51 Avenue d’Iéna, March 1949

In March 1949, Calouste Gulbenkian reached the age of 80. He was living in Lisbon, where he had arrived from Vichy some seven years earlier. His house in Paris, at 51 Avenue d’Iéna, remained the family home. Apart from his son Nubar, who was living in London, the rest of the family was in residence: his wife, Nevarte Gulbenkian then aged 74, his daughter Rita Essayan (Mme. KLE) and son-in-law, aged 48 and 51 respectively.

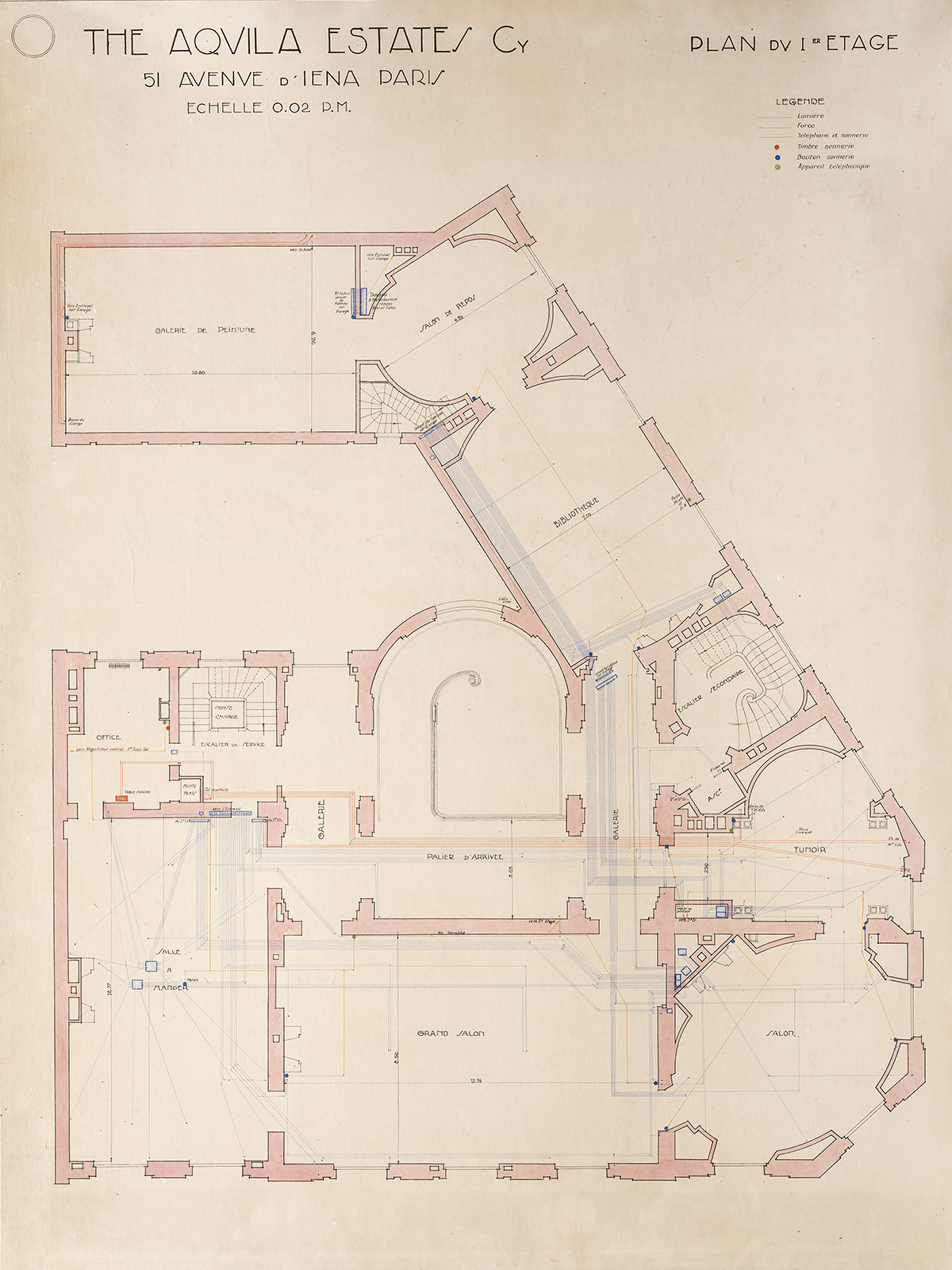

As well as the family, the hotel particulier of course housed Calouste Gulbenkian’s art collection, except for some of the paintings, which had been on loan to the National Gallery, in London, since the 1930s, and the collection of Egyptian art, which since the previous year had been at the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, having previously been displayed at the British Museum.

