The Carnation Revolution in one work from CAM’s Collection chosen by writer Bruno Vieira Amaral

We invited one of the most acclaimed writers of his generation, Bruno Vieira Amaral, José Saramago Prize winner, literary critic and short story writer, maker and lover of literature, to share with us a previously unknown story.

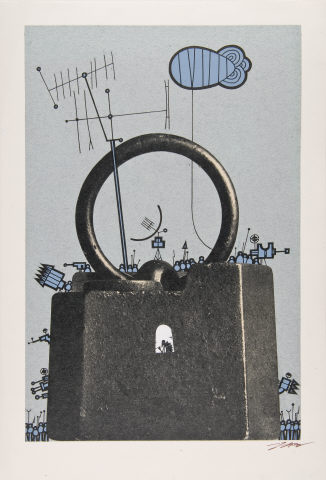

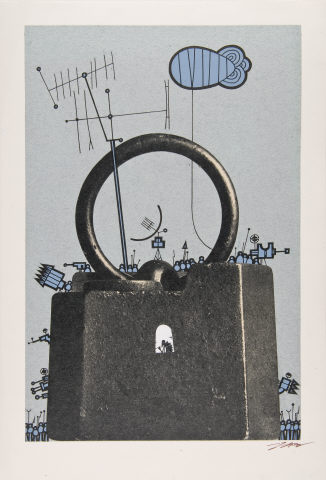

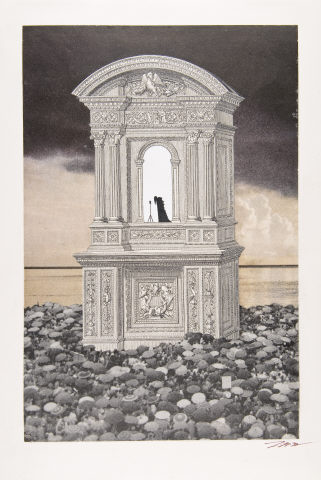

‘Prisioneiro!’, by João Abel Manta

It was during a visit to the Crystal Palace gardens, with their life-size dinosaur replicas, that José Cardoso Pires came up with the idea for ‘Dinosauro Excelentíssimo’. At the time, the writer was teaching in England. Salazar had already fallen off his chair and those around him were selling him the illusion, cruel or charitable, of his perpetual power. In the form of letters to his youngest daughter, Rita, this adventure in the Mussel Kingdom was born, governed by a young boy of humble origins who became a capital-D Doctor in the city of capital-D Doctors and ended up becoming a “Most Excellent Emperor”, a parser of paragraphs, a purifier of language, a lover of so-called severe bureaucracy, and a preacher of the virtues of poverty, also known as humility or modesty.

