Calouste Gulbenkian, Armenians and the political status of Jerusalem

In the aftermath of the Second World War, and in response to a request from the government of the United Kingdom, responsible at that time for Mandatory Palestine, the General Assembly of the United Nations set up a special committee for Palestine (United Nations Special Committee on Palestine – UNSCOP) in May 1947.

This committee, entrusted with the mission of drawing up a proposal with possible solutions for the region, presented a plan in September of that year, providing for the end of the British Mandate for Palestine and proposing division of the territory into two States – one Jewish and the other Arab – with the city of Jerusalem remaining under international control. This Plan was to be put to the vote as Resolution nr. 181 at the session of 29 November 1947 of the United Nations General Assembly.

The approval of this resolution and the proclamation of the State of Israel on 14 May 1948 precipitated the outbreak of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. This conflict, which spread throughout what was formerly Mandatory Palestine, was to affect the Patriarchate and the Armenian community in Jerusalem.

From Lisbon, where he was then living, Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian followed the course of events with particular concern. He had maintained lifelong links with Jerusalem and had regularly and generously supported the Armenian Patriarchate and community in the Holy City.

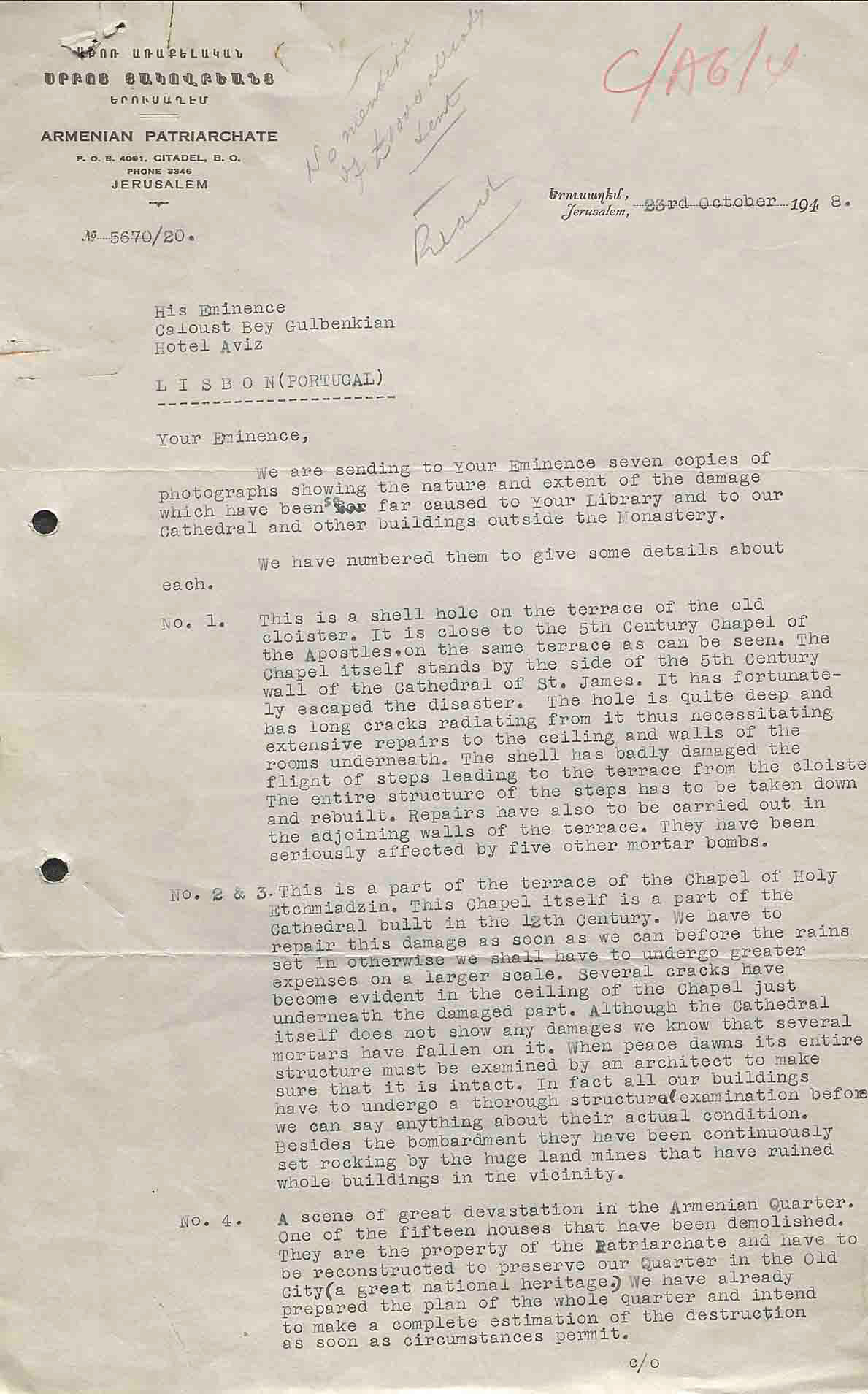

