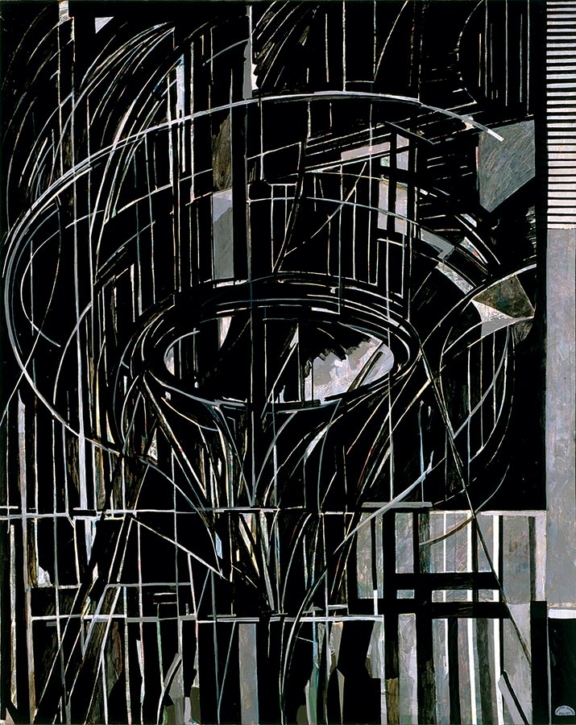

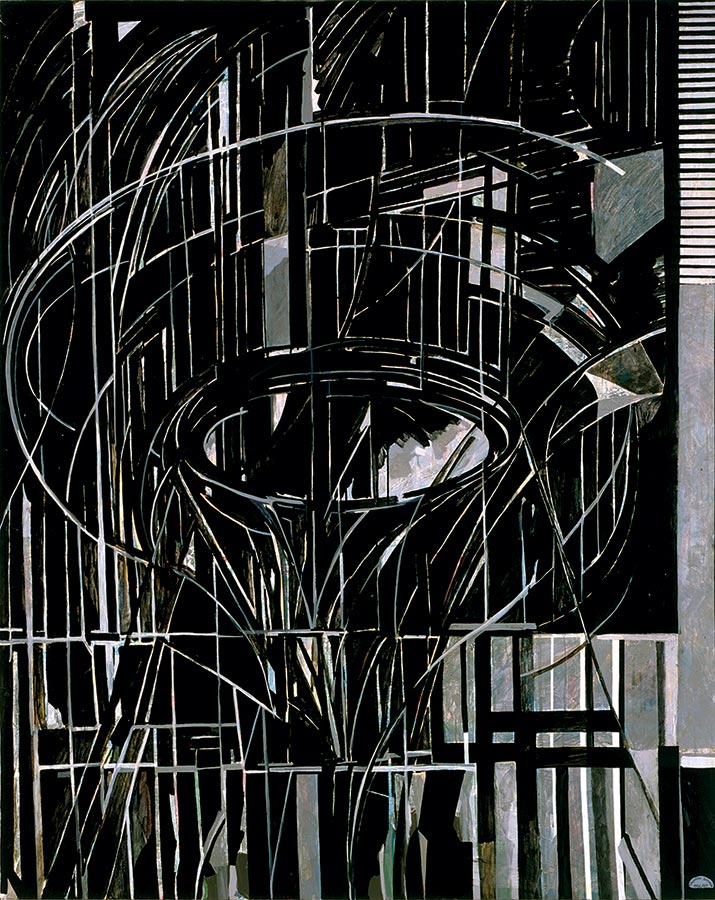

In the 1980s Eduardo Batarda stopped painting in watercolours and returned to using acrylics. He also abandoned the explicit figurative allusions in his work, as well as the verbal inscriptions, though occasionally he would insert a syllable or letter in one of his paintings. The work Nectar was bought by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation after Batarda received an honorary mention at the Third Exhibition of Fine Arts at the Foundation (1986). As opposed to other paintings made after his return to acrylics, all improvisations in various layers of paint, for this work Batarda made a preparatory drawing. But otherwise the artist deploys the same process of pictorial construction through palimpsests. This consists of an initial layer in which he uses various colours, and possibly even some form of figuration, which are then covered in semi-transparent white paint. Over this layer, dark tones are applied – blacks or greys and browns (in some later paintings, he uses blues and greens). In the oscillation between revealing and masking the underlying layers, these colours draw vertical, horizontal or elliptical lines. On the bottom left corner of this painting, these forms become optical devices camouflaging the fact that the stretcher is out of alignment. To finish, a layer of varnish seals the pictorial surface.

As with his earlier work, the artist continues to invite the viewer to approach and retreat from the work in order to see it. It is from close on that that the pale, underlying colours can be seen, like ghosts of the original painting. Nectar is an example of an archaeological exercise of painting that Batarda undertook systematically from the 1980s on, in which he comments on a dead or dying painting (because painted over), while at the same time each of these exercises is the ironical prove that, in fact, it continues alive. The vortex that we see in the initial reading of the work – in other words, in our apprehension of the last layer to have been painted – does remember the idea of an abyss or collapse, already present in the early watercolours, but also evokes optical illusions and viewing devices, such as tubes, telescopes, spectacles, funnels or peepholes. It is as if painting itself, simultaneously the object and subject of vision, were a device to see itself as something from the past, in order to make itself present.

Mariana Pinto dos Santos

May 2010