Adriano de Sousa Lopes

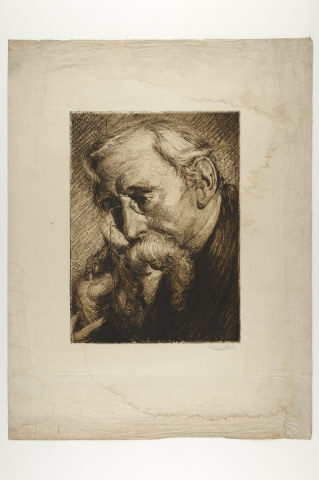

Auto-Retrato

1879 – 1944

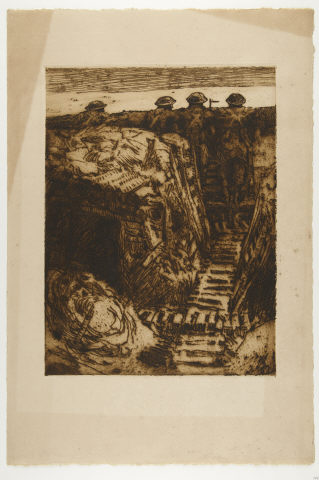

In 1903 he moved to Paris to study history painting as a beneficiary of the Valmor legacy. He attended the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts and the Académie Julian where other artists such as Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard had also studied, graduating with Fernand Cormon, an academic painter celebrated for his history painting. Also in Paris, Sousa Lopes exhibited in several editions of the Salon d’Automme (in 1904, 1905, 1906 and then once again in 1908, 1909 and 1912). In 1915, he organized the Fine Art Section of the Portuguese Pavilion in the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition, held in S. Francisco, California (U.S.A.). In 1917 he had his first individual exhibition at the National Society of the Fine Arts (SNBA), in Lisbon. That same year he went to the front of the First World War as the army’s artist, with the degree of captain.

After the armistice, Sousa Lopes traveled across Europe and North Africa, with intermittent seasons in France and Portugal, until 1927, when he once again exhibited. That same year, he became director of the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Lisbon, on indication of its former director Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro . Being an academic artist and member of the National Academy of Fine Art (1932), Sousa Lopes was officially commissioned to produce several works throughout the 1930’s, such as the decorative paintings for the ceremonial hall of the National Assembly or for Lisbon’s Military Museum. Moreover, as part of the organizing committee he collaborated, alongside Reynaldo dos Santos (1880-1970) and João Rodrigues da Silva Couto (1892-1968), in historical and commemorative exhibition projects, such as the Exposition de l’Art Portugais (Musée du Jeu de Paume, Paris, 1913) or Os Primitivos Portugueses (1450-1550) [Portuguese Primitive Painters] in Lisbon (1940).

As can be verified in the collection of works belonging to the CAM, Sousa Lopes was both a prolific and technically versatile artist, praised for his skill in the use of color, who embraced a vast array of themes with ample stylistic variation. Oil paintings, both on canvas and wood, watercolors and drawings (aquatints, etchings) dominate the artist’s catalogue. Through this variety of techniques Sousa Lopes produced portraits (No salão, Retrato da Senhora F.C. em vestido de noite; Mlle H.L. dans l’atelier de Souza), interior scenes (Num salão, senhora e homem encostado numa chaminé), images of social and mundane gatherings (expressionistic study of a quasi caricatural nature in Untitled), still lifes (Natureza-morta, 1910) heritage themes (Évora d’Alcobaça) and history paintings such as the Episódios do Cerco de Lisboa [Episodes from the Siege of Lisbon], one of which received an Honorary Mention in the Salon d’Automme of 1906.

