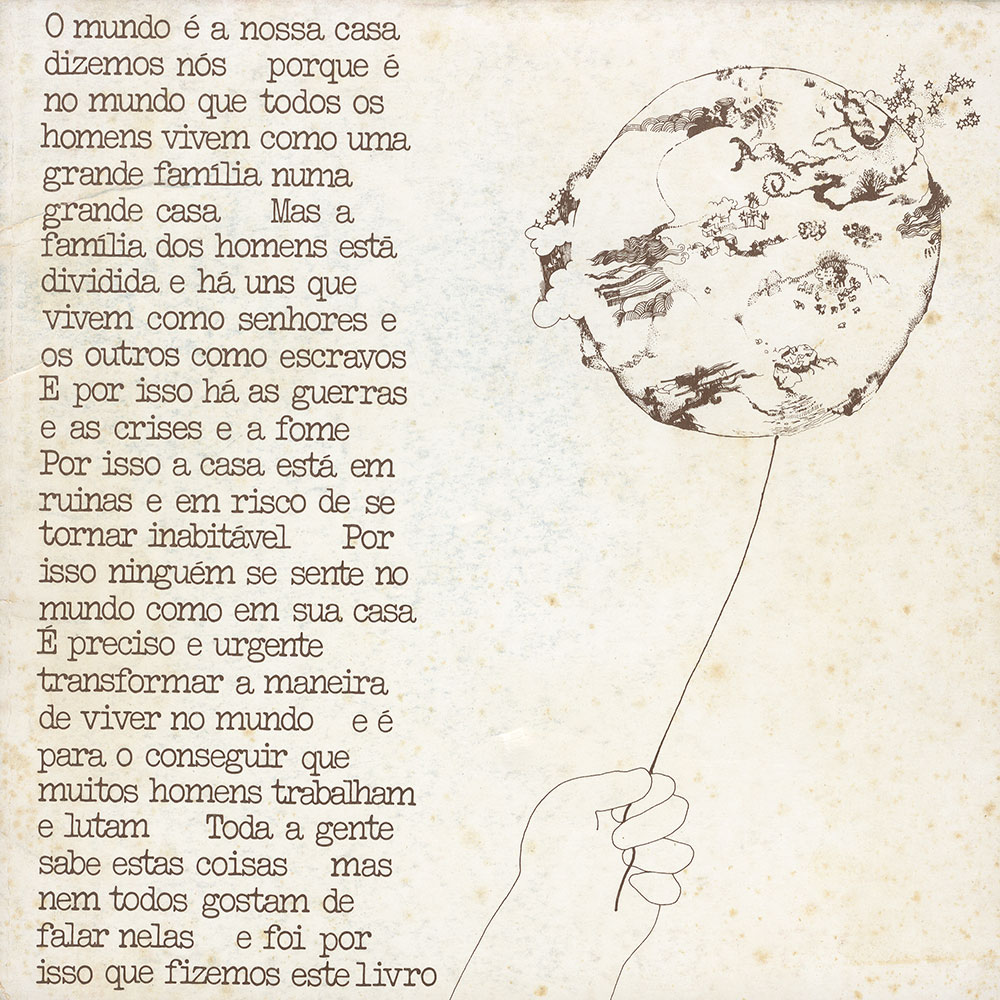

O mundo é a nossa casa

In March 1973 – between the 10th and 22nd – the 2nd Exhibition of Portuguese Design was held at the Feira das Indústrias de Lisboa (FIL) which was repeated right afterwards in Porto, at the Palácio da Bolsa.

The initiative for this exhibition, like the first (1971), came from the National Institute for Industrial Research (INII), with the collaboration of the Export Promotion Fund and the Portuguese Industrial Association.

The National Institute for Industrial Research’s Industrial Design Centre included Maria Helena Matos, Alda Rosa, Cristina Reis, Élia Pecegueiro, Margarida D’Orey and Manuel Lopes. António Sena da Silva and the Praxis co-operative were responsible for the design and direction.

Besides the exhibitors with parts whose production reflected a concern with the practice of design, there was a new section where the public was confronted with a theme which, at the time, was still little discussed among us.