This was the context in which, in October 1948, the Armenian Patriarch of Jerusalem, Guregh Israelian (1894-1949), sent a letter to Gulbenkian describing in detail the damage caused by the war to the Armenian quarter, to the Monastery of St. James and to the Gulbenkian Library:

“The position of our Patriarchate, Monastery and Quarter rendered our buildings vulnerable to the continuous bombardment of the city so indiscriminately on a large and a small scale, a sacrilege which was unbelievable but has unfortunately been committed.”

In a dramatic account, he tells of the difficulties then faced by the Patriarchate and the Armenian community:

“(…) owing to the situation our incomes, which were derived mainly from the rents of our houses and shops in the Old City and in the new, and in Jaffa and Ramleh were entirely dried up before May and since then we have had almost no cash to pay for our current expenses and the many new expenses which the situation has created. We have curtailed the expenses of the Monastery and religious Community of St. James. We have halved the salaries of all including teachers and employees and we have suspended our constructive work except the very essential.

(…) We have had to pay all the Government and Municipal taxes for our buildings within the walls of the Old City. (…) we have had to take part in such public projects as supplying water to Jerusalem from the old sources since Jerusalem water from Jaffa has been cut since May (…)

We have had to wall up a part of our buildings for security reasons, we have had to repair and replace many windows and doors that have been repeatedly blown out of their places or smashed by the bombs and the shocks of the land mines. All the help that we have received have been spent for the feeding of the refugees (…)”