An office had also been installed, to complement that in London, and handled all matters relating to Calouste Gulbenkian’s business affairs and diplomatic activities, his philanthropic endeavours, art collection and property holdings, as well as his domestic, family and personal affairs.

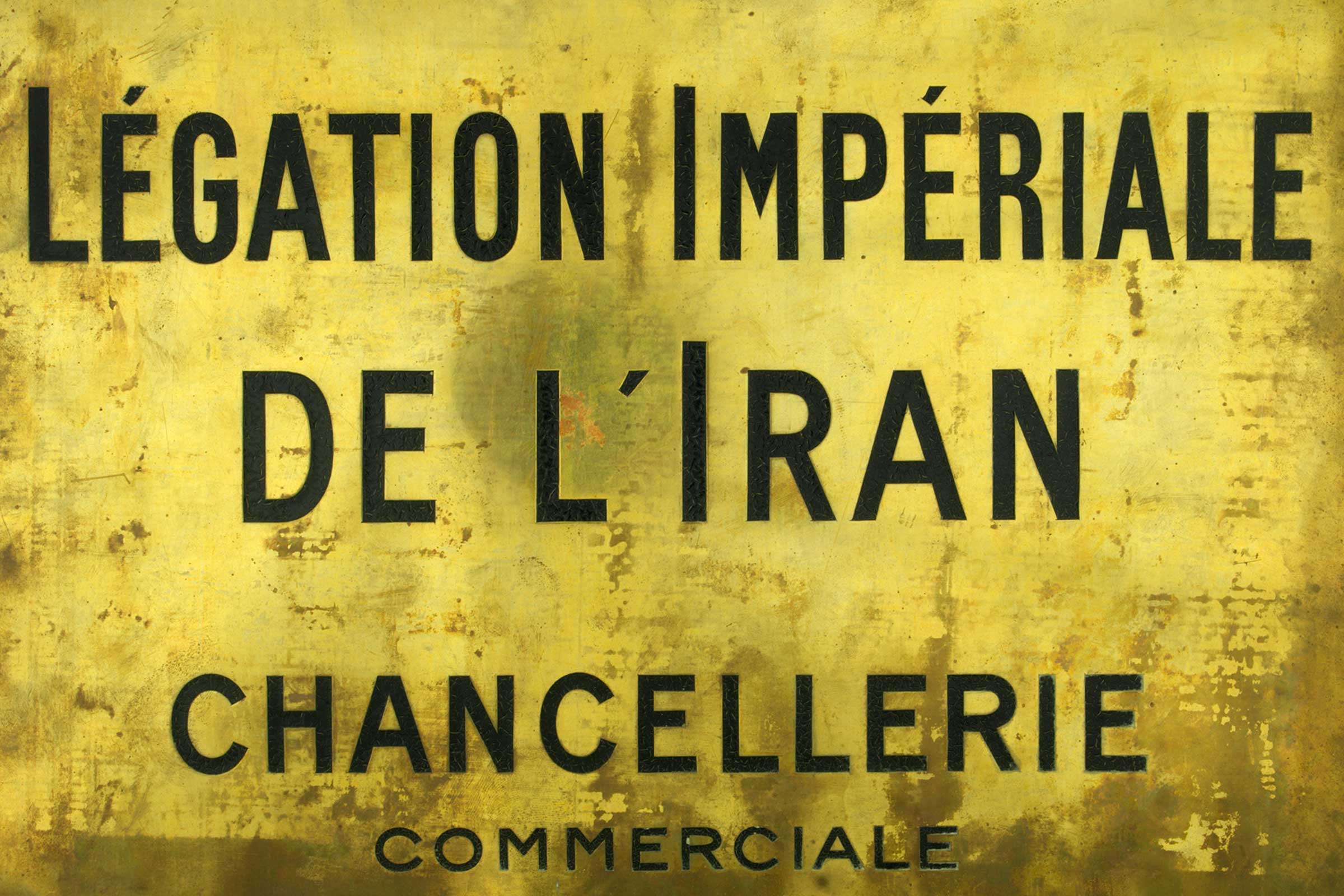

In addition, since the early 1940s, the house at 51 Avenue d’Iéna had been formally recognised as the Commercial Chancellery of the Persian Imperial Legation in Paris, a status secured by Kevork Essayan with the help of the Swiss Embassy, to avoid the property being occupied by the Germans, and in particular by Herman Goering.