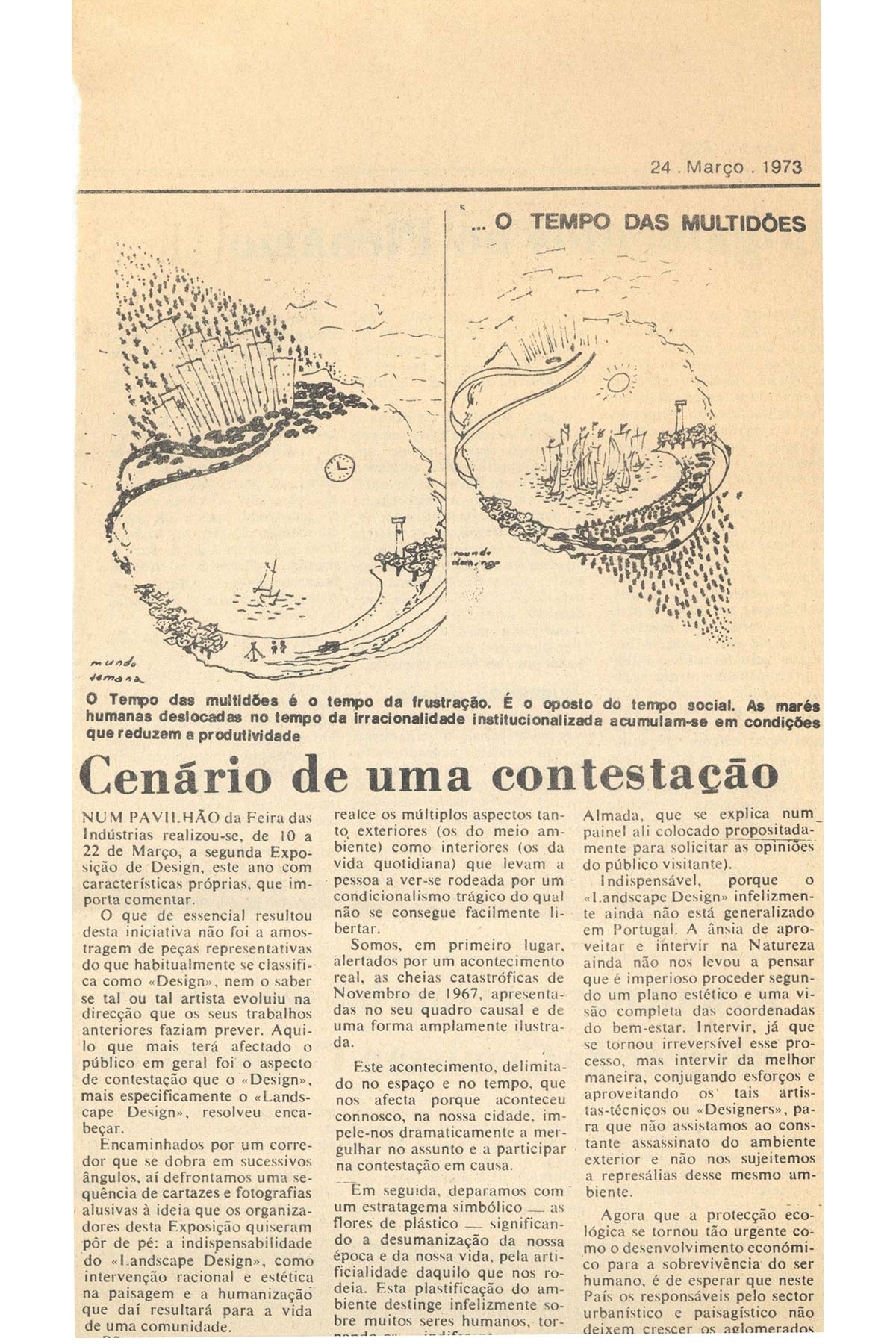

The section was called Landscape-Design and was under the responsibility of Júlio Moreira – a young landscape architect and writer – and, according to the article Cenário de uma contestação, published in the Expresso newspaper (March 24), it was the section that most affected “the general public”.

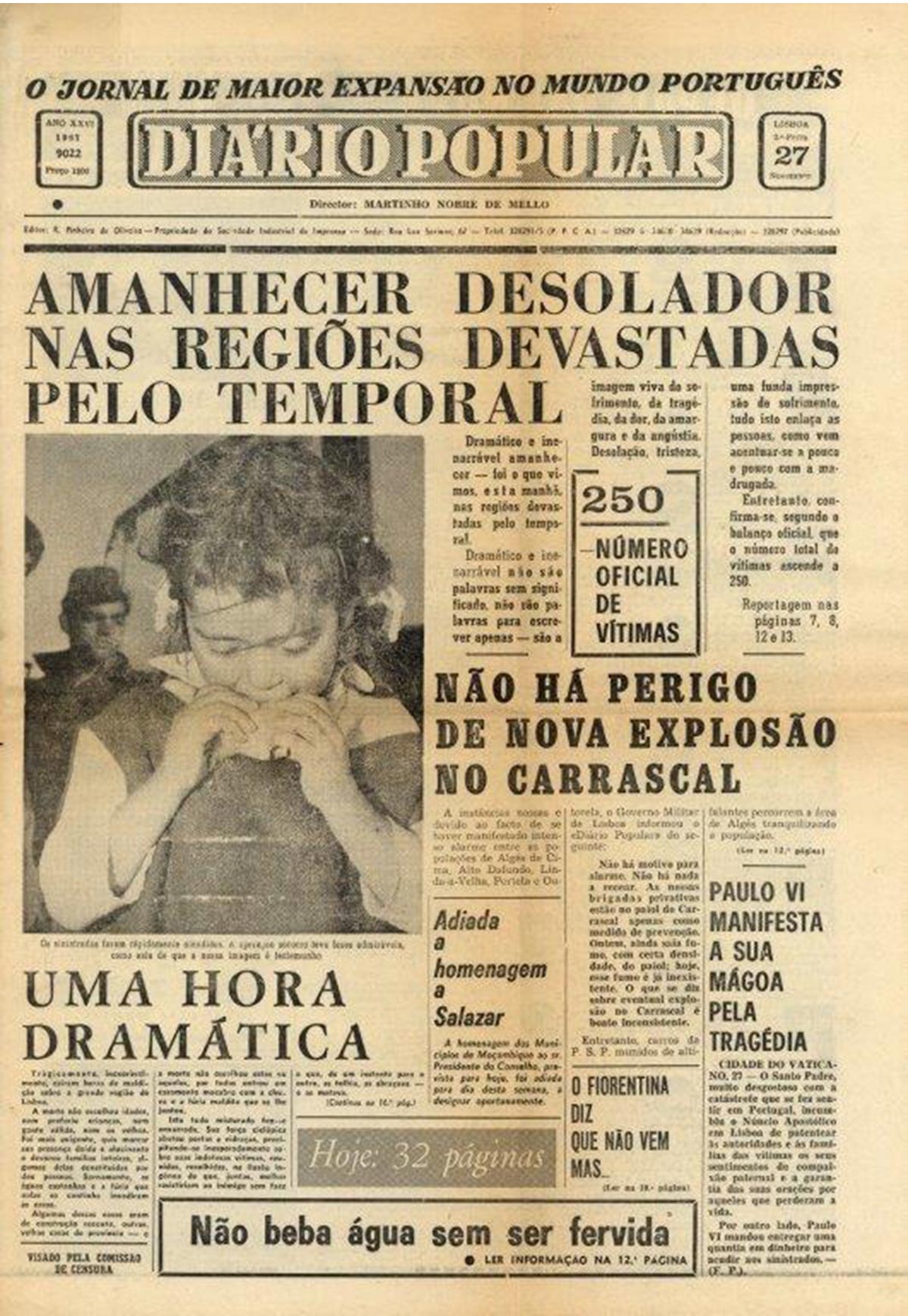

The theme was introduced in an antechamber, where visitors were confronted with large photographs of the terrible floods that devastated Lisbon and some neighbouring municipalities in November 1967. This event, which caused dozens of deaths, hundreds of displaced people, and enormous material damages, filled the front pages of the newspapers of the time before the regime cancelled it, and mobilized a wave of solidarity with the affected populations.

