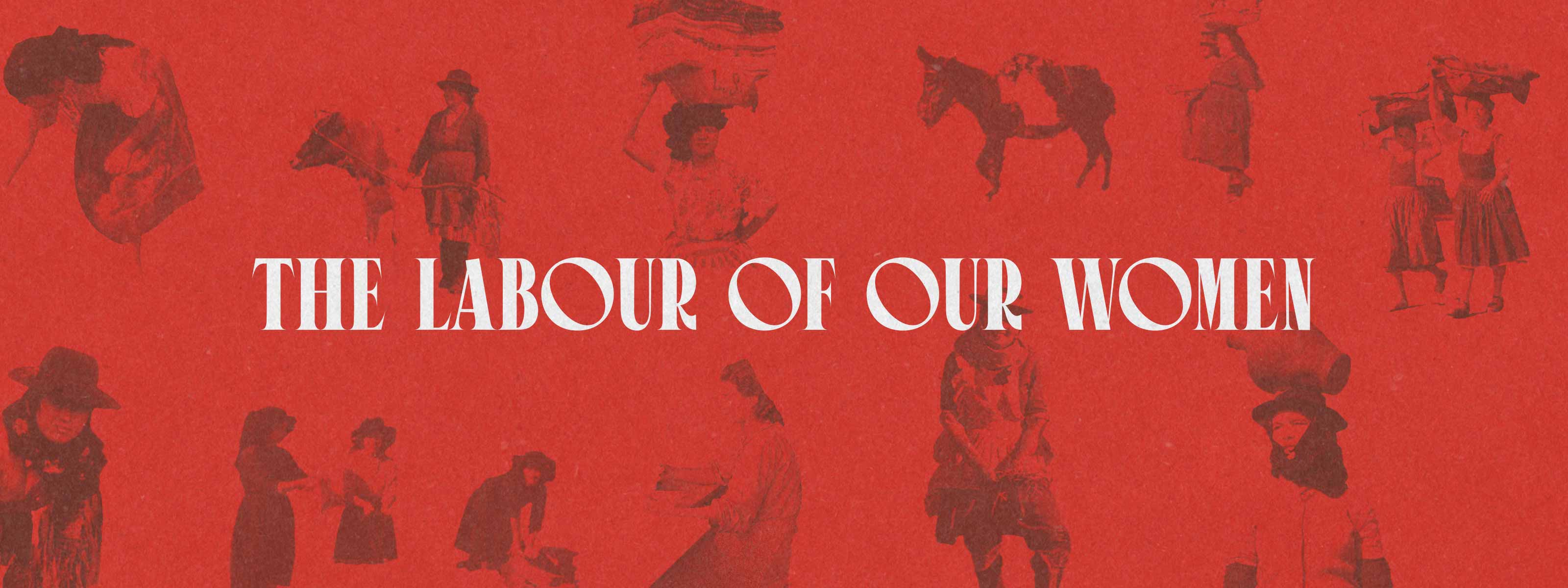

The labour of our Women

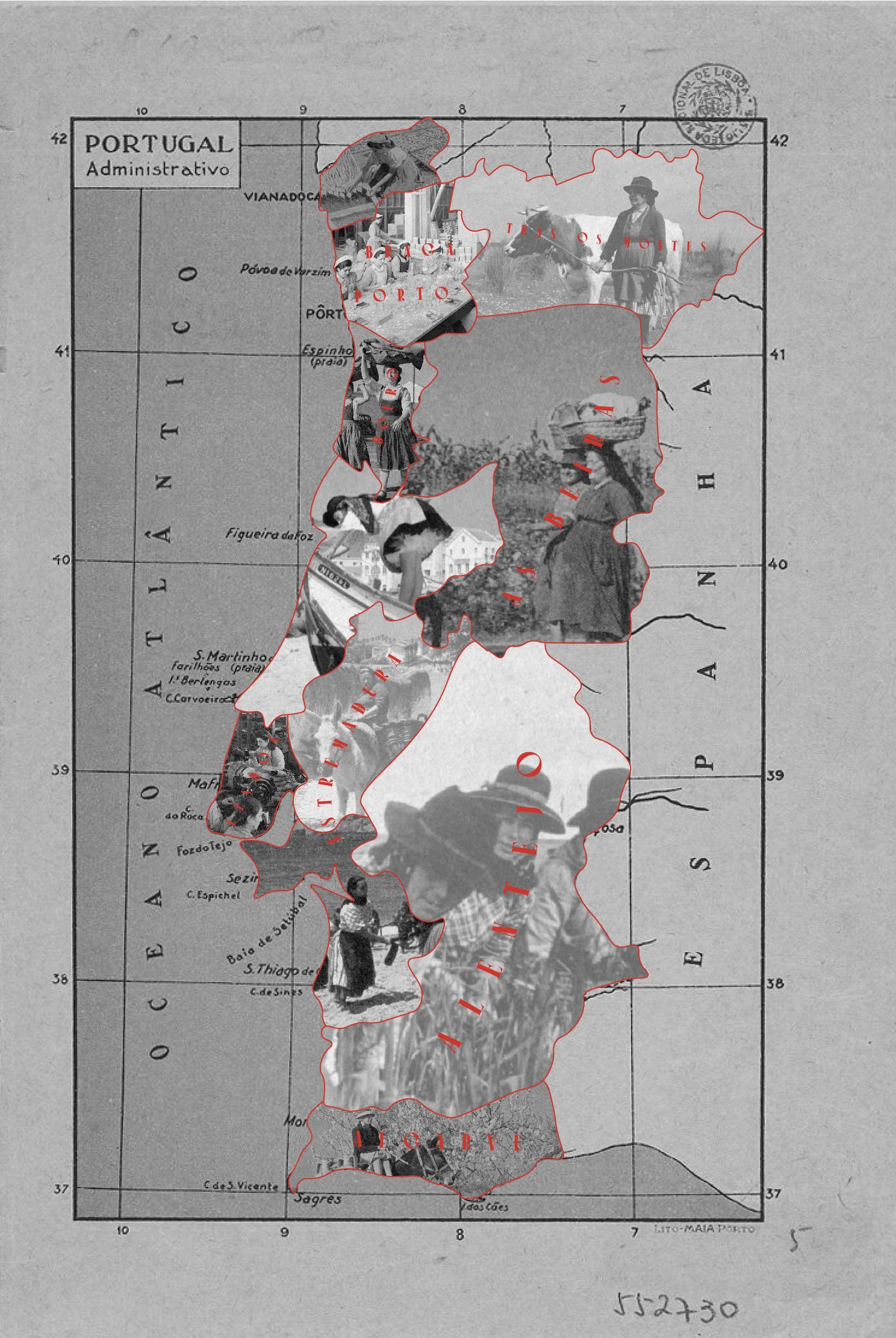

Virtual exhibition inspired by the recent exhibition Maria Lamas and her women, presented at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and curated by Jorge Calado.