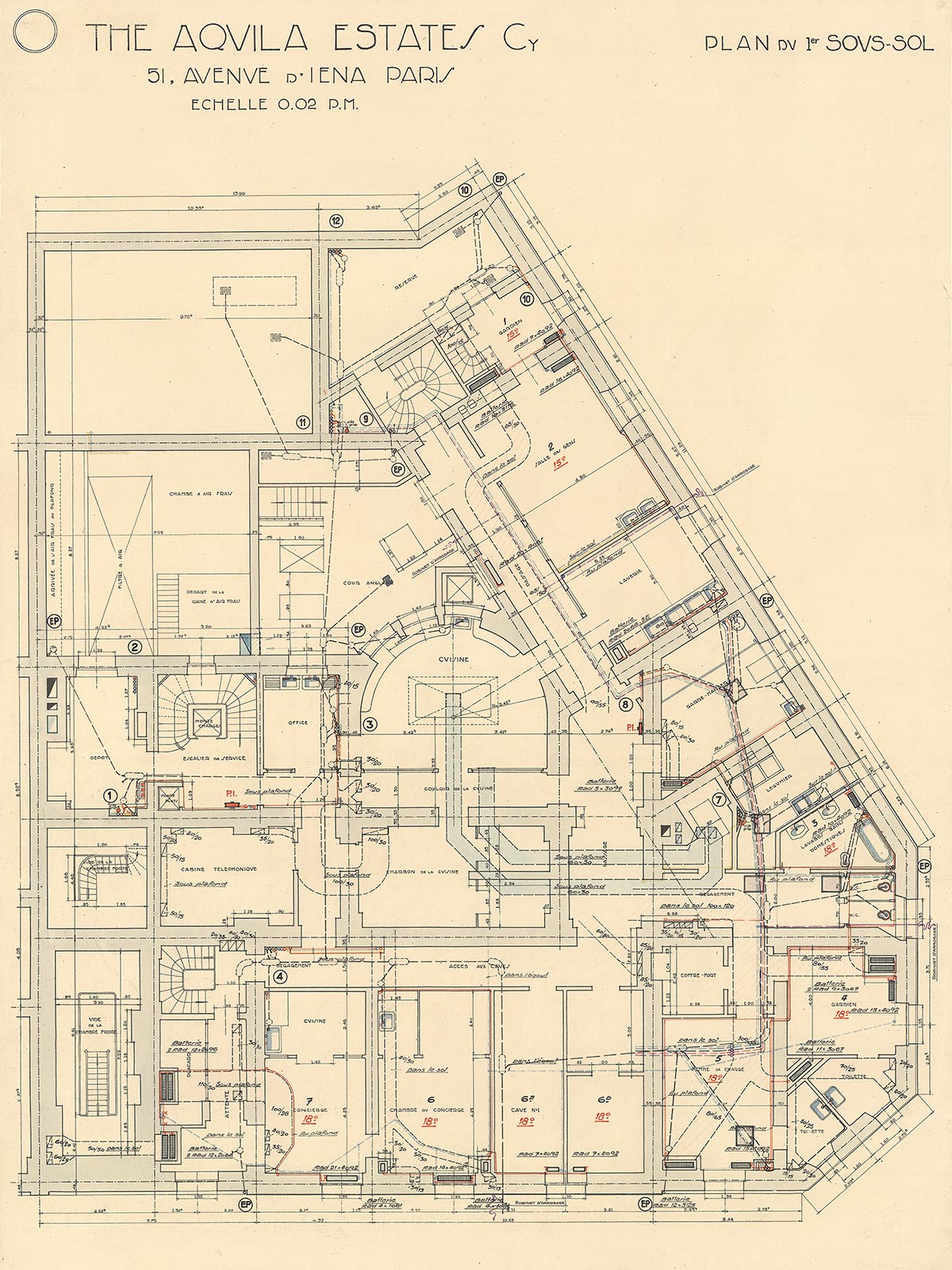

In March 1949, 21 employees (gens de maison) were in service at the house in varying roles: 1 housekeeper, 1 butler (maître d’hotel), 1 lady companion for Mme Nevarte Gulbenkian, 4 male servants (valet, valets à pied, valet particulier), 3 maids (femmes de chambre), 1 laundry maid (lingére), 2 chauffeurs (chauffeur de maître and chauffeur), 2 cooks-chef (cuisinier and cuisinier) and 2 assistant cooks (garçon de cuisine, fille de cuisine), 2 doormen (concierges), 1 electrician (chef-electricien) and 1 handyman (travaux d’entretien). This team, most of whom lived in, were assisted by temporary external staff whenever necessary.

The office employed 5 secretaries, one of whom, Mme. Theis, was working for Calouste Gulbenkian in Lisbon. The office staff also included Robert Gulbenkian, Calouste Gulbenkian’s nephew (son of Vahan and Françoise Gulbenkian), then aged 25, and his cousin Garbis Selian, manager of Les Enclos, the estate owned by Gulbenkian near Deauville, Normandy.

The lady of the house was of course Nevarte Gulbenkian, to whom all the staff reported. She would be assisted in this task not only by her daughter, Rita Essayan but also by her son-in-law’s sister, Arax Essayan (Mlle. Essayan) and also by her lady companion, Mme. Marie Tsarska-Dourska. The housekeeper, Virginie Keurhadjian, was, at that time, the lynchpin in the management of the house, as well as a key player in liaison and communication between those above and below stairs, and also the office staff.

Despite Nevarte’s authority in the house, the chain of command went back, in the final instance, to Lisbon and the family patriarch. In effect, it was Calouste Gulbenkian who was in charge and decided on matters relating to the organisation and functioning of the house: working hours, workplaces and meals, the duties of employees, their wages and bonuses, purchasing procedures (suppliers, goods purchased, payments and storage), use and consumption of goods, especially foodstuffs and fuel, as well as safety issues.