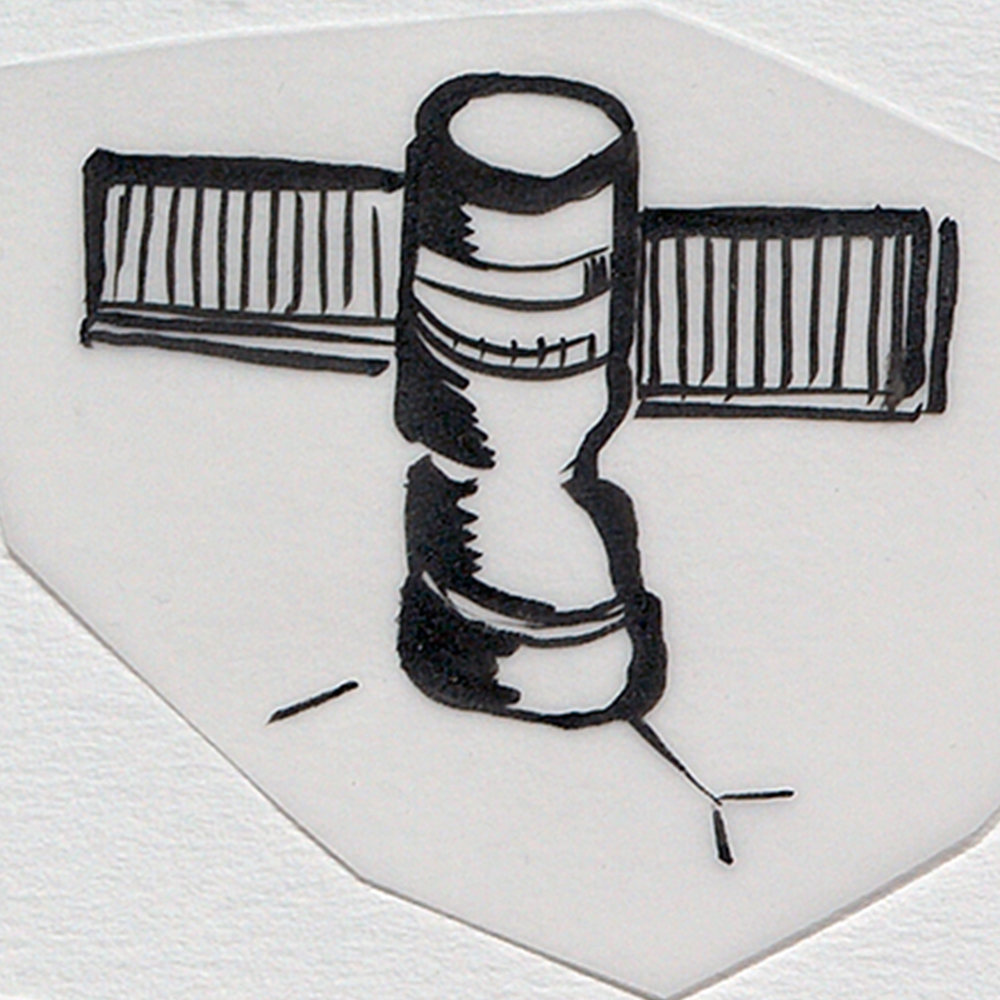

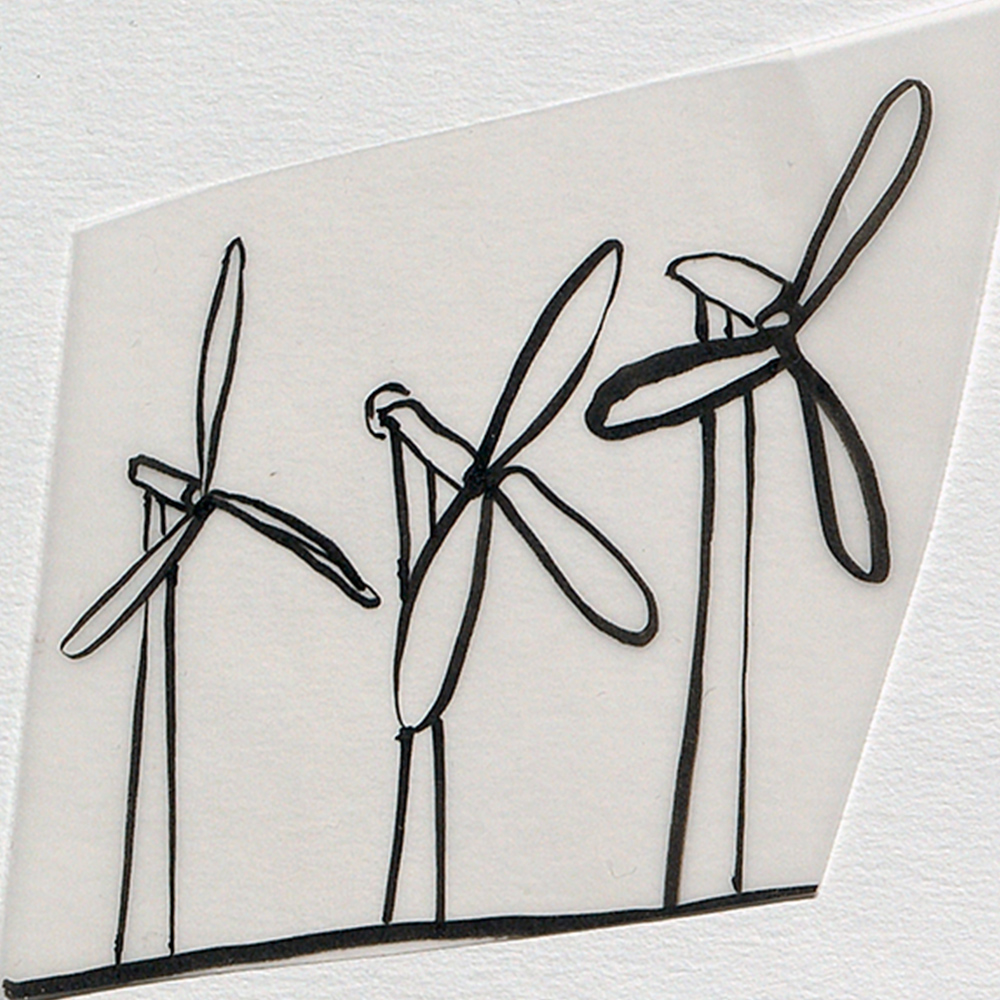

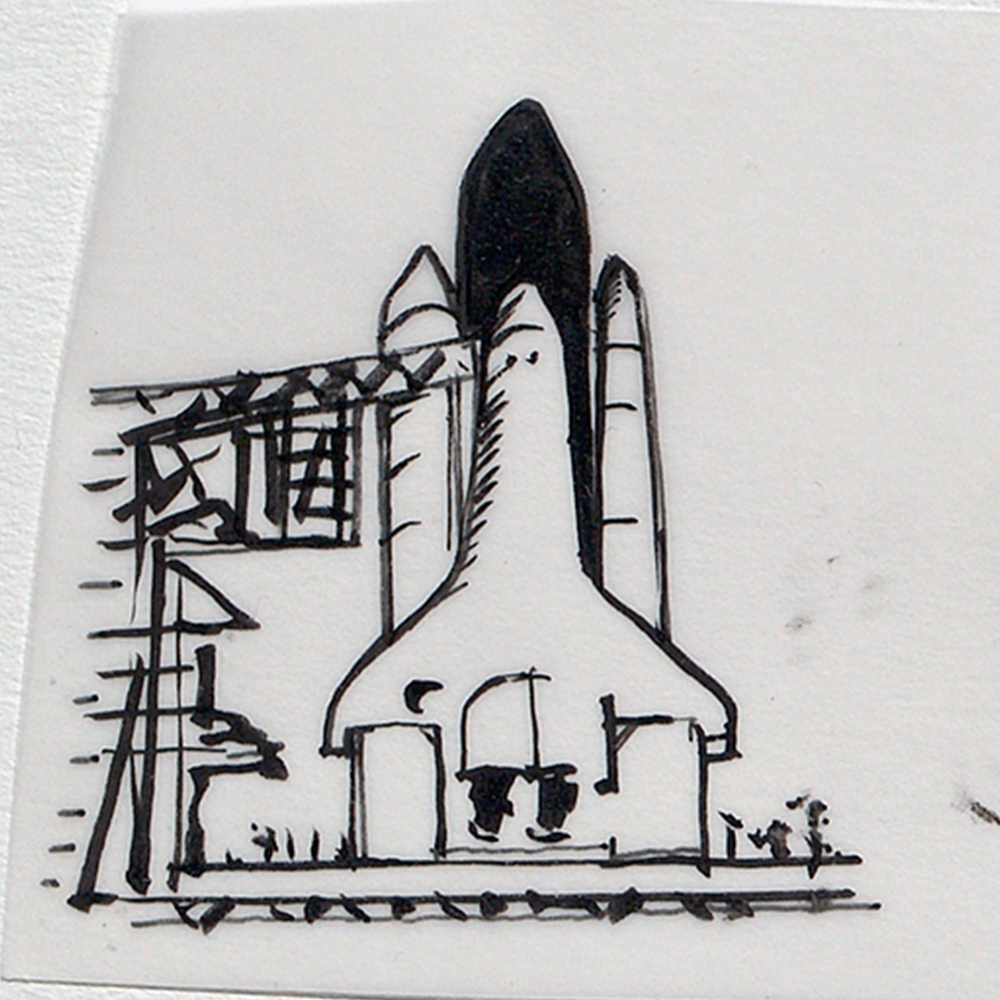

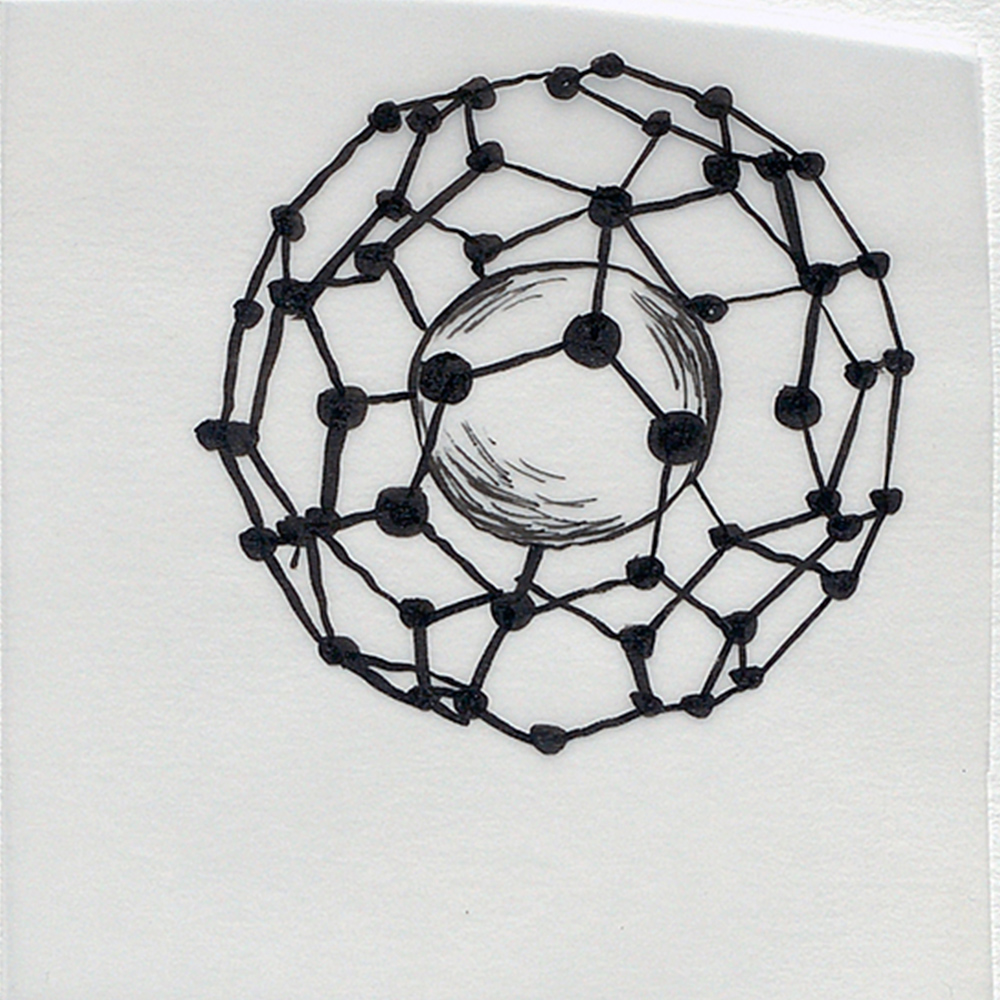

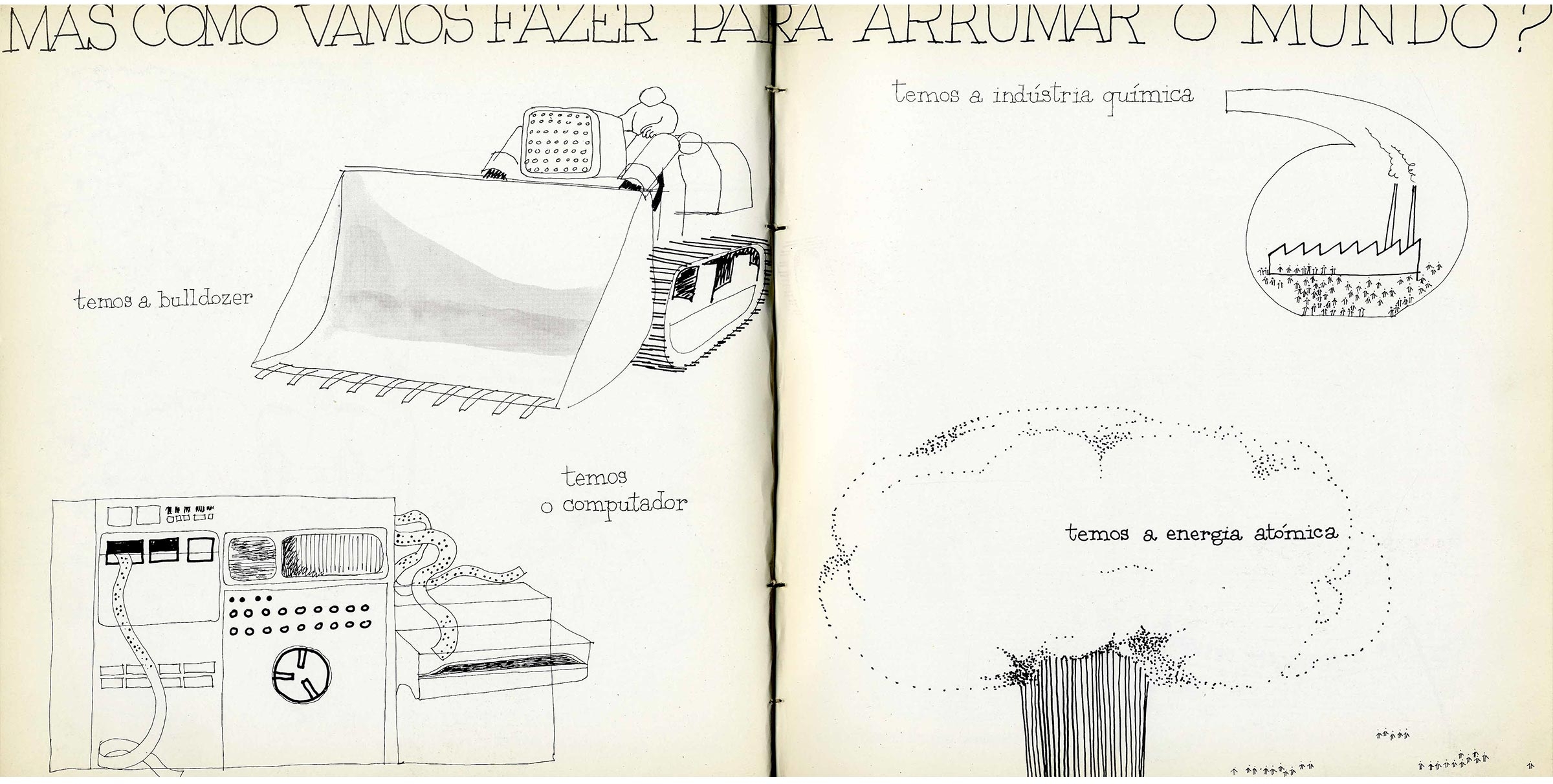

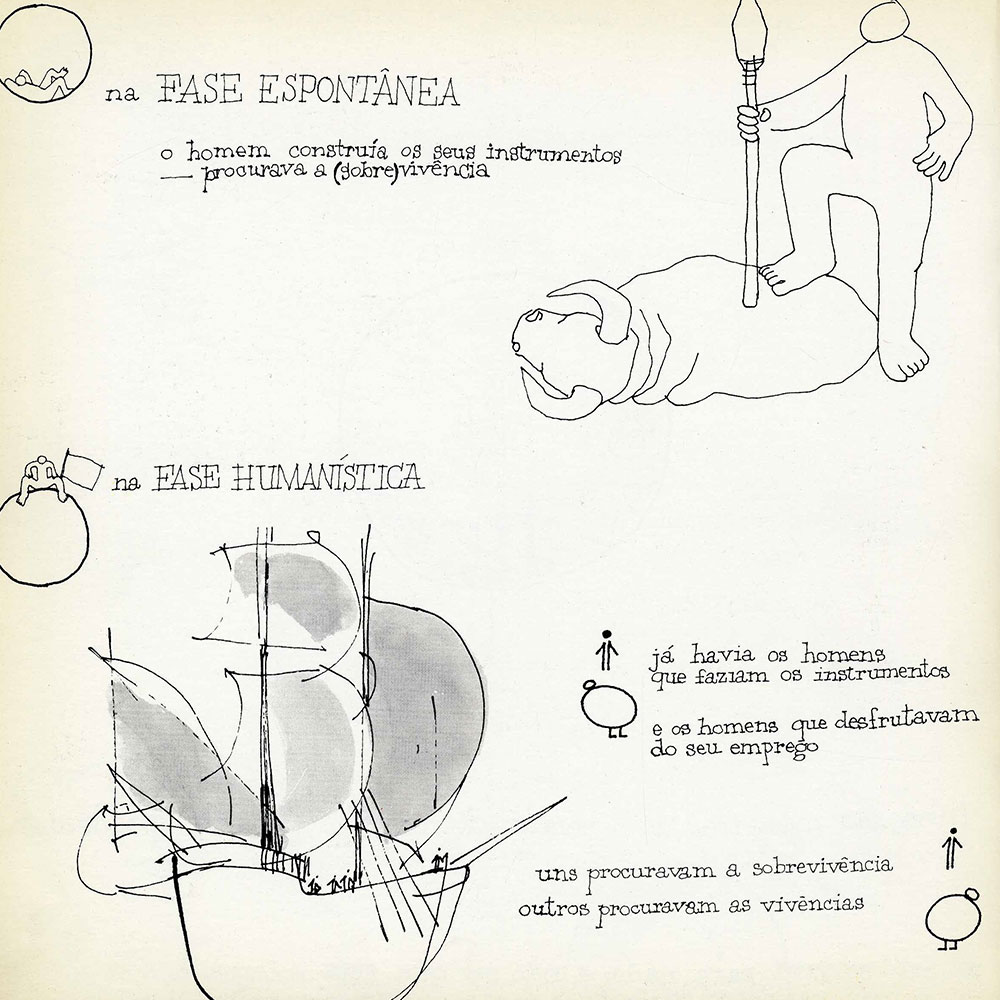

Their presence in the exhibition was intended to make the public aware of the consequences of man’s bad intervention in the environment. Then, the itinerary continued, with no detours, with schematic photographs and drawings – easy for adults and children to understand – accompanied by the texts.

Some of the press at the time did not neglect to report on the exhibition, publishing articles in which, curiously, the Landscape-Design section was