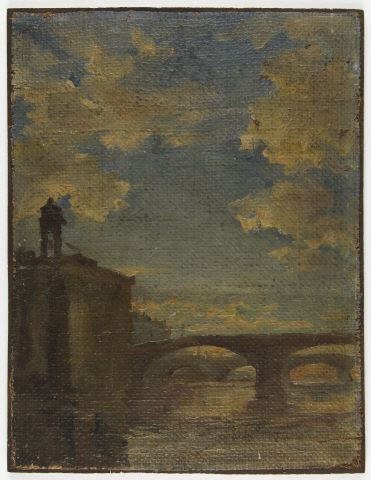

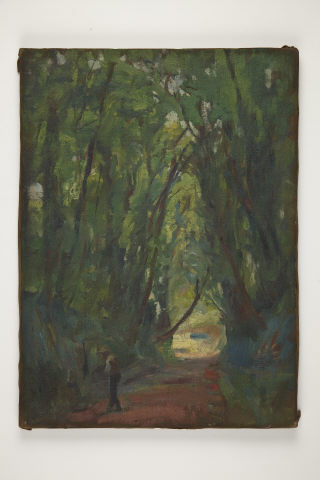

However, it is in his landscape paintings that Sousa Lopes best exemplifies his personal vocation: numerous versions of marine landscapes and skies (Mar e céu, undated and 1923), views of the seafront or of Portuguese cities and villages (Paisagem portuguesa) and of the countries he visited (France, Belgium, Italy, Morocco and Spain) or an unusual view of a pine forest (Caminho na Floresta) reveal a fascination with weather – at times endeavoring in an impressionistic decomposition of the scenery and its elements (sky, clouds, water) through lighting and shading effects – and time, paying particular attention to the time of day and the transfiguration of the perception of space induced by the variation of luminosity and coloration depicted in the scenes.

The concern with time and weather is evident through Sousa Lopes’ choice of titles: Noite no Canal [Night at the Channel], Os Telhados de Montmartre à noite [Montmartre Rooftops at night] or Pôr-do-sol [Sunset] are some of the works in which one can best perceive the effect of an impressionistic brushstroke, demonstrating the artist’s interest in the passing of time and in the changes in form, color and light.

Another interesting aspect is the intimate scale of a great part of his pictorial work, the interest in the direct representation of nature, the small dimensions of his pictures – at times, brief and expressive jottings of color and movement. This strongly contrasts with the monumentality and historical fixation of works produced through private or institutional commissions, such as the fresco panels conceived for the Palace of Sao Bento in Lisbon, which were never completed.

Maintaining a certain distance to the social realities of his time, Sousa Lopes appears as a somewhat paradoxical personality, even more so when taking into account his appreciation of the interrogation of time within the painted image. His understanding of painting as a form of refuge, entertainment, or historical narration (epic or folklore) places him in a direction that counters the concerns of the international movement of Modernism. In this, he contributed, in twentieth-century Portugal, to prolong a conception of painting founded on naturalistic precepts and a mnemonic, decorative or illustrative functionality, revised through the Impressionism he would later defend as the adequate style for the “Portuguese sensibility” (Conference in the Lisbon Rotary Club in 1929).

His images of work (in particular of traditional fishing, which fascinated him), of popular types (Nazarena, or Italiana), of traditional celebrations such as religious processions, are, especially in his mature work from the late 1920’s onward, mostly peaceful illustrations of a tranquilly drawn reality understood as a natural and immutable condition, avoiding any expressionistic distortion. Sousa Lopes’ particular concern with popular craft-work and customs appears always imbued with a certain disdain toward the human, also present in his conventional portraits of models and human figures (Mlle. H. L. em fato de passeio; Num salão, rapaz com um arco; Num salão, Mlle H.L. e sua irmã…).

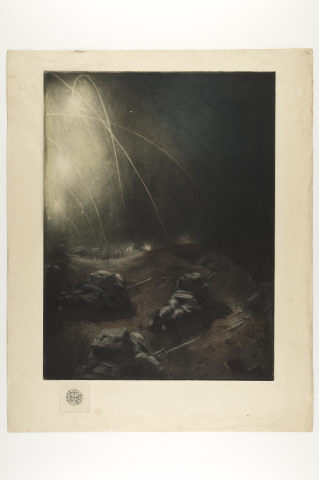

Through the trips and (numerous) sojourns in Paris, Venice, Rome, or finally through the desolation and suffering of the First World War and its fracturing of civilization, which he viewed from the front as the official in charge of the iconographic representation of the Portuguese Expeditionary Corpus, between 1917 and 1918 (the CAM possesses some fine examples in etchings), Sousa Lopes had a direct contact with the geography of modernity. This seems to have provoked a sort of immunity to the spirit and ideals of Modernism which Sousa Lopes, defined by Afonso Lopes Vieira as a “contemporaneous primitive”, fundamentally declined throughout his life.