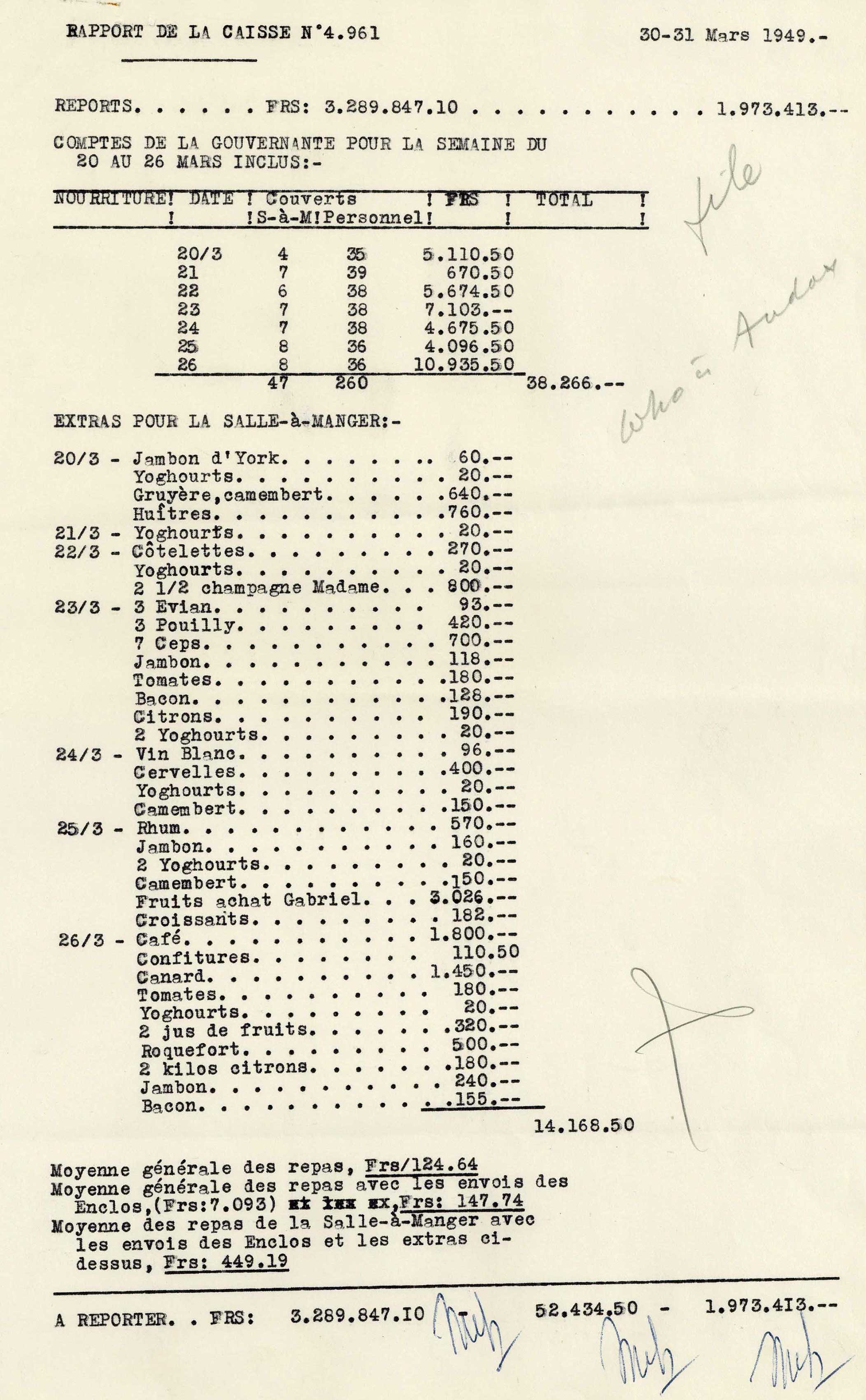

Ledger nr. 4,961, dated 30-31 March 1949 provides evidence that quality information was reported weekly, in a structured and detailed form, under the professional supervision of the office.

It is interesting to note that, from a bookkeeping perspective, the house was organised into different accounts, which functioned as cost centres, and where individuals could be held accountable.

The most important and detailed of these accounts were those kept by the housekeeper. These weekly accounts itemised pharmacy expenses, expenses not included in other accounts and, in particular detail, expenditure on food and drink, and consumption, both by the family and by staff.