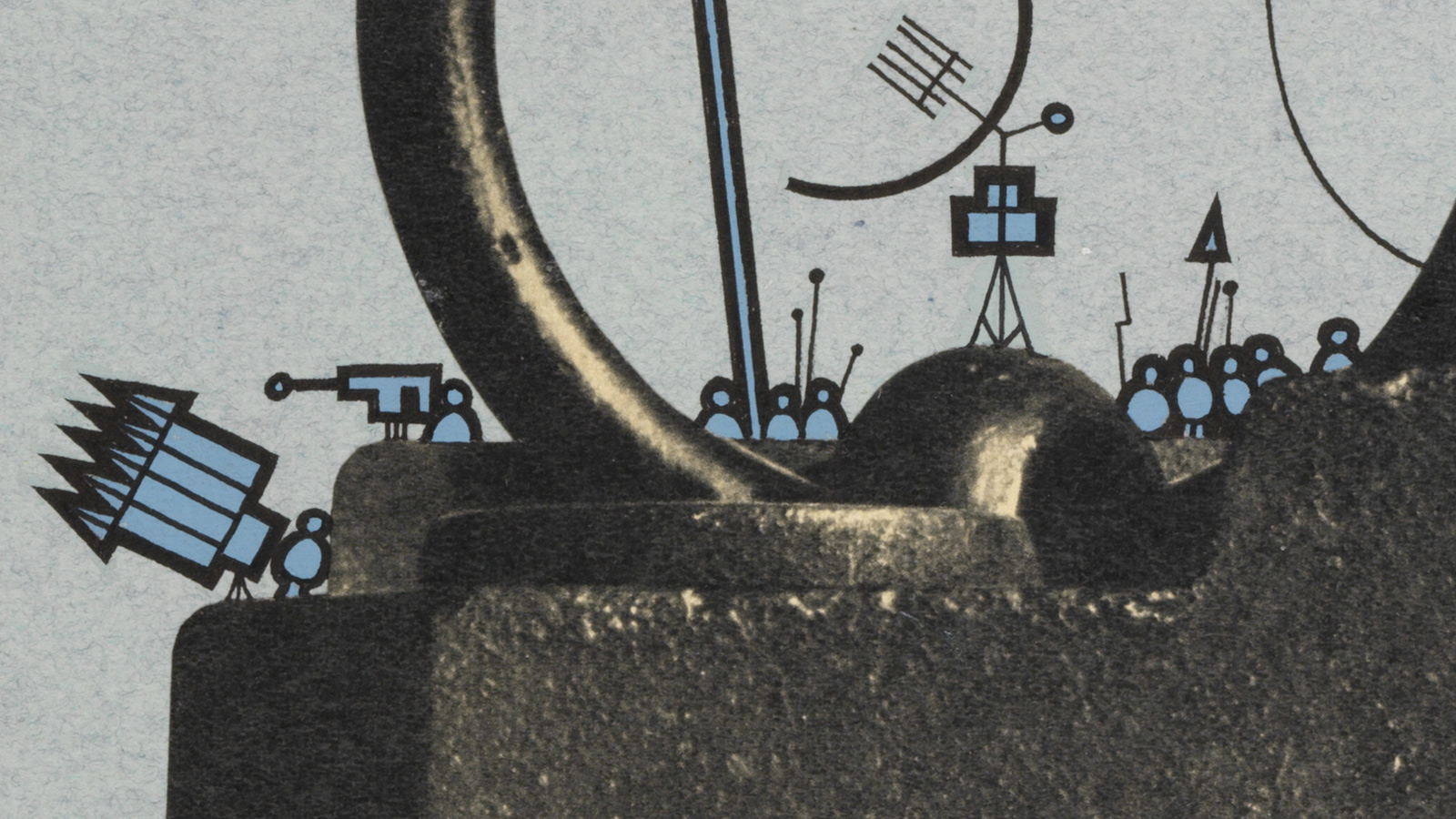

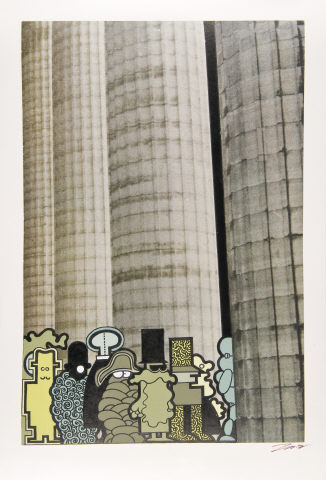

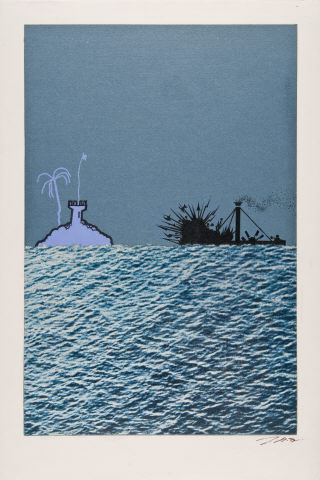

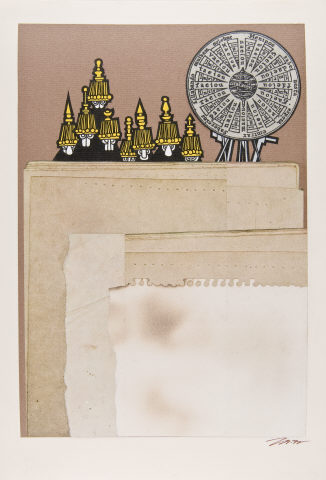

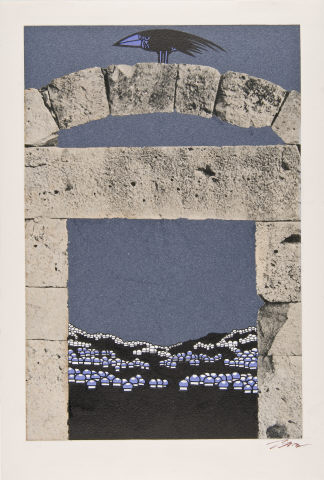

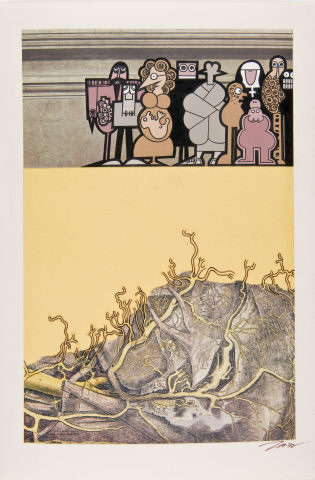

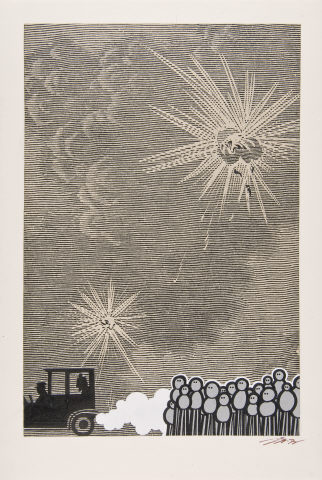

Cardoso Pires challenged his friend João Abel Manta to illustrate the book after the real-life version had kicked the bucket. And if text and illustration complement each other, it would be criminal to reduce the artist’s work to the category of a mere graphic complement. From the illustration on official blue paper of twenty-five lines to show the humble cottage where “Dinosaurus I” was born (a way of emphasising the construction of official historical truth) to the biblical epic of the peasant couple taking their little son, born on a bed of humble straw, in their van to study in the city of doctors, João Abel Manta had the gift, as Cardoso Pires did in text, of a sarcastic eye capable of holding to ridicule the grand narrative of power, the relentless repeated rhetoric of a country small in every way, the progressive isolation of its leader, and the arrogance of his followers.

