‘The building of a world where we will never live in it’s a form of spirituality’

How did you start as an artist? Can you tell me about your trajectory and how it ties in with your biography.

On one hand, I’ve had the most conventional artist upbringing. I grew up in a very bohemian family. My aunt is an artist, my great grandfather was an artist, my mum was an actor and became a casting director, and my dad wrote. So I guess it would have been strange if I wouldn’t have become an artist. But then on the other hand, my professional trajectory is probably quite uncommon in the sense that I didn’t go to art school.

I started a BA in photography but I stopped after two years and I didn’t really ever continue my studies. I guess today it’s seen as an unconventional trajectory, but in the past that would have been really normal. So I think this professionalisation of being an artist it’s seen as kind of an aberration, but it would have been quite traditional to just being born into a family of creative people and then you become one.

I teach on MA level and PhD too and I’ve taught on BA before, and one of the main things that a formal education does is that it teaches you to put together a project and to define the things that you’re working on at a very early stage. I think that not doing that has been really beneficial for me. Although it meant that I had a later start in many ways because I was just working through things and acquiring language as to how to describe what I was doing while making it. But I didn’t have the pressure of questions like: what is your work about?

I remember making work in video in the early 2000s, a time when feminism was very unfashionable, and someone telling me that my work was about gender and I was very upset about that because for me it was about cinema. So the world changes and It kind of sometimes makes place for your work, if you’re lucky.