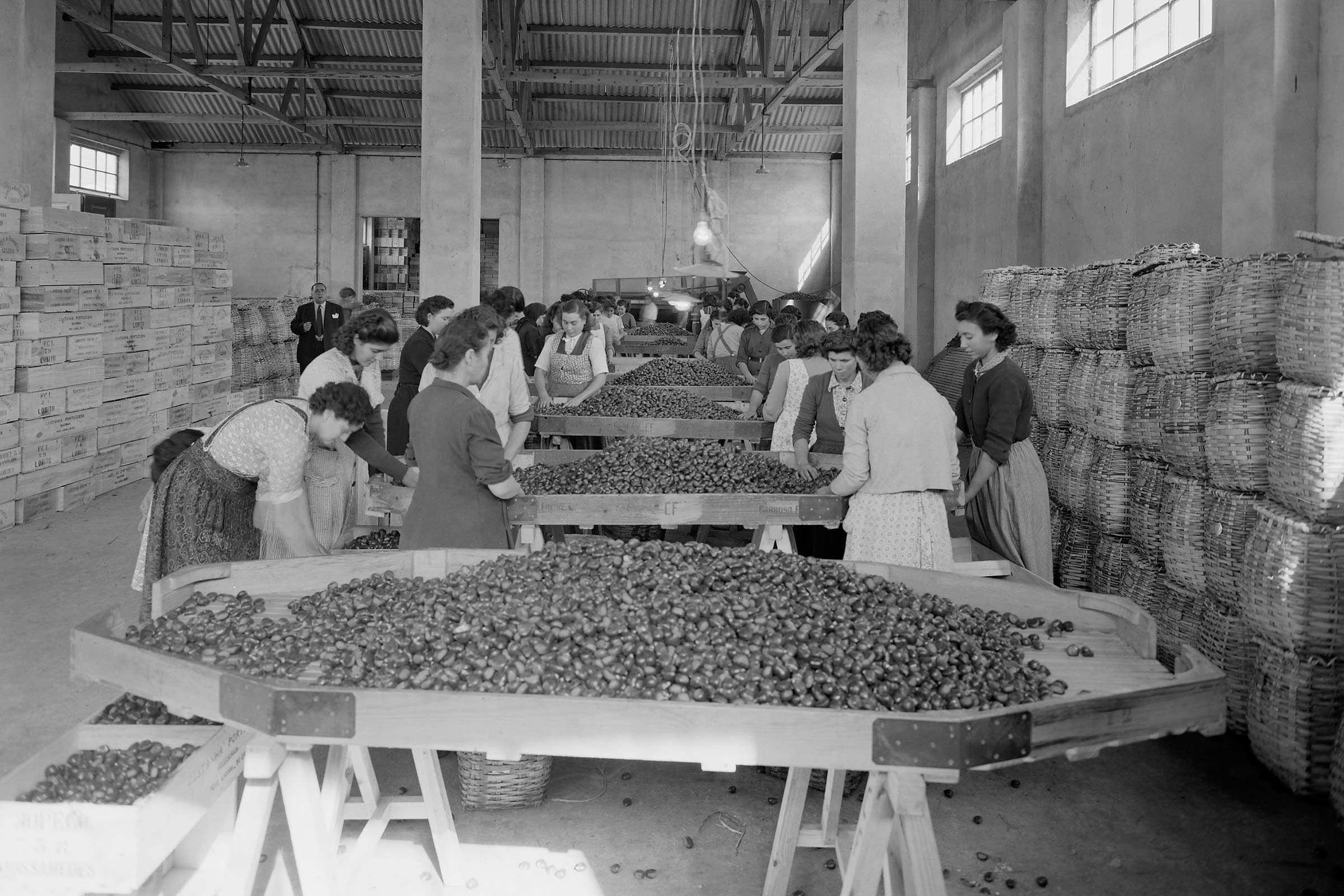

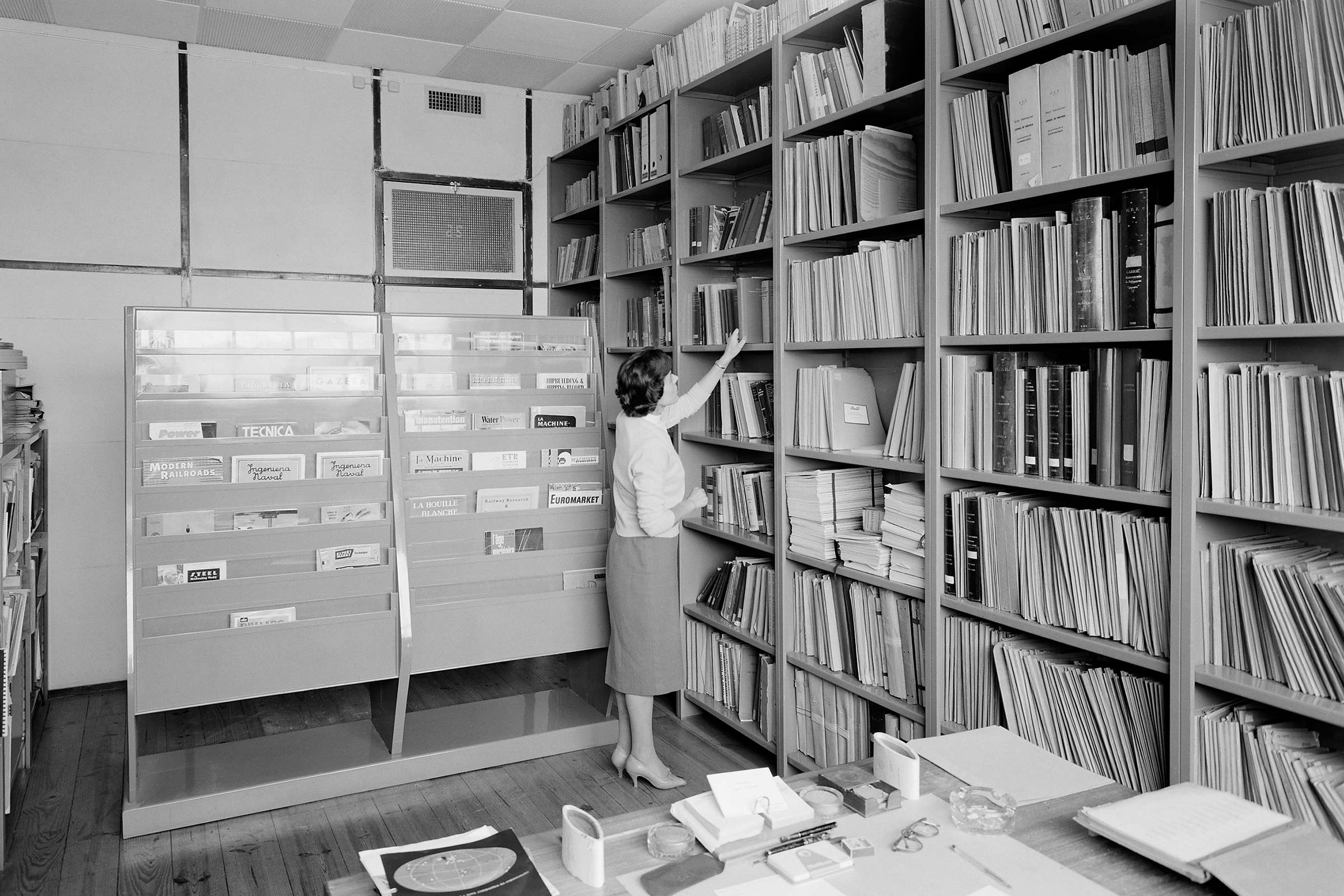

Using photographic images from the Art Library’s collections, this exhibition aims to reveal fewer known aspects of the world of women’s work in Portugal in the 20th century, with an emphasis on the period of the Dictatorship.

Images from the Portugal in colour collection, which includes 753 anonymous photographs (35 mm), images taken by photographers Mário and Horácio Novais between the 1940s and the 1960s, and images by the photographer Abreu Nunes were chosen as sources for this reflection.

This research resulted in an appreciable number of photographs depicting women in the most varied labour tasks, both in rural areas and in urban areas. The