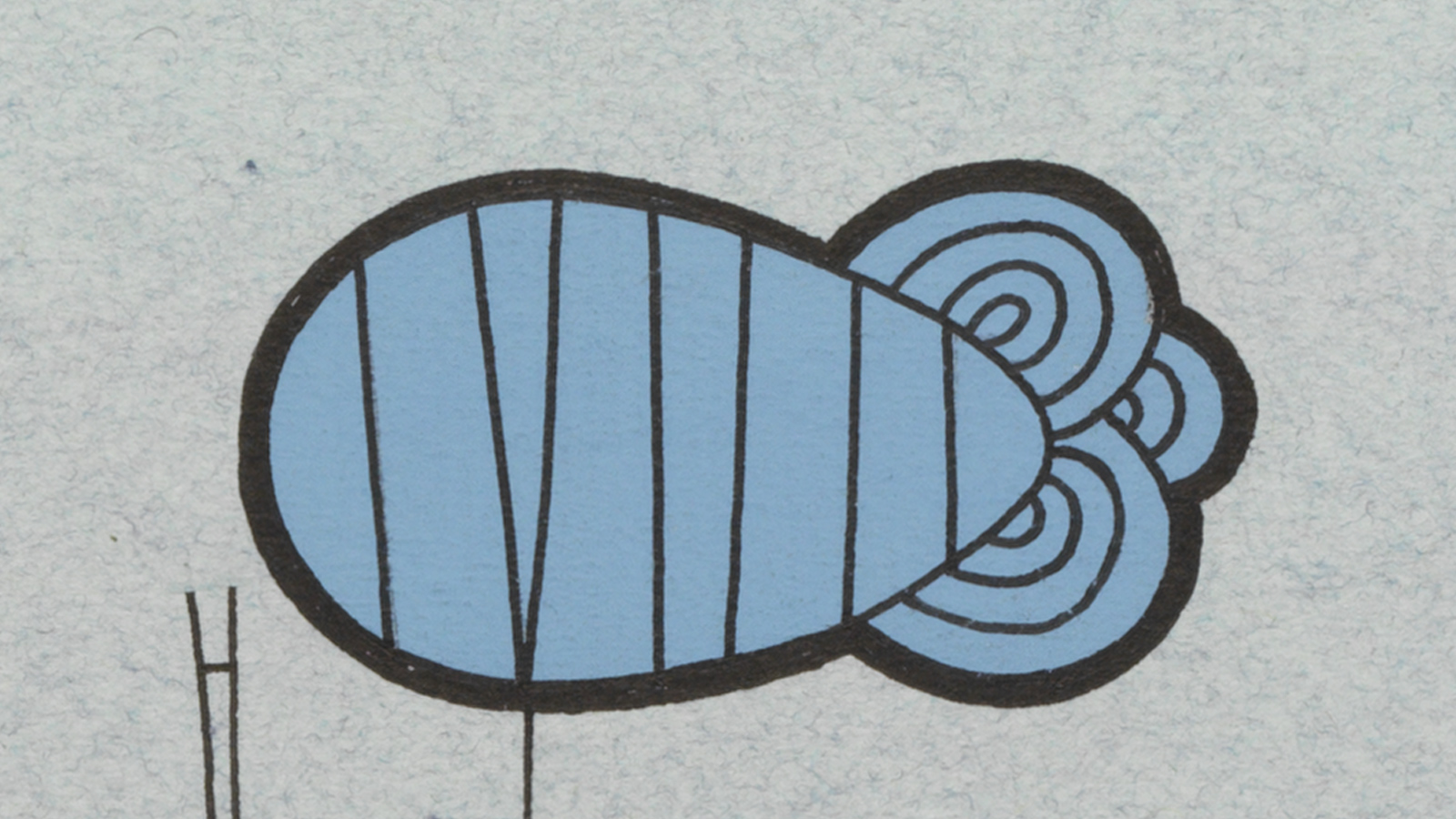

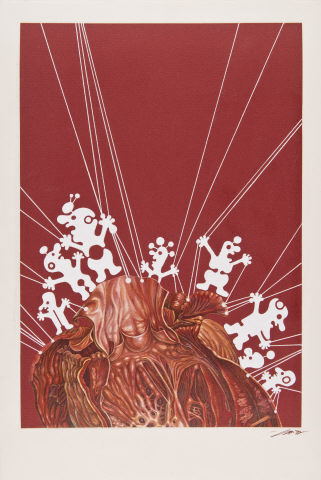

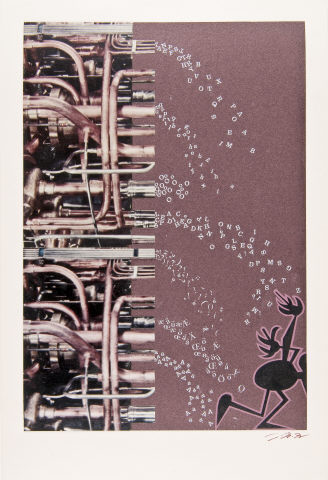

Enclosed in a kind of anvil topped by broadcasting devices, the Emperor lives permanently in armour, protected from all threats but increasingly insensitive to the voices of his fellow citizens or, rather, his subjects, whom he insists on bombarding with speeches that are detached from reality and which empty words of their true value. There is no authentic communication. No dialogue. The Emperor does not speak with anyone, does not deign to listen to anyone. He dictates into a tape recorder and all that he hears are the recordings of his own voice, reciting ideas that emerge ‘on closed circuit’:

‘He listened to them afterwards, or rather, he listened to himself, and, as they say, with a day and night hearing, with the air of a master following the lesson of a beloved disciple.’

The prolonged and autocratic exercise of power inevitably leads to solitude, to the leader closing in on himself, like a moth returning to its larval state. The barriers erected by power to protect itself from the world, to defend itself from the attacks of its enemies, are the walls that delimit its territory and its movements, like a parody of an oriental parable in which a man endeavours to build a fortress only to discover, in the end, that he has erected the walls of the prison where he will serve time for the crime of having built the fortress. An Emperor enclosed in his cocoon. A prisoner of a most excellent nothingness.