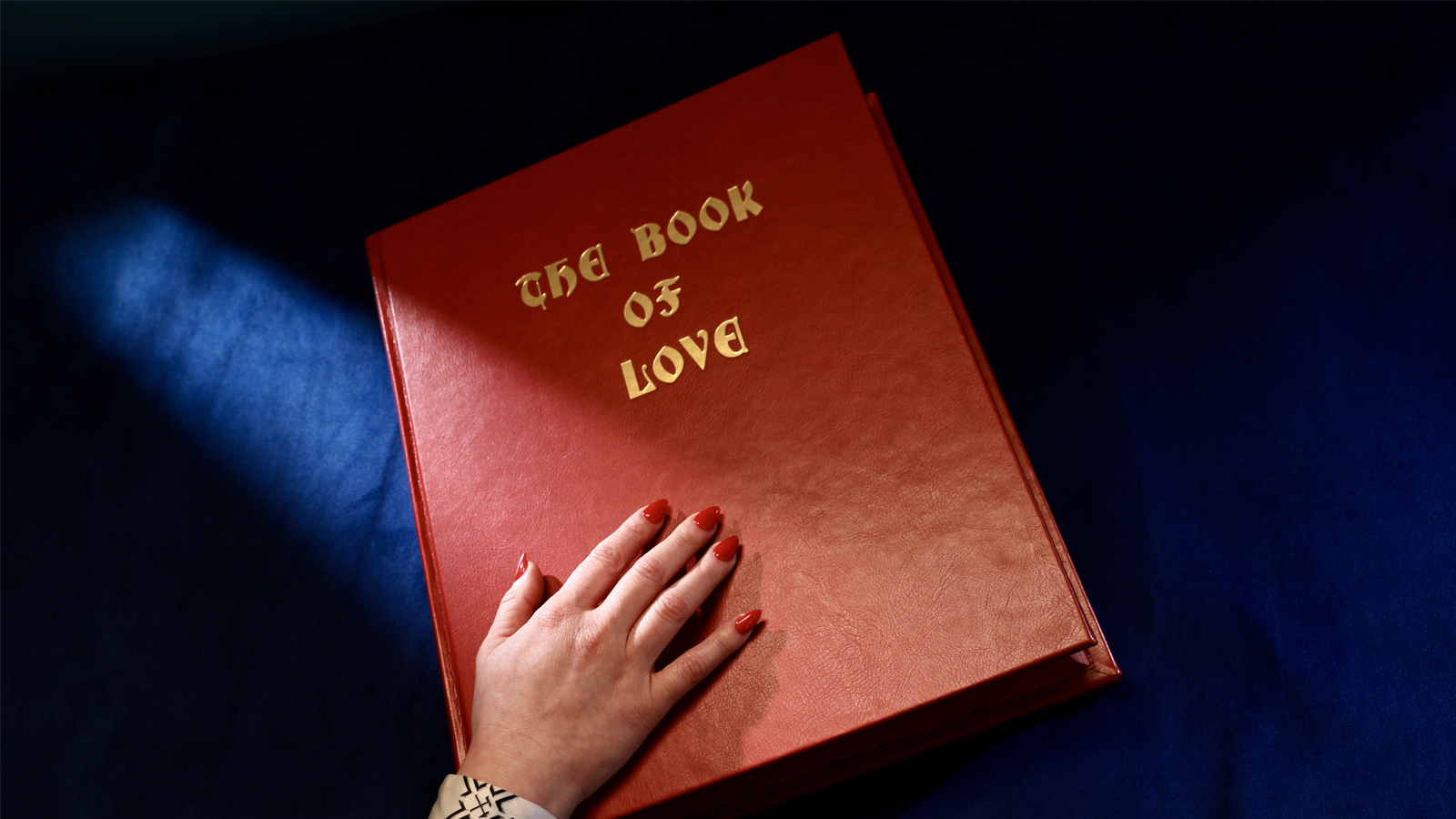

I feel that really happened to me around 2013 or 2014. I started working on this adaptation of Christine de Pizan’s ‘Book of the City of Ladies’, which would become a five year project called DC Productions, and suddenly there was an interest in it. With something that I had suppressed, there was a place for it to emerge in a much more powerful way than when I was trying to avoid it. There was an interest and discourse, and there were resources in terms of dialogue, and there was openness.

What is the place of film in your general work as an artist?

I was a fashion photographer. That’s how I made my money before and I was quite lucky that I started working, commercially, quite young. That’s why I stopped studying as well. While I was still studying photography I started working as a photographer and I felt like I didn’t need to continue that punishment for two more years.

Weirdly, the first show I did was not film. I was approached to be in an exhibition about the meeting point between fashion and art from the perspective of an arty fashion photographer. I felt that I didn’t want to do that, I wanted to do something else. So I made miniature collection of clothes and I put them in a glass box like a butterfly collection. And that was kind of the beginning.

I couldn’t draw well, I was actually horrified at my inability to draw or paint realistically, and maybe if I had gone to art school someone would have said “your style is really fun” or interesting or seductive, but in my mind I had these very conventional ideas of what it means to draw well, or what it means to sculpt well. And it was all around realism.

I struggled with what I could do technically and by doing these little clothes for that show I realised that actually there was this kind of new sculpture or this new world of installation, where you don’t have to do things realistically. So I had a solo show very quickly.

For that first solo show I did three videos and an installation, a few objects that were based on clothing as well and there were also these weird lights and giant dolls. It was like a world of possibility opened in front of me. People started seeing references and making connections with other works and artists and then this kind of (non-formal) education began for me, as opposed to the protected environment of a school. For me, the process of learning just happened in public.

I made these videos and then I moved to London in 2001 and I didn’t get a very big response from the rest of the work. But the videos, people loved them and I actually did manage to show them quite a lot. But then I didn’t continue doing that, I went in a very different direction. But film was always there, even though it’s not central anymore, it has always been there.

What is the origin of My Bodily Remains? How did it start?

I was in an extremely busy period and this wonderful organisation called Art Night approached me about an application for one of their projects. They were collaborating with the Museum of London, which is near Smithfield, the City of London and the Barbican, and the proposal was for something to do with the area.

So I put together a really wild application for a performance to be done in Smithfield, which now is a kind of meat market but, more relevantly, used to be the execution site in London. I then started thinking about it as a historical place of state violence.

Later, I was visiting my mom in Lisbon and we went to the Aljube Museum of Resistance and Freedom. We spent a long time there, it has lot of content and it really educated me. I knew about the basics, I knew about Salazar and the Carnation Revolution but I didn’t know about how that panned out on a somatic level and on the human scale.

That’s always something that is interesting to me when I think about politics, these two converging but very disparate scales – the political scale, of duration through an extended time, and the personal one, which is short. What that creates in terms of people’s expectations and level of commitment, during their lifetime, has always been quite interesting to me.

