- 1993

- Wood and Plaster

- A definir

- Inv. 94E340

José Pedro Croft

S/ Título

In 1993, José Pedro Croft created a series of sculptures using coupled objects that were based on the memory of spaces inhabited on a daily basis, such as the home or the studio, and the tensions created by the apparent familiarity of the objects contained in them, which are only casually and fleetingly touched. The work shown was one of two that were displayed at a solo exhibition staged in 1994 by the CAM, after which it came to form part of the collection.

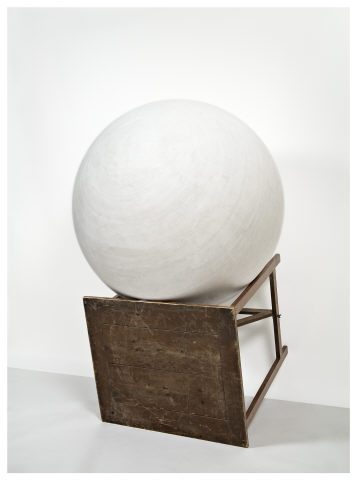

In the white sphere resting on the inclined wooden table, Croft, in concordance with his generation, puts forward a critique of the idea of the monument, an essential category in the tradition of Western sculpture. Although it obeys a conventional heterogeneous logic in which the pedestal (the table is to be seen as the supportive body/base/column) supports, elevates, and ennobles the sculpted material (the plaster marked by the rhythmic gesture of the modelling), the work subverts the gravitational logic of the whole by evoking the imminence of a fall. In the fragile equilibrium dependent on the directional forces acting on the juxtaposed bodies, which are in dramatic spatial competition, the collapse is inevitable. Crystallising the moment prior to the encounter between the sculpture and the ground, the work holds the desire for this encounter in the disquieting announcement of the predictability of the fall. Strongly architectural in nature, the piece sustains provisional relations of space, on the outline projected in light and shade on the wall, and interrogates, in the staging of its binary economy, the meaning of the installation.

As both container and content, its elements deny and confirm the sculptural quality of the materials. Its dual characteristics (organic and inorganic, expressive and inexpressive, light and dark, old and new, figurative and abstract, or trivial and auratic) constitute structural paradoxes which lend harmony and order to its presence.

The minimalist efficacy of the white sphere, reflective reservoir of luminous matter, is revealed in the perception of a time and a space that constitutes a protective wrapping, in a silent and ritualistic emotional experience. Without returning to the extreme strangeness of the funerary experience (a characteristic of Croft’s work in the 1980s), an austere monumental sacredness is present here.

Lígia Afonso

May 2010

| Type | Value | Unit | Section |

| Height | 170 | cm | |

| Width | 110 | cm | |

| Depth | 130 | cm |

| Type | Acquisition |

| Hors Catalogue - Un projet Gulbenkian à propos de sa collection |

| Amiens, Maison de la Culture d'Amiens, 1997 |

| ISBN:2 903082 70 8 |

| Catálogo de exposição |

| A Partir da Colecção |

| CAMJAP/FCG |

| Curator: CAMJAP/FCG |

| 25 Julho de 2006 a 29 Abril de 2007 Museu do CAMJAP - Piso 01 |

| Comissariado: Jorge Molder e Leonor Nazaré |

| Hors Catalogue - Un projet Gulbenkian à propos de sa collection |

| CAMJAP/FCG |

| Curator: João Fernandes |

| Dezembro de 1996 a Fevereiro de 1997 Casa da Cultura de Amiens, França |

| Uma co-produção da Casa da Cultura de Amiens e do Serviço de Belas-Artes e do CAMJAP da Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.Esta exposição tem origem numa proposta de Augusto Rodrigues da Costa, responsável pela programação de artes plásticas da Casa da Cultura de Amiens. |

| Exposição Permanente do CAM |

| CAM/FCG |

| Curator: Jorge Molder |

| 18 de Julho de 2008 a 4 de Janeiro de 2009 Centro de Arte Moderna |

| Exposição Permanente entre 18 de Julho de 2008 a 4 de Janeiro de 2009. |