given prominence. In the aforementioned article in the Expresso newspaper, we read that “Led through a corridor that unfolds in successive angles”, visitors were confronted with a “sequence of posters and photographs alluding to the idea that the organisers wanted to put into practice: the indispensability of Landscape-Design as a rational and aesthetic intervention in the landscape and the humanisation that will result from it for the life of a community”.

In turn, in one of the articles that the Diário de Lisboa dedicated to the 2nd Exhibition of Portuguese Design, this was the comment on the section:

“Instead of beautiful examples of landscape design, the visitor encounters from the outset a sequence of messages, sometimes aggressive, which commit him as a victim (and responsible) of the process of environmental degradation.

To leave no doubt (…) following a brief report of the 1967 floods, the visitor finds himself in front of a mirror, with the image of a collapsed building as a background…

The analysis proceeds along a historical and sociological path of the meaning of the environment in which we live and the life we are forced to live in it.”

This article also mentioned other aspects of the exhibition, such as its catalogue and the series of talks (called “colloquiums”) on themes for discussion about the practice of design.

One of these “colloquiums” was on the Landscape-Design section and was attended by the president of the National Environment Commission, National Institute for Industrial Research representative Maria Helena Matos, writer José Cardoso Pires, Júlio Moreira, head of the section, architect Nuno Portas, sociologist Bárbara Lopes, landscape architect Gonçalo Ribeiro Telles, architect Sena da Silva and Tomás de Figueiredo, director of the Praxis cooperative.

The República newspaper also highlighted the Landscape-Design section, quoting Júlio Moreira, who considered the section to be a testimonial, “conceived to explore the essence of the concept of design as an integrated response to the problems of well-being and survival of human groups”.