connection between women and work is the main theme of this photographic exhibition, which will take us all over the country.

In addition to the photographs, this virtual exhibition includes a series of videos featuring interviews with Emília Ferreira (researcher and curator), Joana Ralão (researcher), and Raquel Freire (filmmaker), in which these authors present their reflections and viewpoints on the topic of Portuguese working women during the 20th century.

Women in the Estado Novo – the “fairy of the family home”

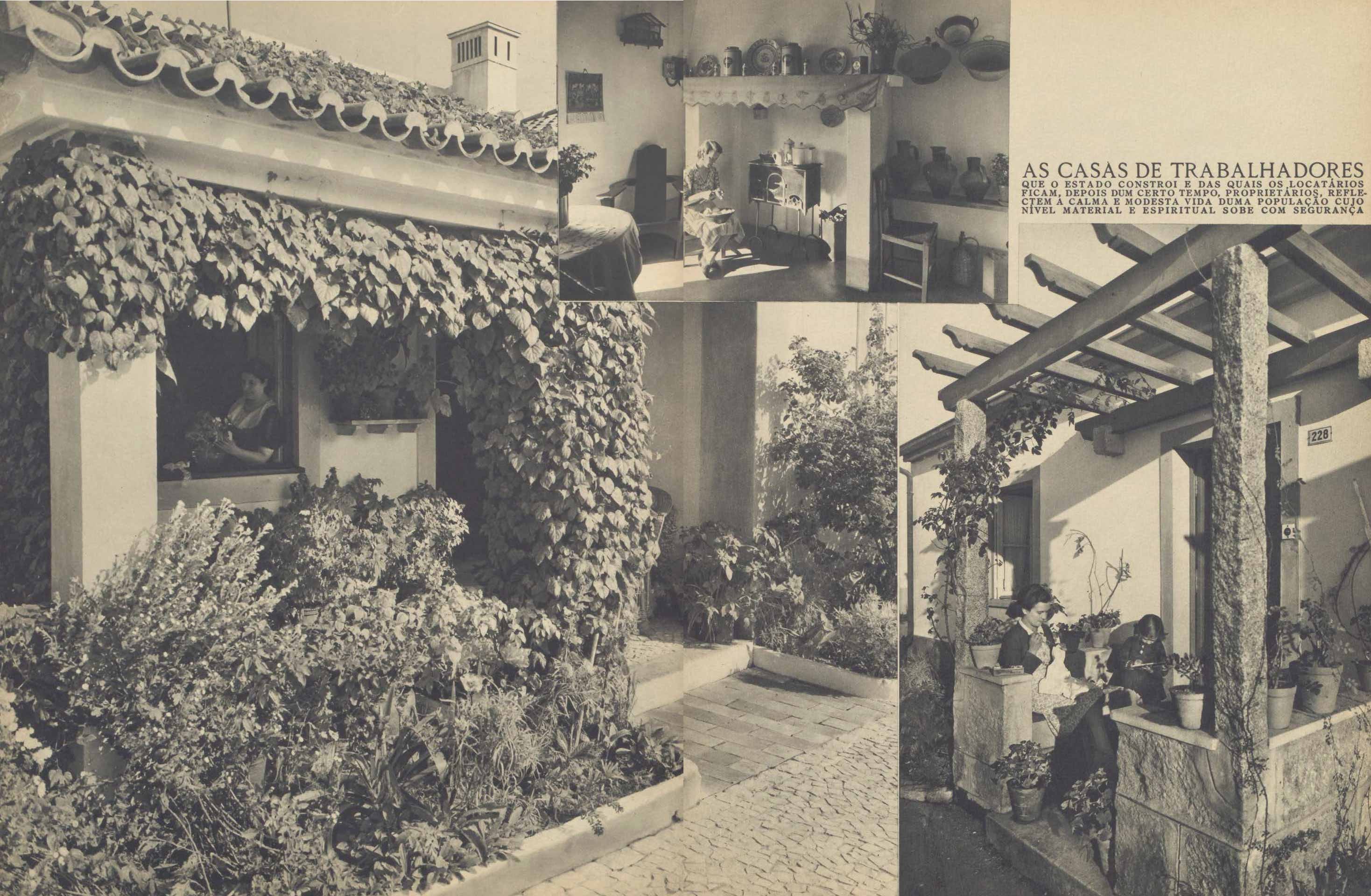

The Estado Novo expected women to be essentially “fairies of the home” and “pillars of the family”, in other words, dedicated wives, extreme mothers and exemplary housewives.

