Books censored and banned by the Estado Novo

Censorship of professional activities related to the country’s intellectual and cultural production was consolidated in 1933, through Decree-Law nr. 22,469 of 11 April of that year, the date on which the Political Constitution of the Portuguese Republic came into force, a document that guaranteed the political and ideological principles of the Estado Novo.

While Article 1 ensured “the expression of thought by means of any graphic publication, under the terms of the press law and those of this decree”, Article 2 stated that “periodical publications as defined by law, as well as flyers, leaflets, posters and other publications, whenever any of them deal with matters of a political or social nature, were still subject to prior censorship.”

“Art. 3 Censorship shall have the sole purpose of preventing the perversion of public opinion in its function as a social force and shall be exercised in such a way as to defend it against all factors that may lead it astray against truth, justice, morality, good administration and the common good, and to prevent the fundamental principles of the organisation of society from being attacked.”

— Diário do Governo nr. 83/1933, Series I of 1933-04-11

From 1933 until 25 April 1974, many authors had their works censored, banned, and confiscated by the agents of the censorship commissions that existed throughout Portugal’s mainland and overseas, subordinated to the General Directorate of Censorship Services, created in 1933, and its successor, the Directorate of Censorship Services (1935), assisted by PIDE, the regime’s political police.

No area of knowledge escaped the scrutiny of the censors’ blue pencil and red stamp: from the fine arts to the natural sciences, political science, economics, education, geography, as well as philosophy, history, literature, music, sociology, and religion. Between 7,000 and 10,000 books, by Portuguese and foreign authors, in original editions or translations, passed through their eyes and hands, listed in the 10,000 or so reading reports produced by the various commissions between 1934 and 1974.

The classification of subversive content, undesirable and capable of corrupting public opinion against the “fundamental principles” of the regime, fell entirely within the intellectual capacities and discernment of each censor and sometimes simple, apparently innocuous words, such as red, led to associations that attested to the work’s dangerousness.

On the other hand, the range of topics that could fall under these classifications went far beyond politics, although the censors paid particular attention to matters of possible communist and anarchist inspiration. In a country subject to the “God, Homeland and Family” trilogy, other themes considered to be offensive to morals and good customs, erotic and/or pornographic, and against the Catholic religion, also had little chance of being approved.

While in the case of the press, plays, films and, later, television, the content was examined beforehand, in the case of literary works, censorship usually took place after publication, with the confiscation of the edition and a ban on new editions.

Foreseeing possible failures, in 1943 the Ministry of the Interior issued a decree-law that passed the burden of responsibility on to publishers and distributors, as well as providing for the possibility of “government delegates” on their offices.

“(…) view of the inconveniences to the book trade itself that would result from the prior official reading — necessarily lengthy — of all works, it will be necessary to continue and demand from those involved in their printing, distribution and sale their share of the responsibility.”

“Art. 2 Whenever any writing is published, edited, re-edited, sold or distributed that is harmful to the fundamental principles of the organisation of society or detrimental to the defence of the higher purposes of the State, the Minister of the Interior, (…) may order those delegates of the Government work with the companies responsible, and at their expense (…)”