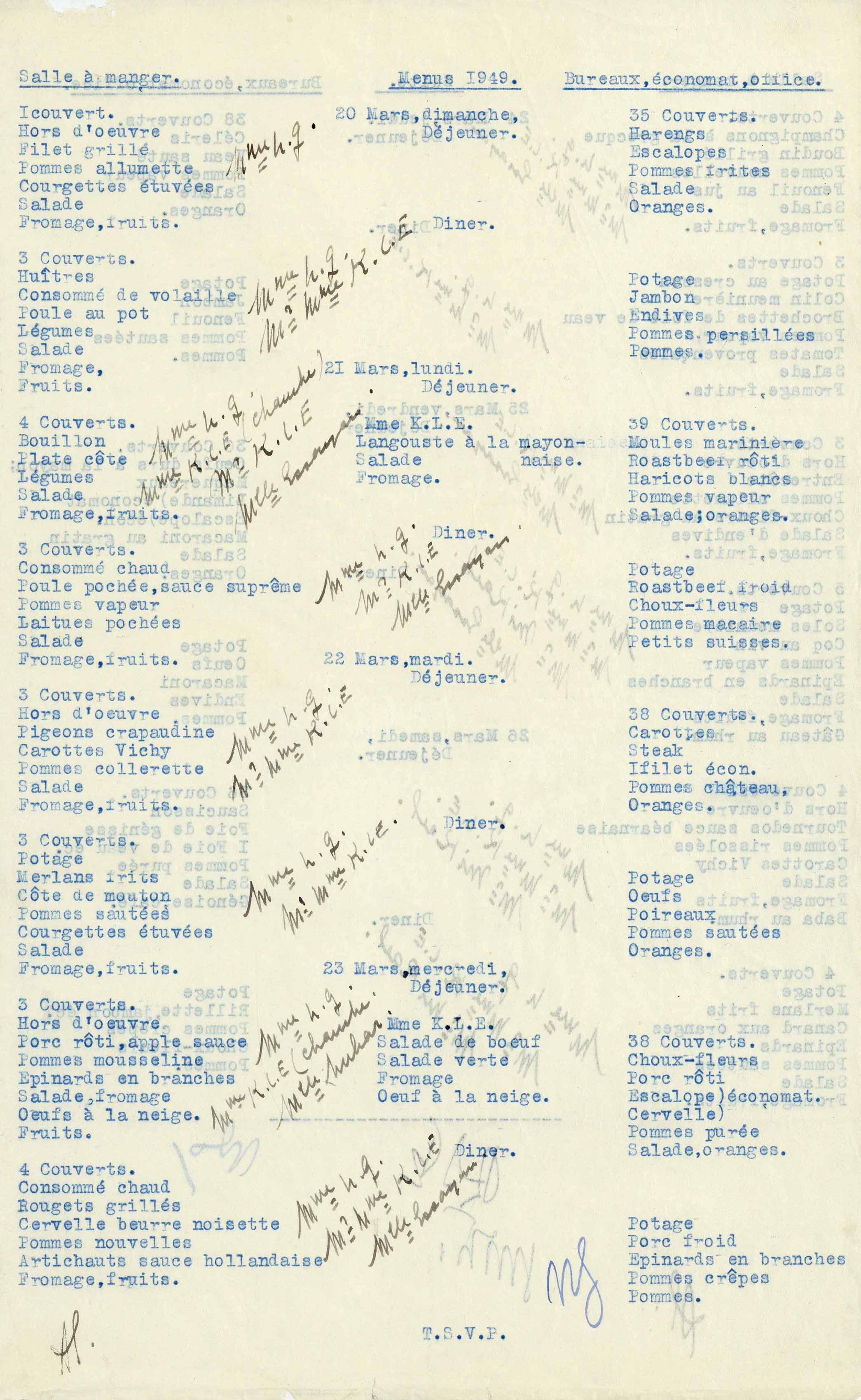

These accounts provide aggregates by item, and also include supporting documents, duly checked and filed, as well as some special indicators, such as the average cost of family and staff meals and, in the case of family meals, who partook of them (including guests), information on any special menus and the place where served, when not in the dining room.

It may be seen that, in the week of 20 to 26 March, the period covered by the housekeeper’s accounts included in the featured ledger, most of the family meals were served to only Mme. Nevarte Gulbenkian, her daughter and son-in-law. This group was sporadically joined by the son-in-law’s sister, Arax Essayan, who worked part-time in the house, and, at weekends, by the young Mikäel. There were no visitors that week, which bears out the idea obtained from other sources that Calouste Gulbenkian was not keen on the house being frequented by outsiders. As regards staff meals (including office staff, who had their own dining room, and the domestic servants, who ate in their own quarters), the average number served per meal was around 19 for the week in question.

In the case of family menus, there was a distinction between “staples” and items of food and drink considered as “extras”, subject to specific control by the housekeeper, and for which separate accounts were kept, where it was normal to indicate which member of the family consumed them.

Just under four years after the Germans surrendered to the Allies, one month after the end of bread rationing in France, and at a time when rationing was still in force for coffee and sugar, it is interesting to note that the following items, among many others, were regarded as “extras” in the housekeeping for Calouste Gulbenkian’s Paris residence: cheese and yoghurt, ham and bacon, fruit and fruit juices, tomatoes and lemons, wine, croissants, coffee, still mineral water.

