José Dominguez Alvarez

sem título

Porto, Portugal, 1906 – Porto, Portugal, 1942

After completing his basic education, José Dominguez Alvarez went to Pontevedra to undertake business studies, but, disillusioned with the job prospects that this training would give him, he returned to Oporto and, against the will of his parents, enrolled at the School of Fine Arts.

He immediately aligned himself with breakaway positions and, in 1929, together with a group of lower-year students, he produced the manifesto of the +Além group. Inspired by another manifesto, ¡Máis alá!, which had been published some years earlier in Galicia by the poet Manuel Antonio and the painter Álvaro Cebreiro, the +Além manifesto criticised traditional Portuguese landscape art and advocated avant-garde modernity.

His involvement in the +Além group allowed Dominguez Alvarez to gain recognition and to participate in his first group exhibition, which took place in November of the same year at the Salão Silva Porto. The exhibition represented a genuine show of support for Dominguez Alvarez. Above all, he was recognised by his fellow group members, who considered his works to be indisputably superior to the other pieces on display. A few months later, he exhibited his work again in the same place in the company of Artur Justino, a fellow member of +Além. This exhibition was enlivened by a lecture on modern art by the poet Adolfo Casais Monteiro, who would go on to become one of the main supporters of Alvarez work. The exhibition also attracted the sympathy of other intellectuals, such as Alberto de Serpa, Miguel Torga or José Régio, who would always praise his work.

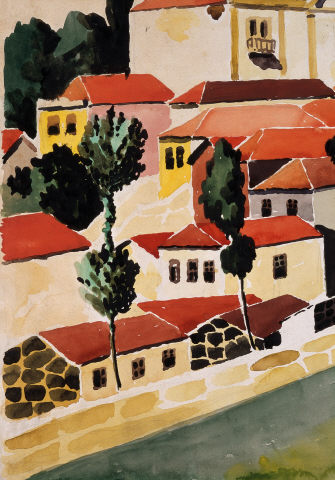

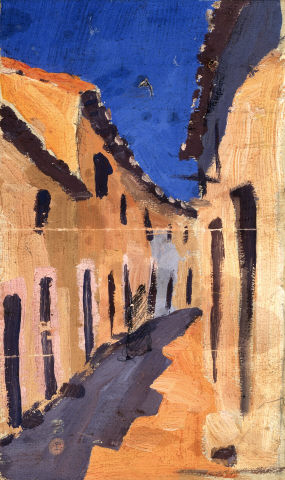

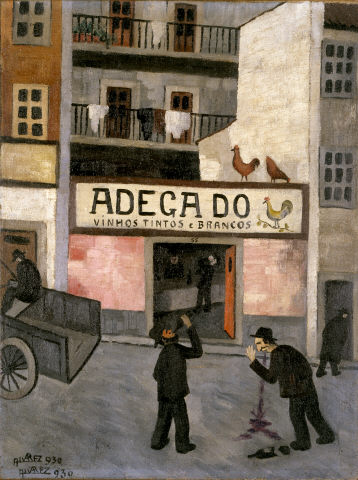

The paintings shown at these early exhibitions form part of what is known as his first period of painting (the red period, 1926-1929), characterised by the use of bright, intense and unelaborated colours. With regard to subject matter, he showed a preference for urban landscapes, working-class neighbourhoods, and the detours and alleys of Oporto, as seen in Casario com roupa à secar [Houses with drying clothes], Sé do Porto [Oporto Cathedral], and Telhados [Roofs]. The series of “fabrics”, which calls to mind the paintings of Milanese suburbs by Mario Sironi (1885-1961), also dates from this period.

What could be seen as his period of consolidation (1929-1936), which was also his most personal, complex and interesting period, began in 1929. During this period, he continued to explore his personal imagery, and some of his most significant works, including Homens tortos [Twisted men], Casario com homens tortos [Houses with twisted men], and Casario e figuras de um sonho [Houses and figures from a dream], are the fruit of this period: cityscapes with expressionist connotations populated by wandering drunks and hats, stooped men always dressed in black – figures of a tremendously modern and very suggestive ingenuity.