— Diário do Governo nr. 185/1943, Series I of 1943-08-30

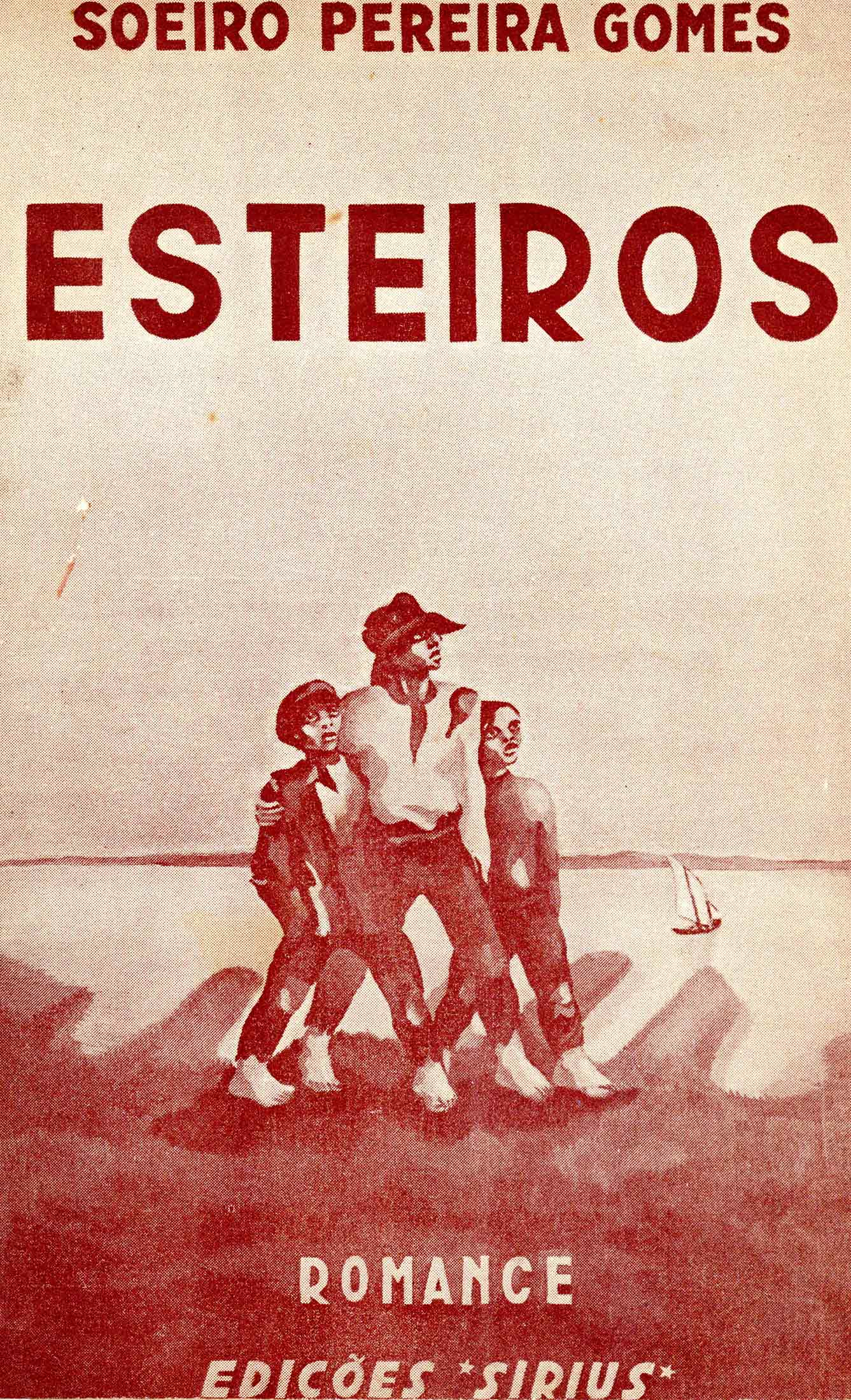

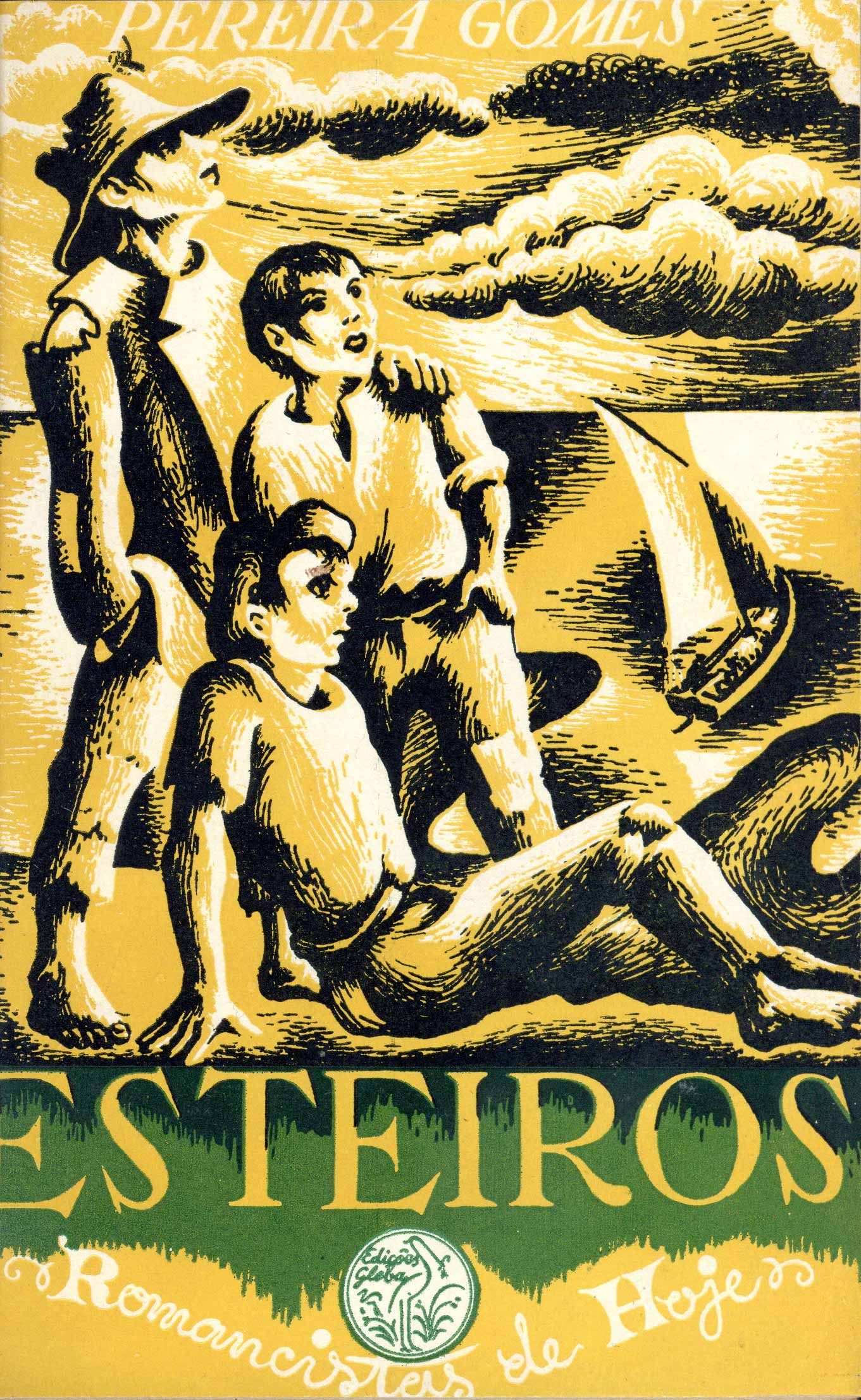

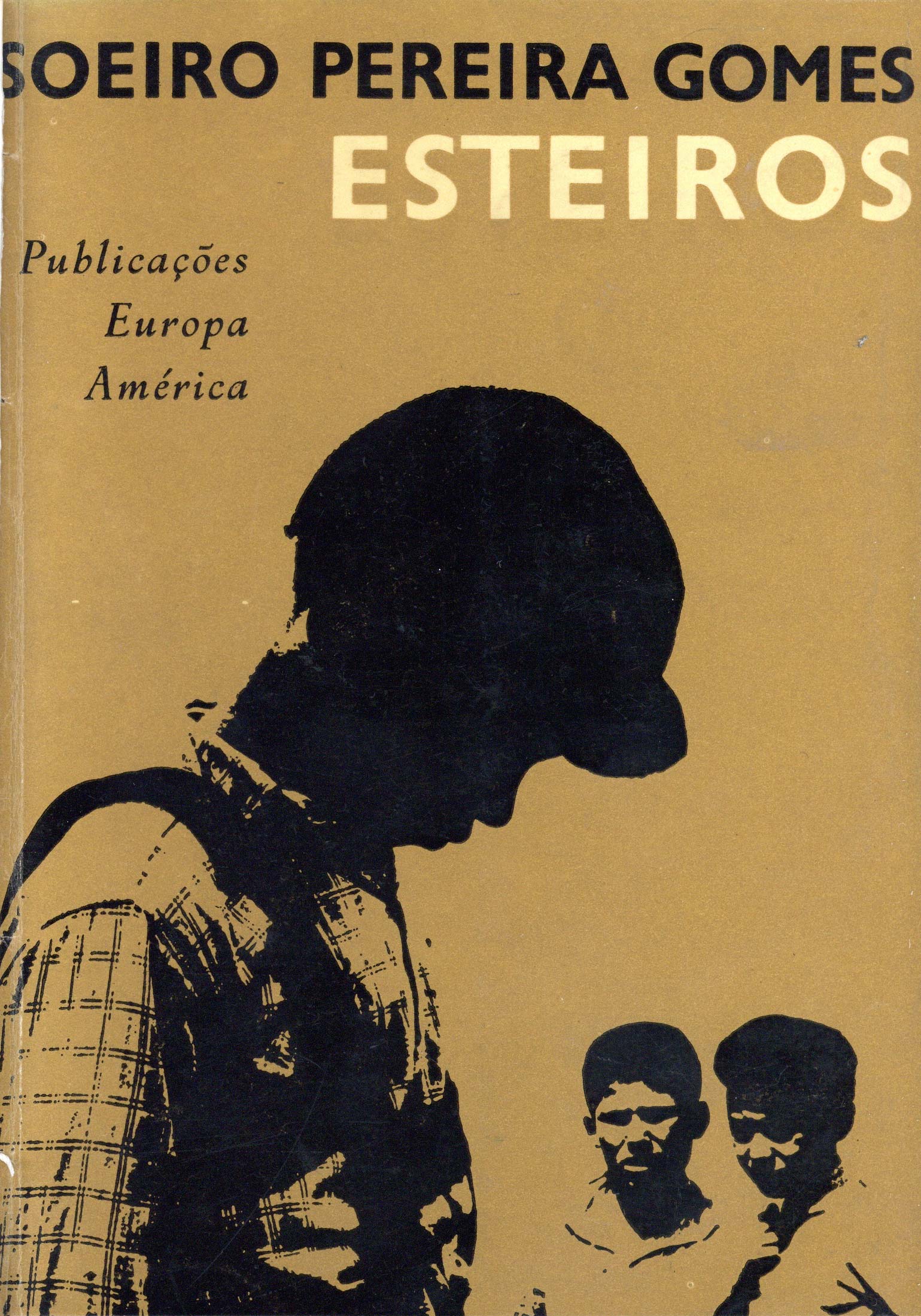

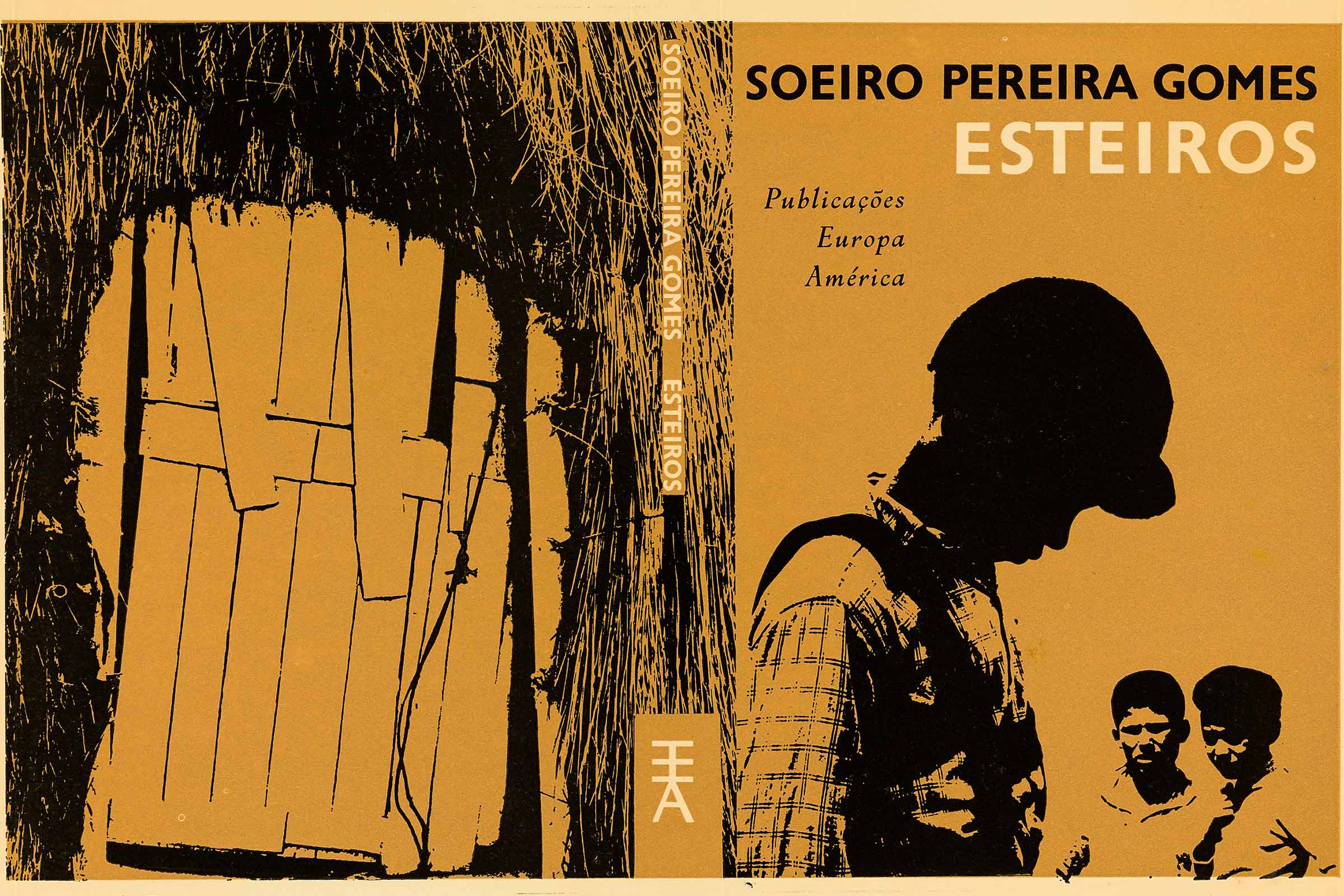

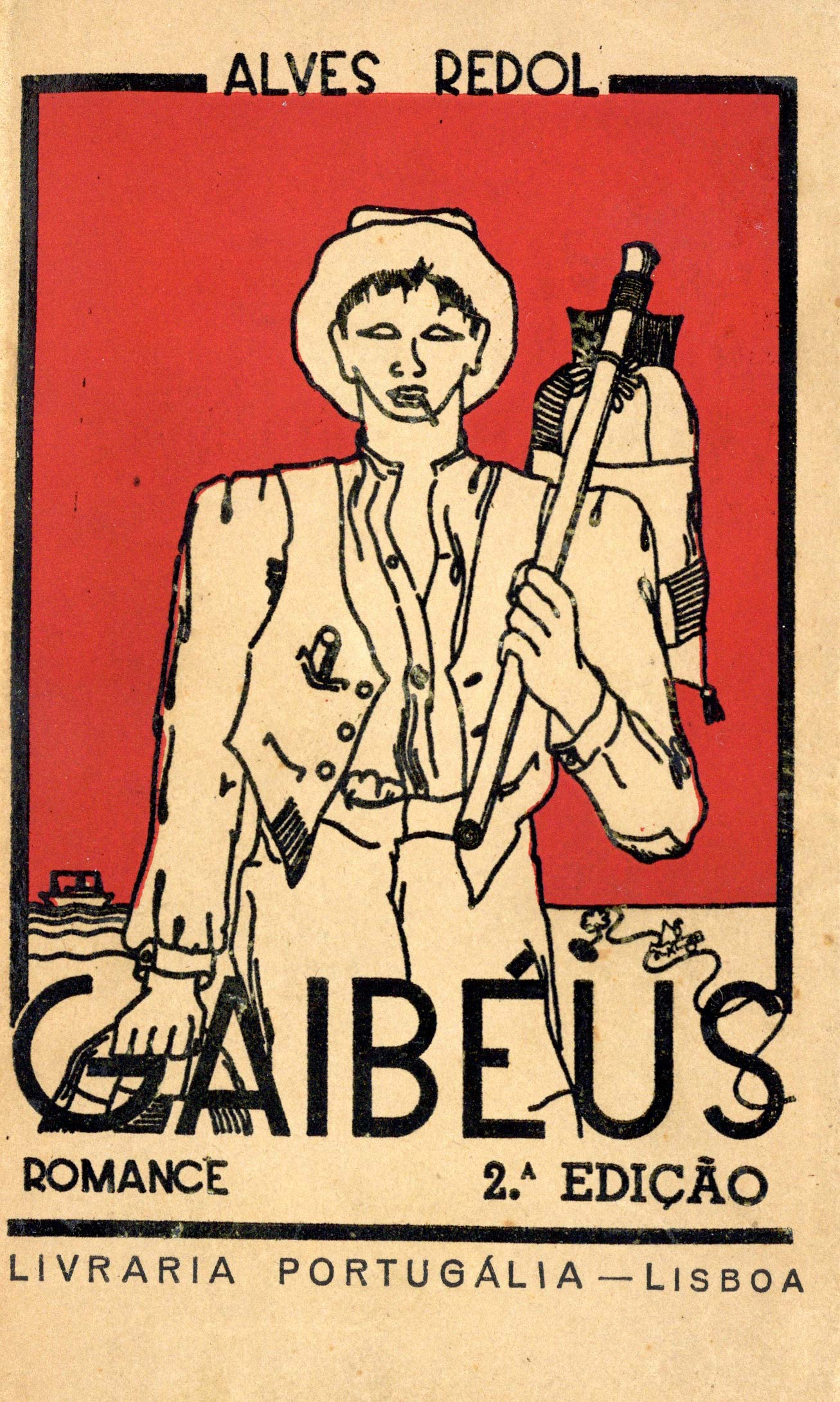

This legal provision did not, however, prevent works banned after the first edition from being published in second, third and more editions. There were also books that only came to the attention of the censors after several editions and ended up not being banned so as not to give them prominence. This was the case with Esteiros by Soeiro Pereira Gomes (1909-1949), with a cover and drawings by Álvaro Cunhal: the first edition was authorised in 1941, (re-edited in 1942, 1962 and 1971), but was the focus of a contrary opinion in 1966.