Similarly, to its predecessor, this second (and last) exhibition of Portuguese design was accompanied by an extensive and illustrated catalogue. From the Landscape-Design section, the catalogue reproduced the drawings as well as the texts that accompanied them, and which were at the origin of the book O mundo é a nossa casa (The world is our home). According to Júlio Moreira, as it was expected that the children would accompany their parents on their visit to the exhibition, the texts he wrote were short and simple, with a clear connection to the drawings by Cristina Reis.

Possibly because the content on display did in fact have some impact with the public who visited the exhibition – at the end of the tour, one of the visitors, challenged to leave his impressions on large sheets of white paper on an easel where it read “Let’s get down to action! You can write here”, he wrote: “Why not put a cover on all this and create a book?” – and because there was an obvious didactic component in it, the National Commission for the Environment asked Júlio Moreira to transform it into a book to be distributed for free in schools.

Co-edited by National Institute for Industrial Research, and written by Júlio Moreira (1930-2024), António Sena da Silva (1926-2001), Cristina Reis (1945) and Margarida d’Orey (1947), O mundo é a nossa casa (The world is our home) was finished in 1973.

Considered subversive, the copies were confiscated shortly afterwards and burnt by order of Marcelo Caetano’s government.

The reason for such a violent act of censorship does not have to do with the ecological perspective of the text, especially because Portugal was one of the countries participating in the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, held in June 1972, in Stockholm, with the theme One single Earth.

For the regime censors, the subversive character of the book resided in the way the story of the “boy who loved all things” is told, and in the reasons that led the world to become “a mess” and stop being our home.

And the world was “in a mess because some men had more than they needed” and others did not have what they needed, because some learned “more and more” and others (the majority) were never given the opportunity to learn, because there were “those who do not mind destroying everything to serve their interests… and those who are always victims of the interests of others”.

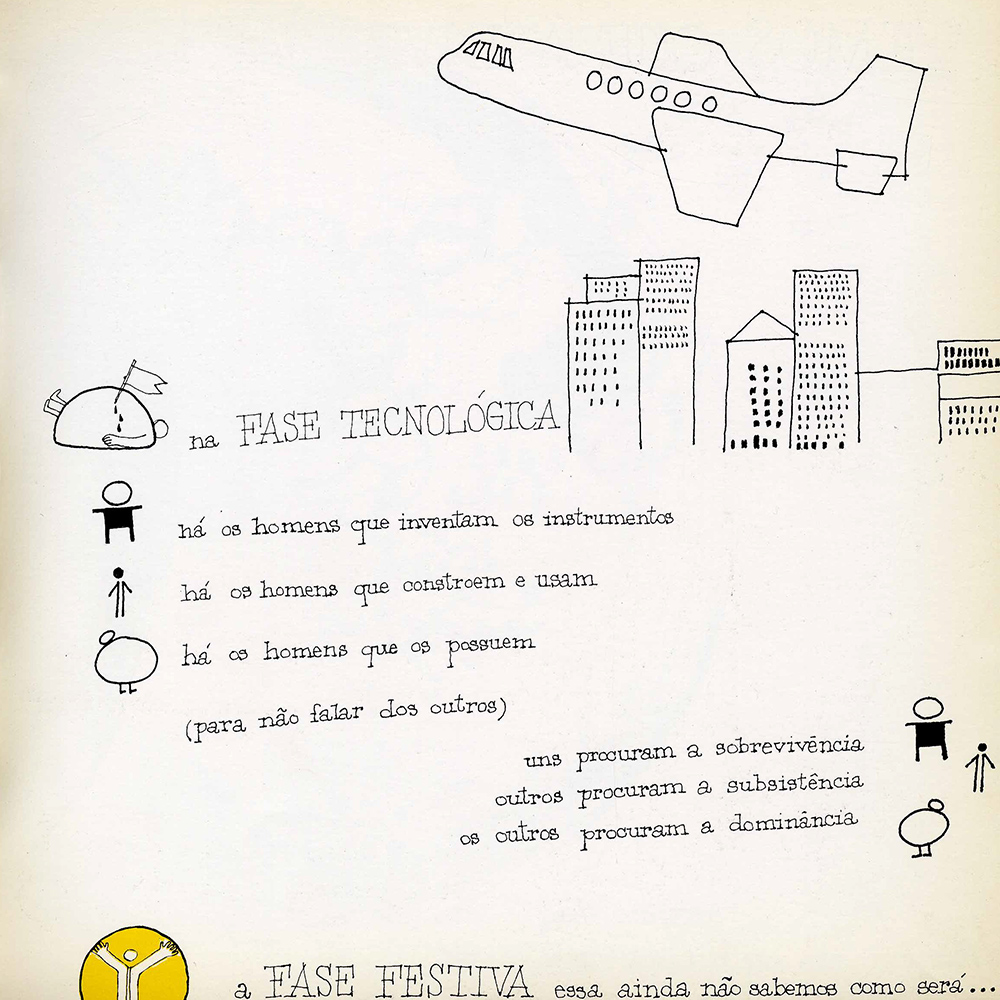

In the narrative, the relationship of the human species with the environment was also explained, an evolutionary process in four phases, two past phases – the “spontaneous phase” and the “humanistic phase” – one present, the “technological phase” – and one future – the “festive phase”. The description of the “technological phase” had a marked ideological charge, conveying a message completely opposed to the principles of the repressive regime that governed Portugal until April 25, 1974, and which it did not forgive.