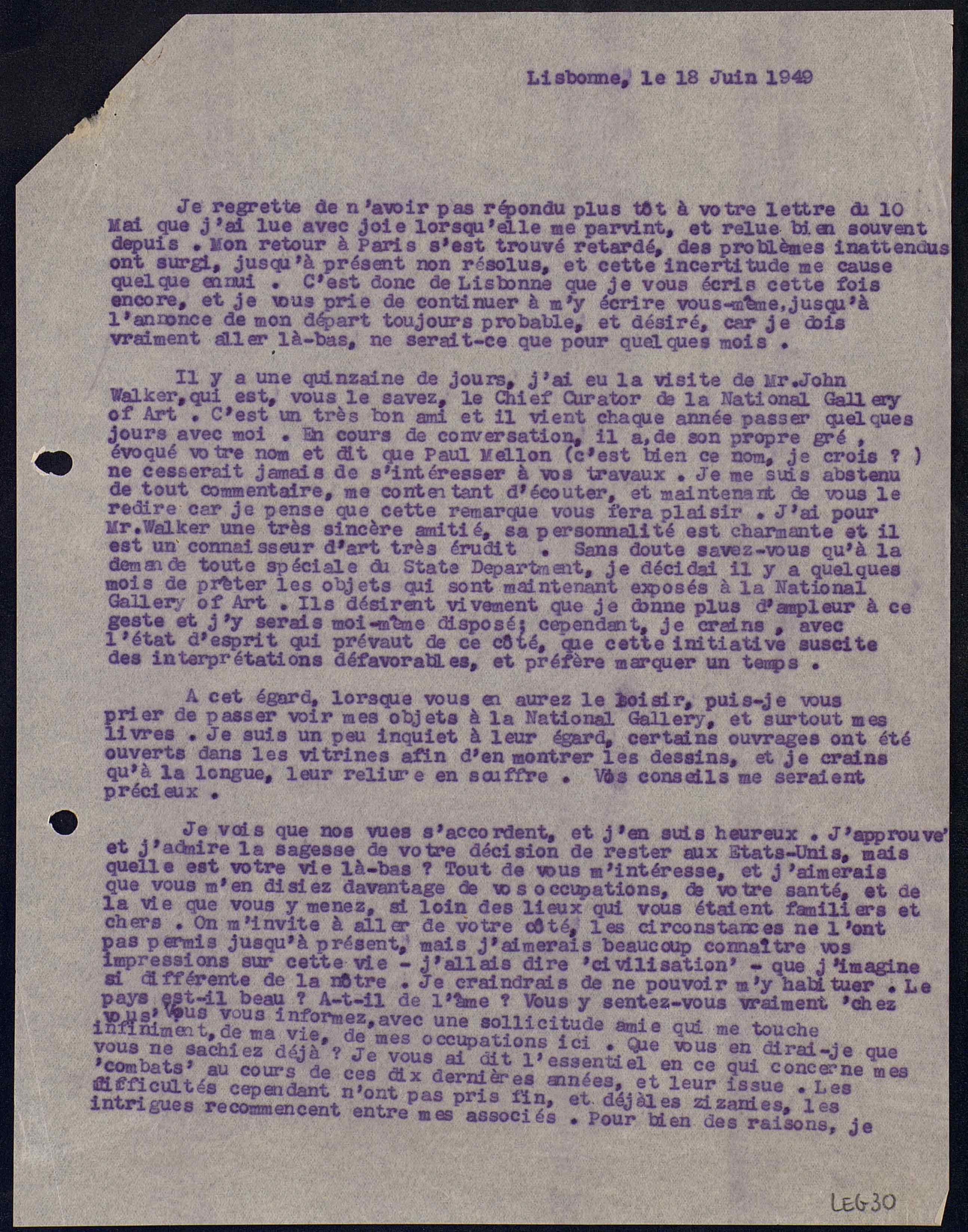

Apprehensive, Calouste Gulbenkian sought to help and influence the situation of the Armenians in the Holy Land, entrusting this task to Avetoon Pesak Hacobian (1875-1972), an Armenian who enjoyed his full trust and was at that time responsible for his offices in London. However, he was pessimistic about the prospects for resolving the conflict. In a letter sent to Alexis Léger (1887-1975) in April 1949, he writes:

“The Middle East, in which, as you know, I am deeply interested, is grappling with complete anarchy for which the great powers are solely responsible. Their ignorance of the local mindset, their incompetence, intrigues and selfishness are leading these regions into chaos. Forgive me for speaking so frankly. I would add that, in my view, the treaty between Egypt and Israel opens the door to future disturbances. As you see, I am not at all optimistic.”

In June that year, in another letter to Léger, his tone is unchanged:

“We have concerned ourselves greatly with Berlin and not enough with the Middle East, where serious problems are mounting up, along with a web of intrigue (…). Those tasked with addressing the situation are mediocre doctors, self-satisfied and, on the whole, incredibly ignorant. The President of the United States is courting Israel, inviting the president of the newly founded state to stay at the White House, and England is discreetly sending arms to the Arabs. It is all so incoherent. The mandatory States cut a sorry figure, dominated mostly by their own egotism and utterly indifferent to the fate of the countries they ought to be protecting.”

The idea that Western countries fail to understand the peoples of the Middle East, treating them with arrogance and pursuing disastrous polices centred only on their own interests, is a constant theme in Calouste Gulbenkian’s correspondence with diplomats, such as the Iranian Hussein Ala (1881-1964), the American ambassador in Lisbon from 1945 to 1947, Herman B. Baruch (1872-1953), and also with the heads of the great international oil companies, such as the American, Brewster Jennings (1898-1968).