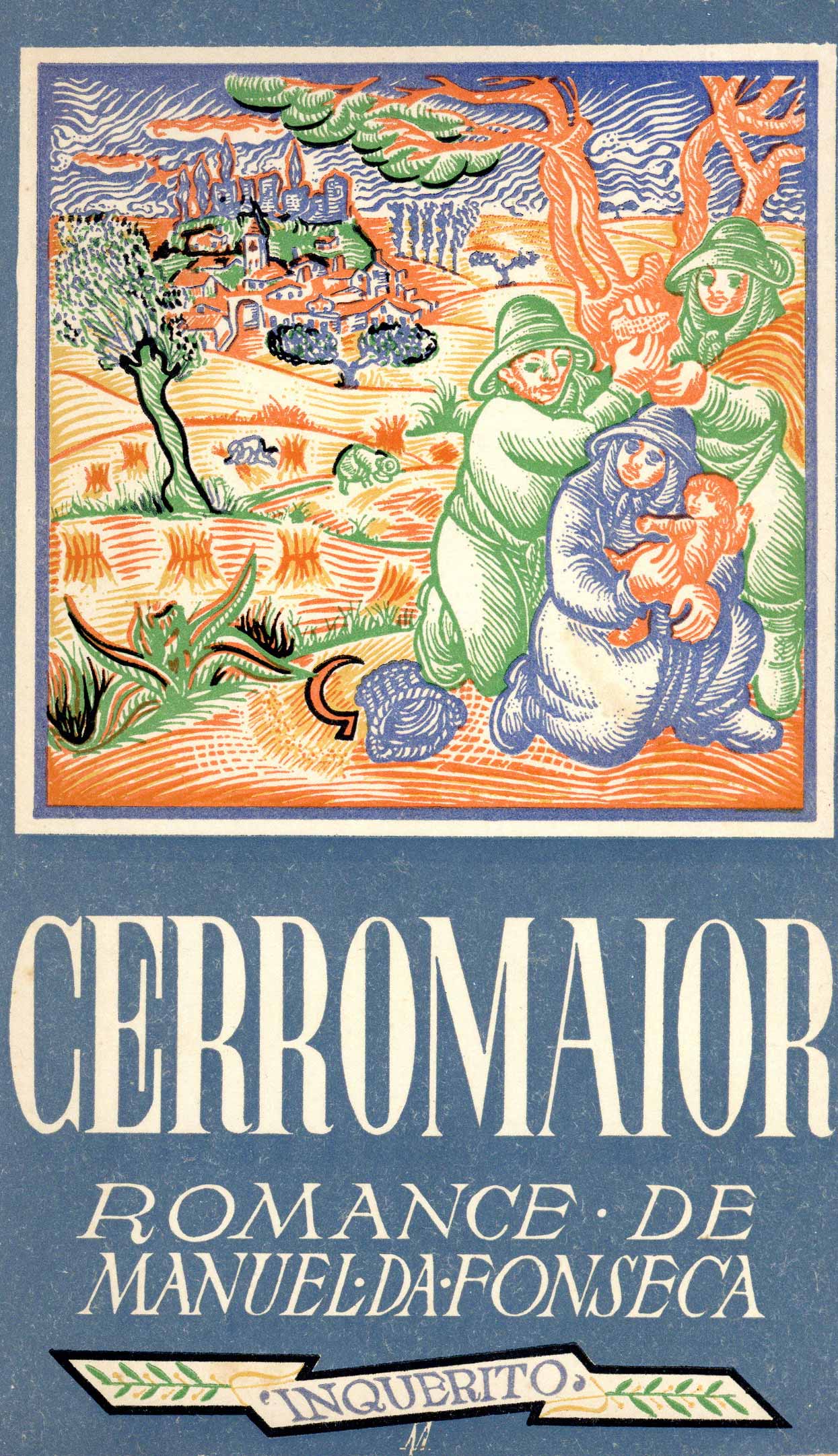

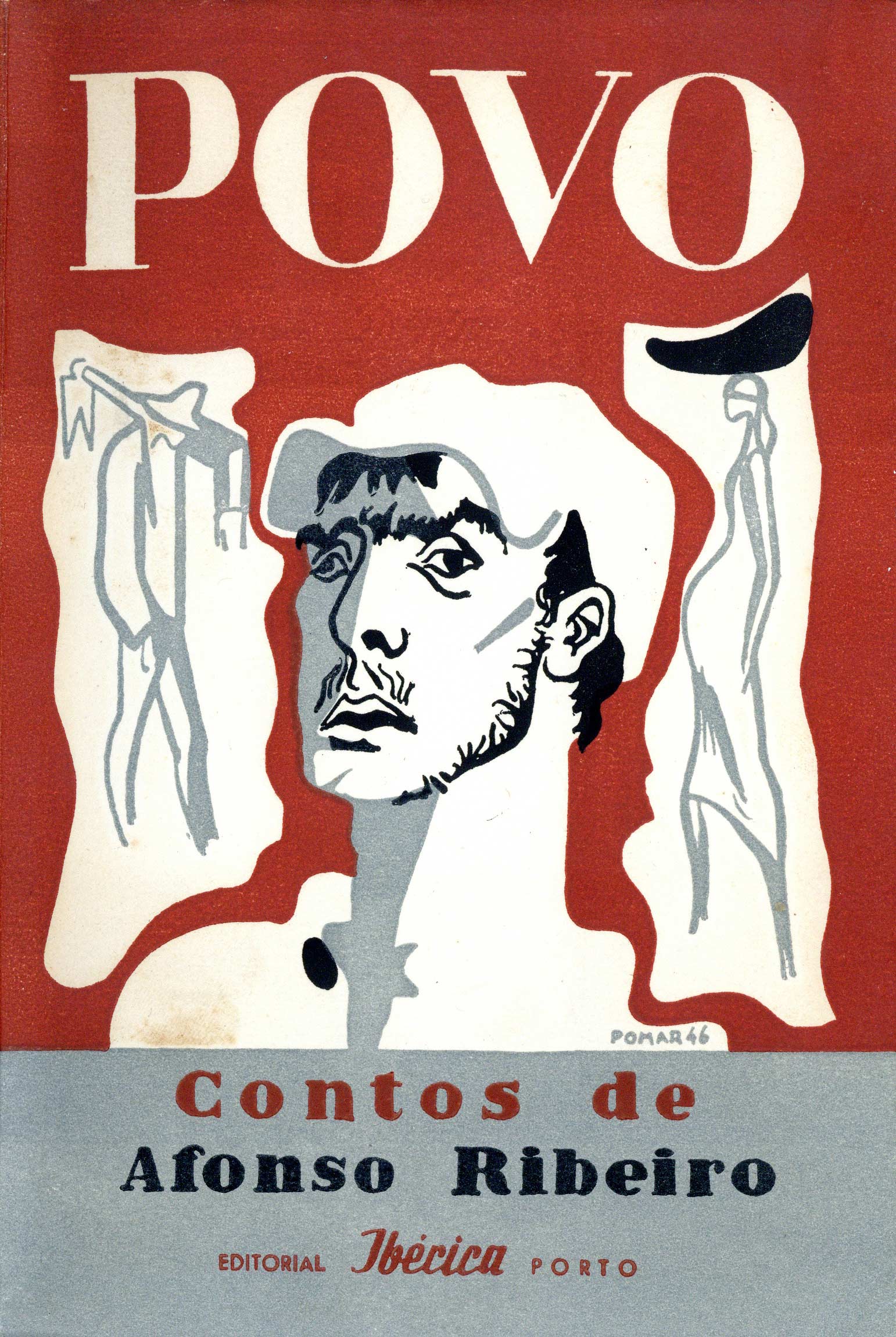

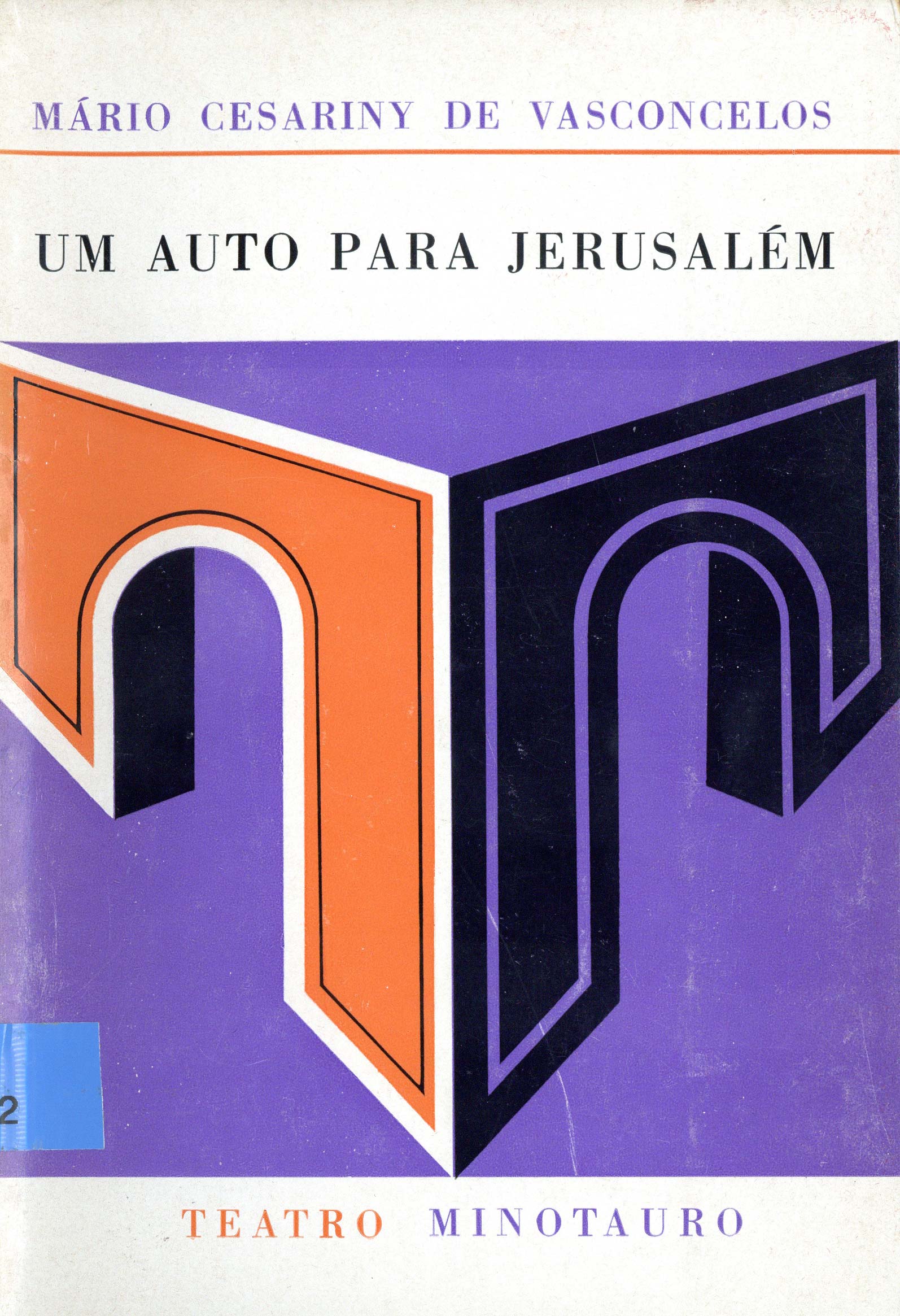

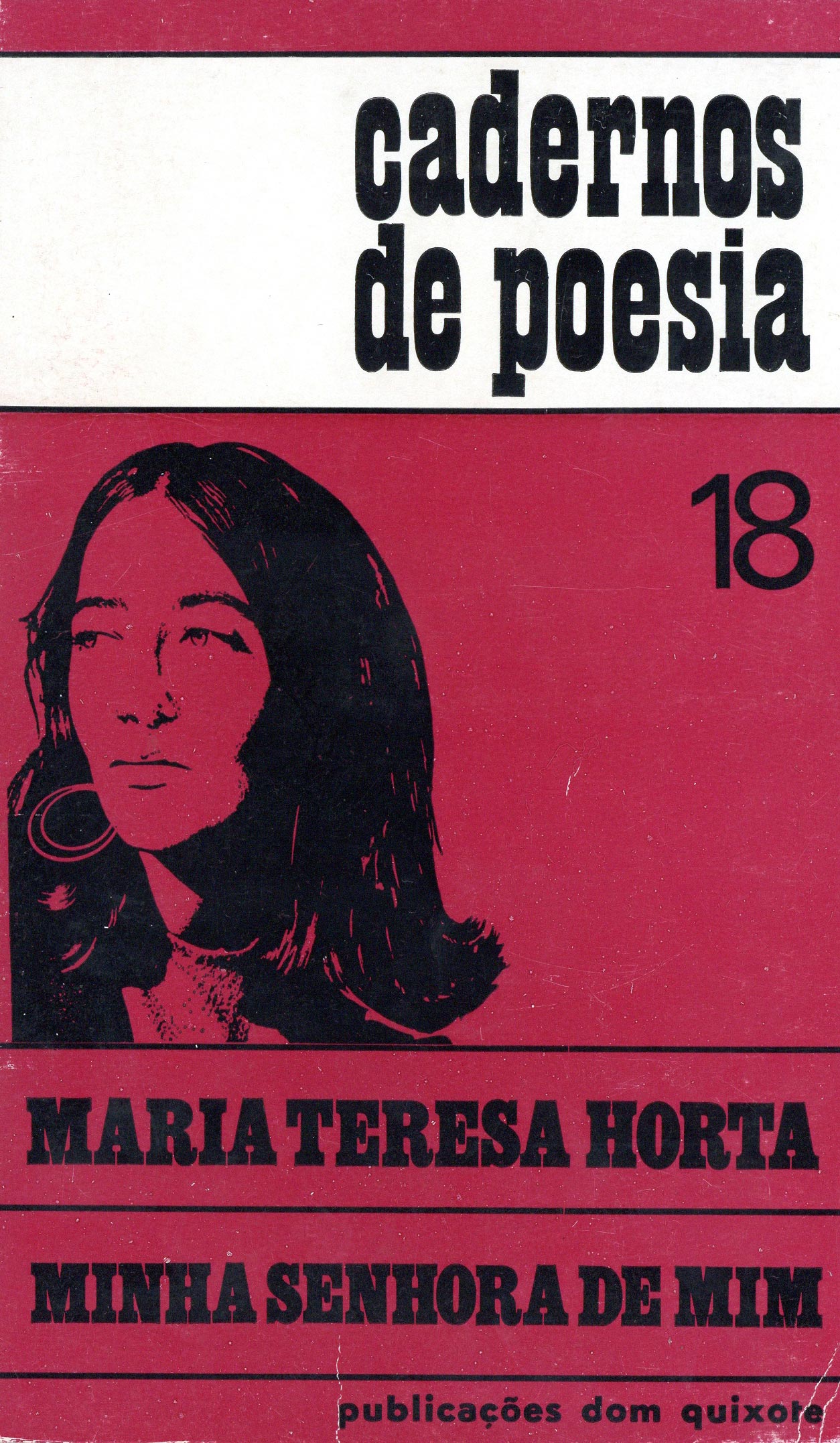

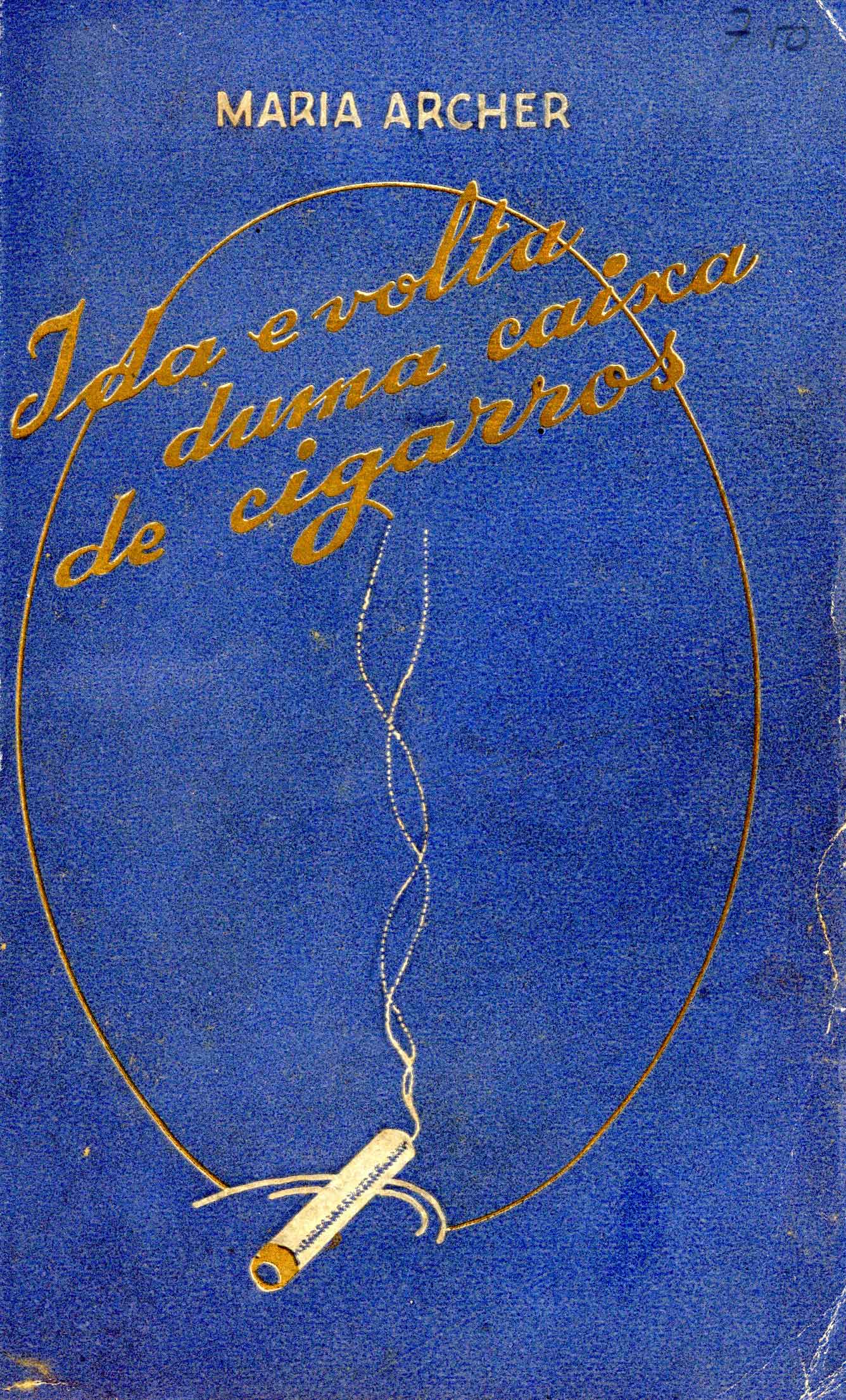

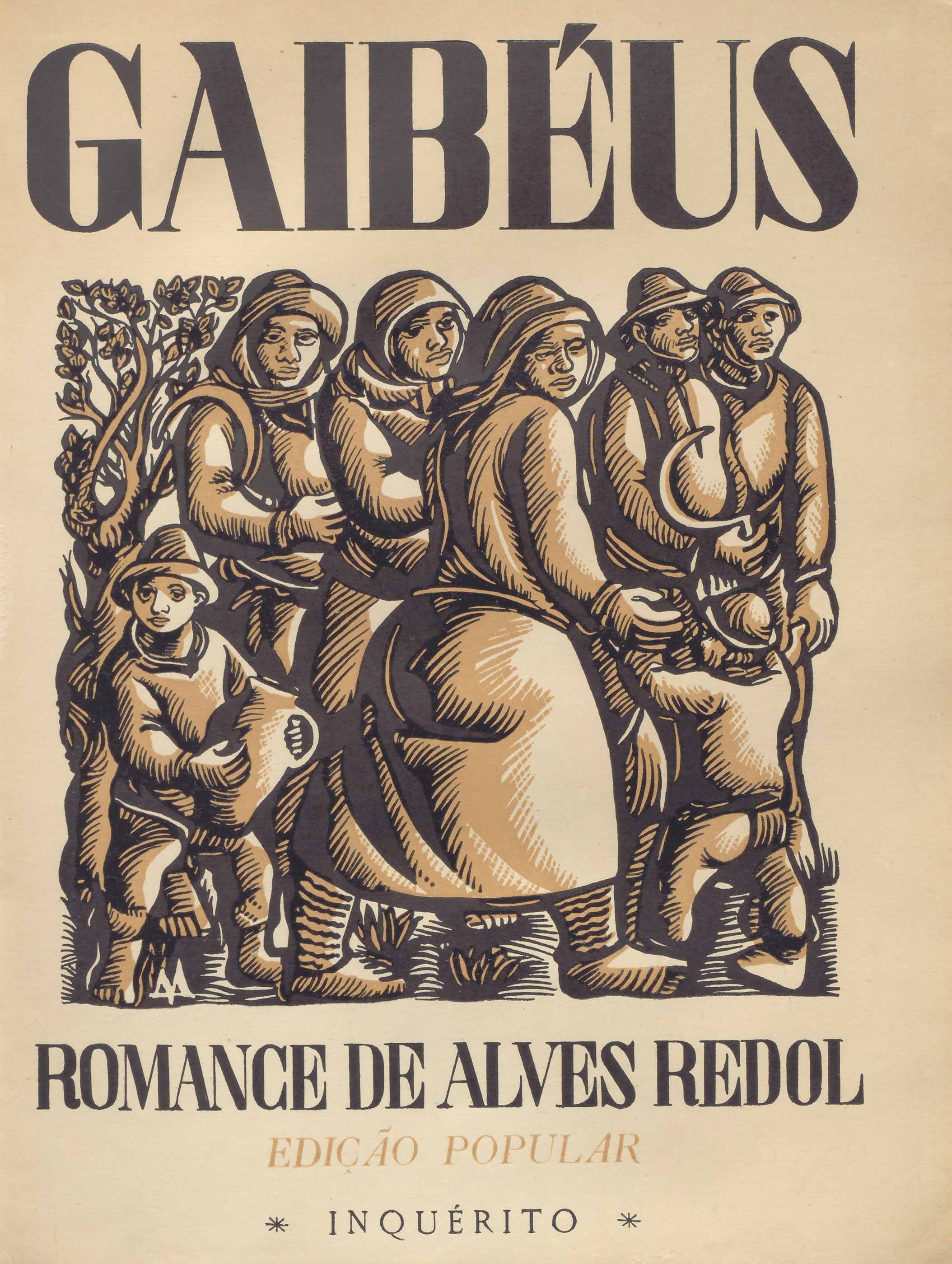

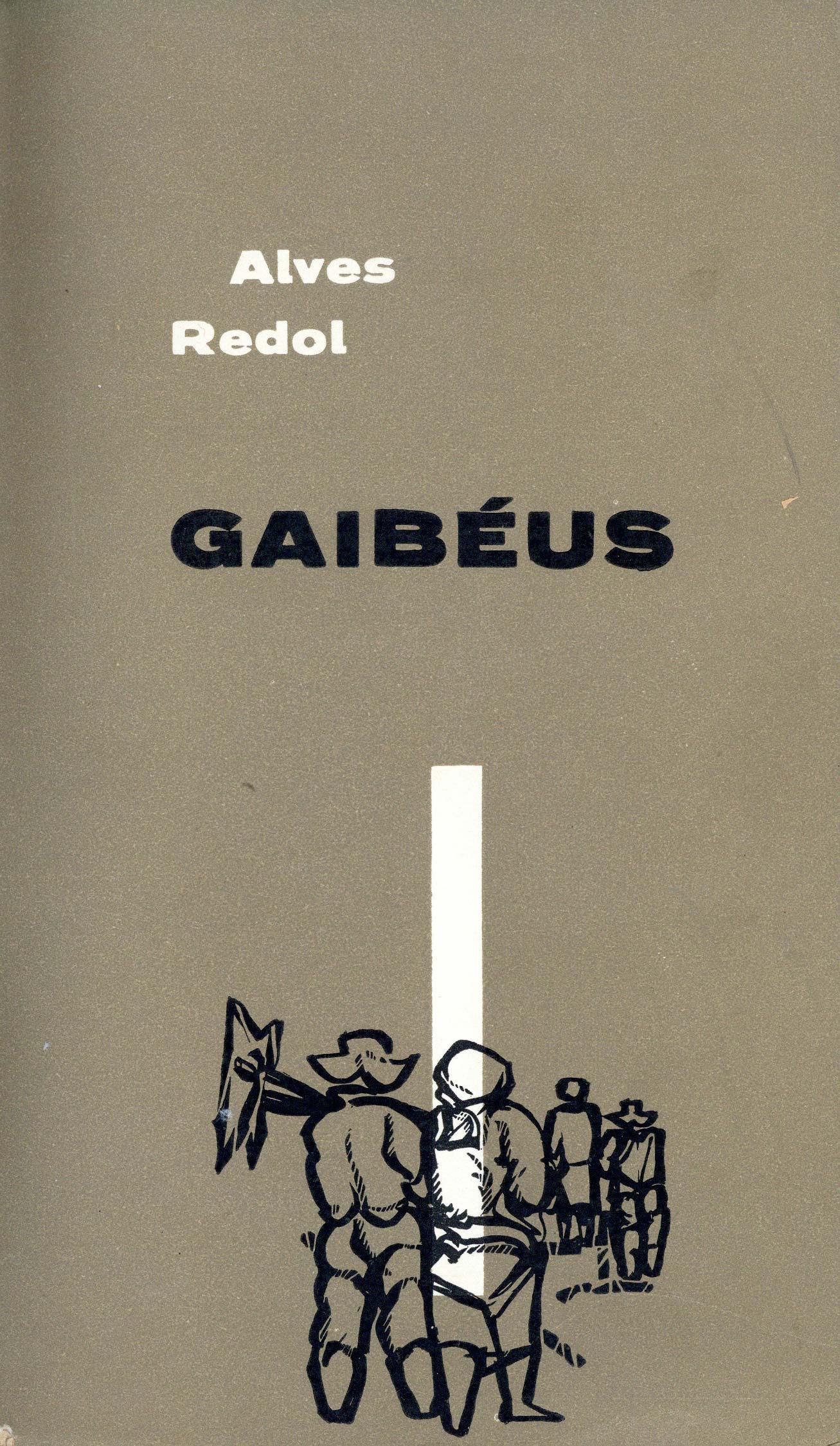

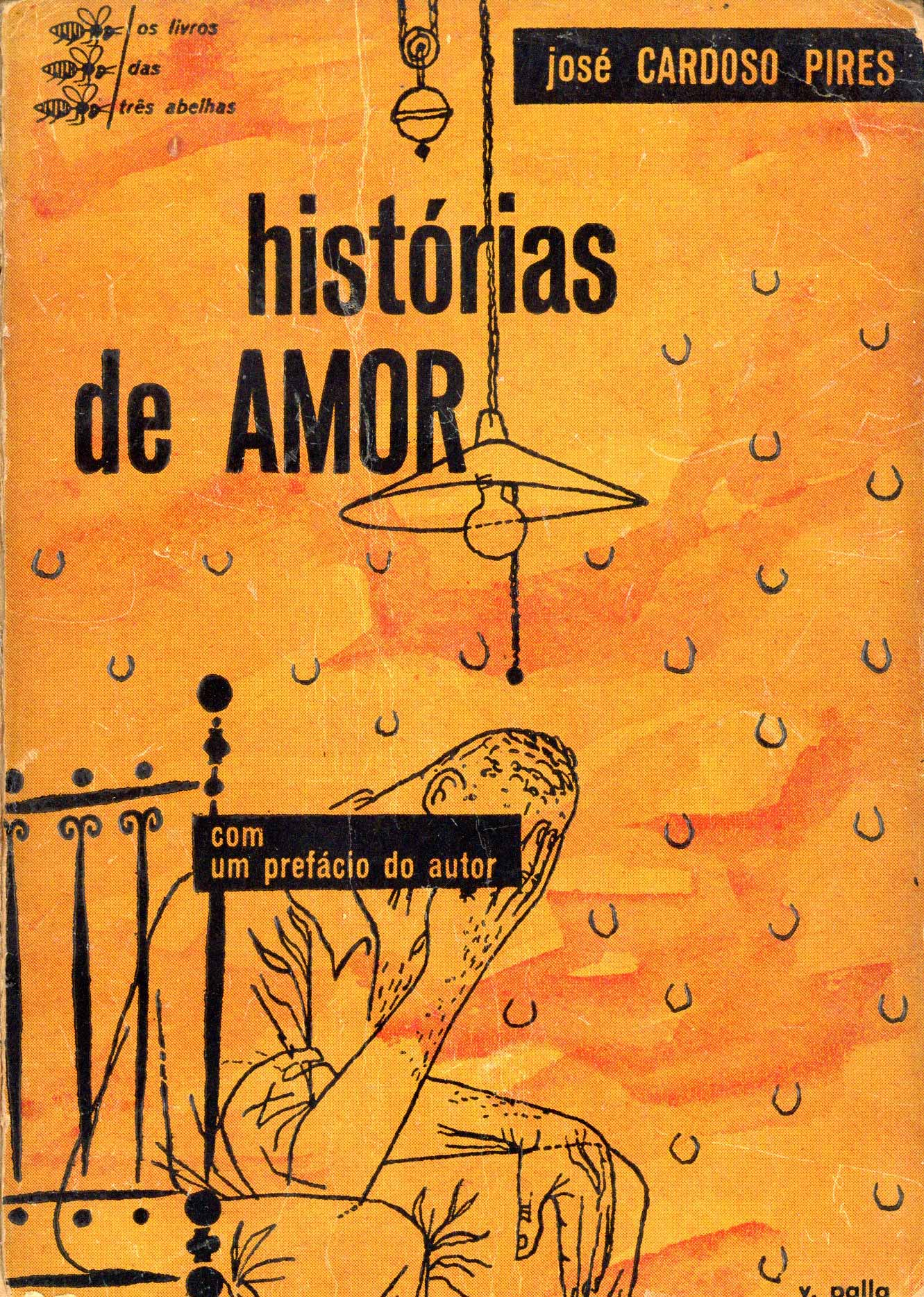

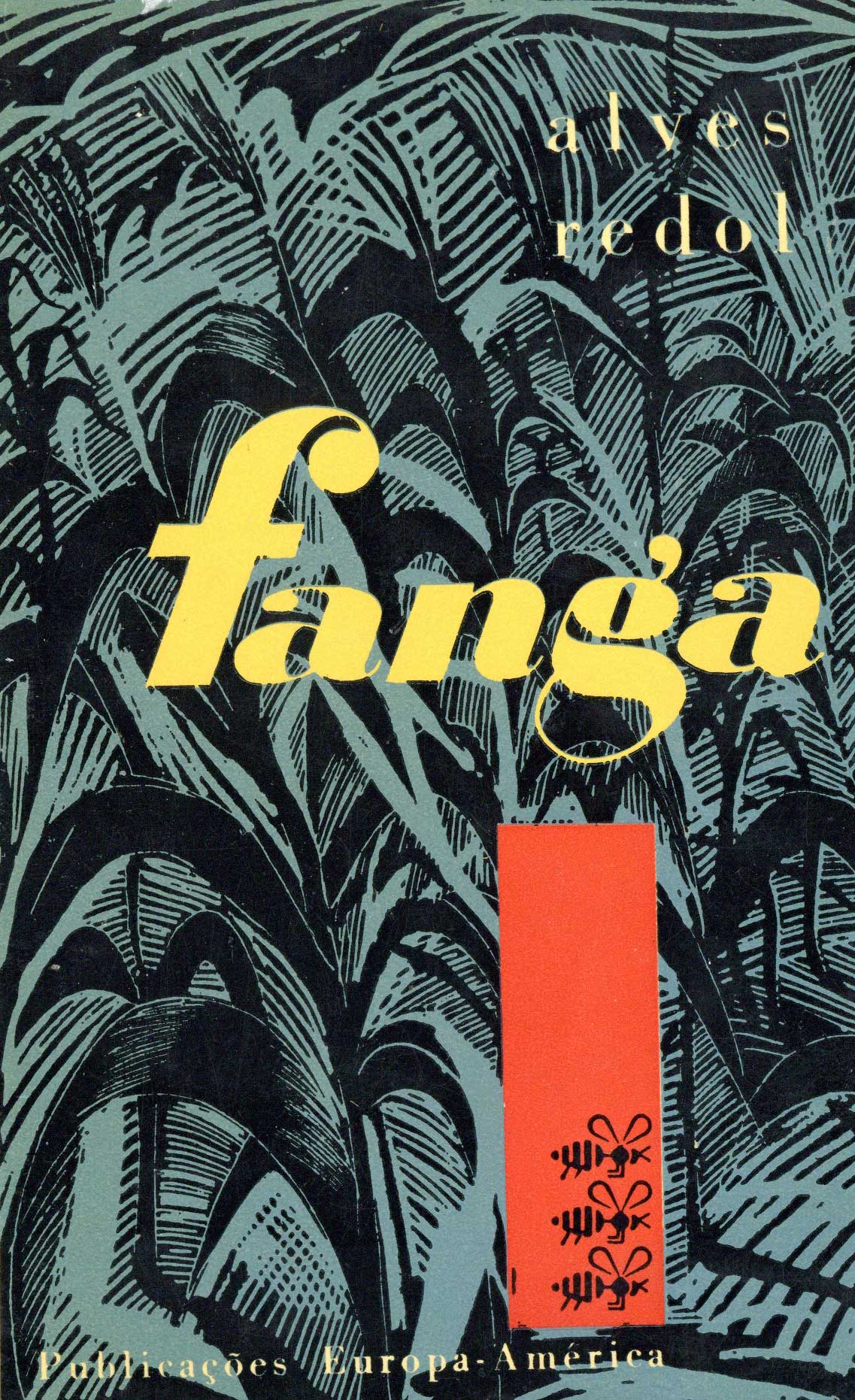

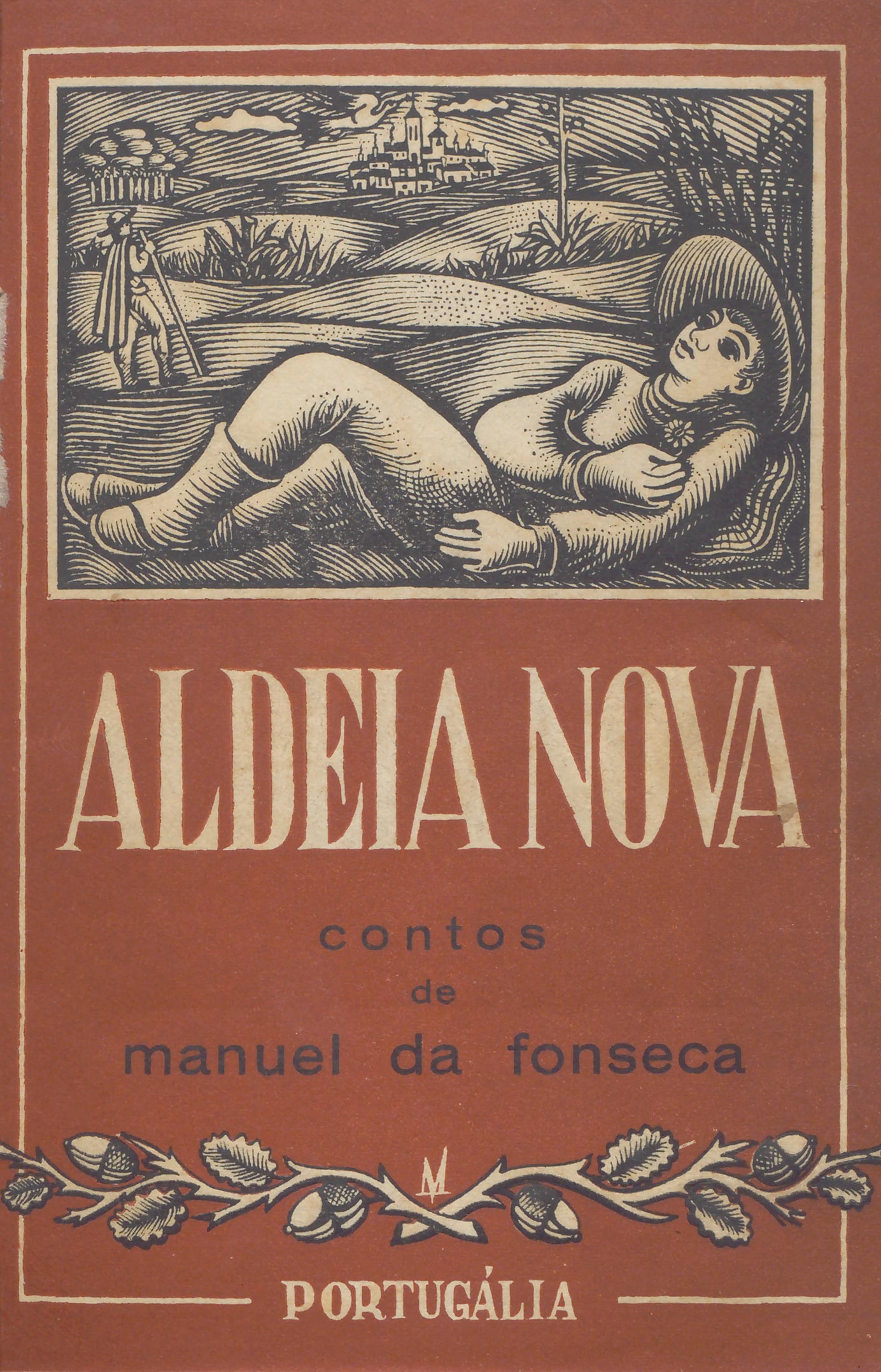

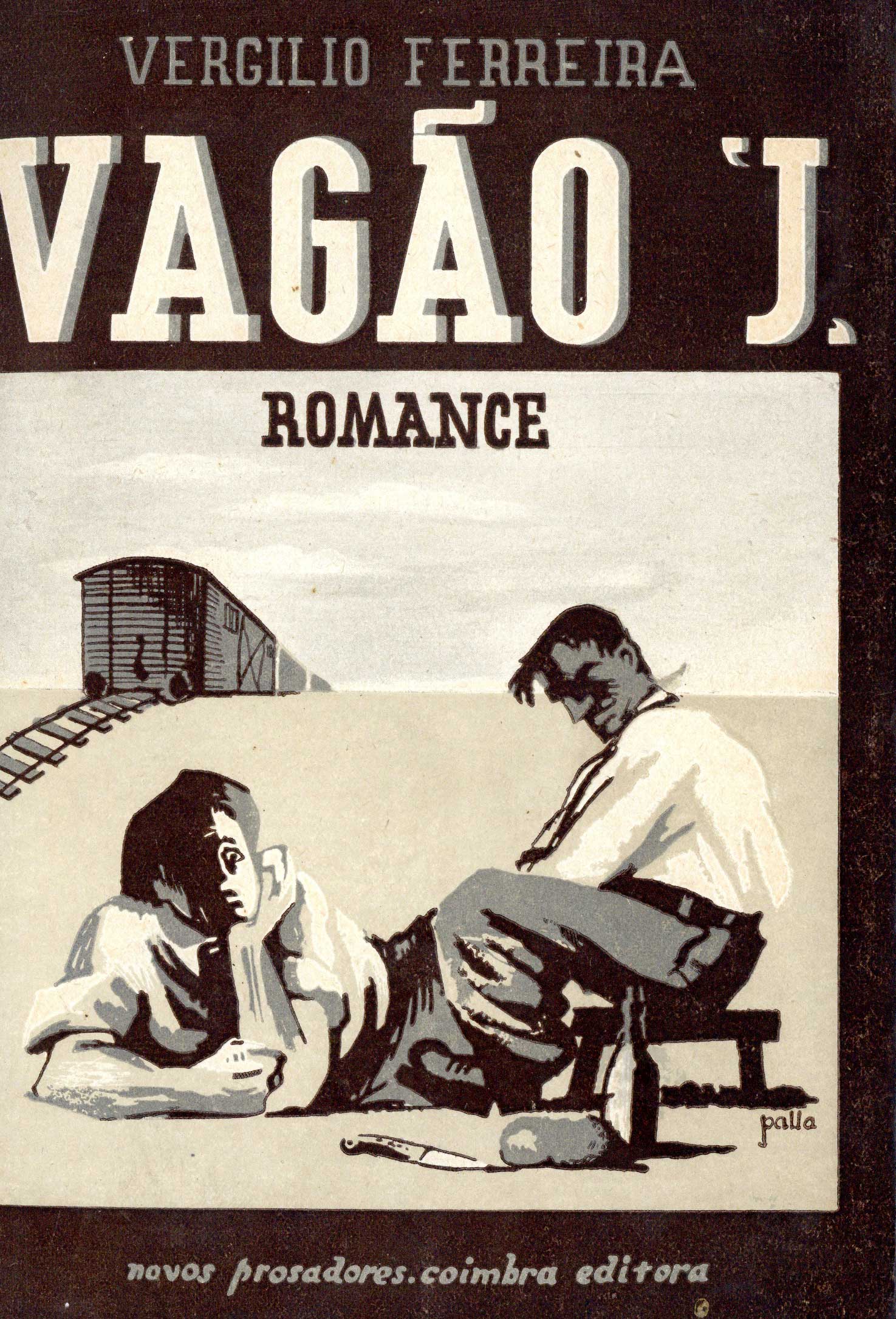

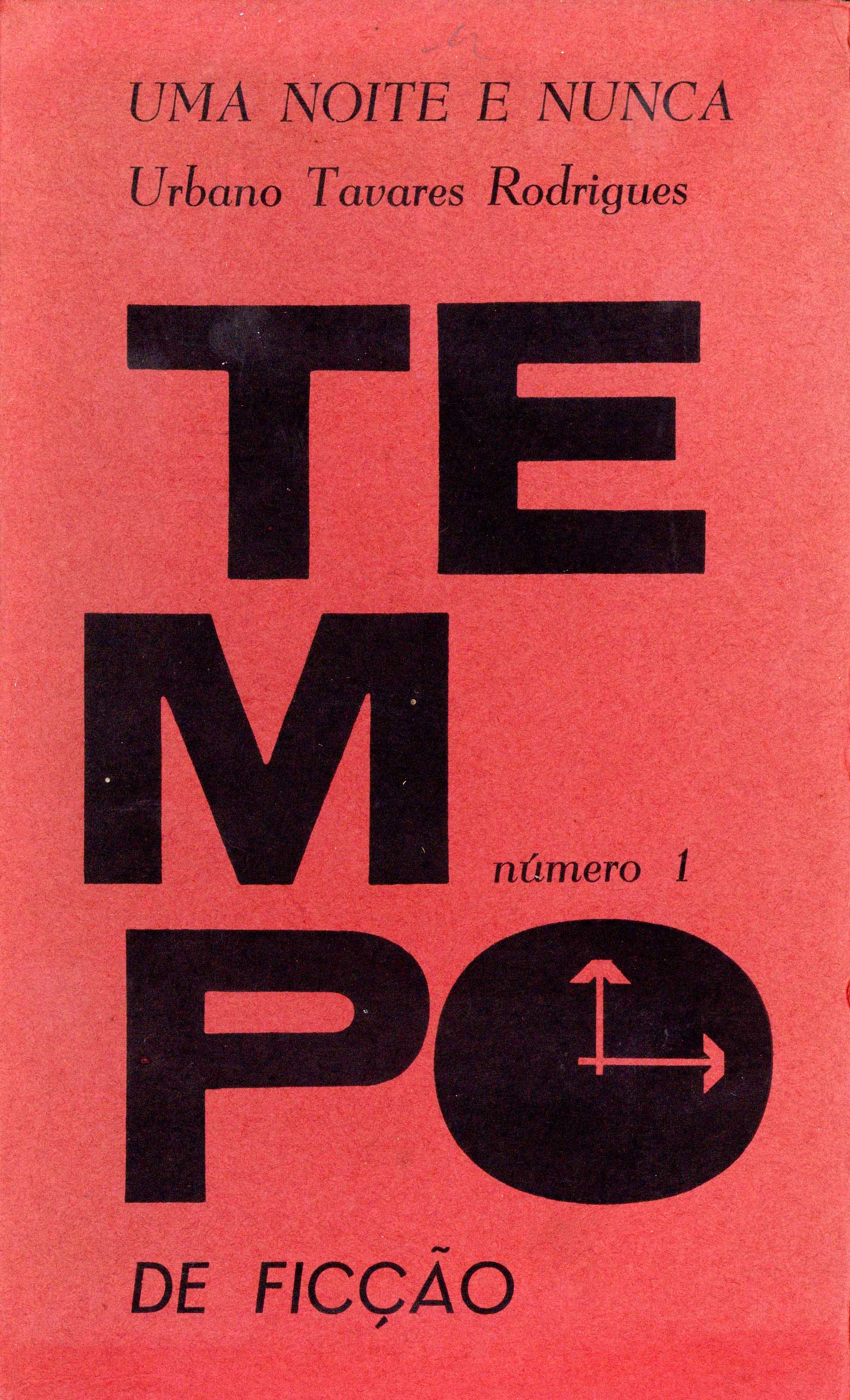

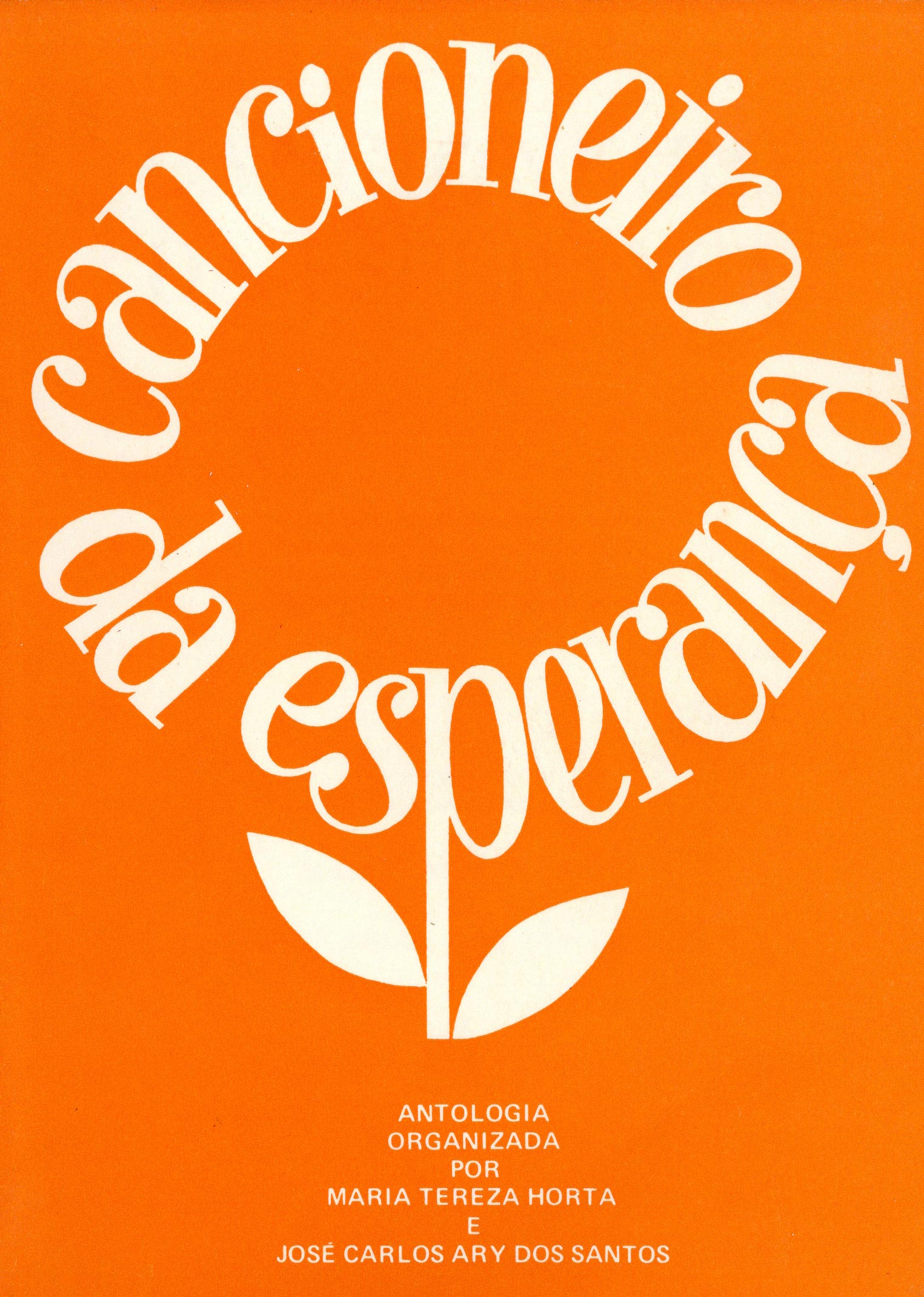

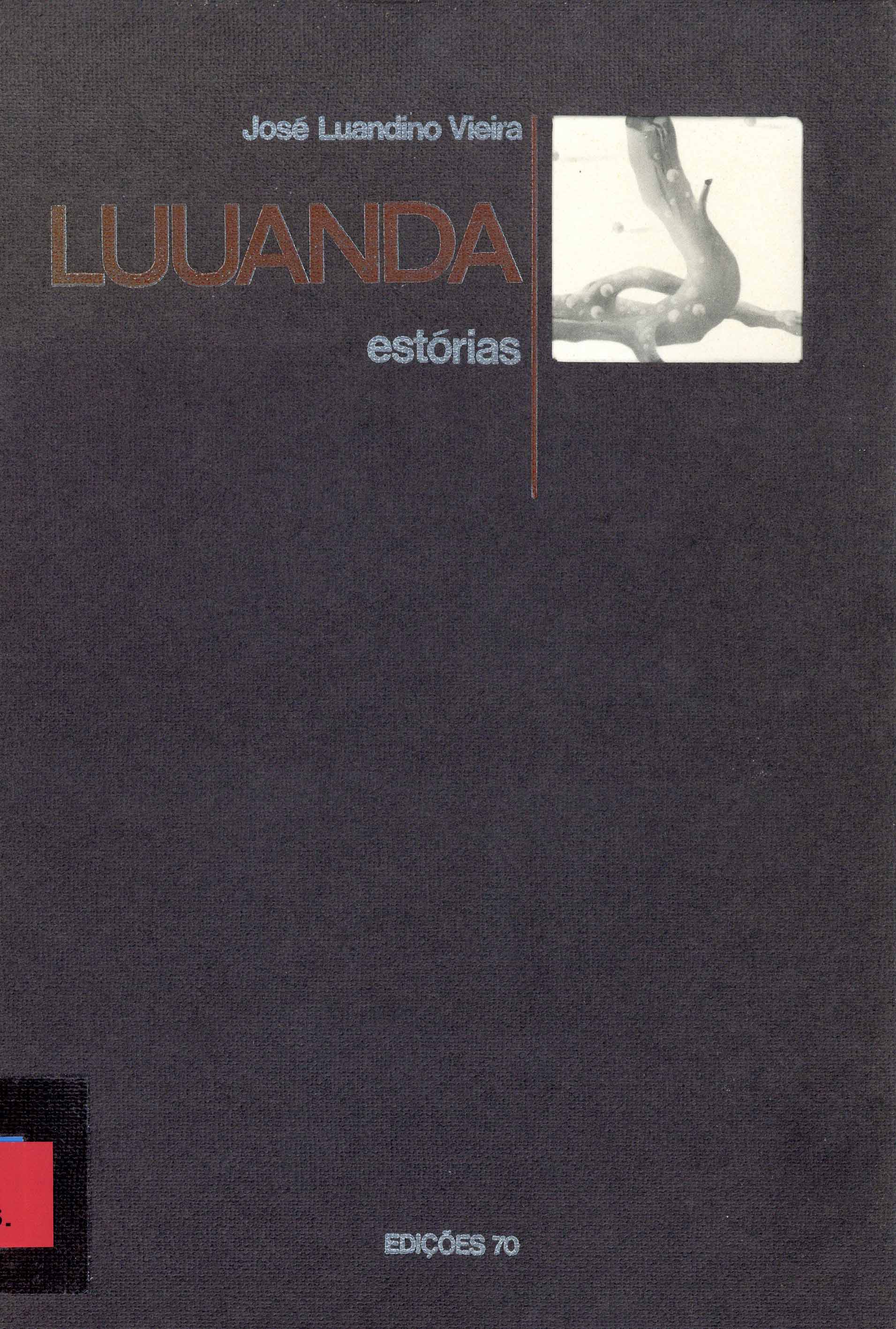