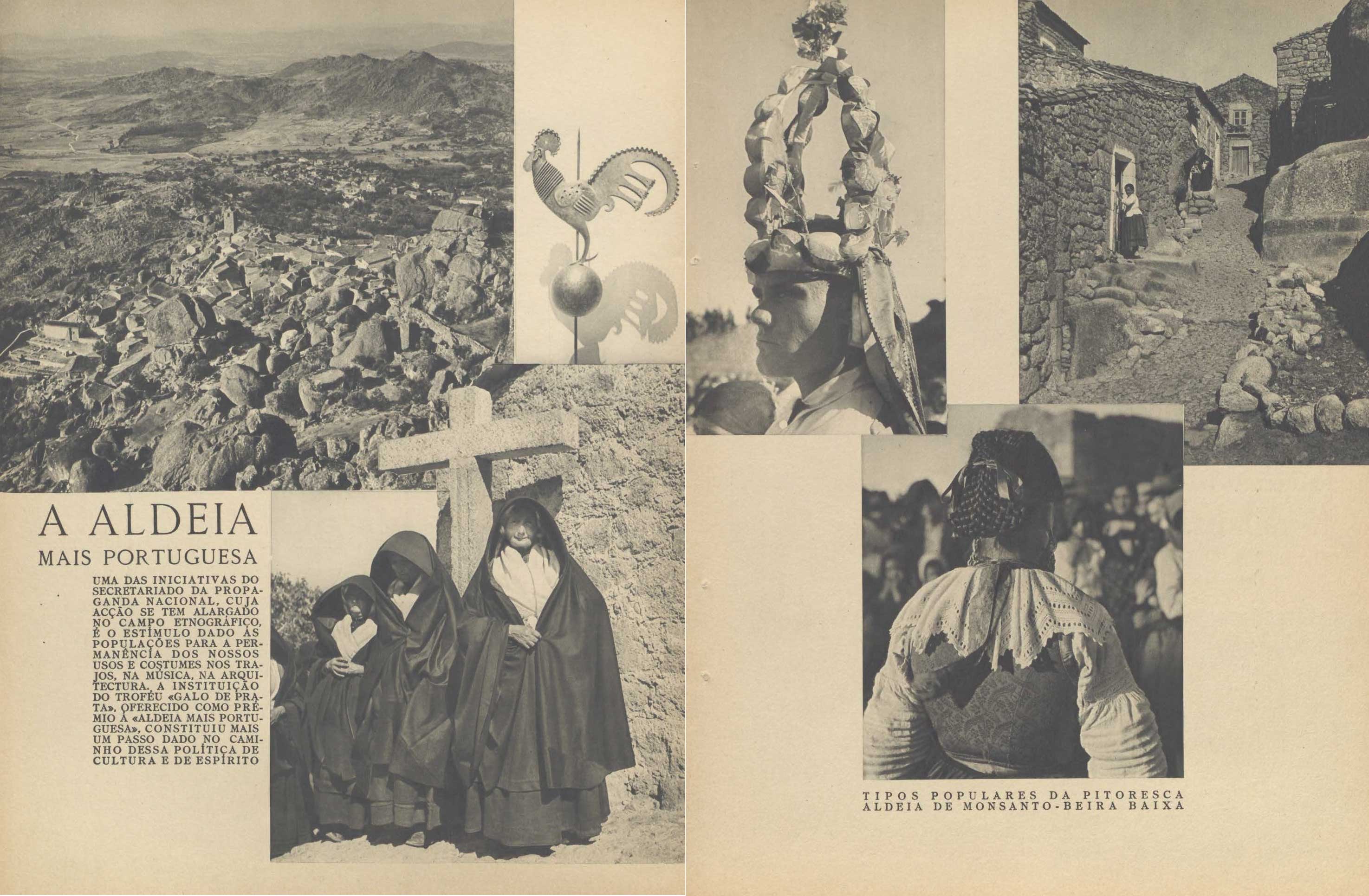

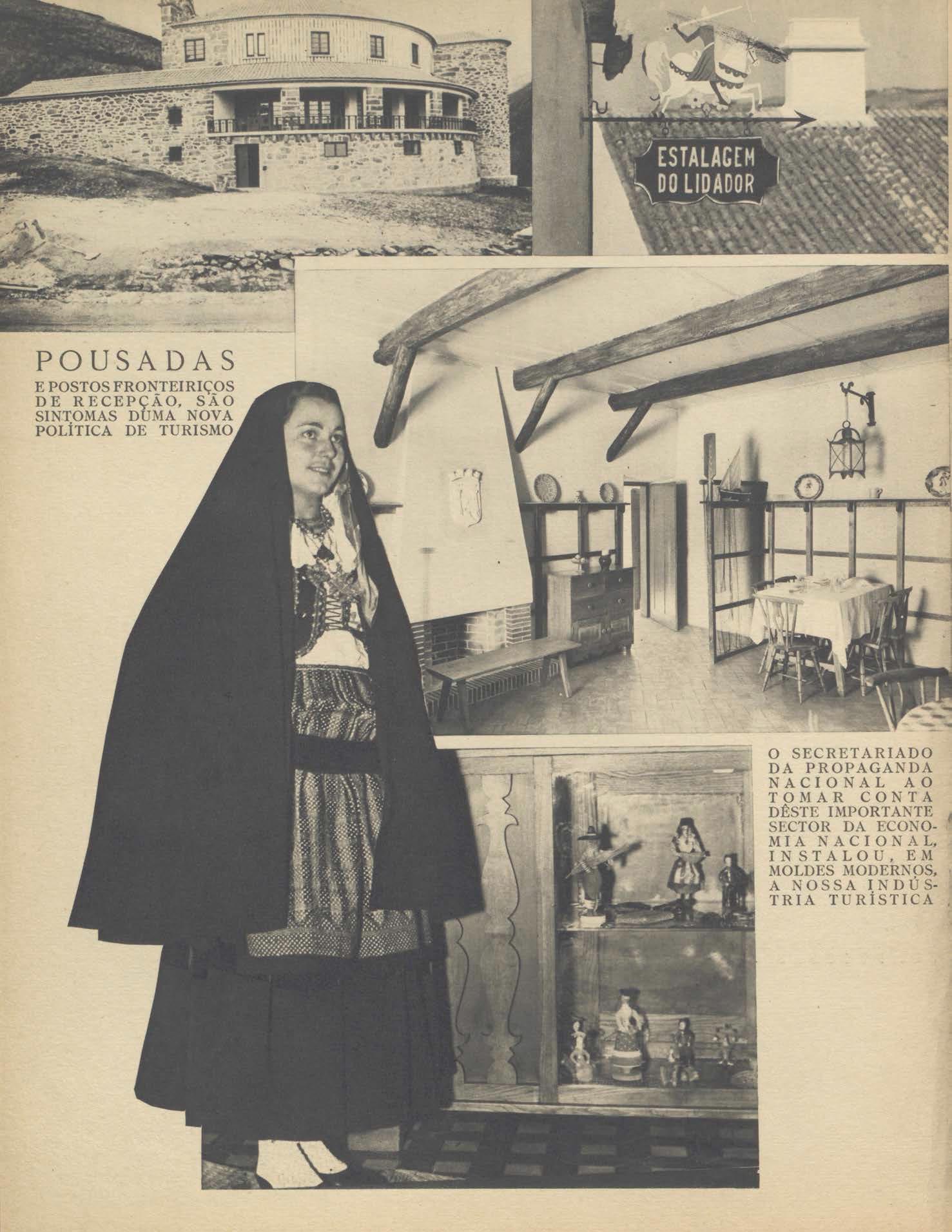

These were the roles that appeared in the narratives disseminated by the National Propaganda Secretariat (SPN) and in the speeches of the dictator António de Oliveira Salazar. In fact, this ideology, inspired by conservative Catholic morals, confined women to the domestic sphere and forbade them from playing any role in the public sphere. However, the reality experienced in the country was very different and diverged significantly from this idealistic portrayal of the situation of women in society.

The Constitution of the Estado Novo, which lasted from 1933 until the April 1974 Revolution, established the subordinate role of women in society, in line with the Civil Code in force, dating from 1867. In Article 5, which set out the principle of equality between citizens under the law, an exception was made: women were denied the right to hold public office due to their biological differences and their fundamental role in the well-being of the family. In other words, from 1933 onwards, women’s ability to work outside the home was severely restricted (also by the National Labour Statute of the same year).

This exception had far-reaching social implications, perpetuating a notion of women’s inferiority and relegating them to a secondary role in society and the family structure, in a legacy that continues to outline our understanding of gender roles in the 21st century.