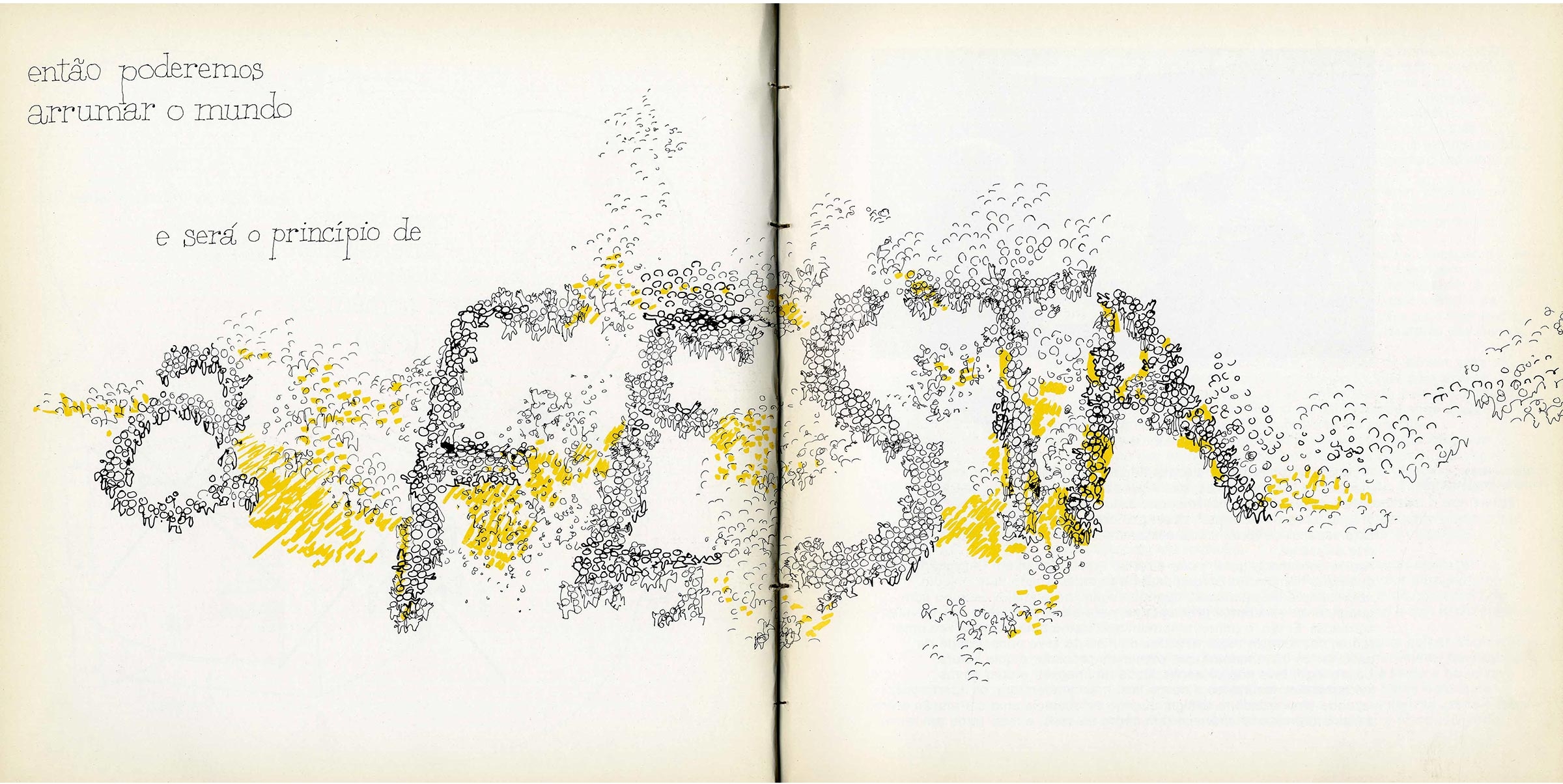

To reach the last phase, the “festive phase”, the authors predicted that it would not be easy, “because there are even those who will do anything”, they said, “to prevent it from happening, for fear of losing their privileges”, and they did not know what it would be like, but they affirmed that it was “a project that many men try to put into practice at the risk of their lives”. Finally, the children – the generations of the “festive phase” – were given some advice on how to make the world “our home” again:

“To be in balance with the world will be to know how to use things without destroying them, to build a society in which there are no hungry men, no conflicts that end in wars or other forms of violence.

And only then will it be possible to live in the world as in our home and to live our life as a Feast.”

After the 1973 edition, the book O mundo é a nossa casa (The world is our home) was published in May 1975, in a new edition that presented some differences from the previous one, starting with the cover, which set out, in a kind of poetic manifesto, the reasons why the world was ceasing to be “our home”.

Again, the responsibility of the Comissão Nacional do Ambiente (National Environment Commission), the book was distributed to schools, where it was widely appreciated: “The reaction of children and parents was surprising, and the Comissão do Ambiente received thousands of letters from children, written at home or at school”.

The good fortune of this second edition, according to the words of Júlio Moreira, led the authors – except for António Sena da Silva, deceased in the meantime – to “take up the challenge, keeping the spirit of the original edition, to adapt part of the texts and some drawings so that they can be read by today’s children”.

In fact, in the 2009 edition the ideological charge that characterised the texts of the first two editions, perfectly understandable in the political context of the 1970s in Portugal, becomes much less evident.

Fifty years have passed since the first edition of this little book. And yet, the message that O mundo é a nossa casa (The world is our home) is much more urgent today than it was in 1973, because since that decade the “mess” in our home, which is the world, has not stopped growing and the desired “festive phase” is now increasingly difficult to achieve.

The book O mundo é a nossa casa (The world is our home), as well as other material related to the Landscape-Design section and the 2nd Exhibition of Portuguese Design – press cuttings, sketches of the drawings, drafts of the texts – is part of the Júlio Moreira Collection, one of the special collections of the Art Library, donated by the landscape architect to the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in 2011.

Works from the Library

A selection of books and magazines, photographs, exhibition catalogues and other documents whose themes relate to the history of art, modern and contemporary visual arts, Portuguese architecture, photography and design.