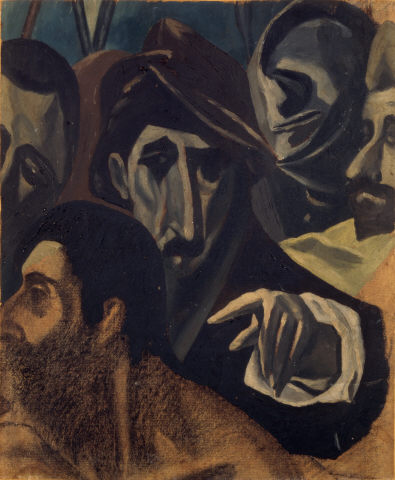

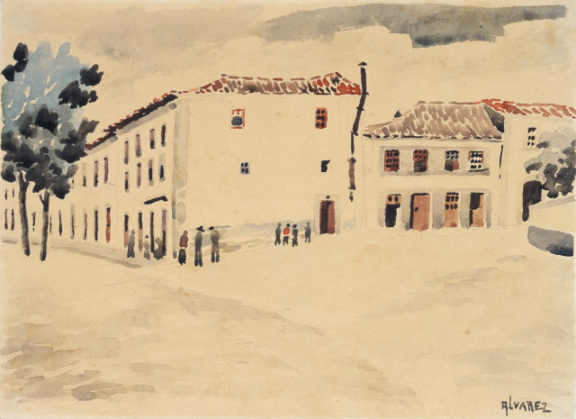

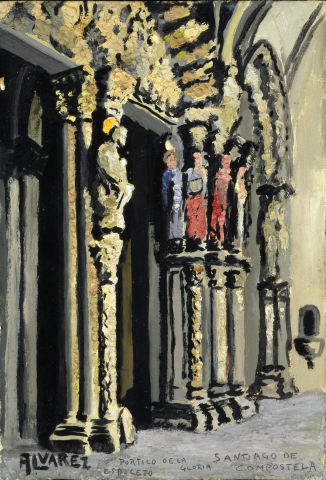

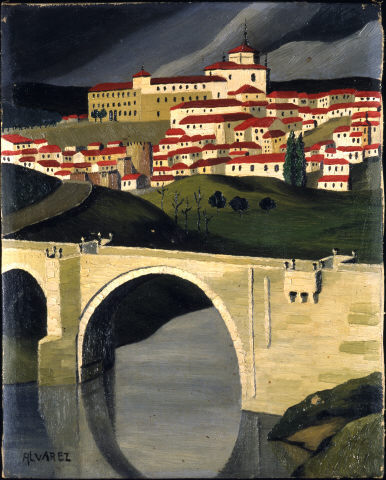

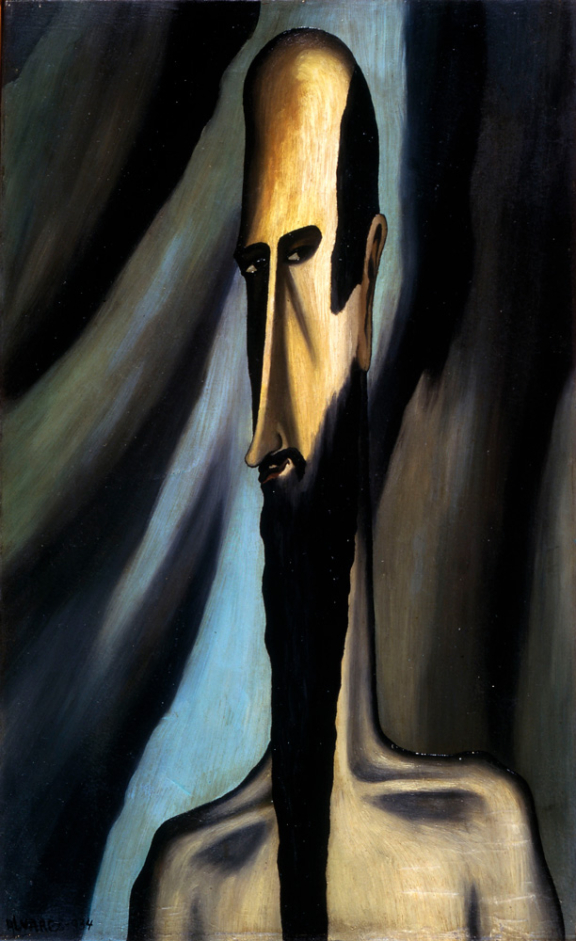

But it was also during this period that Dominguez Alvarez undertook a long journey around Spain which profoundly influenced his work. The journey allowed him to come into direct contact with the Castilian landscape, to frequent Spanish museums, to study El Greco’s work close up, and, above all, to gain first-hand knowledge of the paintings of José Gutiérrez Solana (1886-1945), Ignacio Zuloaga (1870-1945), Darío de Regoyos y Valdés (1857-1913) and Aureliano de Beruete y Moret (1845-1912), all of whom made a great impression on him and led him to abandon the style of painting that he had done so far in favour of his landscapes such as Segóvia ou Paisagem com castelo [Landscape with castle]. It was also under this influence that he painted O Bispo [The Bishop], Louco [Crazy], Homen Compostelano [Man from Compostela] and Don Quixote, strange figures lying somewhere between proximity and unreality, generally portrayed in dark, opaque, unreal colours, which were highly original within the Portuguese visual arts.

During these years, Dominguez Alvarez also showed signs of possessing a clear iberist inclination and an enormous interest in becoming an artist who served as a bridge between Spain and Portugal, or, more specifically, between Galicia and the north of Portugal. In fact, he tried to organise a great exhibition of Galician art in Oporto, for which he made contact with artists such as Alfonso Rodríguez Castelao (1886-1950), Francisco Llorens Díaz (1874-1948), Carlos Maside García (1897-1958), Arturo