The everyday reality: working women

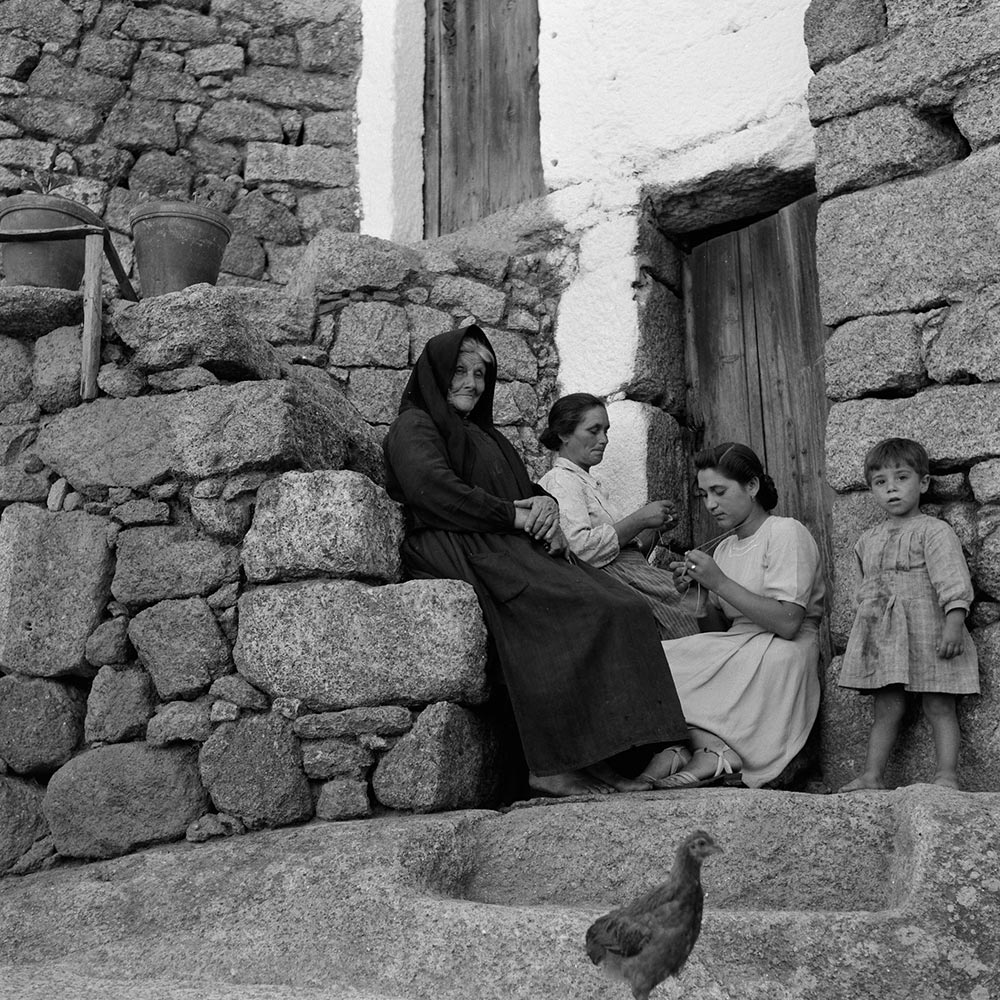

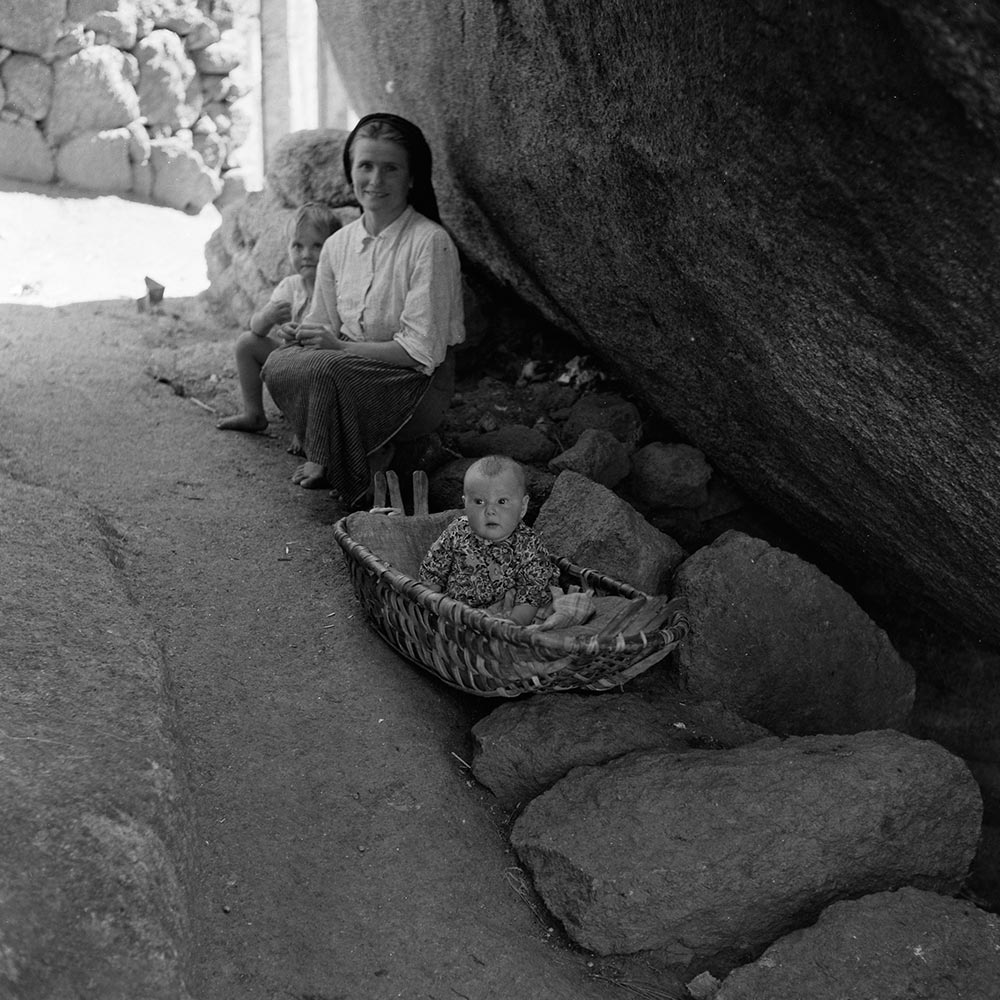

Whether in the countryside or in the cities, Portuguese women have always worked in addition to their domestic activities, contradicting the image promoted by the Estado Novo.

From the early 1960s onwards, the increase in male emigration and the colonial war amplified the obligation for women to work to support the family. The women who didn’t have the necessity to work – inside or outside the home – belonged to the families of the regime’s economic and social elite.

In their interviews, the three invited guests mention the diversity of women’s professions in the various regions of Portugal during the Estado Novo period.

In coastal areas, the most common professions were associated with maritime and fishing activities; inland, agriculture and farming dominated, complemented by handicrafts; in cities, women worked in factories, hospitals, services and commerce; in border areas, they also collaborated with their partners in activities related to smuggling.