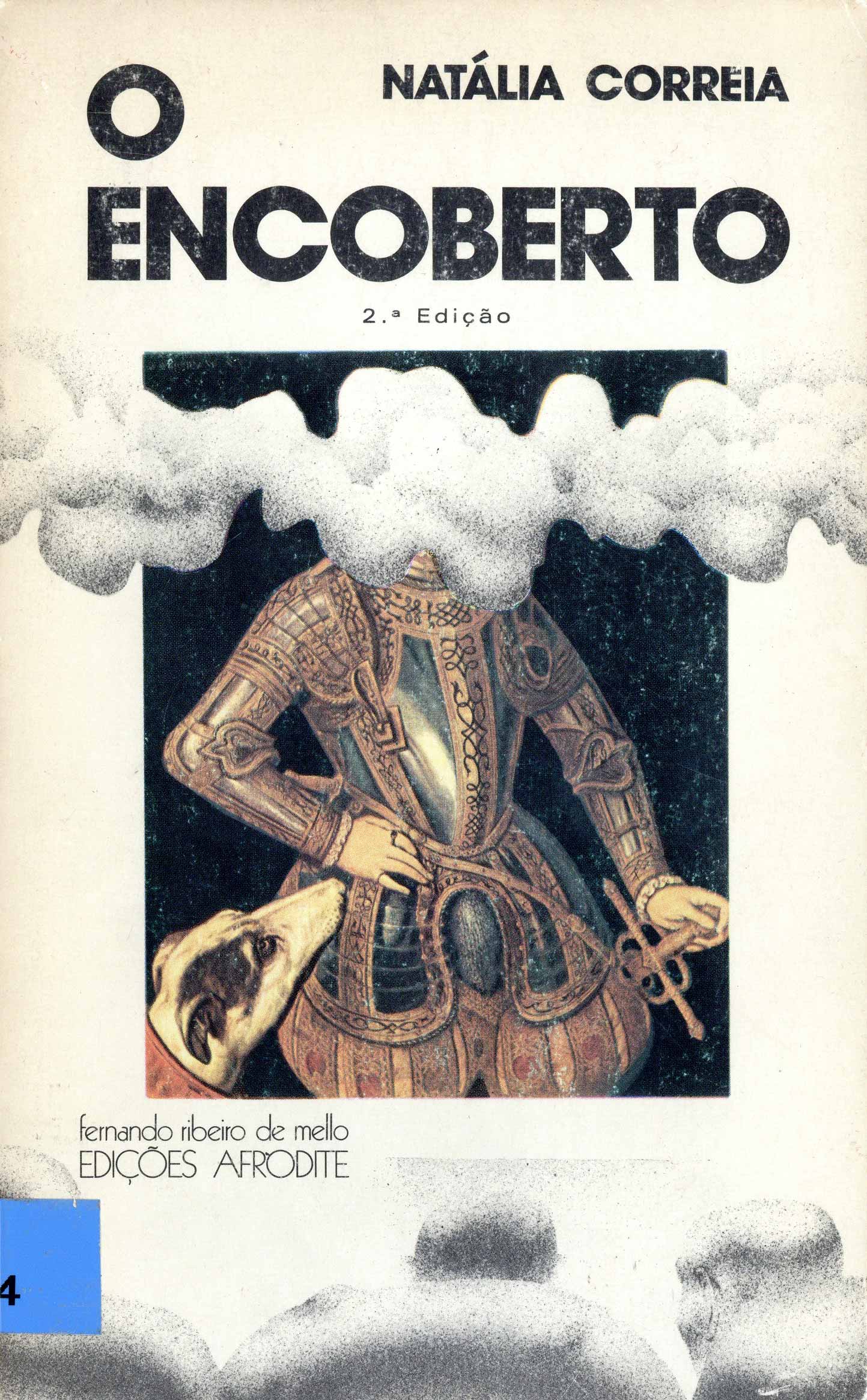

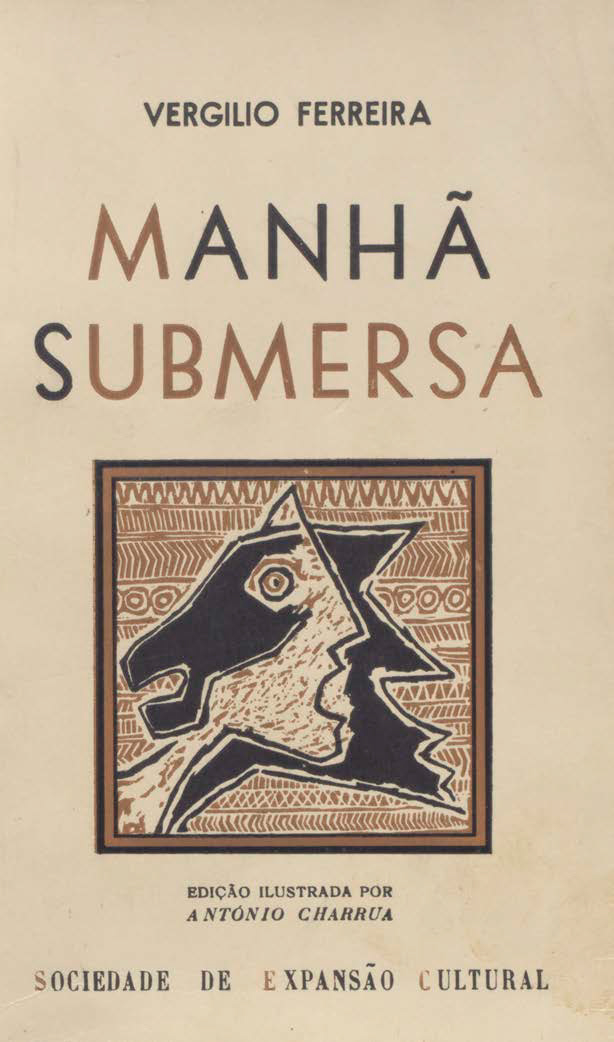

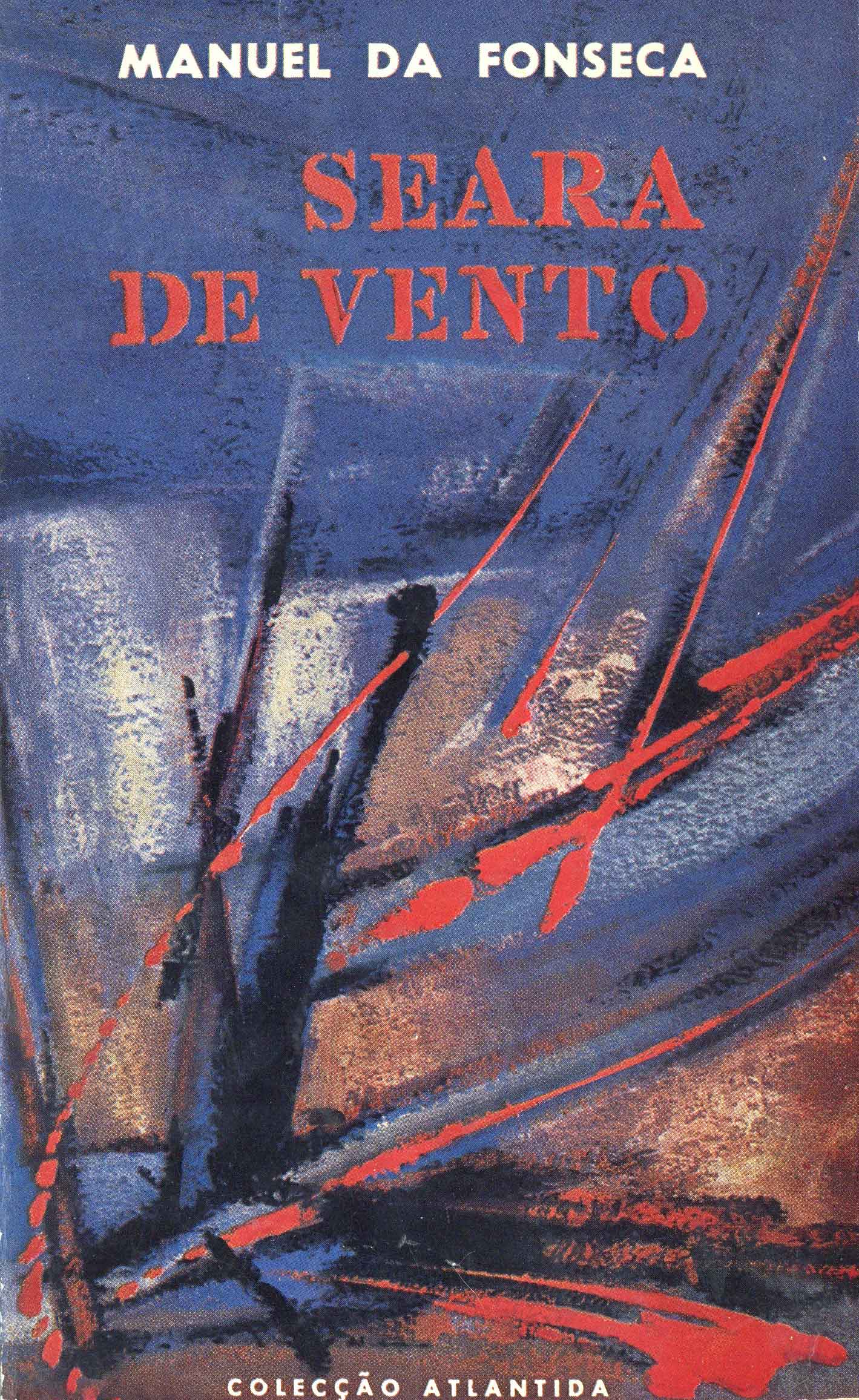

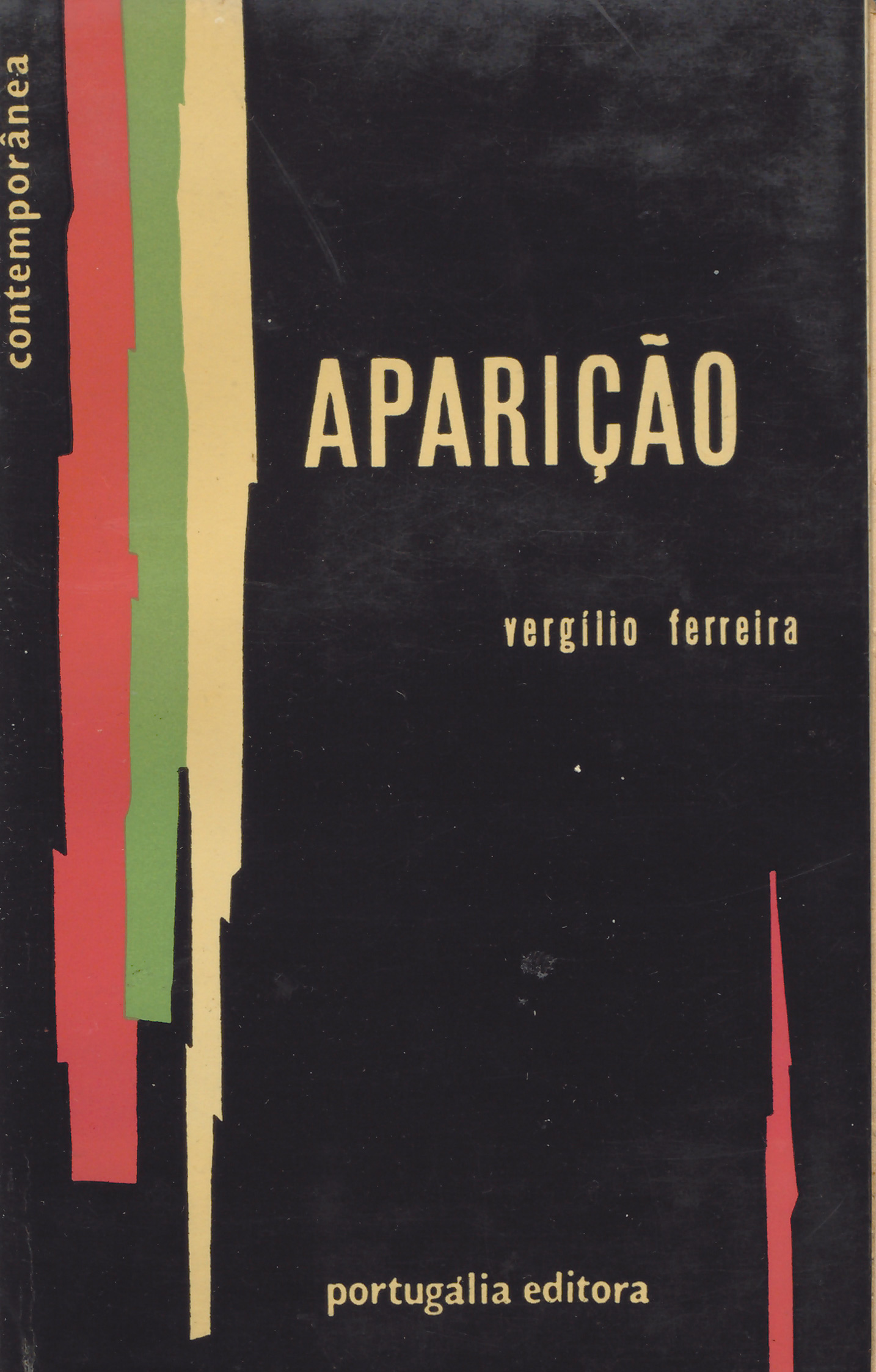

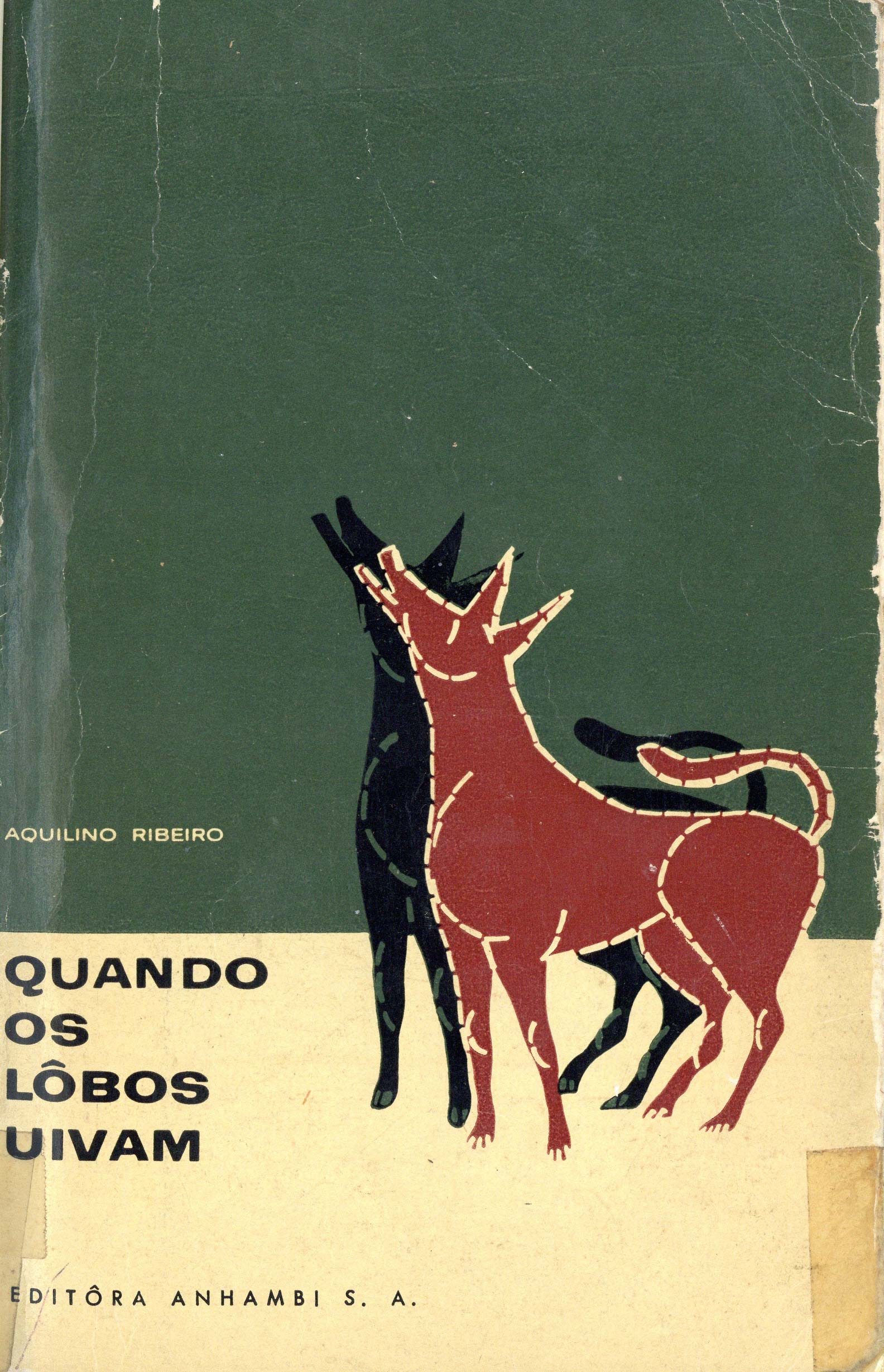

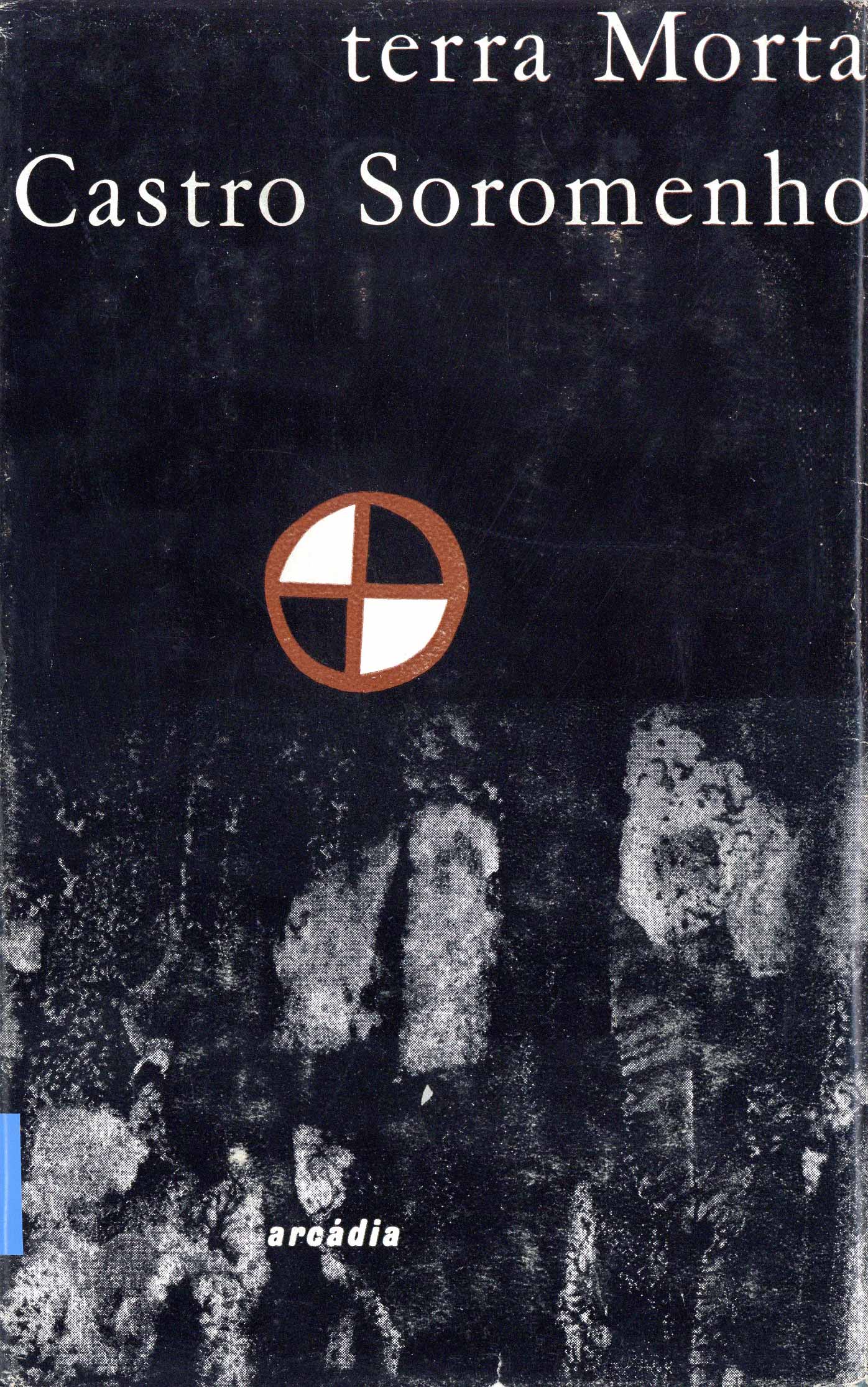

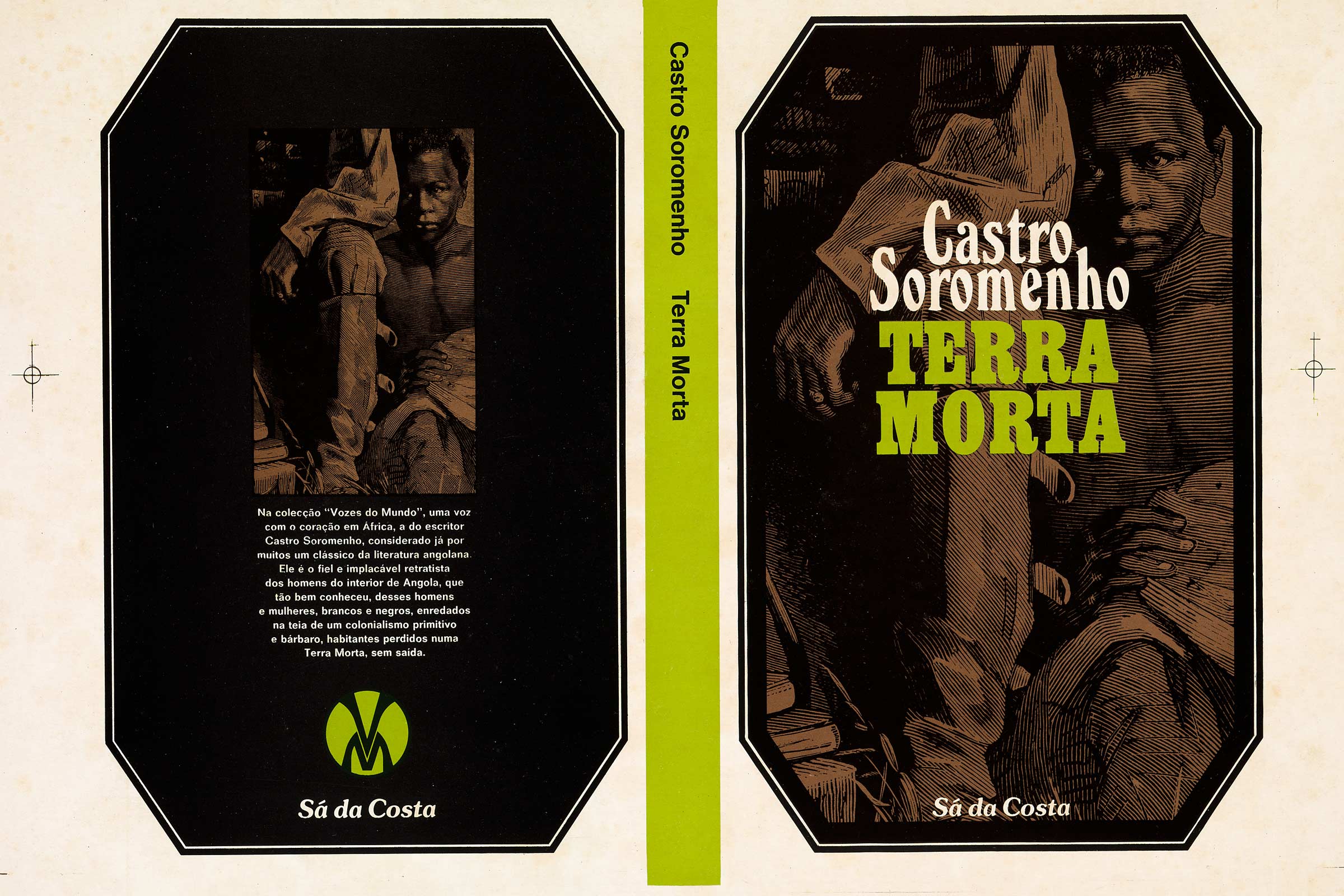

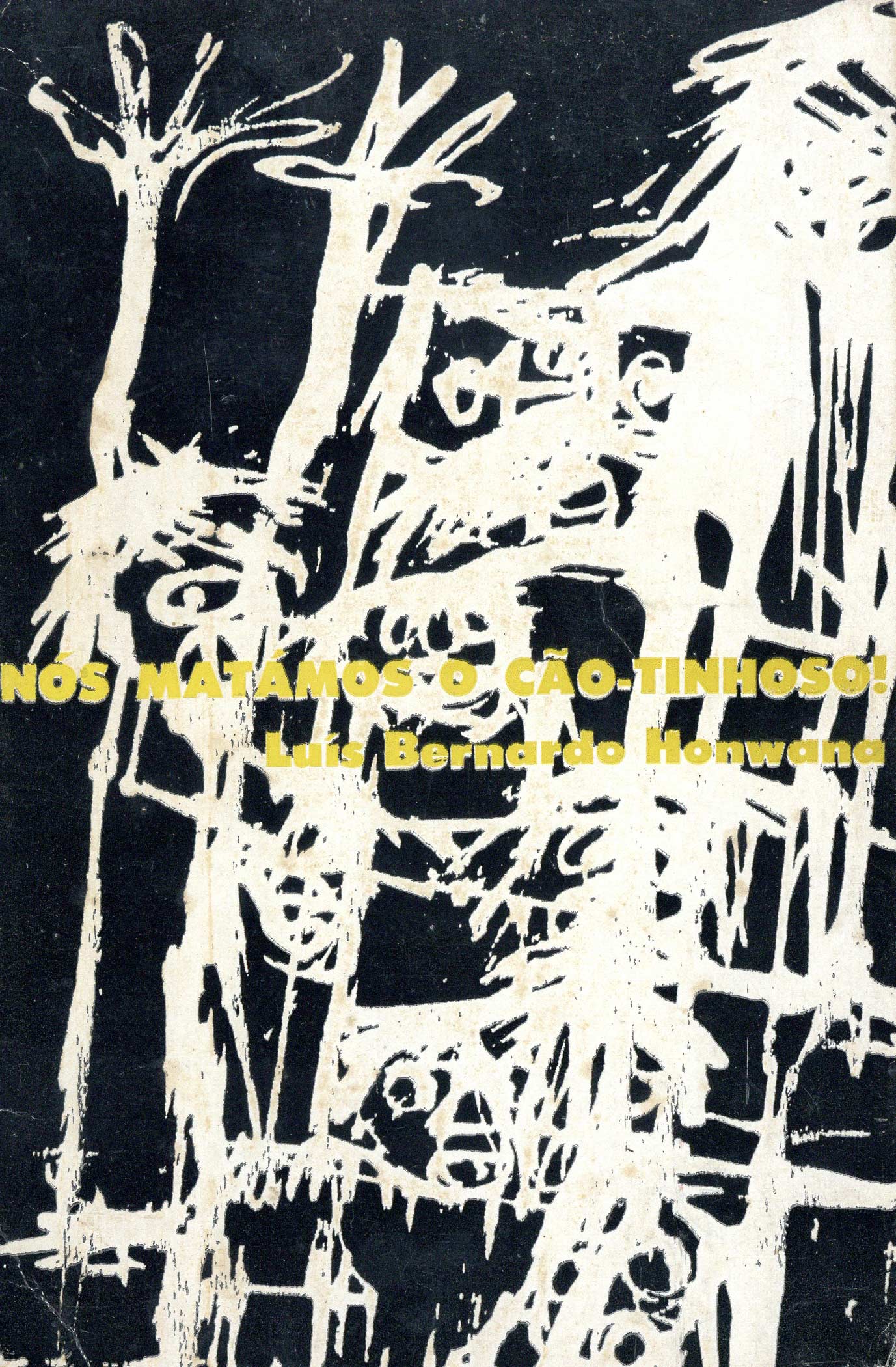

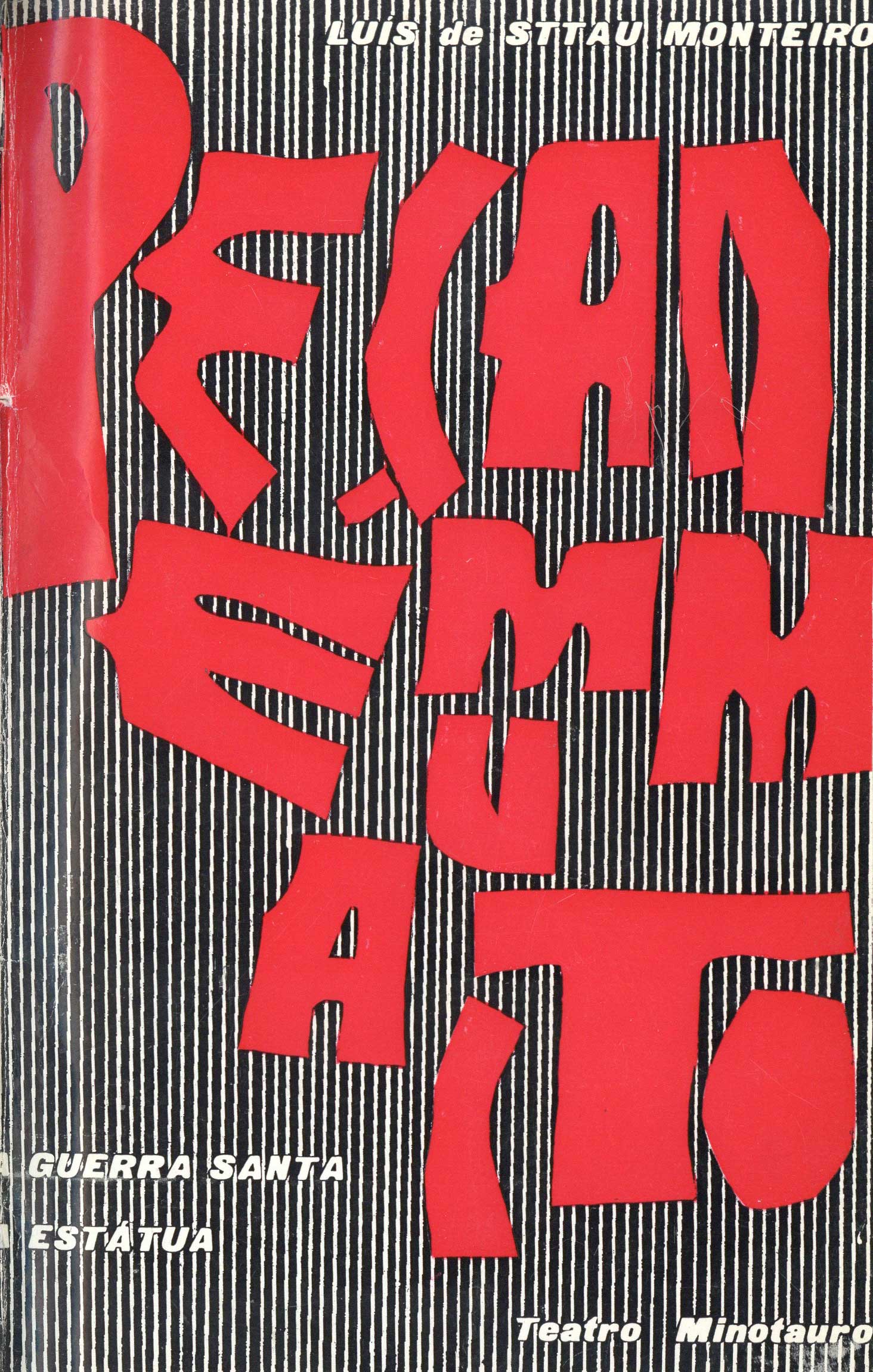

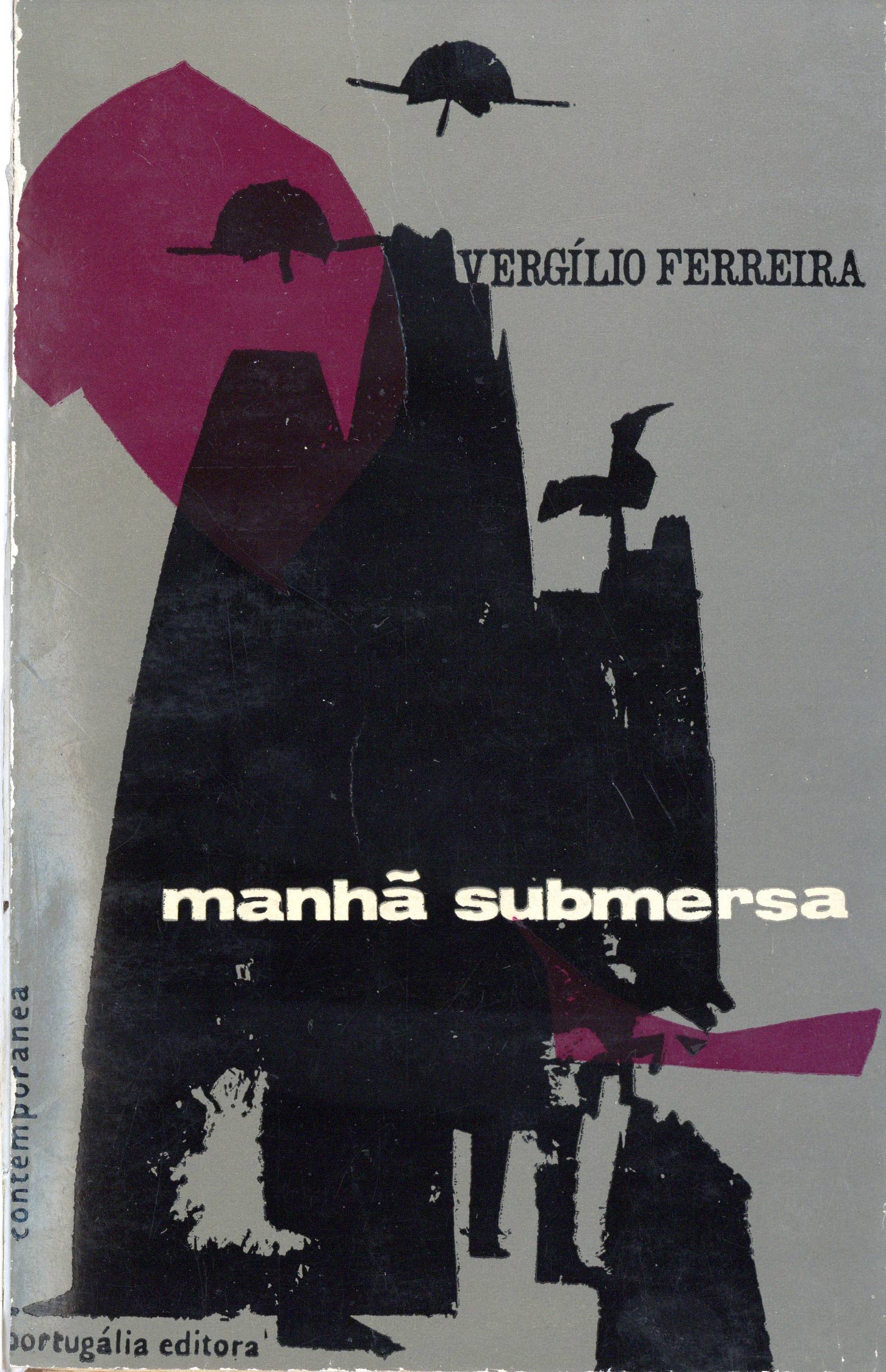

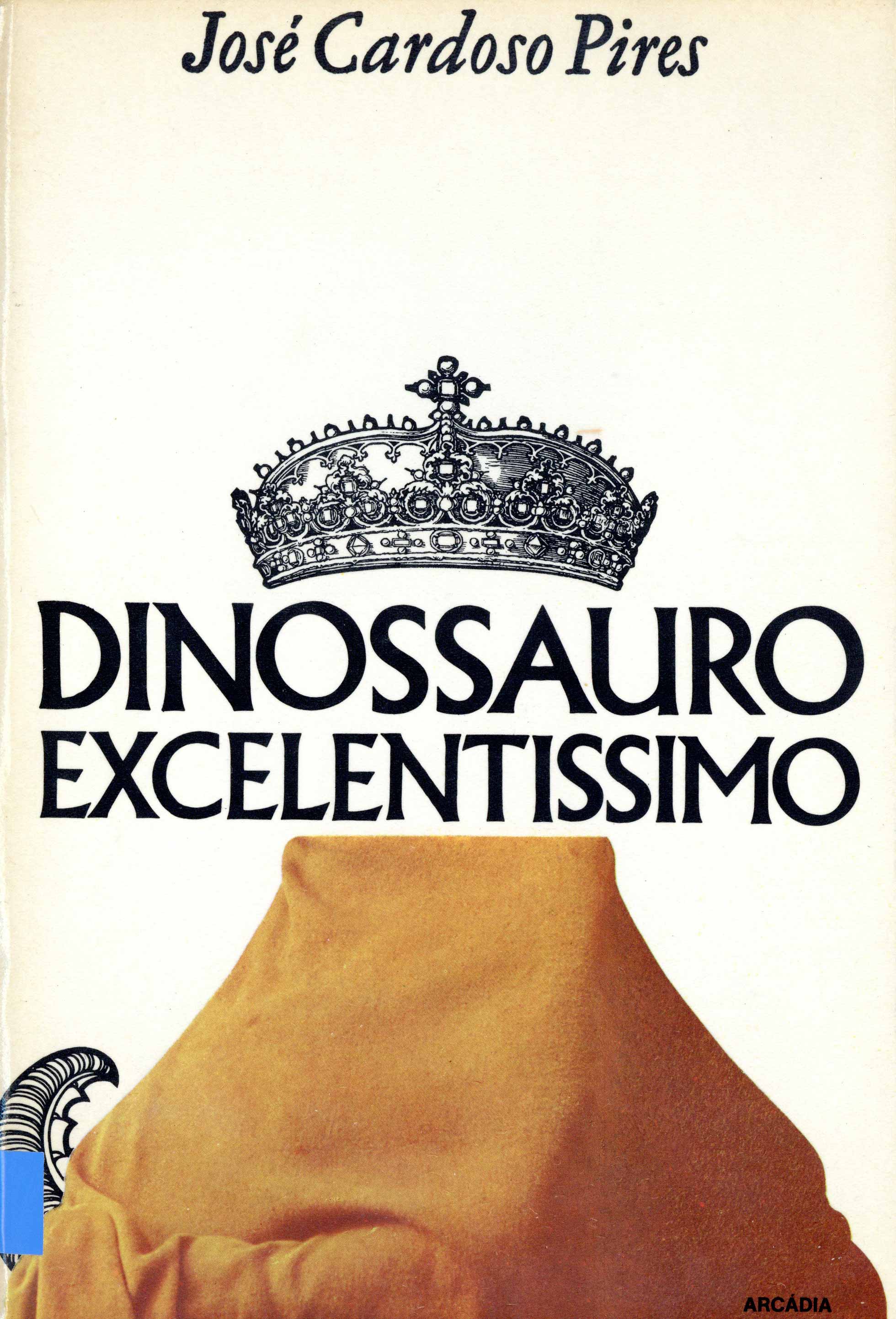

Among the long list of authors whose works were censored and banned by the Estado Novo are some of the