Ana Filipa Candeias

December 2010

Auto-Retrato

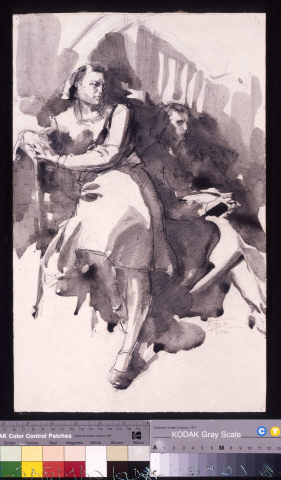

s/título

Mlle. H. L.

s/título (cabeça de homem)

Duas Pontes em Roma

C.E.P. Sepultura d’um soldado portuguêz na “Terra de Ninguém” em Neuve Chapelle (França)

Natureza-morta

sem título

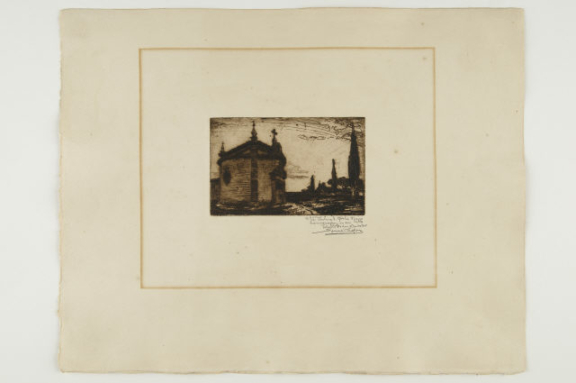

Interior de Igreja “Una Capella Desmarcos”

s/título

O Palácio da Felicidade

Italiana

s/título

Episódio do Cerco de Lisboa

Num Salão – senhora e homem encostado numa chaminé

Bruges

Episódio do Cerco de Lisboa

Mlle. H. L. dans l’atelier de Souza

Os telhados de Montmartre à noite

Três Pinheiros [Tree Pines]

Um “Traghetto”

Nazarena

Mar e Céu

s/título

No salão – retrato da senhora F.C. em vestido de noite

Barcos à vela e pessoas no cais

Noite no Canal [Night at the Channel]

Pôr-do-sol no canal grande

Praia em Portugal

s/ítulo

Num Salão – Rapaz com um arco

sem título

Pessoa sentada no Parque Monceau

s/título

Duas ordenanças de Infantaria 11

s/título

Natureza-morta

sem título

Mar e Céu [Sea and Sky]

St.Tropez

Soldados ao parapeito

A Patrulha

Natureza-morta

sem título

Flores na jarra e rosas dispersas

Mlle. H. L. com grande chapéu [Mlle H.L. with a great hat]

Untitled

Posto de socorros avançado

O episódio de 9 de Abril

Jarra com ramo de cravos

Jardim do Luxembrugo em Paris

s/título

Évora d’Alcobaça

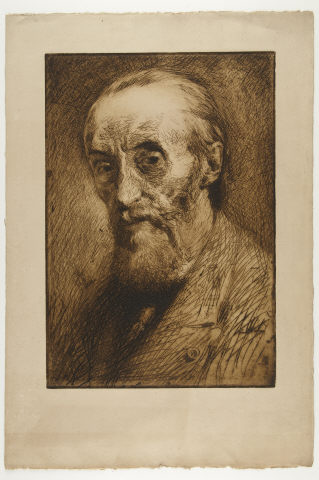

Retrato do pintor Cormon

Very-Light

Mlle. H. L. em fato de passeio

Pôr do sol

Caminho na Floresta

O Sátiro

A Brigada do Minho na “Ferme du Bois”

Vaso com pincéis, candelabro e jarra com flores

Paisagem Portuguesa

Canhão desmantelado (Le Touzet, 1918)

Num Salão – Mlle. H. L. e sua irmã