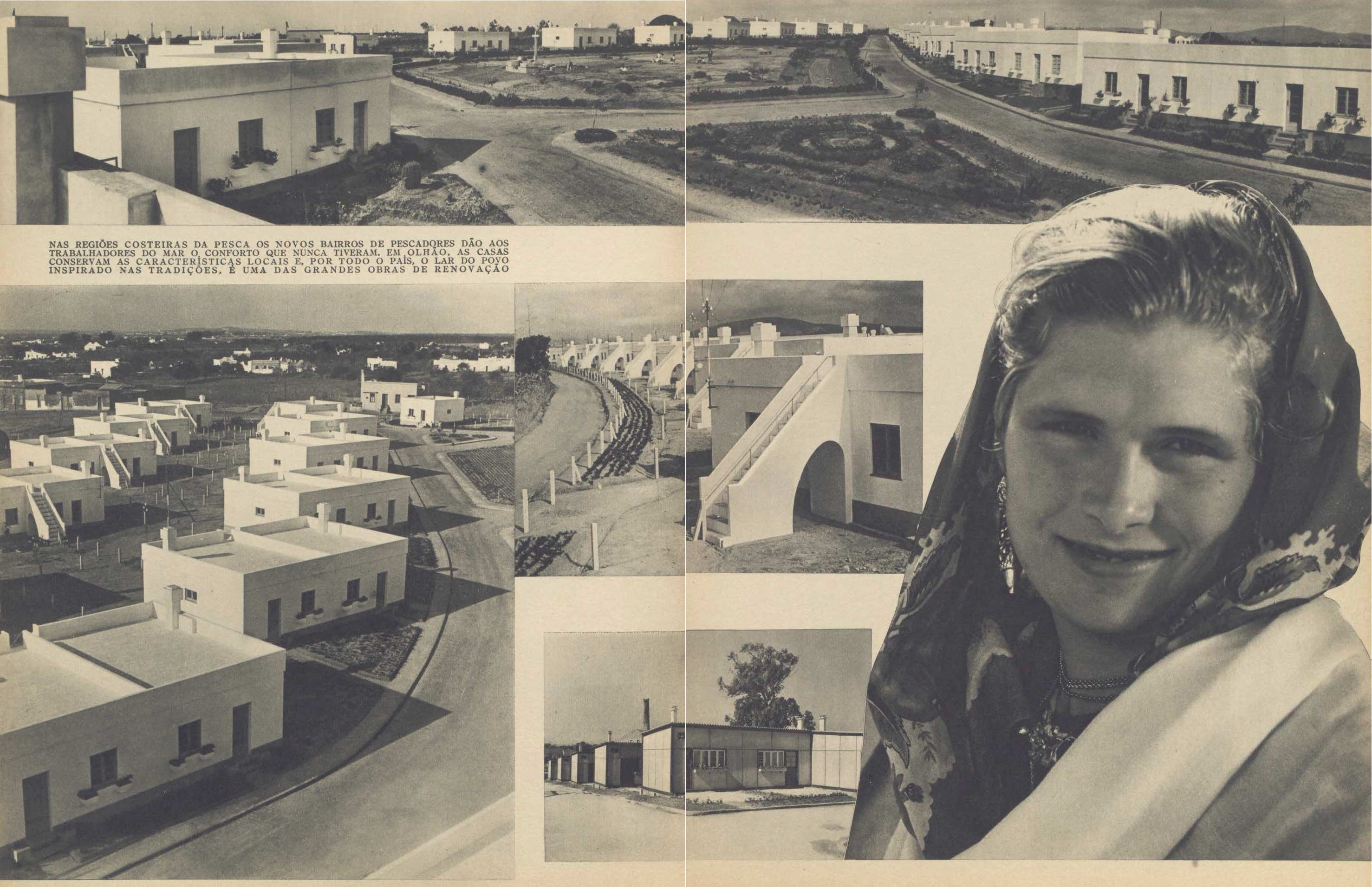

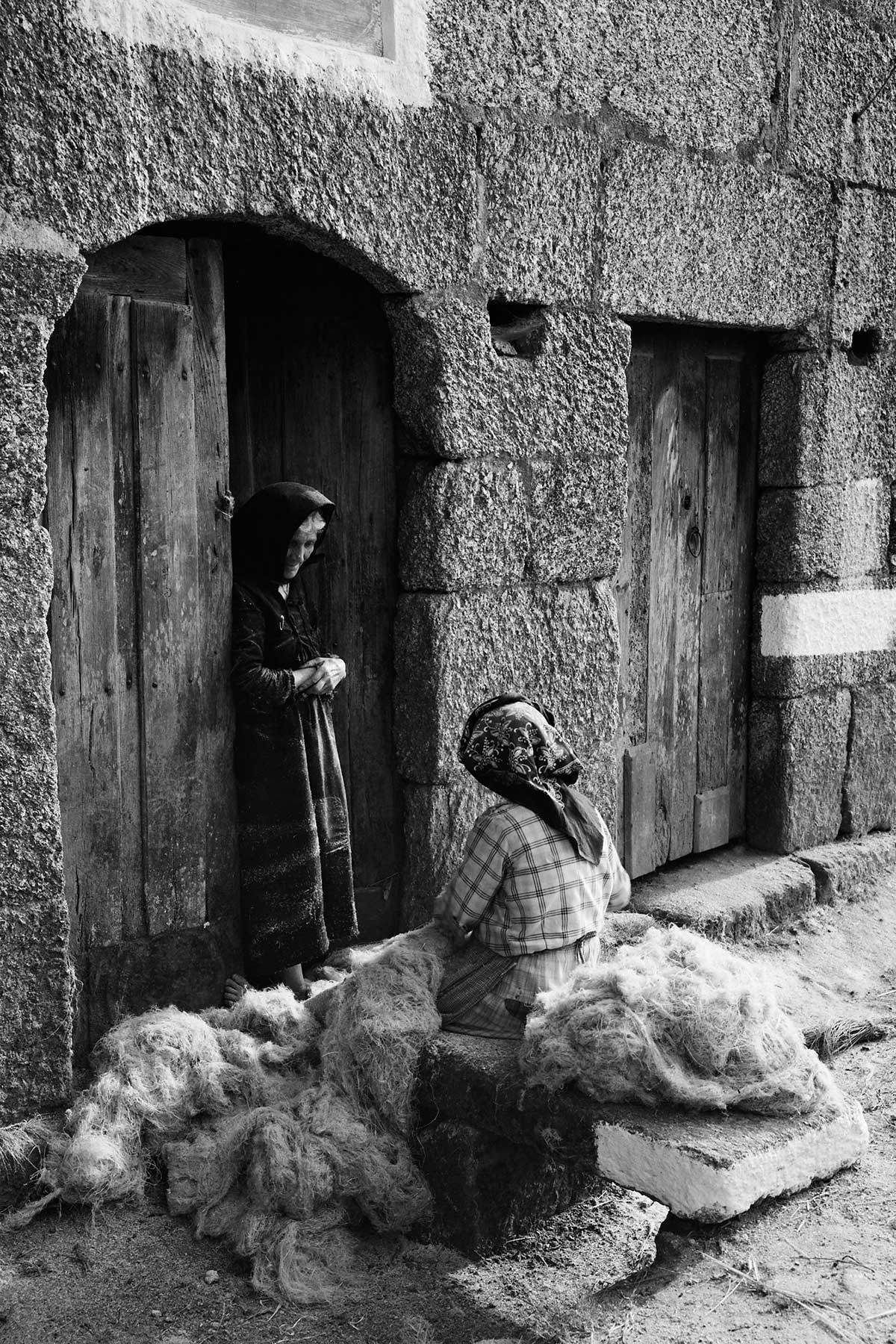

In the coastal areas, women were a fundamental part of fishing activities. Although they weren’t usually part of the crews that set out to sea, they helped transport the boats to shore and repair the nets, and they were the ones who sold the fish, dried it and worked in the canning industry.

In some localities, women were also involved in handicrafts, such as the hats and baskets made by the women of Aveiro and the bobbin lace made by the women of Vila do Conde and Peniche.