Souto Feijoo (1902-1964) and Laxeiro (José Otero Abeledo, 1908-1996). However, his limited influence in artistic circles on both sides of the border, the scant interest that they showed in the project, together with the difficult political circumstances of the day, caused this attempt to end in failure.

This disappointment, together with the spreading of the tuberculosis from which he had suffered since he was very young and his disillusionment with the political direction in which the peninsula was heading (in 1936 he renounced his Spanish nationality), explain why Dominguez Alvarez in some way ended up faltering in his artistic, and even personal, commitment, ultimately confirming the views of those who had, since the beginning, advised him against his modernist whims. It was at this point that his third and final period began (1937-1942). It was a period of recognition and disappointment during which the painter abandoned his particular vision of reality, the sombre portraits that contain hints of Zuloaga, the palette of Solana, and the skies of El Greco, in order to move increasingly closer to the path of Joaquim Lopes (1886-1956) or Marques de Oliveira (1853-1927). From that point onwards, he was to paint many landscapes of the surroundings of Oporto, almost all on a small scale and with great chromatic harmony; exercises of great virtuosity which were very pleasant and very melancholic, but which lacked the modernity, the air of unreality and daring, which had characterised his previous works.

AT

sem título

Estudo (Cópia de Greco)

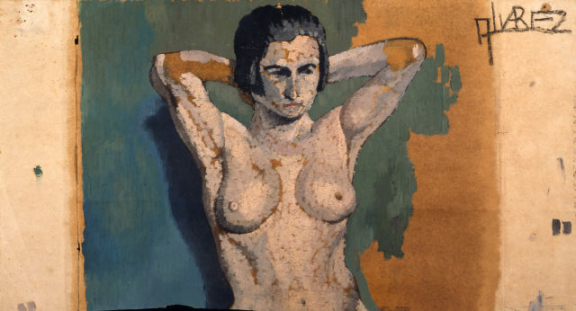

s/título (Nu – pormenor)

s/título

Paisagem de Contumil

sem título (Rua com casas)

sem título

sem título (Figuras)