So when I went to that museum, one of the things that really left a mark on me were the Communist newspapers that were printed underground during the dictatorship in Portugal. I saw that there is such a history of huge life costing attempts to create global solidarity and build a much better world. And these attempts are always viciously suppressed. Like what’s happening now around the suppression of criticism of Israel during the genocide.

There is a history of all of these kind of tools being put at the surface to suppress leftist movements. So I was very impressed by the organising around the revolution in Portugal and the way it is memorialised also felt very beautiful to me.

I knew I wanted to include in this project historical figures and groups that were involved in direct action. I knew quite a lot about countercultural groups like the Weatherman and the Chicago Seven, about that era and just before, but I didn’t know how far back I could trace it. So I watched ‘No Gods, No Masters: A History of Anarchism’ and I was blown away by it.

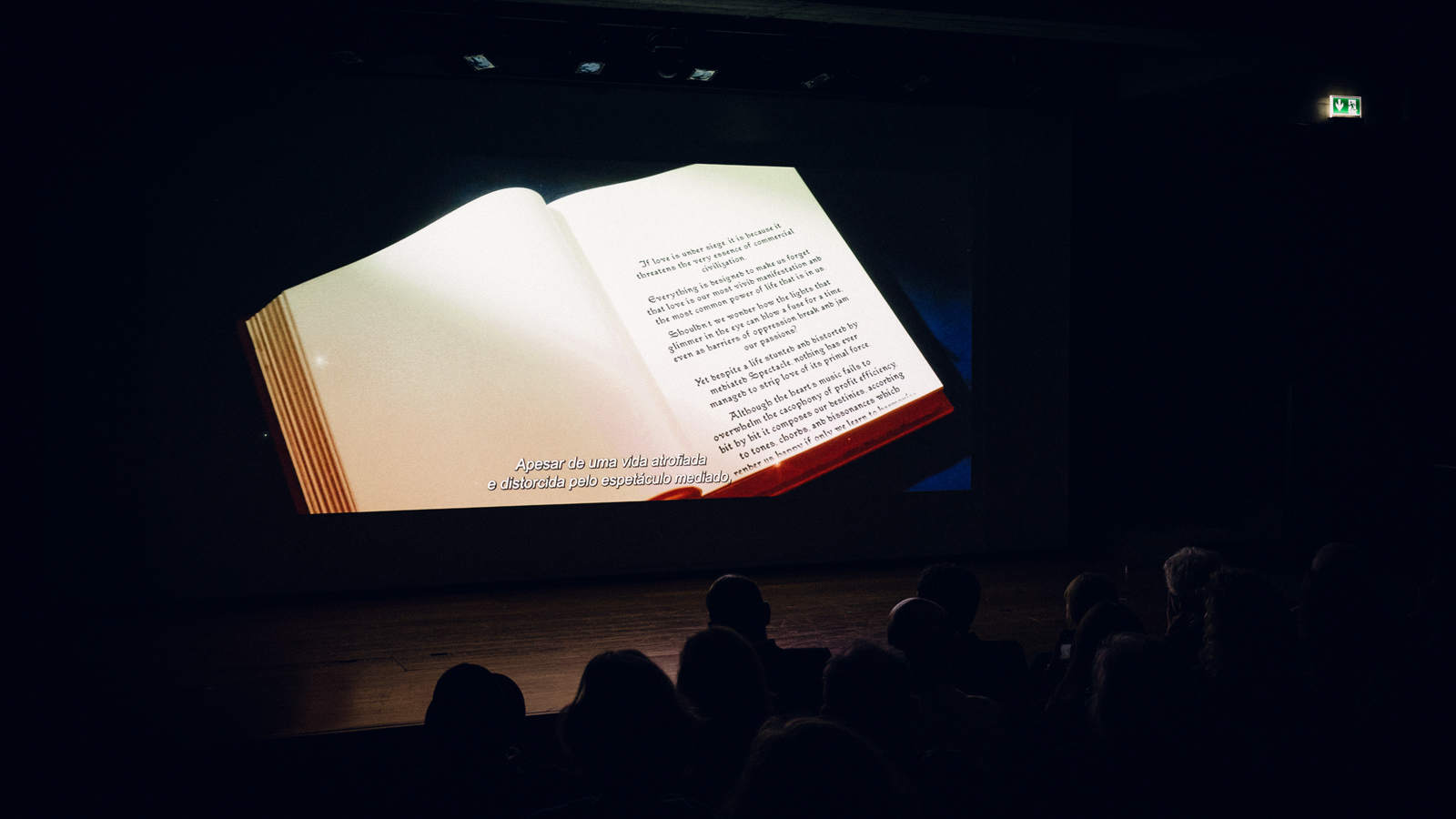

Reading passages by people that were involved in these movements you feel like that could have been written today, it could be about today. About equality, political equality, gender equality, wage abolition, all the kind of things that I still feel are the same demands of radical politics today.

The left is meant to feel like every day we start a new and that we start from zero without a history, a culture and a network of solidarity, but actually we stand on the shoulders of giants that came before us.

Can you talk a bit about the poetic and the political in this work? About your vision on using poetic language – and the transcendent, the sensorial, the uncanny – to talk about politics and to express your very clear point of view on culture and society.

I did that DC Production project, which was set in a post patriarchal city of women, and a lot of science fiction uses a kind of speculative scenario or world within which a kind of ideal politics can play out. I think that has always been a tool for politics, the use of a speculative scenario to explore the potential of radical politics.

Then I realised – and this isn’t a value judgement – that there’s always been this rift between a more analytical Marxist social realist position and a more fantastical dream world politics of a future. I guess one is very much an act of the imagination and the other one is about finding a blueprint of what needs to change now to get there. I think they both have a place but I really wanted to find a way to bridge between the two.

I don’t want to make a documentary or a film about what is happening right now or the world right now in its visual form. I want to talk about it but I wanted to maintain this kind of language that is elsewhere because that’s what I’m interested in, in terms of the effect of it.