The Arab-Israeli War of 1948 ended with the signing, during 1949, of a number of bilateral agreements between Israel and Egypt, Lebanon, Transjordan and Syria, with Israel securing an area of the former Mandatory Palestine larger than envisaged in the United Nations plan for division of the territory.

The city of Jerusalem, which had been partially captured by Israeli troops during the war, came under the control of Israel (western part) and Transjordan (the eastern part, which included the Old City and the Armenian quarter). Nonetheless, the United Nations Trusteeship Council pressed ahead with efforts to implement Resolution nr. 181 of the United Nations, which provided for division of the region into two states, and international control of the city of Jerusalem.

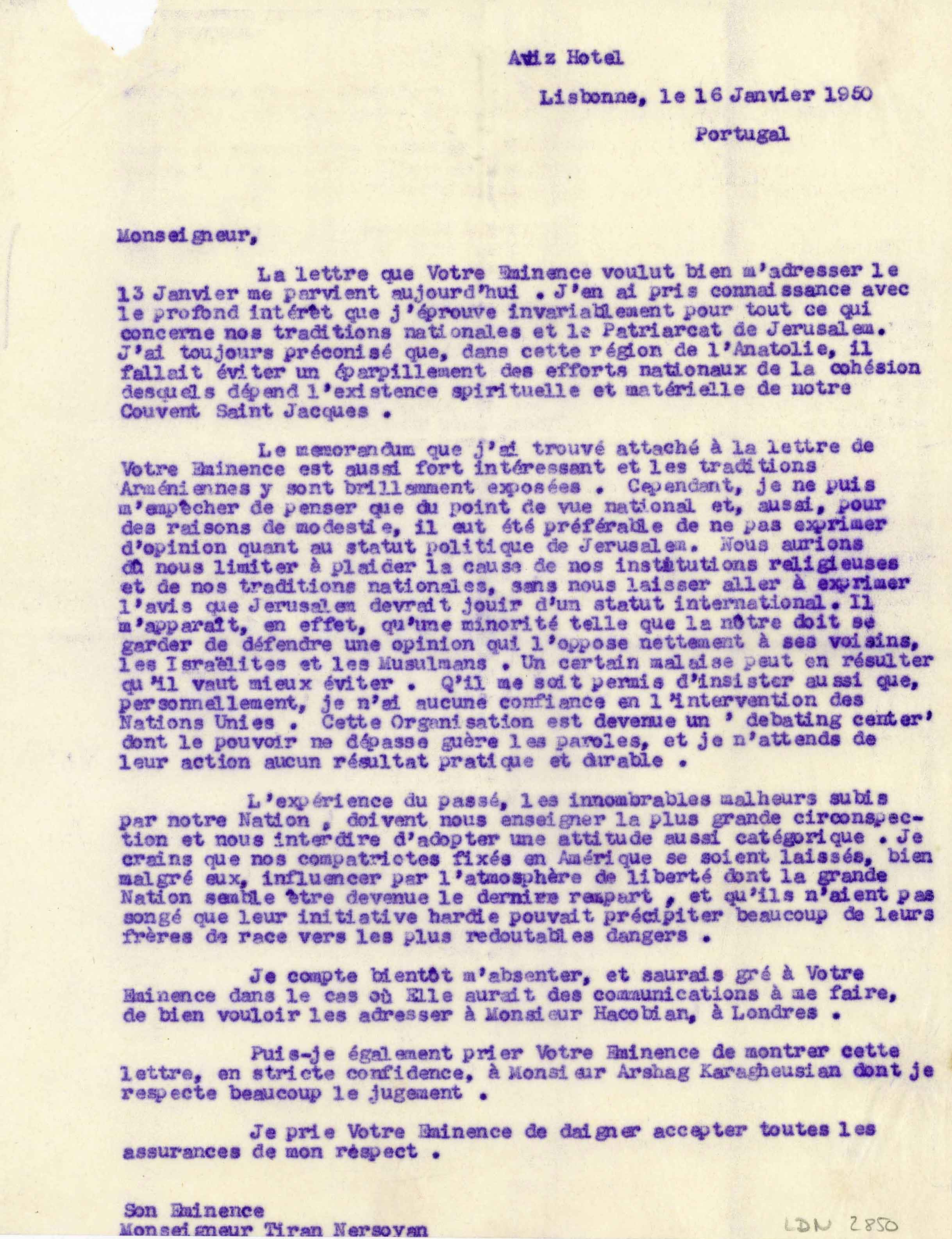

In January 1950, the bishop Tiran Nersoyan (1904-1989), head of the Armenian Church in North America, was entrusted by the Locum Tenens of the Patriarch of Jerusalem with submitting the Patriarchate’s position on the future status of the city to the Trusteeship Council. He wrote to Calouste Gulbenkian, attaching a copy of the memorandum he planned to send to the Council, which was shortly to meet in order to consider the status of Jerusalem.

The document asserted the support of the Armenian Church, through the Patriarchate of Jerusalem, for the United Nations resolution in favour of international control of the city. The bishop argued that, in view of the international character of the Holy Places for the three main world religions, it would be advantageous for the city not to be governed by a single nation or regime, but for free access to the Holy Places to be safeguarded by an international authority.

In reply, Calouste reiterated his view about the need not to lose sight of the central issue for the Armenian community, which was to ensure the spiritual and material survival of the Convent of St James, the seat of the Patriarchate, and was very cautious on the question of Jerusalem’s political status:

“From a national point of view, and also for reasons of prudence, it would have been preferable for us not to have pronounced on the political status of Jerusalem. We should have limited ourselves to defending the cause of our religious institutions and our national traditions, without allowing ourselves to express the opinion that Jerusalem should enjoy international status. I think that, as a minority, we should have taken care not to defend an opinion that clearly sets us against our neighbours, the Israelis and the Muslims. It might give rise to bad feeling, which is best avoided. Permit me also to stress that, personally, I have no confidence whatsoever in the intervention of the United Nations. The United Nations has become a debating centre with little power other than that of words.”

The Armenian Church’s position was presented formally to the United Nations Trusteeship Council, meeting in Geneva, in February 1950, by the bishop Tiran Nersoyan.

The cleric started by recalling the links between the Armenian people and the Holy City, dating back 1,300 years, stressing that Jerusalem stands at the centre of Armenian religious life, but toned down his discourse as regards support for the international status of the city.

He said he had no intention of expressing political opinions on the complex issue of Jerusalem, but that all his arguments started out from the assumption that Jerusalem would be placed under international administration, as envisaged in the United Nations Resolution.

He added that the current situation, in which Jerusalem was governed by Jews and Arabs, was unfair to Christians, arguing that the city should be united and not be divided, as it belongs to the three great religions.

He also suggested that the concept of protection for the Holy Places be used in a broader sense and include religious buildings, educational establishments and monasteries.