sem título

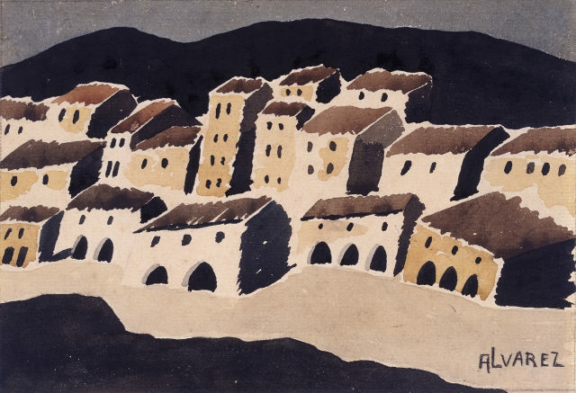

Casario (Galiza)

Flores (Estudo)

sem título

Segóvia

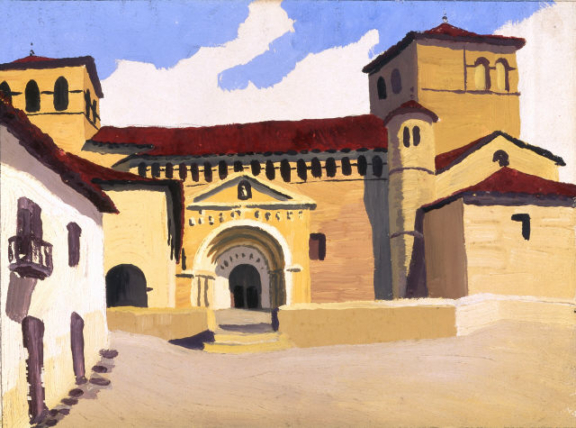

Catedral

Paisagem de montanha

sem título

sem título (Rua ao Sol) [untitled (Sunlit Street)]

Paisagem

Paisagem

sem título

Casario e figuras de um sonho [Houses with figures from a dream]

Louco

sem título (Aspecto de rua com figuras) [untitled (View of a street with figures)]

Pórtico da Catedral de Santiago de Compostela

sem título

Paisagem

sem título

Catedral de Segóvia

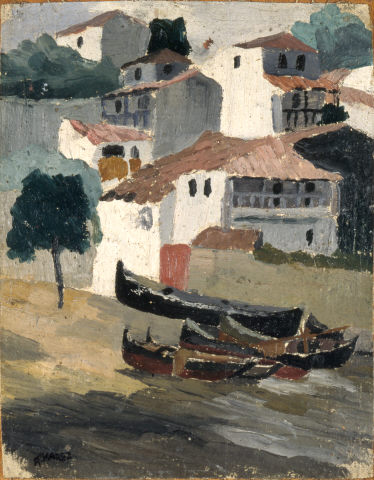

Paisagem – Casario e barcos

sem título

Paisagem

Auto-retrato

Paisagem de Frias

Paisagem com casas

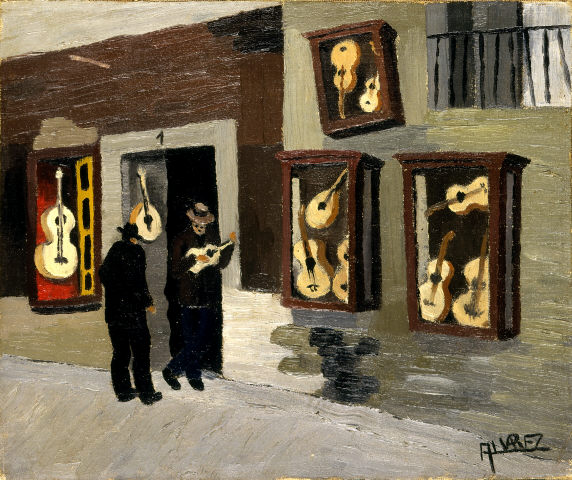

Casa das Violas

D. Quixote

Paisagem com castelo

Adega do Galo

Paisagem com ponte