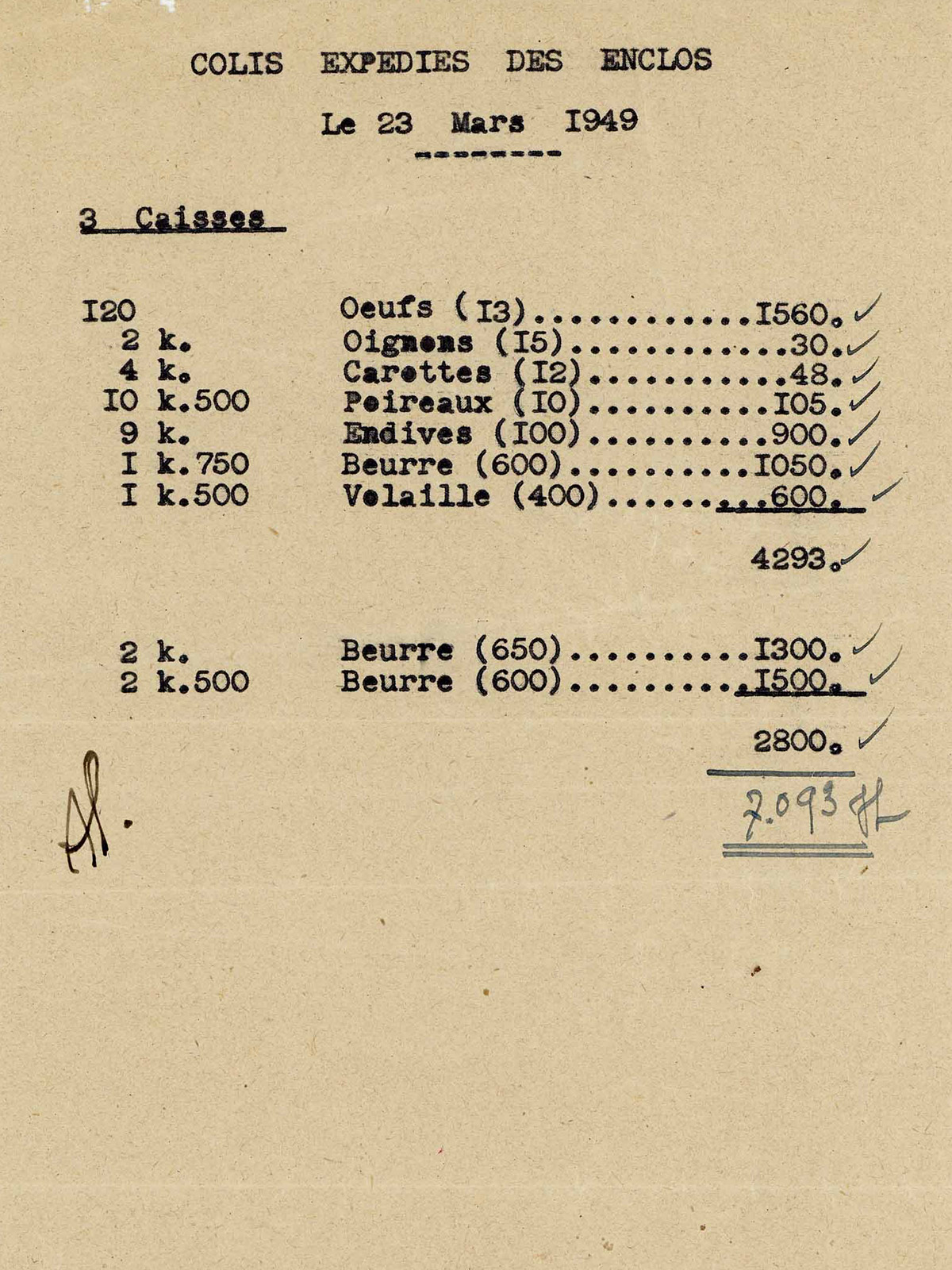

It is also significant that even the produce from Les Enclos, periodically sent to Paris (and, in certain cases, also to Lisbon), was assigned a value in advance, which was then considered when determining the average cost of family and staff meals.

It was part of the housekeeper’s job to monitor price fluctuations in the shops, as well as to check the weight and cost of produce purchased by the cook, when it was delivered to the house. This would then be double checked by two of the women assisting Nevarte in the running of the house.

Another clue that a close grip on kitchen expenses was regarded as an essential part of running the house is found in the fact that the documents attached by the housekeeper to the accounts, in particular the weekly list of menus and the list of produce sent from Les Enclos, were invariably confirmed by all those with ultimate responsibility for household management: Nevarte, Rita e Arax Essayan

The other accounts, rendered monthly, were these:

In addition to payments for goods and services, wages, taxes and contributions, gratuities and donations, organised in the accounts mentioned above, the ledger also mentions allowances to family members (allocations famille), paid in March 1949 to Nevarte Gulbenkian, Rita e Kevork Essayan, Mr e Mme Vahan Essayan, parents of Kevirk, Karnig Gulbenkian, brother of Calouste (and father of Robert Gulbenkian). It also featured expenditure relating to medical and nursing services (consultations, nighttime visits, treatments and medicines) for the resident family members, but also for Kevork’s parents.

As well as enabling us to recreate a picture of everyday domestic life at Calouste’s house in Paris, these documents offer a glimpse of how far he went in overseeing arrangements and of the care he took in ensuring his family’s welfare in the minutest detail.

From the Archives

Significant moments in the history of Calouste Gulbenkian and the Gulbenkian Foundation in Portugal and around the world.