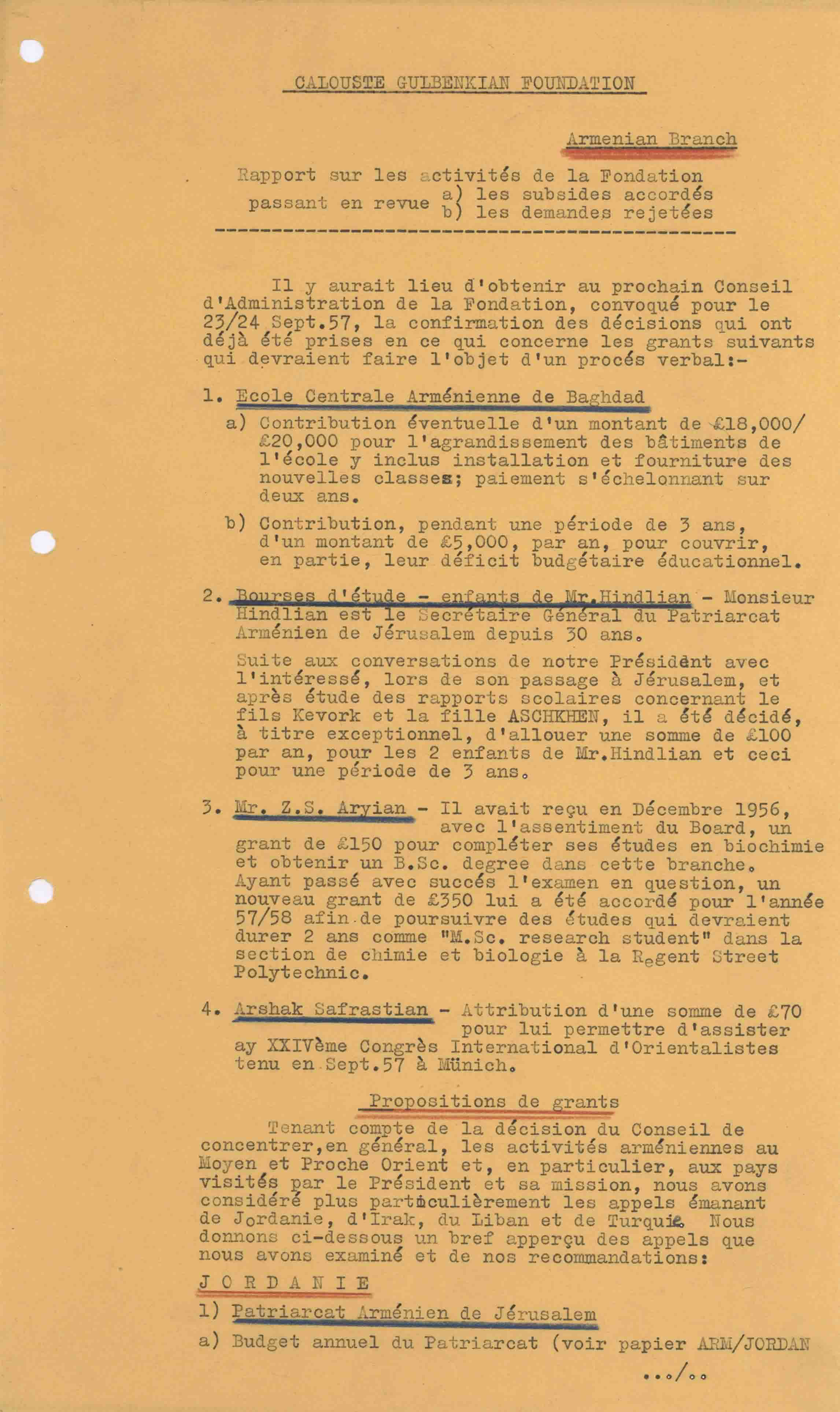

Calouste Gulbenkian, who followed the process of making representations, through Hacobian, let it be known to the acting Patriarch, the Reverend Yeghisé Vardapet Derderian (1911-1990), that he was aware of the difficult situation facing the Patriarchate, deprived of the rental income from its properties in Jaffa and Jerusalem, and asked for detailed information about those properties in order to decide how best to help.

In January 1952, more than a year after this request, Calouste was informed, by a memorandum sent by his offices in London, of the current situation of the Patriarchate’s properties in Israel. He learned that talks were under way with the Israeli authorities, and that part of the rental income from the Patriarchate’s properties was again being paid, although there were some constraints on transferring money to the Old City of Jerusalem, then under Transjordanian administration. The financial problems nonetheless continued, due to the wider situation created by the conflict.

Calouste Gulbenkian continued until the end of his life to provide financial support to the Armenian Patriarchate in Jerusalem. Thereafter, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, recognising the importance of the Patriarchate to the Armenian community, was to continue to aid the Patriarchate to this day.

From the Archives

Significant moments in the history of Calouste Gulbenkian and the Gulbenkian Foundation in Portugal and around the world.