One thing that I took away from that DC project was that there’s something about the ‘epic’ that has been co-opted by reactionary politics of the last 100 years of cultural production and I wanted to reclaim that in my work as a kind of feminist perspective.

I felt, at the time, that the feminist art that I was familiar with was very centred on the body and the domestic, politics of the household and reproduction. I really wanted to claim something else for feminism in a way. It’s a big claim but that were my aim, to claim a different territory for feminism. That’s something that I still feel is relevant.

I’m obviously super inspired by so many people, like Anne Boyer. I remember a piece of writing where she says that she doesn’t want to read about someone just getting in a car and driving across the county that doesn’t take into account the whole network of political reality that creates that situation. This kind of awareness that makes you realise that everything – fabric, food, how we traverse society – is political on a molecular level. And that was something that I somehow wanted to bring into this film.

There’s a poet called Sean Bonney who’s quoted in the film. I remember reading his work and also Jackie Wang’s, who wrote ‘Ocean Feeling and Communist Affect’, and they both felt very spiritual to me.

As a secular person, who doesn’t believe in a kind of organised idea of what the divine or God could be, I did feel that the building of a world where we will never live in it’s a form of spirituality. Love is a form of spirituality, the love that takes you outside of yourself and that collectivises you and encourages you to think of the happiness of those who are yet to be born.

I’d also like to ask you about your inspirations for this film in terms of visual style.

As an artist, I draw a lot more of my visual language from cinema. I’m interested in intensity of experience, even in sculpture and painting, and somehow the groundwork behind things is often this effect of intensity, which cinema is very much like. I used to be an obsessive Argento fan when I was younger and I also liked people that are really problematic now, like Jodorowski. As a young person, seeing those films, they were like explosions in my mind.

I remember when I watched ‘Paris is Burning’ and it was like when you see something and it reorientates your whole imagination and politics. I had lots of experiences like that around film that completely changed how I see things. I think that If I was to make one contribution to art, I would really like to do films that look like wild pop videos, that are very visually seductive and rich, but have this other subtext that’s not about that at all.

