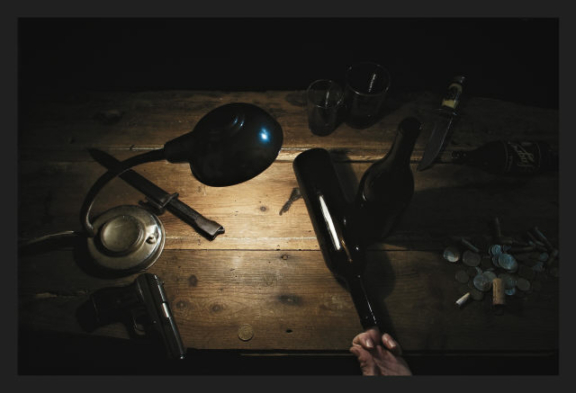

The weight and density which largely defined his images’ settings in the 1980s, would be replaced by solutions of transparency and lightness, as the line triumphed over colour, in such a way that in his images from the first decade of the twenty-first century, his characteristic imagery of tormented bodies, adornments such as guns and microphones, or the usual background of Modernist buildings, almost seem to be floating in space. However, the formal diversity that Botelho inaugurated in the 90s also brought about a certain need to overturn the ways he had been trailing in drawing and painting, by experimenting, for instance, installation artworks, when he put a group of programmed traffic lights near the Calçada de Carriche in Lisbon (1993), or conceived a panel of azulejos (ceramic tilework) for Beja (1998); and, as that underlying crisis in painting and drawing soon became evident, Botelho decided to abandon both for a two years period, when he used instead photography (2006-2008) to tackle his experience and view of the Portuguese Colonial War, a recurrent subject in his work that he nevertheless always manages to recycle in an unexpected manner given his artistic versatility.

Afonso Ramos

January 2011

116.rç-cmb (from the series 'confidencial/desclassificado: ração de combate')

119.flg (from the series 'confidencial/desclassificado: flagelação')

112.rç-cmb (from the series 'confidencial/desclassificado: ração de combate')

157.md-grr (from the series 'confidencial/desclassificado: madrinha de guerra')

134.md-grr (from the series 'confidencial/desclassificado: madrinha de guerra')

141.md-grr (from the series 'confidencial/desclassificado: madrinha de guerra')

137.md-grr (from the series 'confidencial/desclassificado: madrinha de guerra')

144.est-mr (from the series 'confidencial/desclassificado: estado-maior')

133.md-grr (from the series 'confidencial/desclassificado: madrinha de guerra')

155. est-mr (from the series 'confidencial/desclassificado: estado-maior')

147.mr-lt (from the series 'confidencial/desclassificado: marcha lenta')

164. mss-cp (from the series 'confidencial/desclassificado: missa campal')

167. mss-cp (from the series 'confidencial/desclassificado: missa campal')

Matchbox: Portugal is not a Small Country

S/ Título

101.rç-cmb (da série Confidencial/Desclassificado: ração de combate) [101.rç-cmb (from the series Confidential / Declassified: combat food)]

Rendição

S/ Título

100.rç-cmb (da série confidencial/desclassificado: ração de combate) [100.rç-cmb (from the series Confidential / Declassified: combat food)]

Visita

Sufoco – White Dust [Suffocation – White Dust]

Rendição – Hostage Crisis

Pietà

Areia e Sal – Igrejas Silenciosas

Visitação

A Instituição