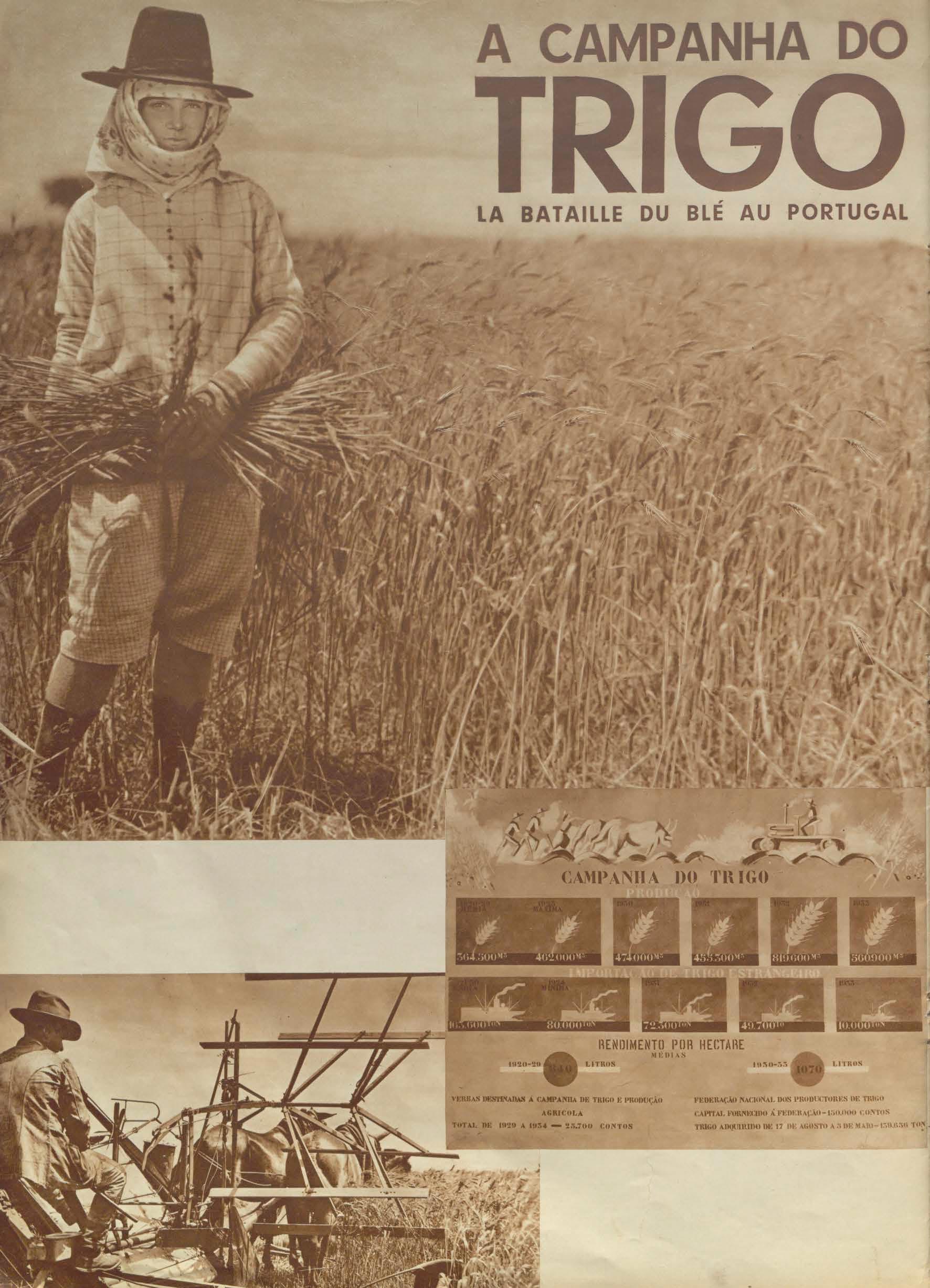

In the fields of the Alentejo, women worked harvesting cereals and picking olives. In the Ribatejo, it was the rice cycle that occupied them. In the Douro and Minho, vineyard work predominated, and in Trás-os-Montes and the Beiras, agricultural labour was joined by pastoral work. In the archipelagos of Madeira and the Azores, the cultivation of tea and tobacco was not done without female labour. In other words, in all regions of the country, women worked hard and shared the hardship of agricultural labour and difficult living conditions with the rest of the family.

Since the end of the 19th century, Lisbon and Porto have been the two Portuguese cities with the largest number of manufacturing units. In the case of Lisbon, the factories were distributed throughout the city, with a greater concentration in the Alcântara area and in the eastern part. In the coastal regions of the country, north of the Mondego River and in the Algarve, there were several canning factories, and in the Beira interior area there were important manufacturing centers linked to textile production.

The professions considered appropriate by the Estado Novo for the supposedly fragile and maternal nature of women were, as you can imagine, those that could be related to these characteristics: governesses, servants, nurses and teachers.

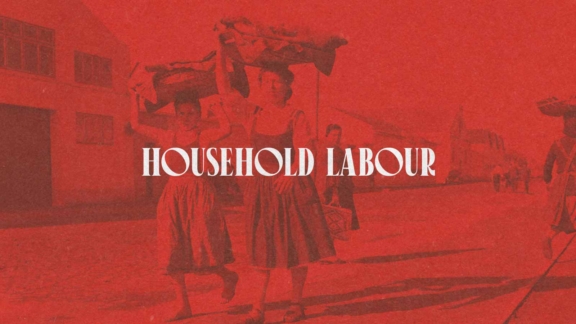

Throughout the ages, and in different societies and cultures, the “home” has been an invisible workspace for women and, paradoxically, a space of some freedom and power.

As the popular saying goes, “She’s in charge at home, but I’m in charge of her”. As well as managing household and family affairs, the home was also the place where they could carry out other activities, such as sewing, which allowed them to contribute to the family economy. Social acceptance of women’s ‘natural’ aptitude for domestic tasks was built on religious views, political convictions and reinforced by the exclusion that women suffered for many centuries in terms of access to education. Unfortunately, in some parts of the world, this is still the situation experienced by many girls and women.

The working woman in today’s Portugal

What is the impact of the feminine ideal promoted by the Estado Novo over 48 years on Portuguese society in the new millennium? In what way are the differences in salary that continue to exist between men and women, as well as the lack of recognition of domestic tasks, still impregnated and perpetuating this conservative ideology? In addition to these questions, there are others related to sexual harassment and the difficulty women have in reaching management positions in the country’s economic and political spheres. What are the “labours” of Portuguese women today?