biggest names in 20th century Portuguese-language literature: Alexandre O’Neill, Alves Redol, Aquilino Ribeiro, Artur Portela Filho, Castro Soromenho, Jorge Amado, José Cardoso Pires, Luandino Vieira, Luís Bernardo Honwana, Luís de Sttau Monteiro, Maria Isabel Barreno, Maria Lamas, Maria Teresa Horta, Maria Velho da Costa, Mário Cesariny, Miguel Torga, Natália Correia, Orlando da Costa, Vergílio Ferreira.

A survey of this universe reveals that a significant number of the editions had the collaboration of artists to whom the publishers — Ulisseia, Inquérito, Europa-América, Estúdios Cor, Minotauro, Atlântida, Afrodite, Arcádia, Portugália — were given graphic responsibility for the covers and illustrations: António Charrua, Bertina Lopes, Cruzeiro Seixas, Fernando Lemos, João Abel Manta, João Vieira, Júlio Pomar, Manuel Ribeiro de Pavia, Nikias Skapinakis, Sebastião Rodrigues, Vespeira, Victor Palla, for example.

Writers and artists were often companions in various meetings, together in complicity against the oppressive regime that restricted their creativity.

In the case of artists, there were many who expatriated because it wasn’t possible for them to make a living from their art in Portugal, because indifference prevailed here and, even more intolerable, the public’s lack of understanding of their work. For many, the chance to seek out the freedom that the country only regained on 25 April 1974 came through the scholarships that the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation started awarding to young artists as soon as it was founded in 1956.

The books on display belong to the Bordalo Botto Collection, which includes books, newspapers and magazines and some manuscripts by 20th century Portuguese authors. Gathered during his lifetime by Álvaro Bordalo Botto (1909-1986), a bibliophile from Porto, this collection is fundamental to the study of graphic design and literary illustration in Portugal and was donated to the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in 1986 by Álvaro Bordalo himself.

Works from the Library

A selection of books and magazines, photographs, exhibition catalogues and other documents whose themes relate to the history of art, modern and contemporary visual arts, Portuguese architecture, photography and design.