A lot of things I also take from dreams. The car scene in the film was something I dreamt years ago. The drone shots in the forest are also based on a recurring nightmare I used to have as a child where I was floating above the forest and there was a man who wanted to harm me in the most violent way. He was running underneath me while I was floating above the forest and the apparatus that I was using to fly started malfunctioning and going down. The drone scene was very much about that sense of dread, but in a reversed way where there is this banished community of women that live outside of society and they encounter this device, this drone that is coming into this mediaeval world.

I have always been interested in this idea of how, let’s say, someone 3000 years ago would have perceived a phone or would have perceived a piece of technology. If there’s an image that really inspired that it’s those I saw of uncontacted tribes in the Amazon. They’re being filmed by a helicopter very low down and they’re throwing arrows and spears at it. It’s such a powerful image, the idea of an uncontacted tribe that is living in a completely different time to us but also with us.

Looking at that scene with the drone, I was wondering if you’re interested specifically in this tension between the organic and the technological.

Yes, definitely. There’s a really wonderful book called ‘Riddley Walker’ which is about a post-apocalyptic future, some kind of post nuclear disaster, where people live in an Iron Age way, but there are these relics that they find and even the language they speak is completely different, a weird dialect that has evolved from English. It it’s a really wonderful book.

When my mom moved to Lisbon I found in her stuff some things from school that I wrote, and there was an illustrated story about these archaeologists that go to Egypt and, in an undiscovered tomb, they find a VHS tape. They carbon date and it’s like 2800 years old, it’s something that a time traveller left by accident there.

These slippages in time and a completely analogue encounter with technology is super interesting to me. As soon as I could read, I was given science fiction to read so I’ve always had these ideas around slippages, tests and simulations where suddenly there’s something incongruous. I guess it also relates to trauma a little bit, how maybe the fabric of time folds upon itself from trauma and you revisit the past as well.

I wanted to ask you about the use of CGI. What do you feel it brought to the project and what would be different if you didn’t have access to it?

The film I made previous to this one was called ‘The Neon Hieroglyph’. It’s also an hour long and with the same actor, and it was made during the pandemic. That film is maybe 90% CGI and there’s something about its symbolic value in this moment, and that changes all the time. Like how in my child’s story it was a VHS that people found, the kind of symbolism of technology is very fast changing.

Also, in a way, the digital realm emancipates you from the financial aspect. I mean, when you watch beautiful films from the 40s and 50s where everything is in camera… for me it would have taken days or weeks to animate those pearls (in the film) falling from the sky. With CG we just do the balls, get the texture right, choose the level of gravity, etc. So that’s something that I really like about it.

Adam Sinclair, the person I work with, he explains to me how he does stuff and I find it really fascinating. I’ll be like “They’re bouncing a bit too quickly” and he’ll put the gravity less so they bounce more. It’s kind of a manipulation of the physical world, almost like Prometheus. It’s so wild.

My last question has to do with text. I know it’s really important to you and it’s also pivotal in the film. What’s your relationship with writing and how did you select and organise all the text in the film?

My relationship with writing is painful. It’s something I try and distance myself from very unsuccessfully. I really would like to not write anymore because it’s the place I struggle the most, it doesn’t come easy. Some people write drafts and drafts, but for me it comes out like a tiny little thing. And what falls on the page stays, nothing gets erased.

I don’t consider myself a writer but it’s the most important thing in the work for sure, in a weird way. Even when I do object making, that first idea for a sculpture or an installation will often come out of the text and then it’s like a translation of an atmosphere in the text, or an idea.

I used to do a lot of performance, that was my main practice for years, and that’s a really seamless and very powerful way of delivering text. Someone reading, saying something, where everyone has to be quiet and look. This film was a play as well and that also helped organise the text.

I just wrote the text and then I attributed parts of it to different characters, so the form of a chamber play was overlaid on top of the writing and then the division of the text also happened in that way. I knew I wanted to quote, but I had to decide if the quotes were something that someone says and how to differentiate the characters.

So text is always really fundamental, but in a way it’s also where a lot of the problems happen, both in terms of my thinking and the focus and articulation of really complex ideas.

And also the relationship that it has with the rest of the work can be difficult as well, especially if you work in a commercial field, which I also do. These objects or paintings they become divorced from the whole completely. But often even the most commercial object I make at some point was linked to the text. It would be a great, great, great, great grandchild of an object that came out of the text.