Credits

Curatorship

Enrico Porfido and Juan Gonzalez del Cerro

Art direction and graphic design

Juan Gonzalez del Cerro

Documentary research

Ana Barata and Enrico Porfido

Proofreading

Ana Barata

Edition

Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation – Art Library and Gulbenkian Archives

Acknowledgments

The curatorial team would like to thank Emília Ferreira, Joana Ralão, Raquel Freire and Fernanda Rollo, as well as the research network “Resistência no Feminino” and the Memória para Todos project of the Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

Memória para Todos is a project that promotes the research, organization and dissemination of Portugal's historical, cultural and technological heritage. The content gathered with the participation and involvement of citizens and institutions is made available online in open access. Here are some of the testimonies collected from across the country, in which women tell us about their history and their experiences of working during the Estado Novo.

Videos

Curatorship

Enrico Porfido and Juan Gonzalez del Cerro

Participation

Emília Ferreira, Joana Ralão and Raquel Freire

Biographies

Emília Ferreira

She is an art historian, literary critic, art critic, lecturer, curator of visual arts exhibitions and educator. She has collaborated with the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation's Centro de Arte Moderna and was a member of the Casa da Cerca – Contemporary Art Centre team (2000-2017). Since 2017 she has been Director of the National Museum of Contemporary Art – Museu do Chiado.

Joana Ralão

She has a degree in History from the Faculty of Social and Human Sciences of Universidade Nova de Lisboa and a Master's in Contemporary History from the same institution. In her master's thesis she studied the presence and participation of women in the student movement of the 70s. She is an integrated researcher at the HTC – History, Territories and Communities at NOVA-FCSH/CFE.

Raquel Freire

She is a director, screenwriter, writer, producer and mother. Her films Rio Vermelho, Rasganço, Esta é a minha cara, Veneno cura, Dreamocracy have premiered at international film festivals such as Venice, Turin, São Paulo, Montreal, Leeds, Clermont-Ferrand, Porto PosDoc and in cinemas. She directed and produced the trilogy Stories of the women of my country, which aired on RTP1. She directed and produced the film Women of my country. She is currently directing the film and series Women of April.